|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Lake Bennett, British Columbia

by Margaret Carter

Founding a Mission

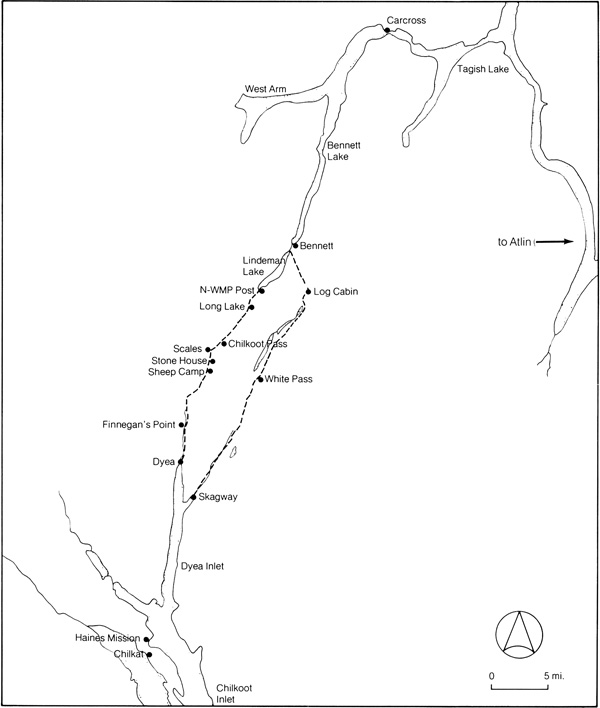

In 1897 the Reverend J.M. Dickey, Presbyterian

minister in Skagway, marked Bennett as the next logical centre of

population. A town was already forming — a collection of tents on

the south end of Lake Bennett at the junction of the Chilkoot and White

Pass trails. Although many routes "inside" were publicized during the

days of '98, these were both old Indian routes, and the Chilkoot had

been used by white prospectors in the north for many years. They were

undeniably the most popular for men who could not afford exorbitant

steamer rates to travel the whole journey by water through the mouth of

the Yukon River. They could be reached by commercial steamer from the

south, but at the neck of the Alaskan panhandle a long self-propelled

trek began.

Although the Chilkoot and the White Pass (Fig. 1)

were regarded as the best trails, they were both arduous. The Year

Book of British Columbia written for publication early in 1898

outlined the latter this way:

WHITE PASS

The White Pass commences at Skagway Bay at the head

of Lynn Canal at which point ocean steamers may call and where a wharf

has been built for the accommodation of shipping . . . The first

four miles is an easy water grade to Four-Mile Flat, to Porcupine Creek,

up and down the side hill, is five miles; from there it is three miles

to the first bridge on the Skagway River; it is swampy for a mile and a

half to two miles to the second bridge; from there to the third bridge,

one and a half miles, there are some hills and swamp land; to the

Crossing by the Skagway is three quarters of a mile on foot, but by the

trails for pack animals it is three miles along what is known as 'Bad

Hill'. From the Crossing to the Summitt to Lake Bennett twenty-two

miles. The trail leads along the southern side of Summit Lake and

Shallow Lake to Government House and from there touching Lake Lindeman

to Lake Bennett. 1

1 The Chilkoot and White Pass trails.

(Map by S. Epps) (click on image for

a PDF version.)

|

Edwin Tappan Adney, who travelled the route late in

1897 gave a more graphic description.

Gradually, stage by stage, the trail rises,

following the sloping shelves of the bare rock, so smooth as to afford

no foothold . . . Where there are no rocks there are boggy holes.

It is all rocks and mud — rocks and mud.2

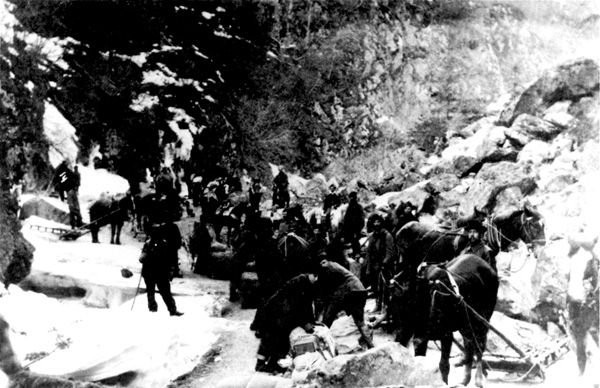

Animals and men often went lame on the trail

(Figs. 2 and 3). They were exhausted when they reached Bennett.

