|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 7

Archaeological Explorations at Signal Hill, Newfoundland, 1965-1966

by Edward B. Jelks

Queen's Battery Area

Most of the 1965 field season was spent excavating the Queen's Battery

and its immediate environs. Two subareas were distinguished: (1) a lower

level where the guns had been mounted; and (2) an upper level just to

the north where magazines and other structures once stood.

10 Archaeological base map of the Queen's Battery area.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Lower Queen's Battery

The battery proper was situated on a sort of shelf, some 160 ft. long by

40 ft. wide, overlooking the Narrows of St. John's harbour from atop a

particularly precipitous section of cliff (Figs. 11, 12). This shelf,

referred to here as the "lower Queen's Battery" area, was excavated by a

crew under the supervision of Carole Yawney. A stone building foundation

(structure 3) and three paved areas (structures 5, 6, and 7) were found

there.

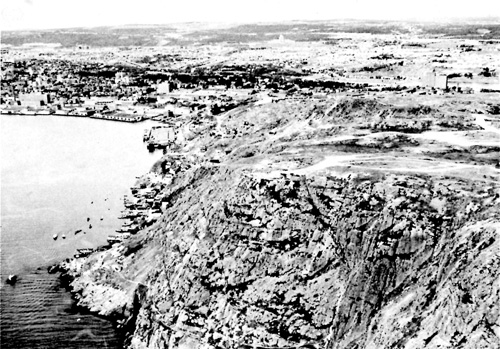

11 Aerial photograph of cliff at north side of the Narrows with Queen's

Battery area at its top.

|

12 Lower Queen's Battery area after excavation, view looking

east-northeast (taken with wide-angle lens). Note stone foundation of

structure 3, low scarp at left, parapet at outer edge of battery, iron

traverse tracks mounted on stone bases, Cabot Tower in background.

|

Along the shelf's outer edge was a low stone parapet behind which

stood, in 1965, a battery of six cannon mounted on wooden bases. The

cannon were not original, having been brought into the park from some

unknown source—probably after 1900—and set up to portray, for

the benefit of park visitors, how the battery might have looked early in

the 19th century.

Across the back of the lower Queen's Battery area, that is, along the

inland edge of the shelf, the bedrock rose to form a narrow ridge

running roughly east and west and parallel to the cliff at the seaward

edge of the battery. The top of this ridge stood some 12 ft. above the

level of the lower area of the battery, and its south flank, facing the

gun emplacements, formed a steep scarp. The stone parapet along the

outside of the shelf curved to meet the scarp at both ends of the lower

Queen's Battery area. The face of the scarp had been scaled off to make

it steeper along much of its western half and also at its extreme

eastern end.

Prior to excavation an earthen ramp angling up across the middle of

the scarp provided a connecting roadway between the lower level of the

battery and the upper level behind the scarp. East of the ramp where the

scarp made a concave bend there was a stone retaining wall running along

the chord of the bend, and the space between the wall and the scarp was

filled with earth. The retaining wall, in effect, extended the

approximately straight-line face formed by the western half of the scarp on

across the eastern half. The retaining wall ran underneath the east side

of the earthen ramp but did not emerge from the west side. From

superficial appearances it looked as though the ramp was built at a

later date than the retaining wall, and this was borne out by

excavation.

The lower area at the Queen's Battery was thoroughly explored.

Virtually all of the cultural deposits lying on the shelf behind the

parapet were excavated, and deposits banked against the exterior face of

the parapet were tested.

There was one major structure in the lower Queen's Battery; the stone

foundation of a rectangular building designated as structure 3. Other

structures, three patches of flagstone paving near the cannon, were

labelled structures 5, 6, and 7 respectively.

Stratigraphy

Study of the deposits in the lower Queen's Battery area revealed that

the flat shelf on which the battery had been installed was not a natural

topographic feature but a purposely levelled surface. Originally the

ground had sloped steeply from northwest to southeast, but it was

levelled with stone rubble before the battery was emplaced. In addition

to the rubble there were several other major depositional zones that

proved of importance to archaeological interpretation of the area (Fig.

13).

13 Composite photograph showing typical soil

profile at lower Queen's Battery. Note (from top to bottom) top soil

(zone A), thin layer of charcoal (zone B), brown soil (zone C), whitish

stratum containing crumbled mortar (zone D). The rubble zone (E) is not

exposed. Part of structure 3 is visible at lower left.

|

Zone A. Semisterile topsoil, averaging about a foot thick,

extended over all of the lower area of the Queen's Battery. The upper

part of this zone was a layer of turf that obviously had been laid down

in relatively recent times, as it extended over the gravel fill of the

trenches in which the traverse track foundations were set. According to

Patrick Brophy, custodian of Signal Hill Park in 1965, the area was

sodded during or shortly after World War II.

