|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Cochrane Ranch

by William Naftel

Foundation

Incorporation

On May 1881 the Cochrane Ranche Company was incorporated by Letters

Patent

for the purpose of the breeding and rearing of cattle, horses,

mules, sheep and swine in the Northwest Territories, dealing and trading

in them or any of them, throughout the Dominion; and of shipping the

same to foreign countries and of acquiring and holding the property

required therefore.1

The company was capitalized at $500,000 divided into 5,000 shares of

$100 each. At incorporation $270,000 worth of stock had been subscribed

of which ten per cent was paid up. The ownership of the shares was

divided as follows: Senator Cochrane, 1,000 shares; McEachran 1,000

shares; James Cochrane, 500 shares; James Walker, 100 shares and J. M.

Browning, 100 shares.2

Reaching this stage had meant a busy winter for Cochrane and his

associates, particularly McEachran who was taking a leading part in the

affairs of the company. First there was the organization of the company,

which meant setting up arrangements for the on-site facilities and

haggling with the Department of the Interior over the terms of the

lease. In February, leaving the winding up of these matters to

McEachran, Cochrane left for England to purchase the purebred

stock.3

The Cochrane Lease

The first recorded approach the senator made to obtain a grazing

lease was a letter written to J. S. Dennis, deputy minister of the

Interior, dated 26 November 1880.4 In it Cochrane expressed

his hope that, in view of the number of applications for leases, he

would be favoured in the selection of lands in the Bow River district.

It is evident from the general tone that Cochrane and Dennis had

discussed the matter previously. This was followed on 17 December by a

letter to Sir John A. Macdonald which evidently constituted a more

formal application. Accompanied by maps, the letter outlined in some

detail the plans for stock raising in the Northwest, plans which,

amplified and modified by a further letter of 10 February, constituted

an impressive package. The entire proposal involved an investment of

half a million dollars in breeding horses, sheep and cattle. The stated

objects of the company were to replace the American outfits which to

date had supplied the Canadian government's beef requirements in the

Northwest; to enable incoming settlers to purchase stock at a

reasonable price, and to build up a profitable overseas export

trade.5

So far as the arrangements respecting the lease were concerned,

Macdonald himself had said that the enterprise would receive "every

legitimate encouragement" from the government6 and Cochrane

was just the man to wring every possible scrap of meaning from that

statement. The continual pressure that Cochrane exerted over the next

few months ensured that the general outline of the ranching regulations

would be attractive to large-scale corporate investors; however, he

failed to obtain many of the details he suggested since many of his

"requirements" were too opposed to the public interest, even for a

favourably disposed administration.

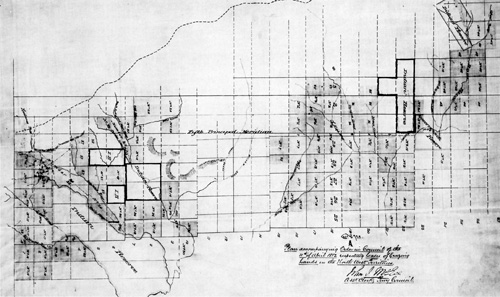

10 Map of the northern and southern ranges

of the Cochrane ranch, April 1882.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Cochrane made it clear that he expected the government to exert

itself to accommodate his needs. He agreed to the government proposal

that the term of the lease for the grazing lands be 21 years, but

suggested that the government should have the option of resuming the land

and cancelling the lease only after 7 or 14 years, if required for

agricultural purposes, and then by giving 3 years' notice. He further

suggested that if such cancellation were considered necessary, the

leased land ought not to be sold in areas of less than a township, with

the lessees having the option of purchase under the same conditions as

the settlers. Further, the lessees should have the right to select and

purchase up to 5,000 acres of the leased land at $1.00 per acre at any

time during the first two years. Cattle, horses and other stock would

be admitted free of duty in 1881 and 1882, along with farm implements,

wagons, harness, and so on required for the purpose of

ranching.7

Cochrane proposed generous terms for himself and it is a measure of

his brand of self-confidence that he would even suggest such a lease. It

is scarcely surprising that, with the exception of the proposal to admit

stocker cattle free of duty, the actual lease, the terms of which were

generous enough, bears only a general resemblance to this proposal.