2 An Hourly Occurrence

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

3 Blockade, White Pass Trail.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

The Chilkoot was somewhat quicker, though no less

tortuous. It was an old Indian trail and "has always been the best in

summer,"3 explained one veteran Mountie. Unfortunately in

1898 most Klondikers travelled in the spring to reach the diggings in

time for a full season. There were so many of them that the steps

carved in the ice on the mountain side by Al Lobley

and Sam Taggart4 thawed (Fig. 4), and the presence of

would-be miners helped set off three avalanches in an already

avalanche-prone area (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, one guidebook gave

adventurers the following dispassionate description of the route:

DYEA OR CHILKOOT

From Dyea landing to the Canon is eleven miles, practically on the

level of the Dyea River flats; from the Canon to Sheep Camp is a hilly

trail five miles long, reasonable passable. Up to the Scales, three

miles, is steep and rough and the trail bad. From the Scales to the

Summit, which is an altitude of 3,700 feet, is a distance of

three-quarters of a mile, very steep and impassable for pack animals.

The distances, with bad trails all the way, with the exception of the

last mile, upon which waggons are used from the Summit are as follows:

To Crater Lake, three-quarters of a mile; Crater Lake, two miles; to

Portage, two and a half miles; to Lake Lindeman, five miles; to Lake

Bennett, one mile.5

4 White hundreds of men waited to start up the Chilkoot Pass, those

on the thin black line were climbing the steps.

(University of

Washington.)

|

5 Snowstorm on Chilkoot summit, 1898.

(University of Washington.)

|

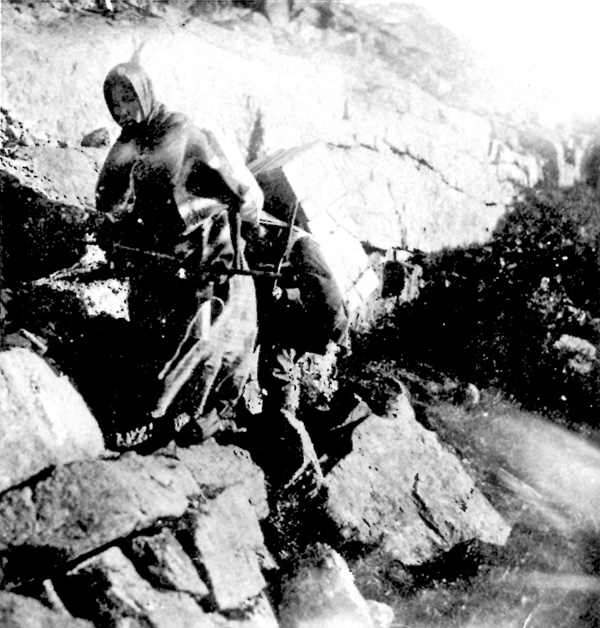

Despite its apparent difficulties,

the Chilkoot route was very popular. Martha Black reported that in July

of 1898 "the young officer told me that since the previous May eighteen

thousand men had passed the pass and I was the six hundred and

thirty-first woman"6 (Fig. 6). By the early spring of 1898 a

tramway had been built over the mountains to carry goods to Crater Lake

on the other side. Indian packers also sold space in packs like those

shown in Figure 7, but both of these services were expensive, and most

Klondikers carried goods to Bennett themselves (Fig. 8).

6 En route to the gold mines.

(Yukon Archives, MacBride Museum

Collection.)

|

7 Indian packers carrying heavy loads.

(Missouri Historical Society.)

|

8 A Klondiker totes his own load.

(Missouri Historical Society.)

|

Bennett marked the end of the trails, but these

comprised only the first lap of the journey to the gold-fields on the

southern route. The rest of the journey from Bennett to the Klondike was

made on the Yukon River itself (Fig. 9). During the winter when the

river was frozen, men continued their journey by sled. Hazardous

conditions near Miles Canyon and the Whitehorse Rapids made the second or

river half of the journey as exhausting as the early trail portion, so

Bennett grew as the half-way resting point.