Zone B. A thin charcoal-stained zone, nowhere more than an

inch or two thick, appeared just beneath the topsoil over much of the

lower Queen's Battery area. It contained little cultural material.

Zone C. Semisterile brownish, sandy clay, generally between

one and two feet thick, was distributed over the entire lower area of

the Queen's Battery. This was apparently a layer of detritus that washed

down from the upper area of the battery to the northwest. It contained a

few bits of charcoal and an occasional tiny fragment of metal or a sherd

from a broken dish, but these were probably washed in with the

detritus.

Zone D. A zone in the general vicinity of structure 3 with a

high content of deteriorated mortar, up to 1.5 ft. thick, was rich in

artifacts. Resting directly on top of the stone rubble with which the

area was initially levelled, this zone consisted of trash that

accumulated in and around structure 3, presumably during the time it was

used as a barracks and perhaps for a short time afterward.

Zone E. The rubble used for levelling, distributed over the

southern and central portions of the lower battery area, reached a

maximum thickness near 7 ft. and was semisterile. The rubble consisted

of small, irregularly shaped stones from an inch or so to a foot or two

in diameter with an occasional brick intermixed. Some of the stones had

patches of mortar adhering to them, indicating that they had previously

been part of a building at some undetermined place. Since the original

ground surface had sloped downward to the southeast, the bed of rubble

was thickest along the edge of the area near the parapet, and it pinched

out against the higher ground on the north and west. Much of the

foundation of structure 3, the paved spots near the cannon (structures

5, 6, and 7), and the stone parapet were all laid directly on the

levelled surface of the rubble. The foundations for the traverse rails

had been set in trenches that were dug into the rubble zone and refilled

with small gravel.

Zone F. Sterile deposits of glacial till rested on the

irregular surface of the sandstone bedrock. The upper part, representing

the surface of the ground prior to levelling, showed light humus

staining produced by decayed vegetation. This zone actually included

several different lenses of varicoloured soils, grouped here in a single

zone for all of them are localized deposits of oxidized glacial till

and, more importantly in an archaeological study, all of them predated

human occupation of Signal Hill and were completely sterile of cultural

material.

As at the Interpretation Centre area, a fine-grained, grey clay

coated the buried surface of the bedrock. Patently this was a subsurface

accumulation formed by the redeposition of fine particles that were

transported downward by percolating ground water. Some of the buried

bedrock surfaces bore exceptionally well-preserved glacial polish and

striations (Fig. 5).

Structure 3

At the south end of the lower Queen's Battery area was found the stone

foundation of a long, narrow, rectangular building (Figs. 12, 14, 16) of

the proper dimensions to have been building 35 of the historical base

map (Fig. 4), a wooden barracks erected prior to 1812. Approximately 55

ft. long by 13 ft. wide with its long axis running east-northeast and

west-southwest, this building had been built against the previously

described bedrock scarp marking the western boundary of the lower

Queen's Battery shelf. The foundation consisted of undressed and crudely

dressed stones of variable size mortared into narrow rows only a foot or

so wide.

14 Structure 3, view looking east-northeast. Note partitioned room

with brick hearth in foreground, chimney base at upper centre.

|

15 Room at southwest end of structure 3. Note flagstone entry at

lower left; brick hearth at upper right.

|

16 Plan of structures 3, 5, 6 and 7.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

The south wall and adjacent parts of the east and west walls were

laid on and in the upper part of zone E, the stone rubble with which the

lower Queen's Battery area had been levelled. Because it was so crudely

made, the foundation was difficult to discern among the rubble at times.

It stood only one stone high in most places, but there were two and even

three tiers remaining in others, especially in the eastern portion of

the structure. The north wall must have been built directly against the

vertical face of the bedrock scarp which had, in fact, been partially

scaled off and dressed to make it straighter and more nearly vertical

where it bordered on structure 3. The foundation was not sturdy enough

to have supported masonry walls; therefore it appears certain that the

walls of the building were of wood.

A narrow cross wall marked off the building into two rooms, a large

one 45 ft. long by 13 ft. wide at the east end and a smaller one (Fig.

15) measuring 10 ft. by 13 ft. running across the west end. At the north

end of the smaller room was a brick hearth laid directly on the ground.

A large rectangular chimney base (Fig. 17) near the centre of the large

room was so placed as to suggest that its chimney was shared by two

back-to-back fireplaces, presumably serving separate rooms. However,

there was no evidence of a partition in the surviving foundation

pattern.

17 Chimney base, structure 3; view looking southwest.

|

18 Detail of stone foundation, east corner of structure 3; view

looking north.

|

In and around the foundation of structure 3, especially in the

eastern portion, were relatively heavy accumulations of trash in zone D,

much of which appeared to have been discarded by the occupants of the

barracks. These accumulations produced a large and varied sample of

artifacts.