The objections of the investors relative to the government lease, as

put forward by McEachran during Cochrane's absence in England, were not

unreasonable from a strictly ranching point of view, but with its

visions of settlement in the future the Department of the Interior was

not willing to shift its position much. McEachran noted that the option

to cancel the lease after two years meant that despite the enormous

investment required, what they were getting was a two-year lease,

renewable every two years for a like period. It would, he claimed, be at

least five years before any return on investment could be expected and

if the lease were cancelled after, for example, six years, ruin would

surely follow. Even if it were only cancelled in part, a latecoming

lessee or settler could in those pre-barbed wire days turn his cattle

among the new, improved and acclimatized herd and reap the benefits of

interbreeding free of risk and expense. A much more attractive

proposition in the eyes of the businessmen behind the Cochrane Ranche

Company would have been an uninterrupted 21-year lease with the right to

purchase in whole or in part on its expiration.8 These

objections were too radical for a department whose main commitment was

settling families on homesteads, but the form of the lease which was

approved (but not until March 1882) did resemble the Cochrane proposals

in its provisions for large-scale operations.

There was one point of conflict in the leasing provisions over which

Cochrane was reluctant to admit defeat. This involved the right to buy

outright a substantial acreage within the limits of the lease for use as

a "home farm." The first attempt to persuade the government of the need

for this concession was made in his letter of 17 December 1880 and he

elaborated further in his letter of 10 February when he asked to be

assured of the sale of a tract of 10,000 acres within the lease. This

was rejected by Macdonald, but in a memorandum drafted for council on 17

February the prime minister went so far as to accept the premise on

which the request was based — the need for a secure base of

freehold land from which to

operate — anticipating Dennis's recommendation of 9 May.

Macdonald was not, however, willing to admit that the ranch needed any more

security than 5,000 acres at $2.00 per acre.9 For some

reason, the memorandum embodying these views was never incorporated into

an order in council at this time, if indeed it were ever submitted.

Instead, a private agreement was reached at a meeting on or about 11 May

between Macdonald, Cochrane and Wiser. The agreement, substantially as

Macdonald had proposed but with the price of the land lowered to $1.25

per acre,10 was incorporated in the order in council of 20

May and applied to the entire ranching industry. On this order in

council, according to Cochrane's later statements, was based much of the

appeal to potential investors who were probably told that if the ranch

failed, the sale of the land would enable them to recoup their

investment.

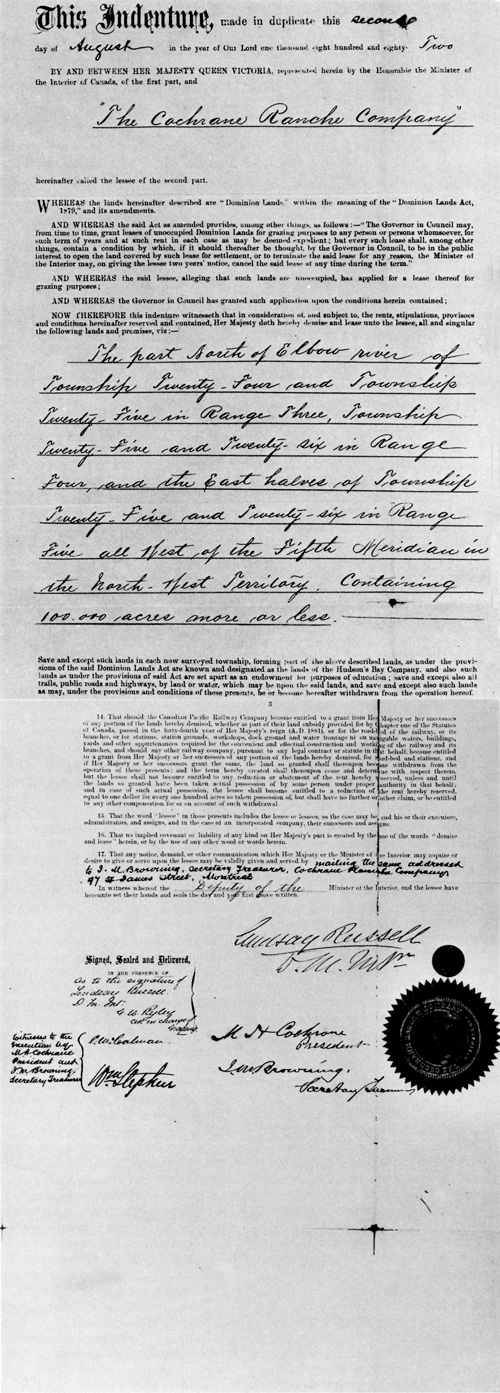

11 First and last pages of the lease for the Bow River acreage of

the Cochrane ranch, August 1882.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

