|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 24

Second Empire Style in Canadian Architecture

by Christina Cameron and Janet Wright

Illustrations and Legends

61

Long's Hotel (now Prince of Wales Hotel)

6 Picton Street, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario

Constructed: 1883-85

Material: Brick

By the 1870s Niagara-on-the-Lake had lost its position as a prominent

commercial and political centre and had assumed its present role as a

tranquil resort town. With the arrival of the tourist many new hotels

had to be built in the 1870s and 1880s and of course most were

designed in the popular Second Empire fashion. Long's Hotel, later

known as Niagara House, the Arlington Hotel and finally as the Prince of

Wales Hotel, was built for William Long. According to a late-19th-century

tourist brochure it "enjoyed a well earned reputation for

first class service, at moderate prices, . . Large airy rooms and the

best of board can be obtained here for $7 a week and upwards." A modest

but respectable resort hotel, it could be described as ranking midway

between the Windsor Hotel in Montreal (Fig. 60) and the Yale Hotel in

Vancouver (Fig. 62) on the quality scale for hotel accommodation.

(Prince of Wales Hotel, Niagara-on-the-Lake.)

|

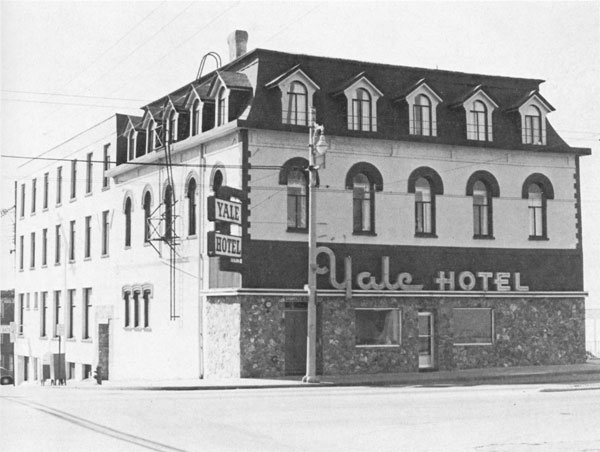

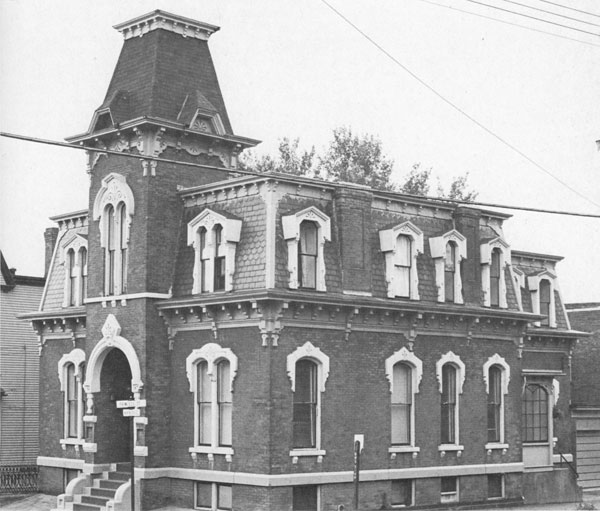

62

Colonial Hotel (now Yale Hotel)

1300 Granville Street, Vancouver, British Columbia

Constructed: 1888-89

Material: Brick

The Colonial Hotel, known as the Yale Hotel since 1907, would never have

had a reputation as one of Vancouver's fashionable inns. Situated in the

industrialized False Creek area in the working class neighbourhood of

Yaletown, chiefly populated by Canadian Pacific Railway employees from

the nearby train yards, it provided low-priced accommodation and became

well known as the centre of the notorious Yaletown nightilfe.

This plain blockish design punctuated by round-headed windows was poor

cousin to the posh, palatial Second Empire hotels like the Windsor Hotel

in Montreal (Fig. 60); yet the survival of the mansard roof indicates a

direct stylistic descendency. Undistinguished mansarded hotels like the

Yale could have been found with remarkable consistency in any number of

cities and towns across the country until the end of the 19th century.

