|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Lake Bennett, British Columbia

by Margaret Carter

Building a Church

Just before he left Skagway to move to Bennett in May

1899, Sinclair took precautions to ensure that he had a proper

title1 to the third piece of "church" land, the last lot he

had filed on in the fall. When Harrison arrived in Skagway the weary

Sinclair moved to Bennett. There he saw "some professional lot stakers

taking a suspicious interest in my new site"2 and decided he

urgently needed a new building to hold it. Consequently, he ordered

7,000 feet of rough lumber at $100.00 per thousand and laid a foundation

and board floor with the help of some volunteer labour.3 The

following Sunday a church service was held in a borrowed tent pitched on

the floor (Fig. 30), and the tent remained there several weeks while a

church building was constructed Yukon-style around it (Figs. 31 and

32).

30 "Preaching, Mushing and Carpentering all in the same suit, May 1899."

This photograph shows the early tent church as it received its congregation.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

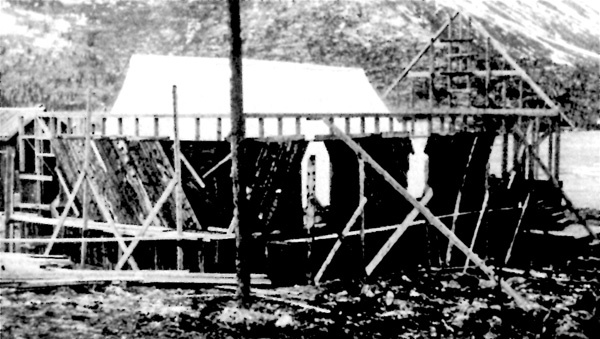

31 "I lay the foundation floor upon which I pitched the tent."

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

32 The exterior of the church progressed quickly.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

By 24 May 1899, sufficient work had been completed on

the building to permit a celebration for the laying of the cornerstone.

John Hyslop, C.E., assistant chief engineer for the White Pass and Yukon

Railway, was master of ceremonies for a programme of music and speeches

that culminated in the appointment of a building committee to solicit

financial support. Activity around the new church seems to have captured

the attention of a community spirit new to Bennett for Sinclair wrote

that his building committee was composed of a Roman Catholic, a

Congregationalist, two Episcopalians and two Presbyterians. "When the

average citizen saw this 'priest' bearing down on him" quipped the 31

May Bennett Sun, "his hand immediately sought his pulse." All

agreed that the first church on the ground should receive united

support,4 no small feat in an era of rigid religious

definition.

By the first of June 1899, a crude building had been

constructed around the tent, and the tent was removed and returned.

Sinclair described the structure in the following way: "The roof was of

rough lumber, tar paper and slabs, the floor of rough lumber and the

windows of cotton."5 The walls were of saw-jointed slabs,

readily available in local sawmills.

Herein lies the mystery of St. Andrew's Church, Lake

Bennett. Had the building remained as Sinclair described it in June

1899, the oral tradition that the church was an unfinished structure

built in the midst of the gold-seekers' tents might have been partially

credible.6 As the summer of 1899 wore on, however, plans for

the construction of the church continued. In July, Sinclair wrote to his

friend Dr. Campbell in Victoria, requesting the windows needed to

complete the structure: "we shall require seven munion windows to fill

openings 3'-10" x 5'-10", three triple windows for the front to fill an

opening 7'-0" x 9'8", also a door with a gothic transom to fill an

opening 28'-10" x 9'8-3/4"."7 He inquired whether Dr. Campbell's church

would be able to donate the windows, as

there were no suitable materials available in

Bennett. When these windows arrived, they were of leaded cathedral

glass,8 quite a sophisticated material for a wilderness

church! (Fig. 33).

33 A close look shows the leaded glass windows.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

Many a veteran Yukon miner would have wondered what

all the fuss was about. Low log buildings windowed with "bottle glass,"

roofed with sod, and chinked with mud had long ago proven successful

(Fig. 34). These structures were built of materials at hand for the

practical purposes of shelter and warmth with little thought to

aesthetics.

