|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Cochrane Ranch

by William Naftel

Sales and Services

Markets

According to the statements of Cochrane and his associates, the ranch

had not been expected to become a profit-making operation before five

years had passed; however, it was not intended either that it should be

completely unproductive. Part of the incentive to move into beef

marketing lay in the natural desire to have at least some income to

offset the necessarily large outflow of capital in the pioneer years.

There was also a desire to cull the herd of substandard cattle while it

was gradually being improved. Finally, it was important to establish a

presence in the market quickly in the fact of an already firm grip on

Canadian government contracts by I. G. Baker and Company of Fort Benton,

Montana.

The original market for beef had been provided by the North-West

Mounted Police and to this was shortly added the Indian who, with the

disappearance of the buffalo, became dependent on that treaty provision

under which the Indian Department undertook to feed its wards. Initially

these markets were supplied by Baker's who bought all the beef produced,

which was not much, and who paid a fair price ranging from $35 to $45

per head. (None of this beef was beef of particularly good quality, the

theory being that beef was beef and an Indian would not know the

difference between an old bull and a prime three-year-old.1)

I. G. Baker and Company paid in cash or in trade at their Calgary store,

then placed their own "Figure 3" brand on the animals and turned them

out on the open range until needed.

All this began to change with the establishment of the Cochrane ranch

in the vanguard of the ranchers. Undoubtedly the senator used his Ottawa

contacts to ensure that Baker's did not long remain the sole supplier of

beef. Nor would it be surprising if the government were in fact anxious

to develop an alternative and Canadian source of supply.

No time was wasted in getting the first contract. Despite the losses

of the first winter and the effect it must have had on the availability

of the stock, a contract was signed with the Mounted Police at Calgary

to supply 64,000 pounds of beef for one year from 1 July 1882 at 8-3/4

cents per pound.2 The price was for beef on the hoof and for

the beef only; the hides, heads and feet were sold separately to

Baker's.

Another contract was signed for the supply of the Indians which, from

the government's point of view made quite clear the benefits of

competition. Where Baker's charged 9-1/4 cents per pound to supply the

Indian Reserve at Blackfoot Crossing, Cochrane charged 7-3/8 cents; at

the Sarcee Reserve, Baker's got 8-3/4 cents, Cochrane 7-1/8 cents, and

at the Morley Reserve, Baker's charged 9-1/4 cents and Cochrane 7-3/8

cents.3

With the advent of the CPR, a new market was opened up for the supply

of the construction gangs. The appetite of the workers was such that

many Alberta ranchers received their starts from sizeable CPR beef

contracts. This did not last beyond the driving of the last spike, but

the opening of the railway established new avenues of exploitation. In

the first place, the arrival of settlers increased the local market

which had formerly played a minor part; secondly, it opened the entire

Atlantic community to the Alberta ranches. This second point was the

cornerstone on which ranches on such a vast scale had been established,

but there was some delay in taking full advantage of it after the

railway went through for the bitter winter of 1886-87 had a bad

effect on the availability of steers. A sharp drop in prices, however,

forced the cattlemen to look about for an expanded market. In late 1887,

700 head were exported to Britain as an experiment and after paying all

expenses the shippers realized $45 per head. This was the beginning of a

substantial export trade which proved to be profitable for those

ranchers who were willing to make the effort to meet the high standards

demanded by British buyers and had the instinct to judge the sometimes

capricious shifts of the international cattle trade. On the other hand,

underbred and underfinished cattle always resulted in a loss to the

shipper and the arrival of a consignment at the wrong time of year or

when the market was glutted could again mean heavy losses.