The mansard roof became so closely associated with hotel accommodation

that this form survived well beyond the heyday of the Second Empire

style.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

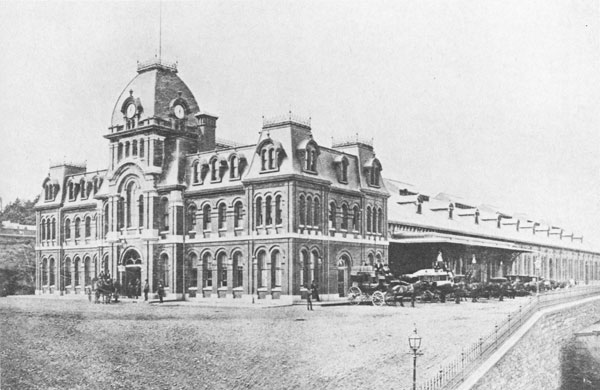

63

North Street Terminal, Intercolonial Railway

North Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Constructed: 1874-77 Destroyed: 1917

Architect: Railway Department, Department of Public Works

Material: Brick

Contrary to the general policy of the Intercolonial Railway to build

economically, the North Street terminal featured the expensive Second

Empire style. Because the railway station provided the visitor with his

first impression of a city, it was felt that a major urban centre such

as Halifax required a building appropriate to its status. This symbolic

role was observed in an 1897 publication: "Supposing one is to arrive

in the city by train, he is at once impressed with the idea that he has

reached an important terminal point, for he finds himself in one of the

finest depots ... east of Boston."

Prominent local builder Henry Peters received the contract to build the

main body of the station. The mansard roof was prefabricated in

Philadelphia by Clarke, Reeves and Company, one of several American

firms which mass-produced cast-iron architectural elements. The North

Street terminal was destroyed in the Halifax explosion of 1917.

(W.H. Howard, Halifax of Today: An Illustrated Souvenir of the

Queen's Diamond Jubilee, 1837-97 [Halifax: W.H. Howard, 1897],

n.p.)

|

64

William Bell Organ Factory

Carden Street, Guelph, Ontario

Constructed: 1881

Material: Yellow brick

Suited to its utilitarian function, the façade of the William Bell Organ

Factory has reduced the grid system of the Second Empire style to a

series of simple horizontal and vertical bands applied to a flat,

unbroken wall plane. Above the cornice, however, this undistinguished

block has been dressed up — patterned shingles, iron cresting,

flagpoles, and corner clock tower — giving it an air of picturesque

gaiety which disguises the functional design below.

The William Bell Organ Company, later to become the Bell Organ Company,

was in business from 1865 to 1930 and was said to have been the largest

reed organ company in the British Empire with branch offices in London,

England and South Africa. Although some of the original walls of the

Guelph factory are still standing much of the building was destroyed in

a fire of 1946 and in another of 1975.

(Historical Atlas Publishing Co., Historical Atlas of Wellington

County [reprint ed. of 1906, Wellington County: Corporation of the

County of Wellington, 1972], p. 14.)

|

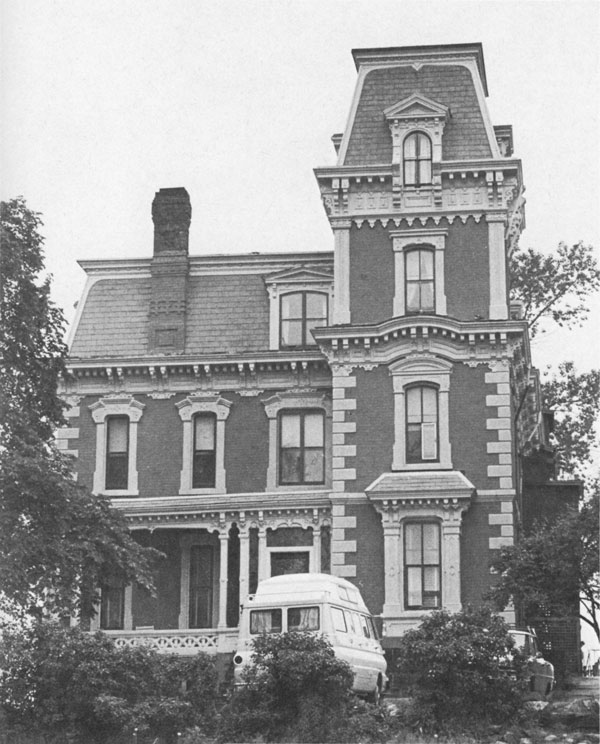

65

Chinic Warehouse

47 Dalhousie Street, Quebec, Quebec

Constructed: 1871

Architect: Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy

Material: Brick

Seven years before the opening of Dalhousie Street, the group of shops

standing on this site was demolished to make way for this large

warehouse. As originally constructed, the buff firebrick building had an

eight-bay façade surmounted by a mansard roof. A firewall projected

above the roofline and divided the building into two separate sections.