34 House with bottle windows.

(University of Toronto, J.B. Tyrell Collection.)

|

Clearly, both the physical and spiritual elements of

building concerned Sinclair as he drew up the plans for the Bennett

church. His letters reveal that he attempted to shut out Yukon winters

by leaving a dead-air space of 4 inches between the inside and outside

walls.9 Building paper was bought at Bennett at $4.00 a

roll10 and applied tightly to the inside surface of the

outside wall (Fig. 35). Window and door frames were caulked with oakum, the

familiar boat-building compound, and the floors were ventilated to take

off the draft and save the heat.11 The roof was

shingled,12 and chimneys for fireplaces were located at

either end of the building. "So I have demonstrated that one can be

perfectly comfortable in this country and with little cost if they build

right," Sinclair proudly wrote to his father and early carpentry

instructor13 while surveying the success of his design.

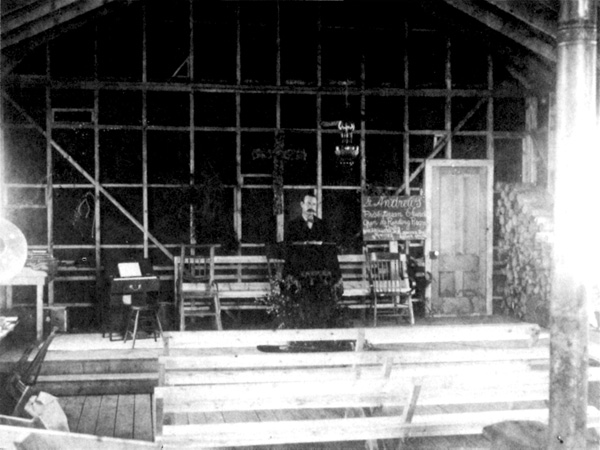

35 Interior of Bennett Church showing the building paper and the

framing before the interior walls were put in place. Arthur

Copeland, Sinclair's lay assistant, sits at the desk. The

small organ Sinclair brought north with him is on the left.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

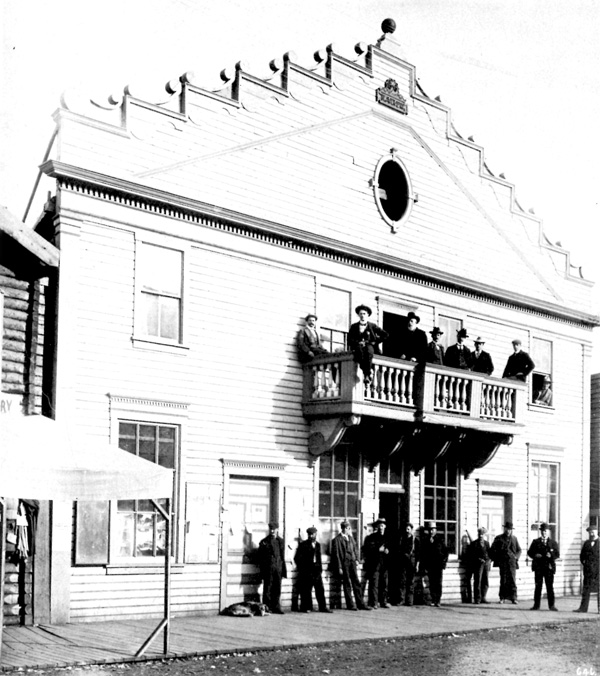

The church at Bennett Lake was probably the most beautiful building

"inside" when it was completed. Dawson certainly had nothing that could

compete with the sophisticated traditionalism of its design at the time.

Most of its "substantial" structures looked wonderful from the front

where fancy boom-town façades gave the appearance of design, but from

the side and rear their true common-log characteristics were evident

(Fig. 36). Many of the "City of Gold's" public buildings did not even

make that pretence. Figure 37 shows the squat but serviceable log

structure that functioned as Dawson's courthouse until 1902 when a

classical revival building (Fig. 38) more in keeping with its role was

constructed. Indeed, Dawson City's Anglican parishioners were attending

the small log church seen in Figure 39 until at least a year after St.

Andrew's, Lake Bennett, had been completed. Only between 1901 and 1903

did the Anglicans, Presbyterians and Roman Catholics (Figs. 40-42)

settle down to building "proper" churches. The reasons for Dawson's

seeming slowness are two: first, transportation facilities did not yet

exist to import sophisticated materials that were not locally available;

second, the future of the boom-town was uncertain and its "residents,"

concerned only with utility, were not willing to risk the expense of

buildings that would last.14

36 This magnificent building is shown with log side walls in

Public Archives of Canada photos, PA 13442 and PA 13324, although

they display the façade to less advantage.