Structures 5, 6, and 7

Structures 5. 6 and 7 were small floor areas paved with flagstones,

or with flagstones and brick mixed together. The floors were laid on top

of the stone rubble used to level the area and were buried beneath

several inches of topsoil. The trenches in which the traverse track

foundations were set had disrupted the floors, leaving only remnants of

what originally may have been rather extensive expanses of paving.

The purpose of these floors is not certain. Since they occupied the

gun emplacement area, perhaps they were to provide solid footing for the

men working the guns; or possibly some of them were floors of sentry

boxes like the one that reportedly stood in the lower Queen's Battery

area in 1805 (Ingram 1964: 28). Structure 6, especially, appeared to have

been of the proper size and shape for a sentry box floor.

Structure 5 (Figs. 16, 19) had been partially destroyed by a ditch in

which the traverse track foundations for one of the cannon had been set.

One edge of the pavement abutted the inside edge of the stone parapet,

but it could not be determined with certainty whether the pavement was

older or younger than the parapet.

19 Structure 5, view looking northeast.

|

The surviving portion of structure 5 occupied a curved area about

15ft. long and averaging perhaps 7 ft. or 8 ft. wide. The stones at the

inner side were arranged in a squared up pattern. The original shape of

the whole paved area is uncertain.

Structure 6 was a square paved area about 7 ft. across with a short

extension leading off the north corner (Figs. 16, 20). Paved with stones

and bricks, it was built up against the stone parapet that borders the

lower Queen's Battery. Most of the stones had been crudely squared to

make them about the same size as the bricks. There had been some

disruption of the pavement by two of the traverse track ditches. Traces

of mortar indicated that the stones and bricks had formerly been

mortared together.

20 Structure 8, view looking northeast. (Label in photograph shows

wrong structure number.)

|

Structure 7 (Figs. 16, 21) consisted of a roughly rectangular floor

paved with flat, unshaped stones of varying sizes. Located near the

northeast end of the lower Queen's Battery, it measured about 6 ft. long

by 5 ft. wide, There were no traces of mortar between the stones.

Although interrupted by traverse track ditches, the floor, when

complete, was probably little larger than the portion that has

survived.

21 Structure 7, view looking north.

|

22 Excavation outside parapet, lower Queen's Battery, showing parapet

foundation; view looking west.

|

Upper Queen's Battery

The upper level of the Queen's Battery area lay above, and to the

northwest of, the scarp that demarcated the border of the lower level

(Fig. 10). The upper level consisted of a narrow bedrock ridge running

along the top of the scarp, and behind the scarp to the northwest, an

elongated, shallow depression averaging about 30 ft. wide paralleling

the ridge. Another scarp, 10 ft. high on the average, bordered the

elongated depression on its northwest. The entire area was explored

thoroughly.

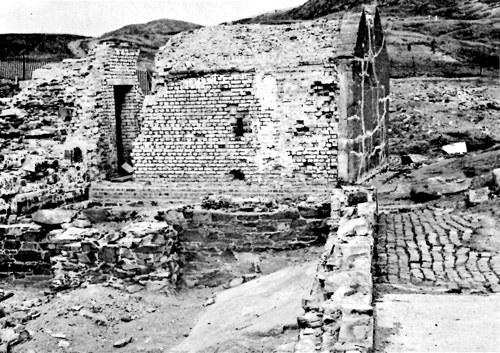

Several masonry structures in various stages of ruin and disrepair

were to be seen on the upper level before excavation began: (1) a

one-room brick building with an intact, vaulted ceiling connected by a

passageway to a one-room stone and brick building with its roof

collapsed; (2) the ruins of a building comprising two large rooms, and

(3) stone walls standing several feet high which connected the two-room

and one-room buildings. Since this whole complex of rooms was joined

together and the historical relationship of one room to another was not

clear at the beginning of excavation, the entire series of connected

rooms was labelled structure 2. Subsequently, excavation revealed that

structure 2 consisted of several distinct components (magazines,

barracks, and other structural elements of uncertain purpose), some of them

built at different times than others. In several places there was

unmistakable evidence of remodelling.

One other major structure, a rectangular foundation of stone, was

discovered in the course of excavating the upper Queen's Battery. It was

designated structure 4. Minor structural remains found in the vicinity

of structure 2 included remnants of several masonry walls and a

subterranean drainage system made of bricks and stones.