The overall massing of elements had considerable solidity in contrast

to the delicate stone trim. About 1923, the two western bays were raised

three storeys and at a later date two of the doorways were enlarged.

Unfortunately these alterations have undermined the unity of the

design.

The Chinic Warehouse was designed by J.F. Peachy, the Quebec architect

who specialized in mansard roofs, and built by master joiner Isaac

Dorion and master mason Pierre Châteauvert. The building was erected by

the Compagnie Richelieu which immediately leased one section to dry

goods merchant George Alford and the other section to Chinic and

Beaudet, one of the oldest hardware companies in the country which began

business under the name F.X. Methot.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

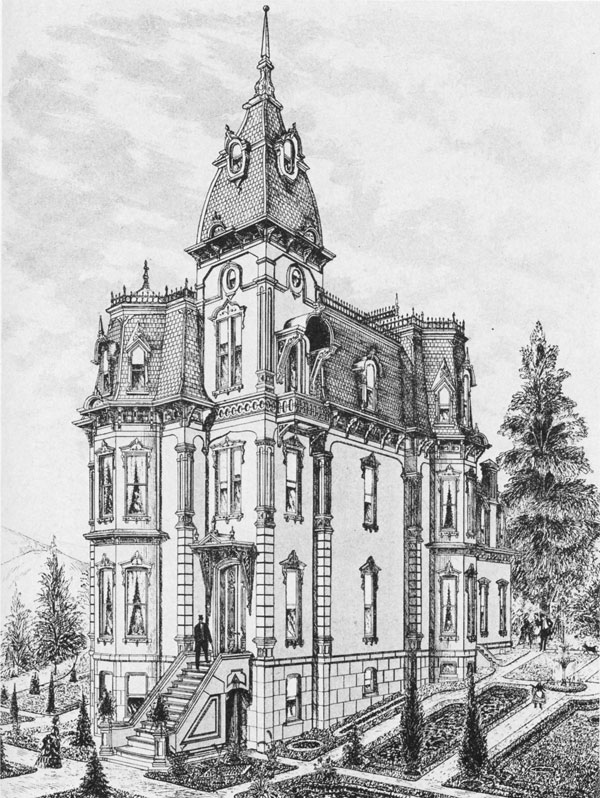

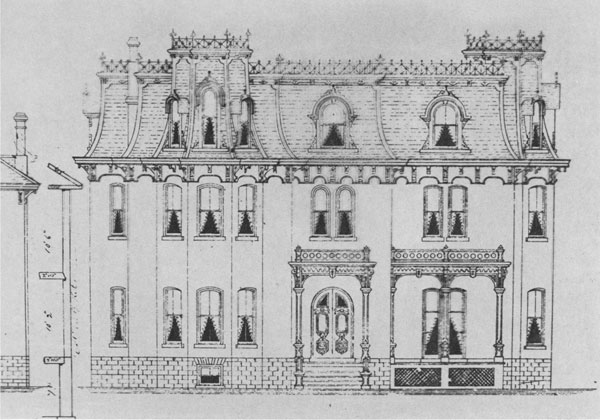

66

Design for a Villa, Mount Royal, Montreal, Quebec

Published: 1875

Architect: Gilbert Bostwick Croft

The architectural pattern book played an essential role in the rapid

dissemination of the Second Empire style across the United States and

Canada. Some of the most popular and influential of these publications

were authored by the American architect, Gilbert Bostwick Croft of

Saratoga Springs, New York. Although Croft would have been well known

in New York state for a number of mansarded designs for public,

commercial and residential building, it was his three publications

entitled Model Suburban Architecture of 1870, Original Designs

for Entrance Doors of 1871 and Progressive American

Architecture of 1875 that earned him widespread renown.

Although these books featured a wide range of styles the dominant

thrust was Second Empire. This illustration of "a stately and imposing

Villa" in Montreal was typical of Croft's extremely ornate and

flamboyant style which strove for, as Croft himself describes, "that

picturesque variety of skyline, depth of shadow, and sweet repose so

charming in an architectural conception."

In Canada, Croft's work was known in Montreal and in Saint John, New

Brunswick, where he opened a successful branch office in 1877 (Fig. 84);

however, the indirect influence of his pattern books on other architects

and builders was probably much more widespread. Although it is

impossible to determine the extent of this influence without further

study, suburban villas such as those illustrated in Belleville, Ontario

(Figs. 71, 72) and in Madoc (Fig. 68) bear a strong resemblance to the

Croft style.