9 Bruce's Map of Alaska (New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons,

1899). Section only.

(Contained as an insert in Mary E. Hitchcock,

Two Women in the Klondike [New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1899].)

|

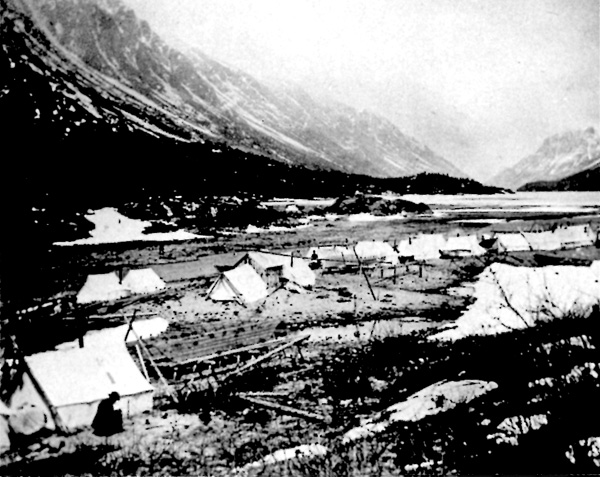

A crude centre appeared at the southeast end of the

lake as men pitched tents and took up temporary residence (Fig. 10). By

September of 1897 a sawmill had been built near the "settlement" to

provide lumber for boat-building,7 and tent stores had been

erected to buy outfits from discouraged men returning home and sell them

to the hopefuls on their way north. Canvas beaneries and saloons were

also set up. In response to this activity, the Reverend James

Robertson, Superintendent of Home Missions, decided to act on Skagway

minister Dickey's recommendation and establish a mission at Bennett.

Consequently, the second Presbyterian minister to the Klondike, Rev.

Andrew S. Grant from Almonte, Ontario, arrived in Skagway on 22

January 1898, and moved straight inland (Fig. 11). He reached Bennett in

mid-February and reported to Robertson that the journey on the White

Pass had been "the herculean task of my life."8 His comments

were similar to those of the thousands of other gold-seekers accustomed

to city life who made the trek north. "The trail is a brute," he wrote,

"but thanks to the Lord we have conquered it, and our stuff is all over

here. It would have cost our party $1,800 to have our stuff freighted

over and we took it ourselves in three weeks."9 The task

meant doubling back again and again to carry the heavy outfit along the

trail (Fig. 12). A large supply of staples had been required by the

North-West Mounted Police for entry into the country since the previous

winter when Dawsonites had almost starved to death. This made travel

quite a hardship, but it was only one of many the ordinary Klondiker had

to brave. "It is not the most comfortable thing sleeping on the snow 40°

below, and doing our own cooking but we are all right."10

10 Boat-building camp, Bennett, 1897 or very early 1898.

(R.N.

DeArmond, Juneau.)

|

11 Revs. Dickey and Grant, Presbyterian missionaries at Skagway

en route to Klondike, January 1898.

(University of Washington.)

|

12 While these men are not Grant's party the size of their outfit

gives an idea of what the ordinary Klondiker brought "inside."

(Provincial Archives of British Columbia.)

|

Despite the difficulties, Grant's sense of mission

was strong. His parting address to the civilized world reveals a

determination to succeed in the north: "When the Superintendent faced me

with the question 'will you go to the Klondike?' every personal and

selfish consideration said 'No!' but all that was best in me said 'Yes!'

But I would not go, were I not overwhelmingly convinced that I am

called."11 An impartial observer would have found his

attitude refreshing, for many have commented on "cold-bloodedness of

the gold-seeking multitude"12 found around Lake Bennett in

the winter of 1897-98.