(Public Archives Canada, C 18622.)

|

37 Early Dawson Court House.

(T.G. Fuller, Ottawa)

|

38 New Court House, Dawson.

(Vancouver Public Library)

|

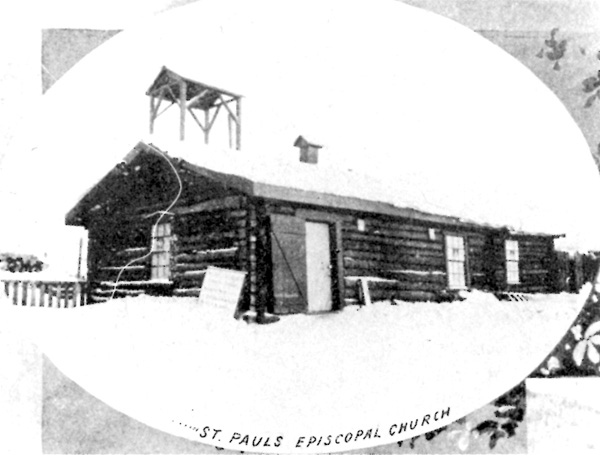

39 St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Dawson, until 1901.

(G. Cantwell, The Klondike A Souvenir [n.d., ca. 1908], p. 58.)

|

40 St. Paul's Anglican Church, Dawson.

(T.G. Fuller, Ottawa.)

|

41 Side view of St. Andrew's Church, Dawson.

(University of Toronto, J.B. Tyrell Collection.)

|

42 St. Mary's Church and Hospital, Dawson.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

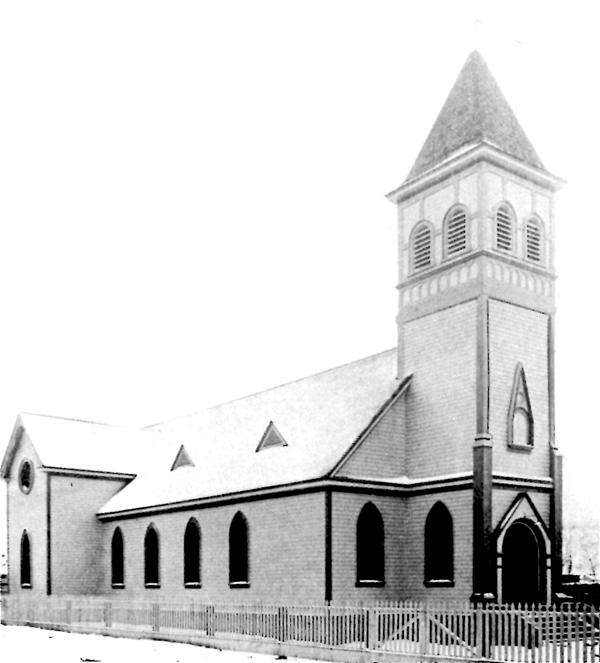

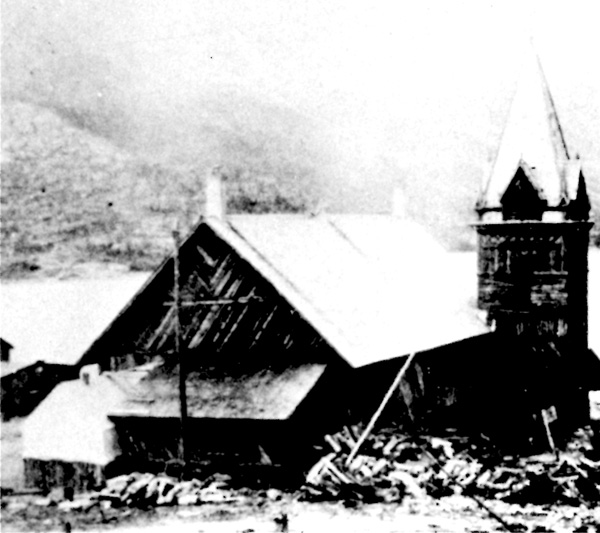

Both of these factors are also relevant to Sinclair's

design of the Bennett church. Examination of Figures 43 and 33 will

reveal that it adheres to the gothic revival tradition in its

elements.15 A spire tops its tower above a lattice border. In

itself, the spire is relatively ornate, supporting gables with vented

double windows that arch to a point. Decorative finials grace its

corners. While the main part of the building is relatively simple, with

a rectangular shape and single gabled roof, its windows do gently curve

to a barely perceptible point. The later Dawson churches (Figs.