(Gilbert Bostwick Croft, Progressive American

Architecture [New York; Orange Judd and Company (1875)], Pl.

40.)

|

67

405 Broad Street West, Dunnville, Ontario

Constructed: 1889

Material: Brick

Although constructed in 1889 at a time when the popularity of the Second

Empire style was declining, the design of this suburban residence, with

its symmetrical plan accented by a central projecting frontispiece and

the convex mansard roof enlivened by a broken silhouette, patterned

shingles and iron cresting, reveals little change in Second Empire

domestic architecture as it had developed in Ontario nearly 20 years

earlier. It was built for dry goods merchant Donald McDonald and, with

the exception of a rear addition of 1940 designed by Frances Brown, the

building has been altered little over the years.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

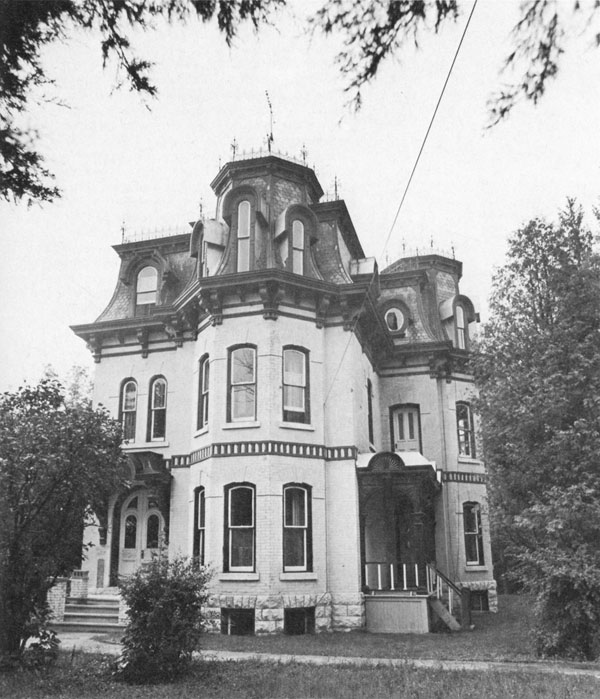

68

John C. Dale House

195 Elgin Street, Madoc, Ontario

Material: Brick

Like so many grand Second Empire mansions the palatial character of the

Dale House has been greatly enhanced by its imposing site on top of a

hill and its twelve acres of landscaped garden, complete with orchards,

a walkway through pine trees, and a bridal path. According to local

research the Dale House was built for the owner of a local private bank,

John C. Dale, between 1904 and 1910. However, a stylistic comparison

with two other Second Empire residences in the area, namely Glanmore

(Fig. 71) and 201 Charles Street (Fig. 72) both located in nearby

Belleville, would suggest an earlier date for this building. Many

similarities — the massing, the arrangement of bay windows and

verandahs, the grouping and proportions of the dormer windows, the

curved profile of the mansard roof, and the decorative details of the

cornice, window surrounds and doorway — lead one to suspect that

the Dale House dates from the 1880s, contemporary with the Belleville

examples. It may even be the work of the same architect, Thomas

Hanley.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

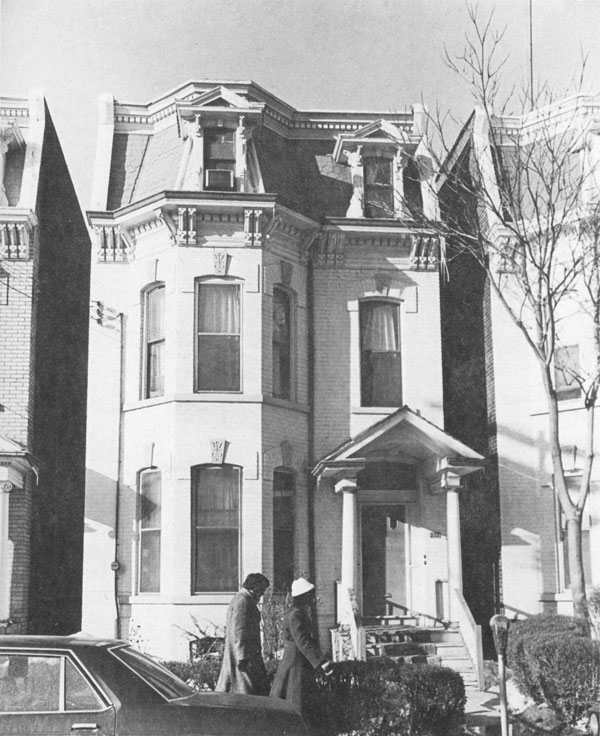

69

Lorne Hall

3 Meredith Crescent, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1876

Material: Brick

This grand suburban villa was one of the early homes to be erected in

the fashionable Rosedale area. Its first resident was prominent Toronto

businessman, William Davies, who founded a meat-packing business which

was to become Canada Packers in 1927. It was christened Lorne Hall by

William Perkins Bull who resided here from 1906 to 1943.