Stratigraphy

In the upper Queen's Battery area, bedrock was exposed on the

surface at the more elevated spots but was buried beneath deposits of

glacial till, detritus, and topsoil in lower places. The geologic

deposits were of no particular value for archaeological interpretation,

being relatively thin and containing no undisturbed archaeological

material. But within the component rooms of structure 2—and to a

lesser extent around structure 4—the deposits often consisted of

discrete strata containing cultural residue. These strata were

excavated separately wherever it was practical to do so. The details of

localized stratigraphy will be described below in the discussions of the

respective structures and rooms.

Structure 2

Structure 2 was the previously mentioned complex of rooms and walls

at the upper level of the Queen's Battery, much of which stood above

ground when excavation was begun in 1965. Buildings 52, 59, and possibly

80 of the historical base map were clearly present in the complex.

Prior to excavation, structure 2 was divided into five components,

labelled rooms A through E (Fig. 23), and each was dug as a unit. A

house (partly frame and partly brick according to informants) was built

over the ruins of rooms C, D, and E at some unknown but relatively

recent time, probably in the 1920s.

23 Plan of structures 2 and 4.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

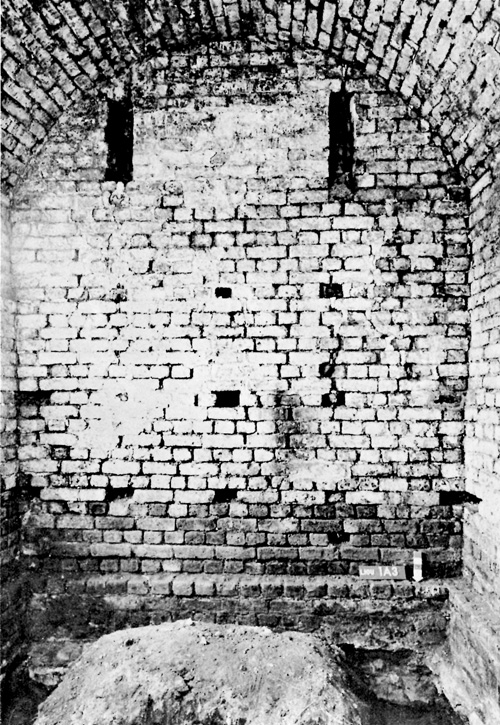

Room A. The most complete early building on Signal Hill, room

A was a brick magazine with a vaulted ceiling (Figs. 23, 26), evidently

either building 36 or 52 of the historical base map (Fig. 4). A major

portion of its brick roof was still in place in 1965; however, the

entire building was levelled in the winter of 1965-66 as it was deemed a

hazard to park visitors. Room B was razed at the same time.

24 East side and north end of room A, structure 2. Concrete reinforcing

has been applied to the south end in modern times. The windows were

added after the room was no longer used for storing powder.

|

25 View looking east down the south wall of room E (foreground) and D

(beyond brick cross wall at lower left); room A in background. Note the

steeply sloping bedrock inside room D; also the chimney base against

room D's east wall.

|

26 Interior of Room A, structure 2, showing the vaulted ceiling and

the south wall. The two vertical slits just below the ceiling are the

interior openings of a baffle-type ventilator.

|

Made of yellow brick laid in English bond, the magazine here

designated room A was a sturdily built structure. Its walls, more than 2

ft. thick, were supported by a brick footing some 3 ft. wide which

rested on a massive foundation of dressed and rough stone mortared

together. The latter was seated on bedrock or, in some places, on compact

glacial till.

Room A was of rectangular shape, with its long axis running roughly

north and south. The original floor was of wood. Baffle type ventilators

had been built into the east, west, and south walls, and a narrow hall

with an arched brick ceiling ran across the north end. The hall possibly

served as a shifting room. A door at its east end opened to the outside,

and entrance to the magazine proper was gained through a door in

the south wall of the hall. The exterior surface of the south wall had

been stabilized—rather obviously in recent years—by applying a

coating of concrete.

Inside dimensions of the main room were; length, 12.5 ft.; width,

8.25 ft.; maximum ceiling height above the original floor level, 9.5

ft. A subterranean drain made of brick ran around the exterior of the

magazine against the outside of the wall's footing, a foot or so

beneath the surface of the ground; it led off to the northwest, joined a

stone drain coming down from room B and continued to the western border

of the Queen's Battery area where it emptied down the hillside (Figs.

23, 27, 28, 29).

27 Detail of drain construction, south exterior wall foundation of

room A, structure 2.

|

28 Juncture of drains from room A (left) and room B (right).

North exterior wall of room C at upper left.

|

Room A had been remodelled at least once and probably twice. When

room B (another magazine) was erected contiguous to room A on the

north, a connecting doorway was cut through the north wall of the

narrow hall. Two windows were cut into the east wall of the main room

after it was no longer used for storing powder, and a door was

installed at the west end of the hall. Two rows of bricks running across

the room evidently had helped support a wooden floor during the later

occupation of the room.