40-42) also show evidence of gothic revival characteristics, and it

is interesting to note that they were — and still are —

commonly used in churches in "civilized areas." Indeed, it has been said

that gothic is "the only proper style" for use in that type of

structure.16 While the all-inclusive implications of this

statement may occasion some debate, the important issue here is why so

sophisticated a structure appeared at all in a frontier area.

43 Church at Lake Benneett, 1949.

(Yukon Archives, MacBride Museum Collection.)

|

Clearly, the Bennett church is in the gothic revival

tradition because Sinclair designed it to be so. It is, therefore,

necessary to examine the man a little more closely at the time he

conceived the idea. In March 1899, before he had even located in

Bennett, he wrote to Rev. Robert H. Warden in Toronto that he expected

it would become the main distributing centre for the Atlin and Klondike

gold-fields17 — a factor that would make it a centre

second only to Dawson in "inside" importance. Sinclair may have been

planning the church at that time, and even if he was not, nothing

occurred between then and the time he drew up the plans for the exterior

to shake his faith in the "town's" stability.18 Sinclair evidently

decided to build a structure that would not only last for a long

time, but continue as a source of pride to his congregation.

As will be evident later, this was certainly in

accordance with his program of encouraging "civilized" behavioral

standards through southern-style entertainments once he had the building

in operation. Sinclair seems to have been a man who practised

"progressive" values wherever he went. An article in the Bennett

Sun of 5 August 1899 stresses this aspect of his character.

Remarking on the "noticeable improvements" on the Presbyterian mission

property, the editor commented: "If owners of lots would follow that

gentleman's [Sinclair's] example, the appearance of the town would be

greatly improved." It is consequently, not surprising that Sinclair

designed and built a traditional civilized church a little ahead of the

time that Bennett or any other town would normally have been ready for

it.

Such an undertaking is strewn with difficulties, and

it is interesting to examine how intelligently Sinclair coped with the

prevailing conditions in Bennett when planning the execution of his

design. It must be remembered that when he began his task,

building materials were in short supply, and there

was no easy way of importing them. He consequently defined the aesthetic

mood of the building's exterior — the first part constructed —

as "rustic."

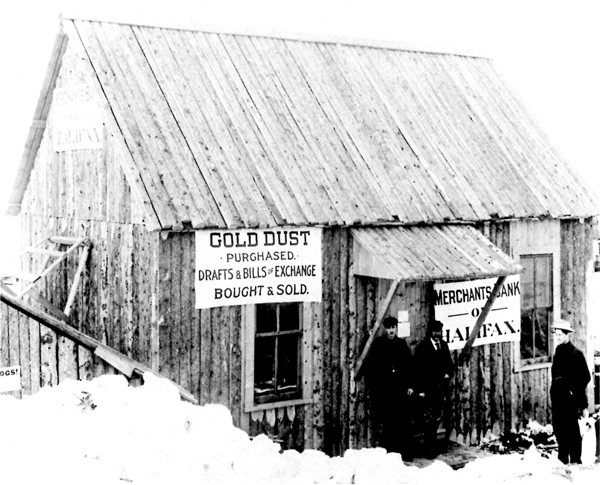

This adapted very well to the use of Bennett's unique

(and cheap) building material, split slabs. These were the rounded slabs

trimmed from the outside of logs before the main portion was cut into

lumber (Fig. 44). As they still contained their bark, they made

excellent waterproof sheathing. Most of Bennett's early buildings were

made of this material: the Victoria Yukon Transportation Company applied

them to their warehouses as both roofing and siding (Fig. 45), as did

the government telegraph office (Fig. 46) and the Merchant's Bank of

Halifax (Fig. 47). In June 1899, they sold for $40.00 per thousand,

while rough lumber cost $100.00.19 Sinclair had little choice but to

use them, for he was on a very tight budget. This is clear in Figure 43,

which shows that even the eaves were faced with them. Nevertheless, he

did employ them with distinction. Comparison of the church's siding with

that of other Bennett buildings seen in Figures 45-47 shows that

its slabs alone have been placed in a deliberate design, with a layer

on the vertical, then a layer on opposing 90° angles, then a repeat of

each of these. The slabs on the other buildings are all

horizontals.