The design of this house can be compared in many respects to the design

for Government House (Fig. 14) by Henry Langley. Although Lorne Hall is

on a more modest scale, both are characterized by a symmetrical

composition with a centrally placed tower. An even closer parallel can

be established in a comparison between the design and location of the

porches. Both display porches on the main entrance and a longer verandah

at the side; both are surmounted by balustrades and articulated by the

unusual arch motif with rounded corners joined by a slightly raised

lintel. These similarities might be the result of an attempt to imitate

the prestigious Government House or perhaps an indication of a common

architect.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

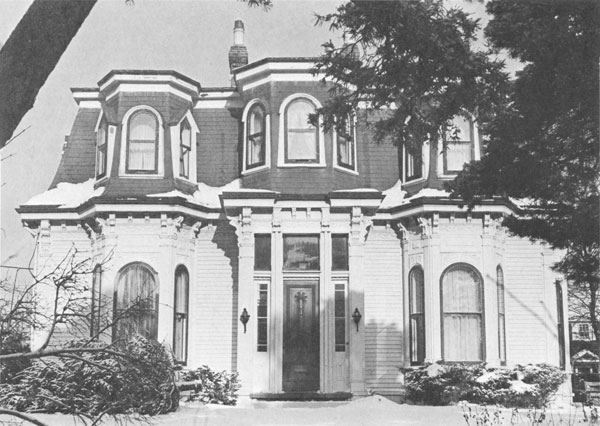

70

Fontbonne Hall

534 Queens Avenue, London, Ontario

Constructed: 1878

Material: Brick

Queens Avenue was London's residential showplace of the 1870s and

Fontbonne Hall was one of its finest architectural achievements. Built for

William Spencer, president of the newly amalgamated London Oil and

Refining Company, it is an impressive monument to the new wealth

generated by the oil discovery at Petrolia in 1861. The design maintains

the symmetrical composition characteristic of public building, but the

detailing, with its ornate bracketed cornice and large two-storey bay

windows accented by slender stone columns, has been handled with a

lighter and more festive touch. The treatment of the roof, distinctive

for its lively play of planes and curved shapes, adds an attractive

finishing touch. The porch and large brick wing are recent

additions.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

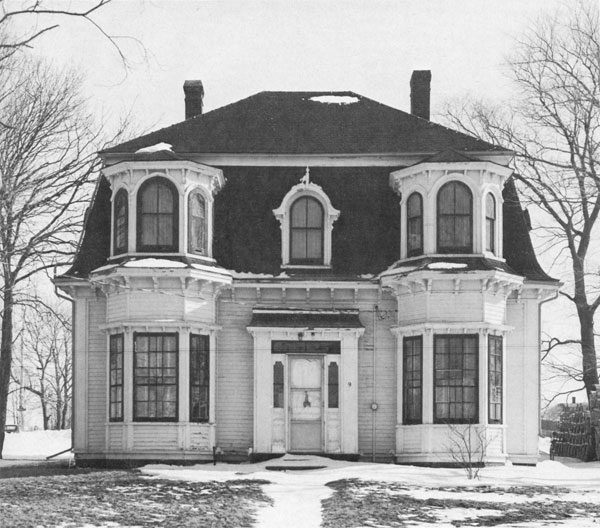

71

Architectural Drawing for Glanmore

257 Bridge Street, Belleville, Ontario

Constructed: 1882-83

Architect: Thomas Hanley

Material: Brick

The Second Empire style, when applied to domestic architecture, often

takes on a more refined and elegant air than the robust massing and

forms characteristic of public building. Glanmore, originally built for

wealthy banker and financier, John Philpot Curran Phillips, and now

housing the Hastings County Museum, offers one of Ontario's most

elaborate examples of this taste. Features such as the asymmetrical

massing, the gentle concave curve of the roof, the delicate woodwork of

the dormer windows, and the bracketed cornice with scalloped frieze

accenting the pattern of window openings below, create an appearance of

picturesque elegance — a quality strongly advocated for domestic

building in American architectural pattern books.

