|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Lake Bennett, British Columbia

by Margaret Carter

Inseparable Destinies

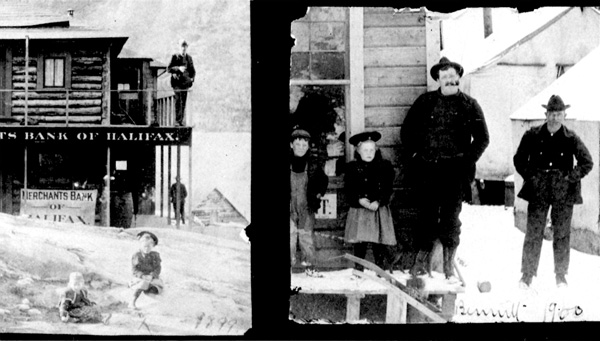

Part of the reason for the importance of the church in Bennett by

late 1899 and early 1900 was the changed nature of the town. During 1899

many men brought their wives and children north1 (Fig. 63),

and their presence had an undeniable effect in drawing community life

closer to the church.

63 Bennett, 1900.

(Hazel Hartshorn [Gloslie].)

|

The hotel, the church's major contender as a social centre, was also

undergoing substantial change. In the spring of 1898 when Martha Black

passed through Bennett, she commented "there were two or three so-called

hotels, canvas roofed, wooden affairs, each of which had a kitchen,

dining room, bar and dance-hall in one room."2 These hotels

also provided sleeping place on the floor at night, and gambling was

certainly a preoccupation in some of them. Any traveller who wanted a

place to eat, drink, sleep, or meet his fellow man was forced to spend

some of his day there. As time passed, the hotel's role as hub was

gradually reduced. Mounted Police enforcement of a no-work Sunday

regulation assisted the division of functions.3 Before long,

respectable hotels which provided food and accommodation appeared, and

all other activities were relegated to a separate institution, the

saloon.4 As the saloon's entertainments could only be reached

by deliberate intention, participation in its activities often caused

moral indignation and by 1900 gamblers were even asked to leave town.

All of these things, of course, are signs that Bennett was forgetting it

was a northern boom town and adopting southern "civilization."

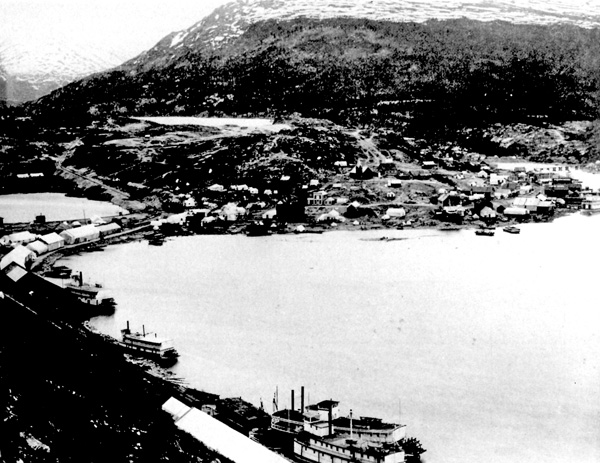

By 1899 when Sinclair began to build the church, the town was

thriving on what many thought would be a permanent base. After the

throngs of gold-seekers disappeared in 1898, Bennett became the

transshipment centre for goods moving to the gold-fields at Dawson and

Atlin (Fig. 64). Fleets of sternwheelers (Fig. 65) and scows (Fig. 66)

carried goods away from Bennett to their destinations. The goods arrived

in Bennett from the south in a variety of ways. They were carried over

the Chilkoot Pass on aerial tramways (Fig. 67) to Crater Lake where they

were put aboard crude carts on rails that took them to Bennett (Fig.

68). They came over the White Pass first in wagons on the Brackett Wagon

road that was completed to Bennett in 18995 (see Fig. 69),

then as far as possible by train as stages of the White Pass and Yukon

Railway were completed. Some of these companies headquartered in

Bennett: most of them had warehousing facilities there. As soon as the

railway reached the summit of the White Pass it became the preferred

route for passenger traffic (Figs. 70, 71).

64 Bennett, 1900.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

65 The Steamer Gleaner that ran from

Bennett to Atlin.

(Hazel Hartshorn [Gloslie].)

|

66 W. B. Copping's party arriving in Dawson,

October 17, 1900 with 5 scows and 100 tons of merchandise. These

goods were transshipped at Bennett.