In politics, however, nothing is certain and the order of 23 December

1881 revising the conditions under which grazing leases would be awarded

did no more than permit the lessee to "purchase land within his

leasehold for a home farm and corral."11 In other words, the

amount of land sold would be decided by the Department of the Interior.

Cochrane protested, but to no avail, for although he maintained that

only the 20 May 1881 order applied to him, the department stated that,

as his lease was signed in August 1882, the December order must prevail.

Some two years of letter writing and personal interviews availed him

nothing and eventually the Department of the Interior simply ignored his

letters on the subject.12 In the end, Cochrane received his

due, for the cancellation of the original leases announced in October

1892 permitted holders of those leases to buy up to ten per cent of

their leasehold the following spring at a price of $1.25 per acre.

Ironically, the price was established on the grounds that it was only

fair to sell at the amount announced in the initial set of regulations

of 20 May 1881.13

In other respects, however, his influence proved more potent. He was

able to persuade the government to entirely forbid sheep grazing on the

grounds that they would do extensive damage,14 and it was

only the personal intervention of the Marquis of Lorne that in the end

forestalled him. His Excellency pointed out that such a blanket

prohibition was a "most harsh measure . . . calculated to provoke great

dissatisfaction among the smaller graziers" and while he did not refuse

to sign the order in council (with the attendant constitutional

complications), he held it back, thereby preventing its publication

until he could persuade Macdonald to modify it by introducing a system

of ministerial permits for sheep grazing15 Nevertheless,

there was still bitterness; the "advice of a certain ranching senator"

was not well regarded by those who had taken out leases with the idea of

sheep ranching until forestalled by "this monstrous

restriction."16

In the matter of choosing the necessary grazing lands, the senator

was to demonstrate a remarkable capacity for getting his own way.

Certainly he left the departmental officials in no doubt as to their

relative positions in his scheme of things. "I have always understood

that I was to have first choice" he write, "I may, after personal

inspection, decide to locate in quite a different part from that which

you have assigned to me even approximately, and before I go into the

country I want authority to select where I choose, irrespective of any

applications made by others, provided I take it in a

block."17

The Ranch Manager

One of the most important aspects of organization was to locate a

suitable ranch manager. McEachran's official title was "Resident

General Manager," but his other interests were so extensive that it

would seem unlikely he ever intended to do much more than supply advice

when required. There is no evidence that he did more than that, though

this advice was, in the beginning at least, given priority. At any rate,

efforts were early made to locate a suitable ranch manager who could get

the new venture off on the right foot. Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney

had, in the course of his official duties, come to know Superintendent

James Walker of the North West Mounted Police well, and no doubt admired

the cool efficiency which marked the latter's performance of his

duties. For example, Walker had distributed over $100,000 among the

various Indian agencies of the territories during the summer of 1880,

facing a number of crises with restless Indians with the aplomb that was

becoming characteristic of the Mounted Police. Accordingly, in

conversation with Cochrane, Dewdney mentioned Walker as the ideal man to

manage the ranch and the senator took up the suggestion at once. Whether

by accident or design, Walker arrived in Ottawa late in 1880 as escort

to Mrs. Dalrymple Clarke, widow of an officer who died at Fort Walsh and

niece of Lady Macdonald. The proposal was put to him by Sir John A.

Macdonald. The annual salary offered was $2,400 compared to the $1,400

he received in the Mounted Police and Macdonald advised him to accept.