The designer, Thomas Hanley, is listed in the Belleville directories as

a carpenter, builder and architect from 1878 to 1902. Nothing is yet

known of his origins or training; however, judging from his design for

Glanmore he was either an architect of considerable skill or a very

clever copyist of contemporary pattern books.

(Hastings County Museum.)

|

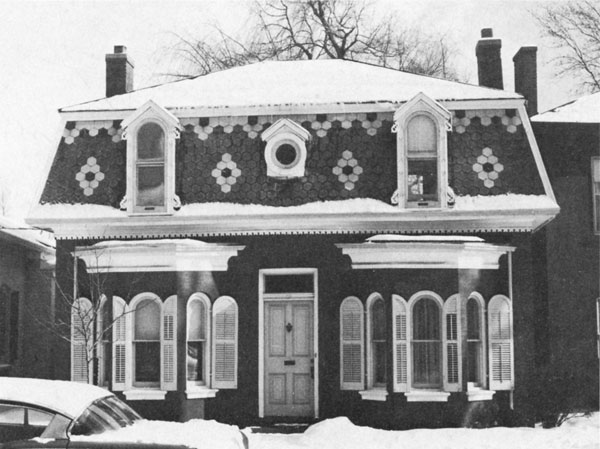

72

201 Charles Street, Belleville, Ontario

Constructed: ca. 1879

Material: Brick

Belleville was well endowed with a number of fine Second Empire houses,

probably the legacy of local architect/builder Thomas Hanley. Although

Glanmore (Fig. 71) is the only documented example of his work, 201

Charles Street, built for local physican Dr. Potts and first listed in

the Belleville city directories in 1879-80, bears all the outward

signs of a Hanley design. Similar in plan, roof shape, arrangement of

window openings and verandahs, and almost identical in the minute

detail of the porches, in the fretted ornaments above the dormers, and

in the decoration of the upper or deck cornice, 201 Charles Street

provides an attractive companion piece to Glanmore and confirms Hanley's

position as an important designer of Second Empire domestic

architecture.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

73

William G. Perley House

415 Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ontario

Constructed: ca. 1875 Demolished

Material: Brick

The Second Empire style which dominated the Wellington streetscape was

not restricted to public and commercial building. The Perley House,

situated on the present site of the National Library and Public Archives

Building, provided a residential complement to the dignified parade of

mansarded government buildings and banks which lined Wellington Street.

Built around 1875 for William G. Perley, co-owner of the Ottawa lumber

company, Perley and Pattee, and later a member of Parliament, this

immense brick residence showed a refinement and sophistication on such

features as the porches, bay window and dormers that was unusual for

domestic buildings in Ottawa but appropriate to its location on the

most prestigious street in the new nation's capital.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

74

Wyoming

67 Queen Street, Guelph, Ontario

Constructed: 1866-67 Enlarged: ca. 1880

Material: Stone

Instead of building anew many owners of older houses gave their

residences a Second Empire up-date by adding a mansard roof. As

originally built in 1866-67 for wealthy dry goods merchant, John

Hogg, 67 Queen Street was a small one-storey building constructed of

the characteristic Guelph limestone and idyllically situated on the

crest of a hill on Queen Street in a five-acre park-like setting.

In 1880 Hogg sold the entire property to James W. Lyon, owner of the

internationally known World Publishing Company and Guelph's first

millionaire. By adding an extra storey, a mansard roof, and servants'

quarters at the rear, Lyon transformed this small cottage into a

palatial Second Empire mansion which he renamed Wyoming.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

75

Hallowell Township, Prince Edward County, Ontario

Material: Brick

This farmhouse in Hallowell Township provides a notable exception to the

generalization that Second Empire is predominantly an urban and suburban

style. Its picturesque effect comes from the asymmetrical composition

with off-centre tower and the wealth of iron cresting and carved

ornamentation. The characteristic round dormer windows and intricate

cornice brackets on this elegant residence demonstrate a sophisticated

awareness of Second Empire design that is unusual in a rural area.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

76

125 Rosemount Avenue, Weston, Ontario

Material: Brick

Today, the town of Weston has been consumed by Metropolitan Toronto as

part of the Borough of York, but houses such as 125 Rosemount Avenue

provide glimpses of the original character of the town when it was a

small, independent manufacturing centre to the northwest of Toronto.