A few artifacts were found in the soil inside room A, but no

stratigraphic analysis was attempted as most of the artifacts appeared

to be of very late 19th- and 20th-century age and of little or no value

for distributional analysis.

Room B. Another magazine, room B (Figs. 23, 29) was constructed

of stone after room A was already standing. It consisted of a

rectangular main room the same size as room A (12.5 ft. by 8.25 ft.

inside dimensions) and a hall (Fig. 30) connecting it to room A. The

long axes of both the room and the hall were aligned with that of room A

(that is, running approximately north-south). The north wall of room A

was incorporated into room B as its south wall, and a door was cut

through its centre to provide entrance into the main room via the

hall.

29 West side of room B, structure 2, view looking east. Part of room A

at upper right, curved drain at lower right centre, structure 4

foundation angling across photograph at lower left.

|

30 Looking north from inside room A, structure 2, down

granite-ceiled hall of room B. The collapsed ruins of

main room B are visible at the end of the hall.

|

Judging from pieces of granite lying nearby, the exterior of this

magazine above ground level was originally faced with slabs of granite,

but if so the facing was subsequently removed. The walls were estimated

to have been about 4 ft. thick when still intact, and, behind the

facing, they were made up of rough, flat, irregular stones set in

mortar. In 1965, the interior wall surfaces consisted of the flush edges

of these flat stones (Fig. 31), but before the magazine fell into ruin

they were probably surfaced with plaster.

31 North interior wall of room B, structure 2, after rubble has been

cleared out.

|

There had been a vaulted ceiling like that of room A (except that it was

made of stone), but it had collapsed along with the roof. Still in place

was the ceiling of the hall at room B, consisting of long blocks of

granite laid athwart the hall, their ends resting on the tops of the

east and west walls (Figs. 30, 32). The hall was floored with

flagstones; the main room originally had a wooden floor.

32 Detail of east wall, room B, structure 2, showing window and

granite-slab roof construction.

|

Two magazines (buildings 36 and 52) are shown in the upper Queen's

Battery area on the historical base map (Fig. 4), but they are portrayed

as being separate, not joined. Nevertheless, rooms A and B must be the

magazines shown. Unfortunately there is no available information on the

dates of construction or other historical details regarding them.

The south half of room B was not excavated, but the north half was taken

down to undisturbed soil. The accumulated deposits in the entrance hall

were also removed down to the flagstone floor. Two distinct zones of

fill were visible inside room B: (1) a thin layer of dark material

containing a great deal of charcoal and some artifacts, resting on

sterile subsoil and ranging in thickness from 1 in. to 4 in., and (2) a

heavy accumulation of building stones and other debris extending from

the charcoal layer to the surface, 4 to 5 ft. thick. The artifacts from

the two strata were studied separately in the distributional

analysis, the artifacts from the entrance hall being included with those

from the upper stratum.

Room C. The area between room A and Room D was designated room

C (Fig. 23), although after excavation it became doubtful that there

ever was an actual enclosed room there. The west wall of room A formed

room C's eastern boundary and the east wall of room D its western

boundary; a stone wall connecting the southwestern corner of room B with

the northeastern corner of room D formed its northern boundary. There

was no evidence of a wall on the south side of room C. Perhaps the room

C area functioned primarily as a firebreak zone between the magazines on

the east and what was evidently a barracks (rooms D and E) on the

west.

The wall marking the north boundary of room C was made of rather

nicely squared stones of varying sizes (Fig. 33). Two feet wide and

still standing several feet above ground in 1965, this wall was abutted

squarely against, but was not bonded into, the southwest corner of room

B. The north face of the wall was flush with the north face of room B's

south wall. A corresponding stone wall extended eastward from the

southeast corner of room B (see Fig. 23). The south wall of room B, it

will be recalled, was originally the north exterior wall of the brick

magazine (room A) before the stone magazine (room B) was built. The two

stone walls which, in effect, extend that wall east and west were

probably added before the stone magazine.

Inside room C, against the stone wall at the north end of the room,

were two stone and brick lined, rectangular pits that evidently were

built as latrines but which ultimately were used for disposal of trash

(Figs. 33, 34). Measuring 4ft. wide, 6 ft. or 7 ft. long, and 3 ft. or 4

ft. deep, these pits yielded more artifacts than any other part of the

structure 2 complex, most of them seemingly dating from early to

mid-19th century. A layer of soil containing a small quantity of

occupational debris had accumulated over the bedrock and sterile glacial

till which constituted the subcultural floor of the room C area outside

the two latrine pits, but it produced no material of particular

significance.