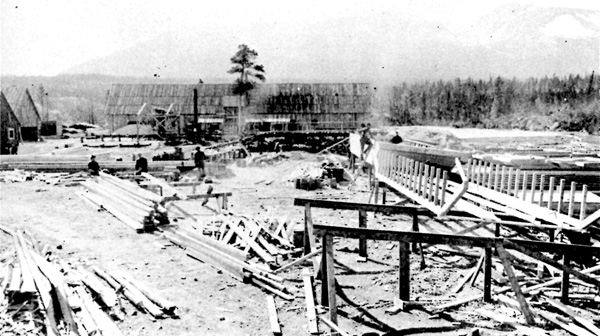

44 Sawmill at Bennett. Note split slabs at bottom left.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

45 Exterior view, King's sawmill, Bennett, 1900. Note end

walls of building on left appear to be one continuous slab,

while the long side walls and the roof are larger and

composed of several lengths. Buiding at right has walls of

shorter slabs, and may have been constructed later.

(Yukon Archives Vogee Collection.)

|

46 Goverment Telegraph Office, Bennett.

(T. G. Fuller, Ottawa.)

|

47 First bank of Bennett, 20 April 1899.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

There can be four explanations for this — and

each of them may have some truth. First, it is possible that the only

slabs available to Sinclair were short ones, left from cutting the

railway ties that would have been the Bennett mills' mainstay at the

time he built the church, while the telegraph building, the bank

building and the earlier warehouses had been made of boat lumber

remnants. If so, he may have been forced to design such a pattern as a

way out of an awkward problem. Second, even if slabs from boat lumber

cuttings were available they may not have been sufficiently long for use

on the tall church. The Victoria Yukon Transportation Company was unable

to use them on the ends and roofs of its large warehouses, even when

continuous slabs could be applied on the sides (Fig. 45). Third, he may

have felt the building needed extra strength. As Figure 48 shows in the

construction of Dawson Telegraph Office, this was often provided through

diagonal sheathing. Such sheathing was usually composed of a separate

layer of rough boards and then covered with clapboard (as was the

telegraph office, Fig. 49) or another exterior material; however, at

Bennett prices this layer would have cost Sinclair two and a half times

the price of his "finishing" material; and so the fourth possible reason

for his decision is evident — cost. At least two other examples of

the use of a "patterned" single layer of boards for the exterior finish

of a building have been found in Canada: one in Peterborough, Ontario (Fig. 50),

and the second in Dawson itself (Fig. 51). In both of these cases as in

the Bennett church, the boards used are short. In Dawson's Palace Grand

the use of this type of construction was certainly also forced by the

availability of material, for the building was made of the hull of a

wrecked sternwheeler at a time when lumber was at a premium in the town.

Here also it was occasioned by the desire for strength with an

accommodation to aesthetics; the theatre was one of Dawson's first

public buildings, and its entertainment value was based on its ability

to impress paying customers with its glamour.

48 Telegraph Office, Dawson. The structural under-layer of

boards is being applied.

(T. G. Fuller, Ottawa.)

|

49 Telegraph Office, Dawson, with final siding almost

complete.

(T. G. Fuller, Ottawa.)

|

50 271 Simcoe St., Peterborough, Ontario has similar siding.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

51 Dawson's Palace Grand (Savoy) Theatre in 1901. Note the

use of diagonal wall material here also.

(Yukon Archives, Vogee Collection.)

|

52 Similar windows are found in this church in Gravenhurst,

Ontario.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

With the arrival of the railway in Bennett in July

1899, the restrictions on the material Sinclair was able to use to

complete the church's exterior eased somewhat. It is worthy of note that

he wrote Dr. Campbell to order his windows during that month. It is also

interesting to note that the windows he ordered were a pointed gothic

style (Fig. 29) although he wanted them made to be set in an easily

built square frame (Fig. 34). As Dr. Campbell was in Victoria, it is

probable he had the windows custom-made20 on Vancouver

Island, then shipped north.

At some time in Victoria the window design was

altered from a true gothic to an arch with a slight concession to a

point. The reason for this change is not evident; however, it is

possible that Dr. Campbell and the designer decided to sacrifice gothic

purity for shipping security in the required frame shape. This was a

compromise Sinclair was also willing to make, for although he tried to make

use of the southern facilities that would make his task easier, he was

careful to keep the tone of the design consistent. He reminded Dr.