While it is often a tendency in smaller residential buildings to reduce

the Second Empire style to the use of a mansard roof, 125 Rosemount

Avenue, despite its modest scale, reflects a sophisticated use of

Second Empire forms. The asymmetrical massing, the picturesque play of

receding wall and roof planes, and ornate dormers and verandahs recall

grand Second Empire mansions found throughout Ontario.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

77

29 West Street, Brantford, Ontario

Constructed: Post 1875

Material: Brick

This one-and-a-half storey, symmetrical design is a continuation of a

traditional building type often referred to as the "Ontario cottage";

but in this case, there has been a Second Empire update with the

addition of a mansard roof and bay windows. It is obviously the work of

a local builder as is indicated by the unsophisticated handling of the

top-heavy mansard roof and the rather stiff interpretation of the

characteristic round dormer window. The lively colour scheme of

patterned shingles captures a delightful sense of the picturesque.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

78

332-344 Rubidge Street, Peterborough, Ontario

Constructed: 1884-85

Material: Brick

This residential row in Peterborough represents the height of Second

Empire fashion in terrace housing. By uniting the individual units into

one compositional scheme of balanced projecting pavilions, the architect

has avoided the monotonous repetition of identical units that so often

characterizes row housing and has captured that sense of monumentality

reminiscent of grand public building in the Second Empire vein.

It was built for George Cox, a wealthy insurance baron and entrepreneur

from Peterborough as an investment property. Although the architect has

not yet been documented, its design is identical to another terrace

block in Winnipeg constructed in 1882 by the firm of architects, Wilmot

and Stewart, a fact which suggests the use of these same architects or

at least the same plans.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

79

119-133 Spruce Street, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1887

Material: Brick

Although by 1887 the Second Empire style was well past the height of

fashion, the mansard roof did not entirely disappear from use. Its

appeal was both practical and aesthetic for as seen in this modest

terrace unit in Toronto the mansard roof provided two full storeys but

with an added touch of the picturesque in its steep front slope

decorated with dormer windows, patterned shingles, and iron cresting. By

this device, the builder avoided the monotonous form of the alternative

two-storey box with a flat roof.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

80

322 Dundas Street East, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1886-87

Material: Brick

This house forms one of a series of almost identical buildings on the

north side of Dundas Street, It is located on the fringes of the once

fashionable Sherbourne Street and, despite the narrowness of the lot,

the insistence on a single detached unit instead of a less expensive row

house indicates an attempt to maintain a prestigious look to the

neighbourhood. The heavy bracketed cornice and fancy dormers capture

some of the richness of the Second Empire style but the narrowness of

the façade and the height of each storey produce an elongated and

pinched appearance.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

81

Farmhouse

Maitland, Hants County, Nova Scotia

Material: Wood

This small farmhouse represents a blending of the Second Empire style

with a well-established Maritime building tradition. The mansard roof

and the taste for richer surface ornamentation are drawn from Second

Empire design; however, these elements only thinly disguise the familiar

compact, squarely proportioned building with symmetrical façade

decorated with doric pilasters and segmental pediments and shelves,

characteristic of an older Maritime building type in the classical

vernacular tradition. The projecting frontispiece imitates the pavilion

massing of the Second Empire style but, again, this form, minus the

mansard roof, was already well entrenched in the Maritime building

vocabulary.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

82

Quinniapiac

25 Winter Avenue, Saint John's, Newfoundland

Constructed: ca: 1885

Material: Wood

Quinniapiac imparts a distinctly Maritime flavour to the Second Empire

style due to its use of clapboard and its rich application of

intricately carved wood ornamentation. The large triple-paned dormer

motif is a characteristic feature of the Maritimes. When the dormers are

seen in conjunction with the bay windows on the ground floor an effect

similar to the projecting pavilions of high-style Second Empire is

created. As originally built for Prescott Emerson, a judge of the

Newfoundland Supreme Court, Quinniapiac had a tower and conservatory;

however, both were removed in the early years of the 20th century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

83

49 Rennies Mill Road, Saint John's, Newfoundland

Constructed: 1885

Material: Brick

This building was welcomed with enthusiastic praise by the Saint John's

Evening Telegram on March 23, 1885, which described it as "the

magnificent residence which has just been erected by Mr. (Alexander)

Marshall in that fasionable suburb locality known as Rennies Mill Road.