(University of Washington.)

|

67 The aerial tramway that operated on the

Chilkoot Pass.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

68 The cart that completd the tramway operation

between Crater Lake and Bennett before completion of the railway.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

69 Freighting goods by waggon. This is probably one

of the Red Line waggons that operated out of Bennett.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

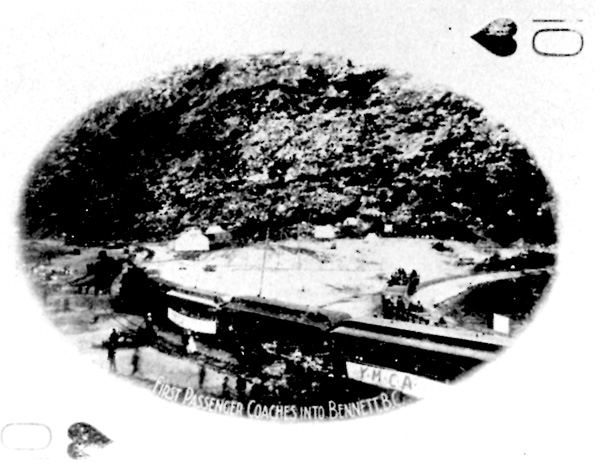

70 Driving the golden spike at Bennett, 6

July 1899.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

71 First passenger coaches into Bennett, B.C.

(Washington State University, Pullman.)

|

Passengers stayed in Bennett hotels, banked in

Bennett banks, and often they outfitted in Bennett stores. Employment in

these industries provided a constant reason for five to six hundred

people to remain in the town.6

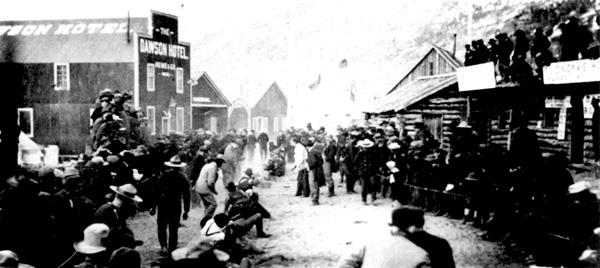

Although there was a fairly high turnover in the

bodies that comprised this figure,7 between 1899 and 1900

most Bennett residents remained long enough for a sense of community to

develop. Concern for the industries that fed the town's prosperity was

common to all, and they took pride in noting the physical manifestations

of success. Every time a two-storey hotel sided with corrugated iron was

constructed (Fig. 72), the event was heralded in the pages of the town's

most enthusiastic booster, the Bennett Sun. The Sun also

delighted in recounting the shock new improvements caused men who had

not been to Bennett since 1898.8 St. Andrew's Church, Lake Bennett,

profited from this growing community spirit in the support and

encouragement it received, for the period of its construction capped the

height of Bennett's prosperity.

72 Tuf of War, 1900 — a sign of Benntt's new

community spirit. The Dawson Hotel and the warehouses in the distance

on the left are covered with corrugated iron.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

In fact, the condition of the Presbyterian mission at Lake Bennett

parallels gold-rush developments at that centre closely. The mission was

established early in 1898 just before a throng of gold-hungry men

arrived to await spring breakup on their way north. At that time the

church building was temporary, a log shack similar to those used by

old-time northern miners. It was sufficient because the church received

so little support that it was all that was required. The few men it was

attempting to serve were preoccupied with their push north over the ice

in a single-minded drive to meet worldly ambitions. This attitude

moderated as more men were trapped in Bennett waiting for the spring

breakup of 1898. A proportion of such a large crowd of southern men

would inevitably be interested in the church, and this is reflected in

increased financial support and attendance at services. A canvas church

was constructed to accommodate them. After the Klondikers left, Bennett

itself hung in a limbo of little activity until the railroad reached the

summit of the White Pass and it became an easy matter to ship goods

north in quantity. During this period the Bennett missionary, Sinclair,

spent most of his time in Skagway and in the railway camps, devoting

little selective time to town. Such services as were held, took place in

Bennett's hotels on an irregular basis. Once Bennett began to fulfill a

major role in the territory's transportation network, however, the town

showed signs of becoming better established. It was then that Sinclair

built a permanent church with the assistance and approval of its

residents.

The close relationship that existed between the church and the town

of Bennett provides the inevitable explanation for the end of church

activity. As has already been indicated, by 1899 Bennett had become the

transshipment hub for goods moving north. During most of 1900 it thrived

on this role; however, late in that year the White Pass and Yukon

Railway was completed to Whitehorse. This event alone relocated the

transportation centre for the Yukon in Whitehorse, and along with it

went most of Bennett's population.9

The Reverend J.A. Sinclair participated in the exodus. As early as

1899 he had identified "Closeleigh," or Whitehorse, as a possible area

for development and had obtained a church lot there.10 Late

in 1900, when it became evident that some development would shift to

that point, he moved there to establish a church. At the time he left,

Sinclair felt "the future of Bennett is somewhat

problematical."11 Earlier he had speculated that the scow and

sailboat trade that operated from the town would keep it

alive.12 This trade quickly supplied the Dawson market with

fresh produce and filled its food shortages. Sinclair's predictions

might have come true if developments at Dawson had continued to expand,

and if railway rates had been high. As it was, not only were the rates

competitive, but mining in the Dawson area was mechanized and "the

Eldorado" stabilized at a population below that of 1900. This precluded

the demand for an extensive scow and sailboat trade.

This situation was not clear when the Reverend R. James Russell

arrived from Schreiber, Ontario, to take Sinclair's place in Bennett in

the fall of 1900. Russell continued church functions in Bennett until

1902 when the population had shrunk to a handful because there was no

employment. At this point he moved to take John Pringle's place in the

mining area at Atlin where his services were required.13 With

his move, the church was abandoned.

|