Campbell that the windows "will require no facing on the outside as they

must be fitted with rustic slab facings to correspond."21

Sinclair also imported shingles as a roofing material sympathetic to

his intentions, for they are not found on earlier buildings. The

exterior of Bennett church was a curious but successful combination of

frontier necessity and civilized taste.

The labour that constructed it straddles the

transition from frontier to traditional behavior as well. Although

Sinclair seems to have participated in the shingling and some of the

later dirty jobs himself, Bennett carpenters performed the finishing

work under his supervision at the rate of $5 a day.22 While

several accounts of people living in Bennett in 1899 include passages

stating they voluntarily helped build the church,23 this was

almost certainly the early work of raising the outside (Fig. 53) and not

the later finishing detail. Sinclair's papers make no reference to

voluntary assistance during the later period.

53 Sinclair and some of his helpers. Note the

bell is the same as that shown on Grant's "church," Figure 15.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

For the second, more time consuming portion of the

construction, donations seem to have taken a much less arduous, more

civilized form. The Northern Pacific Navigation Company carried lumber

at the low rate of $5 per thousand, and the captain of the Rosalie

transported all building materials "free" from Vancouver and

Victoria to Skagway.24 From there, the White Pass and Yukon

Railway, remembering Sinclair's role in their recent strike, extended

the same favour and carried the materials to Bennett on their newly

completed line — a service that Sinclair later evaluated at almost

$1,500.25 The Victoria Yukon Transportation Company, a Victoria firm

which operated both a sawmill and boat-building business at Bennett,

donated $100 worth of lumber through its manager, Mr. King.26

Mr. Partridge, a sawmill owner at the far end of Lake Bennett and an

active member of the congregation, provided unspecified "help with my

church."27 J.B. Charleson, superintendent of the Department

of Public Works at Bennett donated $200.00 toward construction in lieu

of applying his considerable talents as a building aide.28

"In the same way almost everyone approached has done splendidly in

proportion to their means, so that, operating roughly, today we have a

building worth $4,000.00 with so little debt that with slight assistance

we can remove it all next spring."29 The community of Bennett

supported the construction of "their church" in a full-hearted but

traditional way. Their final donation, a pipe organ (Figs. 54 and 55) to

replace the portable one that Sinclair originally brought north with

him30 (Fig. 35) adds credence to the suspicion that the

lonely Klondikers regarded the church as a symbol of the values of home

away from home.

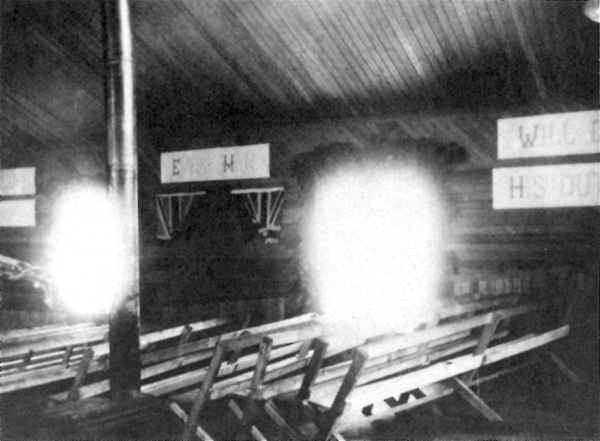

54 "Our pretty little church is the most

popular rendez-vous in Bennett." Note the tables for reading and

writing along the side walls.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