33 View of the north end of room C, structure 2, looking north. The

wall connecting rooms B and D is facing the camera; the two latrines are

at its foot.

|

34 View looking straight down into latrine 1, room C, structure 2.

|

Careful inspection of the walls, foundations, drains, and other

structural remains in and around room C led to the conclusion that the

latrine pits and the room's north wall were contemporaneous and that

both postdated the brick magazine (room A) and predated the stone

magazine (room B) as well as the barracks (rooms D and E).

For analysis of artifact distribution, the deposits within room C

were divided into three areas: (1) the east latrine; (2) the west

latrine, and (3) the floor area outside the latrines. The deposits in

the floor area, only about 1 ft. in maximum thickness, were separated

into two units, upper and lower. Artifacts from the more than three feet

of deposits in the ash pits were plotted by the levels of

excavation—three inches each in most instances.

Rooms D and E. Contiguous to room C on the west lay the stone

foundation and lower walls of a rectangular building, its long axis

running roughly east and west (Figs. 23, 25). It was divided into two

sections—designated rooms D and E respectively—by a

jerry-built cross wall of brick. This clearly represents the remains of

a substantial building which can confidently be identified as building

59 of the historical base map, a barracks built in 1831 (Ingram

1964:32).

The exterior walls were 2 ft. thick. The exposed stones on their

inner and outer faces were squared and neatly fitted together (Figs.

35-37); the core of the walls, however, was of mortared rubble. In 1965,

the walls were standing to what appeared to be the level of the original

wooden floor, which of course had disappeared long ago; in other words,

these were the walls of the barracks basement. Bedrock at that

particular spot sloped downward steeply to the north, and the footings

of the south wall together with those of the southern portions of the

east and west walls were set directly on bedrock (Fig. 35). The north

wall and adjacent parts of the east and west walls, however, were

footed on glacial till and stood considerably higher at floor level than

the south wall because of the steep gradient of the ground.

35 Interior south wall of room D, structure 2. Note how foundation

has been laid directly on glacially polished bedrock.

|

36 Chimney base at east wall of room D, structure 2, view looking

north.

|

37 Interior west wall of room E, structure 2. Bedrock at lower left,

top of brick partition wall at bottom, unexcavated balk running from

centre to bottom.

|

A rectangular buttress at the northeast corner of the barracks was

bonded into the foundation and therefore must have been built into the

original building. Other structural features included a heavy stone

chimney base set against the interior of the east wall (Fig. 36) and a

small footing evidently for a wooden pier which has long since

vanished—in the middle of room D.

The brick cross wall, which was not bonded into the exterior wall

foundation at either end, divided the barracks basement into two rooms,

the larger one (room D) to the east measuring 21 ft. by 23 ft. on the

inside, the other (room E), 21 ft. by 10 ft. The cross wall, 8 in.

thick, was built partly of yellow bricks like those of room A and partly

of red bricks that were slightly shorter than the yellow ones. The

bonding was erratic.

When excavation was begun, both rooms were filled with brick, stones,

and other rubble from the collapsed building. It will be remembered that

a house which had been built on the foundation of the original barracks

was occupied until 1956, when it burned. A major part of the rubble

appeared to have come from that house. In any case, modern (mostly

20th-century) rubble including the remains of household furnishings and other

artifacts was found all the way down to bedrock or undisturbed glacial

till over all of room D. In room E, however, there was a separate,

earlier deposit underlying this rubble which contained artifacts of

mid-19th century age almost exclusively. They undoubtedly accumulated as

trash under the building during its use as a barracks.

For distributional analysis the artifacts from room D were lumped

together as a single sample, but those from room E were separated into

two groups; an earlier one thought to correlate with the 19th-century

barracks, and a later one believed to have derived from the

20th-century caretaker's house. The earlier sample from room E came from a

stratum several inches thick which was covered over with several feet

of debris that presumably derived from the burning and collapsing of the

caretaker's house.

Other Features of Structure 2. Besides the five rooms

described above there were several components related to the structure 2

complex of buildings which are worthy of mention.

Jutting off in an easterly direction from the southeast corner of

room A was an area measuring approximately 12 ft. long by 6 ft. wide

which was paved with bricks (Fig. 24). Evidently a sort of patio, this

structure is believed to have dated from the caretaker era of the 20th

century.

Running along the outside of room D on the south side was a second

brick-paved patio 6 ft. or 7 ft. wide (Fig. 25). It began at the east

end of the room and extended for some 18 ft., about two-thirds of the

room's length. This patio may have dated from the 19th century when the

barracks was in use, but there was no way to be certain.

Extending on to the west from the brick patio, along the south side

of rooms D and E, was a poured concrete floor 12 ft. long by 6

ft. wide. This surely was of 20th-century provenience. The concrete

floor, probably for a porch, appeared to have truncated the brick patio,

which in its original state perhaps ran all the way across room D.