He did so in the new year, no doubt bearing in mind the favourable

impression he had received of the proposed ranch site on his previous

travels.18

The Cowboys

The cowboys employed on the Cochrane ranch were probably a rough lot

and many would have been American as a definite effort was made to hire

hands from the outfits that brought the drives up from the United

States.19 There was at least one exception as to nationality

on the Cochrane spread, the foreman Ca Sous, a Mexican half-breed who

was a fine cowboy, but had an abrasive personality that made it

difficult for him to get along with the men. Yet despite the cowboys'

backgrounds in the American West, it is almost a truism that the history

of the Canadian West was one of peaceful development. Perhaps when

McEachran sighed with relief on crossing the border on the way to

Calgary from Fort Benton and when he claimed that there was a

perceptible difference as soon as they reached British territory, it was

more than chauvinism.20

Whatever their nationality, the cowboys impressed the correspondent

of the Toronto Globe on his western tour in 1882.

Speaking of cow-boys reminds me of a duty I owe to that

much-abused class, and that is to say to the world that they are as a

rule grossly misrepresented. They are not as far as my observation goes,

anything like the terrible desperadoes they are generally supposed to

be. True, they usually carry long-barrelled six-shooters about them; but

if the mildest-mannered philanthropist that ever came out of the New

England States were called upon to mix himself up in the society of wild

Texas steers to the extent that they are I think he, too, would hardly

consider himself dressed till he had buckled on his cartridge belt and

his "hints to the onconverted." They are the very reverse of quarrelsome,

and on the other hand generous, good-hearted, and remarkably polite and

well-behaved towards strangers.21

The perquisites of a cowboy's existence seem to have been not too

unpleasant if F.W.G. Haultain's description is at all realistic. In the

early summer of 1885 he visited Cochrane's son William, who was managing

the operation on the southern range, and Haultain described to his

mother what he observed from the visitor's viewpoint:

Life on a ranche is not very eventful. One day I drove up with

Cochrane to the upper part of the range some fifteen miles from the

ranche buildings. It was a very pleasant drive over the prairie in the

direction of the mountains.... Ranche hours are, breakfast at 4:30 !!!!

dinner at twelve and supper at six, I find them not unpleasant now as

I go to bed at half past eight or nine. They feed very well here, having

plenty of milk and cream, and always fresh meat, which strange to say

are rarely to be found on a cattle ranche. The usual breakfast is

porridge and cream, beefsteak or bacon, potatoes, Canned tomatoes or

corn, beans, pancakes and maple syrup. Dinner is very much the same,

with the exception of porridge and pancakes, but with pudding or pastry.

Supper is the same as dinner. Very luxuriously, you will say, the

cattlemen live well, not exactly luxuriously, but well. Canned stuff is

a staple article all over the west and is used in great quantities. The

cowboys have large wages and hard work, and always require the best of

everything. Everything they have is good. Their clothes though rough and

suited to the country are good and they buy the very best underclothing,

socks, boots, etc.22

Round-up was the most difficult time for the cowboys, for the hours

were long and the work was fast and hard. Morning came early for a

round-up crew, already ten miles from camp when the sun rose.

Compensation was the early supper hour of 4:00 P.M., a consequence of

the cattle needing some time to graze and settle in before they would

bed down in new surroundings. In wet weather life was miserable.

Everything down to matches and to bacco was wet and soggy, horses were

mean and food was cold.23 Yet it was a free, open and

independent life out in the western air and far from teeming humanity.

As a way of life it drew many converts from the East along with those

brought up to it.

The Breeding Stock

The results of Cochrane's visit to England in February to acquire

pure bred stock for the ranch must have reassured the government if ever

it had any doubts as to the bona fides of the scheme. On 12 April 1881

the Dominion Line steamer Texas arrived at Halifax with what was

termed the largest consignment of purebred cattle ever imported into

Canada.24 The shipment raised eyebrows even in England and

the journal The Colonies and India noted,

Canada is determined to make the most of her opportunities for

improving her breed of cattle . . . last week saw one of the most

valuable consignments of live stock ever exported from this country

leave the Mersey for Canada, to be added to the stock of the Hon. M. H.

Cochrane, of Hillhurst, Quebec. Sixty odd Hereford bulls, including one

from Windsor, 45 polled Aberdeens [Angus], 6 Bates shorthorns, a dozen

Jersey and Guernsey cattle, was a fine cargo for one vessel and for one

owner. Besides these over 200 Shropshire and Oxford Down sheep and ten

Clydesdale stallions, all for the same owner.25

The bulk of the shipment, under McEachran's charge, was destined for

the ranch although at least 75 sheep went to Hillhurst.