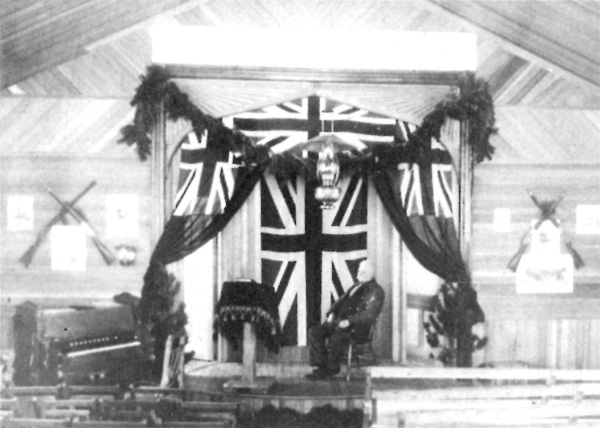

55 Bennett Church decorated for a patriotic

meeting marking the Boer War. The church played an important social

role in Bennett.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

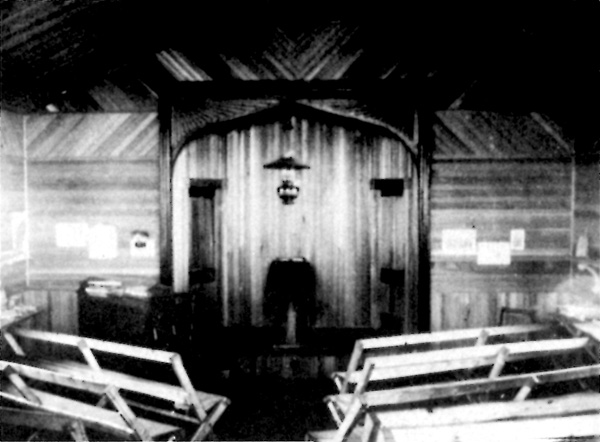

This was, in fact, an attitude that Sinclair

considered carefully as he planned the interior of the church. The

building itself was 24 by 50 feet with a 10-foot square tower containing

a new bell31 and vestibule. Inside the vestibule was the

"congregation" area, which occupied most of the interior. It was lined

with sawn lumber, probably the same pine mill ends as were on the

exterior (as pine was the only wood suitable for finishing construction

cut in the area).32 They also were arranged at angles to

create a visual pattern. Those closest to the floor were vertical to

provide an impression of wainscoting, while the next layer was

horizontal (Fig. 56). Just under the roof line, a shallow band of boards

at a 45° angle slanting toward the front of the building drew the eye

toward the "platform" where the preacher held the service (Fig. 54). At

the front of the building (and presumably also at the back), where the

A-shaped end extended higher, these boards were counterpoised by lumber

of a similar width on an opposing 45° angle. This served to create a

sunburst or halo effect over the "platform" (Fig. 55).

56 Another view of the interior.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

The 'platform' itself was semicircular at the front

end which projected toward the congregation. It was "about 11 ft. square

(— all but a little corner off each)"33 and projected

back to an alcove between two rooms at the rear of the building. An arch

surrounded it "over the preacher's head"34 on the surface of

the main wall. As the arch was "gothic . . . the same style as the

arches on the main windows,"35 it was probably imported with

the window material. At the back of the platform, two doorways cut

diagonally on the corners were also faced with imported doors. Both

doors and mouldings shown in Figure 55 were common in southern Canada

in 1900.

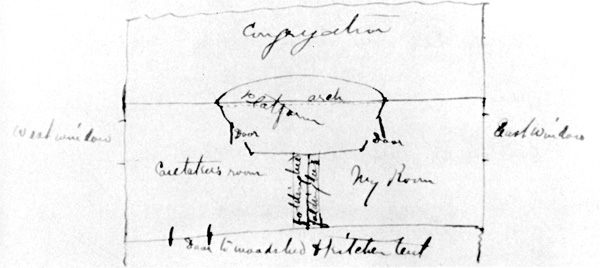

Figure 57 is a rough diagram of the rear portions of

the building that Sinclair drew for his wife. It shows the two tiny

rooms that were closed off in the back — one for Sinclair to use as

an office and sleeping room, the other for a Mr. and Mrs. Bindley and

their eleven-year-old boy. The Bindleys kept the premises in order in

exchange for rent, and in addition Mr. Bindley, "a professional

organist with fifteen years experience in London, England"36

played the new organ. Cooking was done in a combination woodshed-kitchen

tent which extended off the back of the building (Fig. 58). There seems

to have been a wooden kitchen shack added later37 (Fig. 59).

Although Sinclair wrote to his wife that the interior of the Church "is

an entirely new and original arrangement that I am designing as I go

almost," it seems to have been very successful. "I think that the

comfort of the building and the homelike surroundings has much to do

with the interest being taken by everyone in our work."38

57 Sketch of the front surface area of the

interior of building that Sinclair drew for his wife.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

58 Note the man near the white tent. He is

standing where the shack is to be located.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

59 St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, showing the

shed and 'Yukon' addition.

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

|