A system of masonry conduits draining the two magazines was

obviously intended to keep the powder storage areas dry (Figs. 23,

27-29, 39). Around the outside of the earlier magazine (room A) ran a

brick drain which was built against the outer face of the stone

foundation a foot or two underneath the ground. The floor of the drain

consisted of a single row of bricks laid edge to edge; its side walls

were formed by two courses of stretchers, a single brick wide, and the

top consisted of a single row of edge-to-edge bricks like that of the

floor. The resultant conduit had an opening that was about 6 in. square

in cross-section.

The drain for the stone magazine (room B) originated in a vertically

placed iron grate that was set in the ground approximately 2 ft.

outside the magazine's west wall, about equidistant from the two ends of

the building. The grate opened into a conduit similar to the one

described above except that the sides and top were made of flat stones

instead of bricks. The floor was of bricks placed edge to edge like that

of the other drain.

The two drains converged some 20 ft. west of the magazines and

continued as a single conduit (made like that of the stone magazine) on

across the shelf of the upper Queen's Battery to empty down the steep

hillside at the shelf's west edge. On the way it intercepted the

southwest corner of structure 4, then bent sharply to the left, a

route suggesting that the drain was designed to serve not only the two

magazines but structure 4 as well.

In room C, just below the surface of the ground, a short section of

brick drain was exposed. It was V-shaped in cross-section and was not

covered. A narrow floor was composed of a single row of bricks set end

to end; each side, angling up from the floor at perhaps 30 degrees off

the horizontal, was made up of a single row of bricks placed edge to

edge. This drain was laid over the fill of the west latrine and clearly

was of relatively recent, probably 20th-century, vintage.

Structure 4

Structure 4 was represented by only two components: a brick hearth

and a single course of dry-laid stones forming a straight,

three-foot-wide footing some 16 ft. long (Figs. 23, 38, 39). The line of

the footing ran approximately northeast and southwest, paralleling a

bedrock scarp about 15 ft. to the northwest. The area between the

footing and the scarp was filled with stone rubble. The brick hearth lay

at the base of the scarp opposite the east end of the footing.

38 Structure 4 wall foundation, view looking northeast.

|

39 View from top of low scarp at north edge of upper Queen's Battery,

looking down into structure 4 area. Brick hearth at lower left,

structure 4 foundation wall and drains from rooms A and B, structure 2,

at upper centre.

|

The face of the scarp had been straightened and dressed off to make

it more vertical, in much the same manner as had the scarp in the lower

Queen's Battery area against which the north wall of structure 3 was

built. Structures 10 and 11 were built in a similar way; that is, with

their north walls against sheered natural scarps.

In view of the similarity of the structure 4 remains to the pattern

established by structures 3, 10, 11, it appears likely that a wooden

building occupied the structure 4 area at one time, its south wall

standing on the stone footing and its north wall set right against the

scarp. The hearth, in that case, would have served a chimney in the

northeast part of the building. This is conjectural, however, as no

wall foundations were present where the east and west ends of such a

building would have been, nor was there any trace of a foundation along

the base of the scarp where the north wall would have stood.

Miscellaneous Features

In addition to structures 2 and 4, additional structural features

were unearthed at the upper Queen's Battery; a pit containing

20th-century trash (evidently the caretaker's privy), and two stone

walls that met to form a right angle (Fig. 23). One of the walls, about

40 ft. long, ran alongside the north wall of the barracks (rooms D and E

of structure 2). A space of four or five feet separating the wall from

the barracks was filled with stone rubble. From the southwest end of

that wall, at right angles, extended the second wall, 23 ft. long. The

latter ran across the end of the shallow depression lying between

structure 2 and the scarp at the northwest edge of the upper Queen's

Battery. As the shallow depression drained naturally down a steep cliff

at that end, the wall was probably designed to check loss of the scanty

topsoil by erosion.

Testimony of the Caretaker

On July 16, 1965, Mr. Walter Boone, who claimed to have lived in the

caretaker's house for 22 years, was interviewed by Mr. Woodall. The

exact dates of Mr. Boone's residence were not ascertained, but he must

have lived there between 1900 and the time the house burned, apparently

in the middle 1950s. The following notes on Mr. Boone's testimony were

made by Mr. Woodall.

Mr. Walter Boone, who lived in the barracks-magazine complex for

22 years, came out to the site this afternoon to point out what he could

concerning the age of walls, original features of buildings,

etc.

The brick patio adjoining the east wall of the magazine (Room A)

was laid by Boone, and is therefore modern in age.

Concerning Room A proper, Boone stated that the door on the north

wall was at one time a thick, very heavy wooden door secured by metal

hinges to the outside, and the door opened outward from the building.