Nor was this shipment the only one of its kind during the year. In

late October James Cochrane sent to Canada 86 Hereford bulls which he

had selected with some care from the herds of such celebrated breeders

as Lord Polworth and the Earl of Latham.26

These aristocratic animals represented only a fraction of the

proposed total herd, although upon their blood lines depended the

success or failure of the venture. Over the next few years these bulls

would mingle with some 8,000 range cattle and over that period would,

through their offspring, gradually raise the quality of the entire herd.

These thousands of range cattle would naturally come from the nearest

and cheapest source, the western United States.

Choosing the Ground

By the end of May 1881 the Cochrane Ranche Company had not yet

finally decided on a specific location for its operations, although

Cochrane made it clear enough that he wanted it in the Bow River

district which he may have visited the previous summer. At the beginning

of June, in company with McEachran, the senator set out for Calgary to

look over the ground and determine the limits of the lease. Despite a

provision in the regulations of 20 May requiring that the leases be

auctioned off, this was not to stand in the way of the Cochrane ranch;

the deputy minister of the Interior had on 9 May already presented a

report to the minister containing the names of those to whom promises of

grazing leaseholds had been made.27 One of these, of course,

was Cochrane. On the strength of this report which, while confidential,

Cochrane must have seen, operations went ahead as though the lease had

been granted, though it was to be a year before this was an accomplished

fact.

12 Cochrane, Alberta, 1964. The

ranch buildings are circled.

(Department of Energy, Mines and

Resources.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

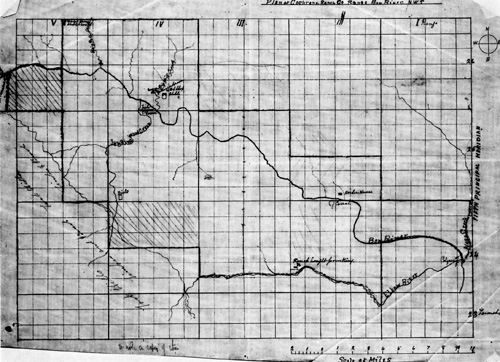

13 Map of Cochrane range, spring 1882.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

At this stage in the development of the North-West Territories, it

was still necessary to go to Calgary via the United States by railway

and steamer to Fort Benton, Montana, then northward to Fort MacLeod and

Calgary via horse or bull train. The trip was a long one and by the time

the senator's patty reached Calgary, Walker had staked out the ranch

site at Big Hill, an aptly named location about 23 miles west of

Calgary. The location suitably impressed the directors.

The land is rolling, consisting of numerous grass hills, plateaux

and bottom lands, intersected here and there by streams of considerable

size issuing from never-failing springs. The water is clear and cool.

Every one of them, as well as Jumping Pond [pound] Creek and Bow

River, is full of trout, brook and salmon, which are most delicious to

eat. There is an abundance of pine and cotton-wood on Jumping Pond Creek

and the hillsides, besides numerous thickets of alder and willow

scattered here and there over the range, which afford excellent shelter

for stock in winter. The grasses are most luxuriant, especially what is

known as "bunch-grass," and wild vetch or pea-vine, and on the lower

levels, in damper soil, the blue-joint grass, which resembles the

English rye-grass, but grows stronger and higher. On some of the upland

meadows wild Timothy is also found. These grasses grow in many places

from one to two feet high, and cover the ground like a thick mat. . . . The

site selected for the ranch buildings is a beautiful one, a level

plateau covered with rich pasture, on the north bank of Bow River, about

forty feet above the level of the water. It commands an extensive view

of the range, and from here the snow capped peaks of the Rockies are

seen standing out in bold relief against the western horizon. The soil

is rich, and the long grass which covers it will make excellent hay, and

in a few years, probably, it will be fenced in and divided into

beautiful fields with sheds and corrals necessary for the segregation of the

different breeds of the male animals, and otherwise assume the features

of civilization.28

Walker had been sufficiently confident that his choice would be

approved to mark out the boundaries preparatory to its being surveyed.

Nor was he disappointed; the directors agreed to his selection and

based the formal application to the government (not made for nearly a

year) on his choice.