Shipment of live cattle was a problem in the first years. During the

long journey from Calgary or Medicine Hat to Liverpool or Southhampton,

an animal which had started out a fine specimen of beef on the hoof was

likely to arrive at its destination bruised, battered and worried out of

hundreds of pounds. Though in the early days the CPR's equipment for

shipping stock was minimal, they did their best and the cattle were

rushed through as fast as possible. Live shipment nevertheless remained

necessary as refrigerators cars were still a thing of the future and

consequently speed and a minimum of handling were important to ensure

that the animals lost as little weight as possible. McEachran was saying

as late as 1907 (at hearings of the Alberta Beef Commission) that while

refrigeration would increase the value of beef cattle from 25 to 30 per

cent, the difficulties in the way were almost

insurmountable.4

Local prices were good, the Calgary market ranging between 6-1/2 and

9 cents per pound and in the early days (ca. 1882) reaching as much as

10 cents per pound.5 Baker continued to offer good prices, as

high as $32 for two-year-olds and $40 for three-year-olds. Chicago

prices held fairly steady between 5 and 6 cents and Montreal between 4

and 5 cents.6

The marketing situation remained fluid during the tenure of the

Cochrane interests at Big Hill and, like many of the pioneer ranchers, the

senator seems to have acted as his own sales agent. Smaller ranches,

however, did not have the resources to establish markets on the eastern

seaboard and overseas, and livestock agents were beginning to dominate

the business of cattle marketing by the 1890s. One of the first was the

ubiquitous I. G. Baker and Company which filled this function in the

earliest years and they were succeeded by Patrick Burns, J. H. Wallace,

Gordon and Ironsides, and J. D. McGregor, among the better known.

The advent of the Cochrane and other ranches meant a change of a sort

for westerners. Before the ranches, beef was just as likely to come from

one of the cast-off ox teams of a bull train. Henceforth the grass-fed

steer would reign and to those most concerned it must have been a

pleasant change indeed.

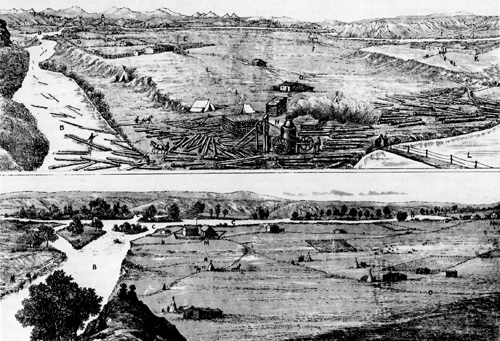

20 Calgary Bottom, 1862, looking west (upper) and north (lower) from

Frazer's Hill by General Thomas Bland Strange. A, Catholic mission;

B, Elbow River; C, Bow River; D, restaurant;

E, I. G. Baker & Co, store; F, old church; G,

Cochrane ranch butcher shop; H, Cochrane ranch steam sawmill; I,

Fogg's ferry; J, Frazer's Hill; K, N-WMP fort; L,

boom bridge; M, HBC store; N, Captain Denny's House,

O road to Fort MacLeod.

(Canadian Illustrated News,

Vol. 26, No. 27, [30 Dec. 1882], p. 421.)

|

The Subsidiaries

As the first major commercial enterprise (apart from I. G. Baker and

Company) with any amount of capital in the Calgary area, the Cochrane

ranch moved to fill part of the vacuum caused by the lack of services

in a developing area. Surprisingly enough, considering the

merchant background of so many of the interested parties and the

evident future of the town, no attempt was made to exploit or pursue these

initial ventures and they shortly disappeared.

The most obvious of these was a butcher shop which served as a retail

outfit for the sale of beef to the citizens of Calgary. This enterprise

was started at the beginning of ranching operations, probably as a means

of bringing in some cash, though with the almost continuous shortage of

cattle resulting from the failure of the herds to winter well, it must

have strained the corporate resources at times to keep the shop properly

supplied. Evidently it was very much a secondary operation as far as

Walker was concerned and when White arrived he found the accounts in

confusion and had to spend some time in straightening them out. White

seems to have considered the retail operations an important part of the

business inasmuch as he altered plans for a new company building under

construction in Calgary to include a new butcher shop.7

Steers for the shop were kept at a camp at Nose Creek and this, plus the

Calgary Mounted Police contract, took about 20 head a month.8

The Indian Department paid just over 7 cents per pound for its beef, the

Mounted Police paid 8-3/4 cents and the patrons of the butcher shop paid

10 cents per pound.9 Just how long the butcher shop continued

in operation has not been determined. It would seem unlikely that it

survived the transfer of the cattle operations to the southern

range.

The other aspect of the company's operations, the sawmill, showed a

good deal of foresight in view of Calgary's future. The mill was erected

early in 1882 at the instigation of Walker who, since it was too far

from the ranch to be of much use there, must have foreseen the need for

such an operation with the construction of the CPR and the prospect of

settlement. A small steam sawmill was brought out, a manager, Mr.

Gilmour, appointed, and a timber concession obtained from the Department

of the Interior. Walker's business sense was apparent on his requesting

at his resignation that in return for his equity in the company, the

sawmill be turned over to him. This was done at a mutually agreed upon

valuation of $15,000.10 In a remarkably short time Walker had

a contract for 750,000 ties for the CPR, was supplying lumber for

Cochrane ranch buildings, and over the next few years supplied much of

the timber for the early trestles erected by the CPR.

|