Boone said a wood floor, laid along the top of the interior footing, was

in place when he lived in the building. Also a wood floor was in the

hall between Rooms A and B. The windows in Room A were there when Boone

occupied the place.

[Room B] was in a state of ruin when Boone moved into the

barracks, although the roof was still up. The roof was arched like that

of Room A, but because of the hazard of it falling in was broken and

lowered purposely by St. John's housing officials at a late date. The

entranceway was used by Boone to hold coal, and a door was present at

both ends of the entrance as well as in the window. The bulk, if not

all, of the modern iron and metal artifacts recovered [by the

archaeologists] from clearing this room were left by Boone. None of the wooden

beams, stones, or other features of this room were done by

Boone.

[Room C] was covered by a kitchen with a porch extending to the

south, ending about 4' beyond the SW and SE corners of Rooms A and D

respectively. None of the walls were built or modified by Boone, and the

kitchen floor was level with the threshold at the west end of the hall

between Rooms A and B.

[The area comprising rooms D and E was] the main living quarters

for Boone and his family. The floor level was at the interior

footing#151;remains of the wood beams are still visible on this footing. It

was partially supported by a brick pillar in the centre of the room; the

cement foundation of this pillar is visible. A door was present at the

northeast corner in the east wall; in the middle of the west wall, and

in the south wall by the cement porch (not laid by Boone) were two

doors, one opening into the Room E area, the other into Room D. The

brick wall separating Rooms D and E extended all the way to the roof at

the time of Boone's occupation. Boone's privy had been located in the

area of Lots 4-9 of 1A6B [the area where the previously mentioned pit

was found]. Windows in Rooms D and E had been present on the north,

west, and south sides, but most of them were located high on the wall

and their exact locations cannot be determined. At least two were on the

north and south sides, and at least one on the west end.

Besides the privy located at 1A6B4-9, the west wall [the

designation for the retaining wall running across the down-slope end of

the shallow depression] had been built by Boone. The south wall [the one

at right angles to the west wall] was repaired by him, but it and the

rubble fill between it and Rooms D and E were in place when he moved

in. The wall in 1A6C [structure 4] and the hearth in 1A6B [structure 4]

where not known — Boone stated that to his knowledge no construction had

been done in this area in recent years. A drain had been built by Boone

down the slope to the west, behind Room E. None of the "French

drains" [those draining the magazine areas] were built or modified by

him, except one part of the drain now being exposed in 1A6R where it

meets the west wall.

History of the Queens' Battery Area

Installation of the gun positions at the Queen's Battery was begun in

1796 and presumably was completed the same year (Richardson 1962: 6).

Probably levelling of the lower Queen's Battery area was done at the

same time. There seems to be no record of exactly when the 50 ft. by 13

ft. wooden barracks at the lower Queen's Battery (structure 3 of this

report; building 35 of the historical base map) was built, but it is

reported to have been standing in 1812 (Ingram 1964; 28). In 1831, it

was torn down and replaced by a more substantial barracks at the upper

Queen's Battery (structure 2, rooms D and E of this report, building 59

of the historical base map) (Ingram 1964; 8, 32).

The brick magazine (structure 2, room A) and the stone magazine

(structure 2, room B) cannot be individually correlated with documented

structures. However, they are probably buildings 36 and 52 of Figure 4,

even though Ingram (1964; 29, 31) states that both buildings were brick.

There seems to be no contemporary reference to a stone magazine.

| Chronology for the lower Queen's Battery |

|

| 1796 | Lower Queen's Battery area levelled (zone E deposited) |

|

| 1796-1840(?) | Zone D deposited |

|

| 1809-1812 | Structure 3 built sometime during this period |

|

| 1831 | Structure 3 torn down |

|

| 1840(?)-1870(?) | Zones B and C probably deposited during this period |

|

| 1870(?)-1965 | Zone A deposited |

|

Dates for the paved areas at the lower Queen's Battery (structures 5,

6, and 7) are uncertain, but they predate the traverse tracks and

consequently were probably installed before 1860.

| Chronology for the upper Queen's Battery |

|

| Before 1831 | Brick magazine (structure 2, room A) built; north wall of room C,

structure 2 built (after brick magazine) along with latrines |

|

| 1831 | Barracks (structure 2, rooms D and E) built |

|

| After 1831 |

Stone magazine (structure 2, room B) built (probably before 1870) |

|

| 1820(?)-1860(?) |

Cultural deposits in latrines probably accumulated during this period |

|

| 1831-1860(?) | Lower level, room E of structure 2 deposited |

|

| 1860(?)-1950s | Upper level, room E of structure 2 deposited |

|

No accurate estimate can be given of the date of structure 4, but it

may well have predated the barracks built in 1831.

|