As has been noted, the Cochrane lease was not finally signed until

August 1882 (although the designation of 46 leases, including

Cochrane's, was made in March), by which time the Cochrane Ranche

Company had been in occupation of its site and in actual operation for

over a year. The months before the signing of the lease had been put to

good use not only on the site but also back East. There was more to

ranching than just obtaining a lease of one's own; it was necessary as

well to ensure that one's neighbours were the right kind of people. As

early as May 1881 Cochrane undertook to impress upon the Department of

the Interior that he would greatly prefer it if Wiser held the

neighbouring lease rather than any of the other applicants. Further, he

pointed out, it had always been his understanding "that I was to have

first choice and Mr. Wiser next."29

14 View of the Bow River west of Calgary, circa

1885-88.

(Glenbow-Alberta Institute.)

|

In view of Wiser's business and other interests, it is not surprising

that Cochrane was anxious to have him as a neighbour and it is possible

that there was some plan to combine operations into one large-scale

ranch. It is a measure of his stature in the business world that when

Wiser visited Ottawa at the end of April 1881 to look into the matter of

obtaining a lease, the visit and the reason for it were reported the

following day in financial pages of the Montreal press.30 His

actual connection with the Alberta ranching industry did not in fact

develop along the lines which these initial approaches indicated, but

the connection with the senator remained close. At some point it was

decided to expand this plan and out of it grew the Dominion Cattle

Company, incorporated 23 September 1882.31 As originally

stated, this company was intended to carry out

breeding, raising, buying and selling cattle, horses, sheep and

other stock, and the carrying on in all its branches of stock-raising at

or in the State of Texas and the Indian Territory and elsewhere in the

United States of America, and also in the Dominion of Canada,

particularly in the North West Territory, with a head office in the city

of Sherbrooke, in the province of Quebec.32

The applicants for the charter were, W. B. Ives, MP, of Sherbrooke;

Senator Cochrane; Senator Ogilvie; J. P. Wiser, MP; R. H. Pope, cattle

breeder, MP (1889-1904) and senator (1911-14), from Eaton Township,

Quebec; Hugh Ryan, Perth, Ontario; Harlow C. Wiser of Prescott, and

William Presser Herring of Emporia, Kansas. The authorized stock of the

company was $800,000 divided into 8,000 shares of $100

each.33 The actual Letters Patent of Incorporation differ

somewhat from the information given above in that references to the

American operations had to be dropped because the purposes for which

applicants might be incorporated could only be those to which the

legislative authority of Canada extended.34

The Setting

For the first year or so the ranch was one of the few white

settlements in a still empty land, otherwise broken only by the Indian

mission of the Reverends John and George McDougall at Morley and the

North-West Mounted Police post at Calgary. The latter place "then

consisted of four or five log huts, i.e., The Hudson Bay Store, I. G.

Baker's, the police pallisaded post and the police officer, Captain

Denny's house."35

Morley, named in honour of the Reverend Morley Punshon who served as

chairman of the Canadian Methodist Conference from 1867 to 1873, was

almost the larger of the two settlements. Established in

1873, it had by this time a church, a day school, a mission house, a

store, various stables and an Indian encampment.

15 Bull trains.

(C. M. MacInnes, In the Shadow of the Rockies

London: Rivingtons, 1930].)

|

Communication with the outside world was slow. Supplies were brought

in by the freight teams of I. G. Baker and Company of Montana which

hauled all merchandise north from Fort Benton and Fort MacLeod. The bull

trains were imposing when encountered on the prairie. As many as 15 yoke

of oxen made a team pulling three wagons (the lead, the swing and the

trail) and any number of teams made up a train. Each train was supplied

with a cook and a mess wagon. Their slowness was legendary. On one

occasion when Walker arrived at Fort MacLeod on his way to Calgary from

the East, he was told, on asking for his mail, that it had left two

weeks before on the bull train. Calgary being 102 miles north of

MacLeod, Walker headed north expecting to pick up his mail at his

destination. He learned his error 40 miles out from Calgary where he met

the train placidly crawling north. With good weather, the foreman told

him, they would make it to Calgary in ten days.36

Initially the future of Calgary was held in such little regard by the

authorities that Fred White, comptroller of the Mounted Police in

Ottawa, initially tried to persuade Cochrane and Walker to take over the

police reserve, which covered much of the land in and around the

townsite, as a site for the ranch headquarters.37

Matters did improve, however, particularly with the announcement that

the CPR would take the southern route via the Kicking Horse and Rogers

passes rather than the northern route through the Yellowhead Pass. When

Frank White arrived in September 1882 to replace Walker as ranch

manager, there was a fairly bustling little community with a modest

social life. By 1883 there was sufficient population to support a

newspaper, the Calgary Herald, and with the arrival of the

railway in 1885 Fort Benton was displaced as the source of supply for

the Alberta district and Calgary became the distributing and shipping

point for the area.