On 28 February, Grant informed Robertson that "Those

who ought to know affirm that Bennett will have a large population this

summer."13 Even at that time, men were braving the searing

chill of Yukon winter to travel downriver by sled (Fig. 13). Few would

stop for long at Bennett until The melting ice signalled danger. Then,

there would be a back-up of men waiting for the shift to summer modes of

transportation. "I have selected a site for a Church in Bennett and

think of ordering a large tent and erecting it on this site, put a block

floor in, and a sort of framework to support the tent. We must occupy

this post at once,"14 wrote Grant to Robertson. He evidently

expected there would be a large influx.

13 During the winter men traveled on Lake Bennett by sled, continuing

their journey.

(R.N. DeArmond, Juneau.)

|

By the middle of March, Grant had built a 12 by 16

foot log cabin as a residence or "manse," as he called it, to act as

shelter from the cold. He paid gold-rush prices for his supplies, and

although he cut the logs himself, the building cost over $200 to complete.

"For three short boards for a door I paid $9.00. For the tar paper for

the roof $21.00 &c."15 (Fig. 15). Gold-rush prices were

high, and Grant was on a normal salary. It is a tribute to his

dedication that he borrowed money to complete the work he felt

necessary and promised to pay it back himself if the

church did not consider it a worthwhile investment.16

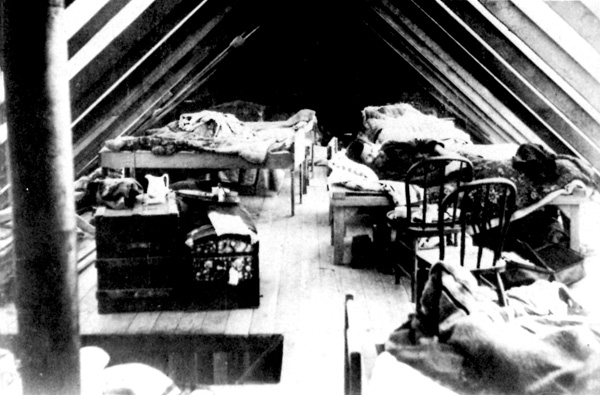

14 Hotel Dormitory. Two men to a bunk of split slabs and blankets

that smelled like axle grease.

(Sinclair Papers.)

|

15 The congregation at a church service in the spring of 1898.

Note Grant's "manse" in the background on the left, the tent

church on the right, and the bell and scaffold in between.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

Grant was finding little support among the

Klondikers. Earlier, on his way up the trail, he had commented on their

disinterest in the establishment of a church. In the Klondike "Gold is

God" recalled another man looking back on his experiences,17

and Grant found it was a vicious competitor. On 28 February he wrote to

Robertson, "I tried to conduct services at bunk houses along the way but

with little success."18 In these canvas or poorly chinked log

houses, two or three men squeezed on a single bunk of split slabs to

restoke for the day ahead19 (Fig. 14). They slept in shifts,

mindless of the stench and discomfort in their push north to the

gold-fields. "Most of the people work on the Sabbath," continued Grant,

"and it is difficult to interest them in Christian work. A man requires

much of the grace of God to sustain him in the midst of difficulties of

exposure and all such like, perhaps when we get down to work it will be

easier."20 But the first three services held in the new "St.

Andrew's Manse" in Bennett attracted only 30 people of varying

denominations. They "were comfortably seated on logs laid across blocks

of wood, and the logs were up held and stored with my blankets and

sleeping bag under them."21 Still, the collection of $5.00

did little to finance the construction of the building — a measure

traditionally used to evaluate the success of the work.

A subscription fund for the new St. Andrew's

Presbyterian Church, Lake Bennett, had nevertheless been started, and by

29 March, Grant was able to report, "so far as I have gone with the

Manse and Church everything is paid for." This may have satisfied

readers at home, but Grant himself was much less certain about the

venture. "I am sure that short of my medical mission work the manse . .

. would not have been an accomplished fact," he wrote. In the brutal,

competitive Klondike situation, Grant applied his practical talents as

a medical doctor to yield the slim margin he obviously felt was

essential for continuation. "I got a number to subscribe small amounts

and then having had occasion to treat a great many patients (some days

as many as 15) when asked my fee, asked a subscription."22

Still, the mission at Bennett, the first of a series in Canadian

territory, was in operation by March 1898.

|