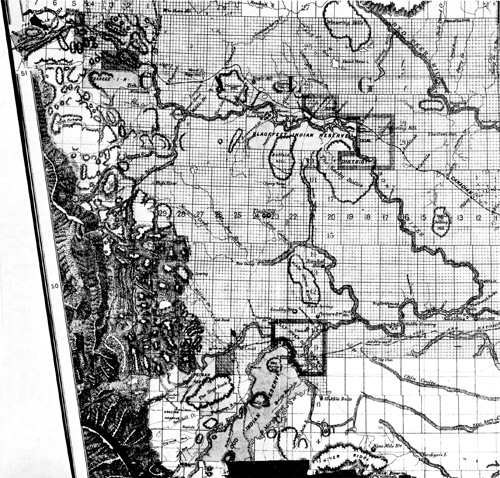

16 Map of leases, April 1887.

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The Indians were still one of the major problems which faced the

ranchers. Those tribes in the immediate vicinity of the Cochrane

operations were the Blackfoot, Blood and Piegan which formed one of the

most aggressive of the western Indian nations, the Blackfoot. In 1882

Commissioner Irvine worried about the effect of the incoming whites on

these people.

These Indians are entirely unused to large bodies of white men,

and know nothing of a railway or its use. The Indian mind being very

easily influenced, and very suspicious, it may be that they will

consider their rights encroached upon, and their country about to be

taken from them.38

While Irvine's report was perhaps a bit out of date, the problem was

still serious and initially the directors of the Cochrane ranch were

not unsympathetic. McEachran observed that

The large increase of white settlers, many of them frontiersmen

from the States or the other side of the mountains — men who

will not hesitate to shoot any Indian whom they may detect in, or even

suspect of, cattle stealing, together with the introduction of large

bands of cattle into different parts of the territory, greatly

increases the danger. It must be expected that these poor Indian people,

unless fed regularly and well by the Government, will, in their

semi-starving condition, find it very hard to refrain from killing

cattle. Unless the greatest precautions are taken to prevent a

disruption between them and the whites, they may be converted from a

most peaceful to a dangerous race, among whom neither life nor property

will be safe.39

This sympathy was to become somewhat dulled in future years as the

Indians, restless either from boredom or hunger or seeking to enhance

their prestige among their fellows, continued stealing horses and

cattle. While the loss thus experienced was never particularly serious,

it was a constant annoyance and the methods used — starting

prairies fires to drive horses toward a reserve — often angered the

ranchers more than the theft itself.40 Furthermore, the

Indian was a highly visible target for a rancher's indignation in

contrast to the many acts of God which beset him but had to be suffered

without seeking recompense. Nevertheless the ranchers generally tended

to blame the Indian Department rather than its charges on the grounds

that had the government lived up to its responsibility to feed and

educate the Indian, there would have been much less of a problem.

Representative of those acts of God against which man and beast were

totally helpless were the insects which, during a wet June, July and

August, made life unbearable. Cattle and horses were driven frantic and

often bled and sometimes died from the bites of bulldog flies.

Mosquitoes breeding in the tall grasses and in the sloughs covered

animals so thickly that it was impossible to tell their colour.

Frequently horses fled upwind for long distances to escape the torment.

The only possible relief was a "smudge," of which every ranch and camp

had at least one. This consisted of an enclosure about six feet square

surrounded by a strong fence and in the centre a smouldering fire of

wood, sagebrush and sods. The smoke kept the insects away to some

extent and around the smudges the stock would crowd and jostle one

another to get the best effect. Men dressed in gauntlets and nets

suffered somewhat less except at mealtimes when they either starved or

ate in the smoke of the smudge.41

These, then, are some aspects of the environment in which the

Cochrane ranch was to operate and which the Montreal capitalists set out

with unbounded confidence to exploit.

|