It stands as a monument of success in business, an ornament to the

neighbourhood and a most convincing proof of the mechanical skill and

ingenuity of our native workmen." This fine residence would have been

particularly outstanding since it was built of "Boston" and "Bangor"

brick instead of the usual wood; yet, despite the use of these atypical

materials, a distinct Maritime appearance has been retained. The

delicate and whimsical treatment of the stonework and the colorful

panels of white enamelled brick under the eaves recall the intricacy and

fluidity of detail common to Maritime building in wood.

This same article identified John Score, a local man, as the builder. No

mention of an architect was made; however, although it was not unusual

for builders to provide their own designs, the sophistication of this

building would suggest the work of a yet unknown architect.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

84

99 Wentworth Street, Saint John, New Brunswick

Constructed: 1877-78

Architects: Gilbert Bostwick Croft and F.T. Camp

Material: Brick

The firm of Croft and Camp from Saratoga Springs, New York, opened a

Saint John office in 1877, probably in order to capitalize on the

building boom created by the great fire earlier that year. Croft was

already well known for his numerous public and private commissions

primarily in the state of New York and for several publications of his

architectural designs (Fig. 66). With these credentials, his firm was

quickly accepted by the Saint John community.

The house on Wentworth Street, built for local druggist A. Chipman

Smith, is one of the many buildings designed by this firm in Saint John.

A contemporary report on the construction in the Daily Telegraph

describes this "Handsome French Cottage" as having "a graceful,

well-proportioned tower that will rise to an elevation of seventeen feet

above the cresting line of the mansard roof, with flowing frieze and

angular pediments which will, with the bold chimney tops, give the

entire structure a most graceful and pleasing outline." The building was

also praised for its modern conveniences in heating and plumbing,

providing "an interesting and suggestive model in both beauty and

convenience."

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

85

354 Main Street, Saint John, New Brunswick

Constructed: 1875

Material: Brick

Perched high on a hill commanding a spectacular view over Saint John,

this palatial mansion certainly merits its name "the Castle." Although

the use of brick, the large scale, and the asymmetrical massing with

corner tower are more akin to Second Empire residential building in

Ontario, the characteristic Maritime taste for abundant surface detail

is clearly evident. In fact, this quality as seen in features such as

the elaborate cornice molding with finely carved scroll brackets and

panelled frieze fringed with fretted ornaments, the delicately incised

window surrounds capped with the broken curve of the entablature, and

the lightly carved detail of the veranda, has rarely been expressed in

such an exuberant and lavish manner.

"The Castle" was built about 1875 for Count Robert Visart De

Bury of Belgium who, having married into the well-known

Simonds family of Saint John, moved to Portland (now a part of

Saint John) in 1873 where he served for many years as Belgian

Consul to New Brunswick and Consular Agent for France at Saint

John and was, for a number of years, a member of the Portland

Town Council.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

86

High Street, Souris East, Prince Edward Island

Constructed: Before 1880

Material: Wood

A common design characteristic of small domestic building in the Second

Empire style which appears most frequently in the Maritimes is the

tendency of the mansard roof to dominate the overall design. The house

at Souris East, built for Dr. P.A. Mcintyre, Lieutenant-Governor of

Prince Edward Island from 1899 to 1904, offers a good example of this

tendency. The unusually steep upper roof slopes produce a very high

mansard roof that overpowers the supporting walls.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

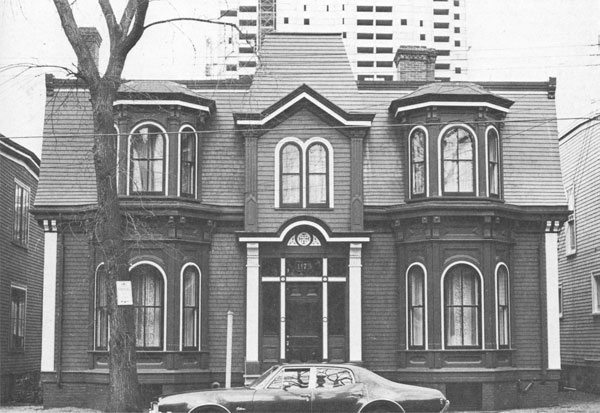

87

1173 South Park Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Constructed: Between 1888 and 1895

Material: Wood

At the end of the 19th century the recovery of the Halifax economy

after two decades of stagnation encouraged a rapid growth in the city's

population. The house at 1173 South Park Street is a typical product of

the extensive suburban development intended to meet the housing needs

of the expanding community. Despite the waning popularity of the Second

Empire style at this time, the use of the mansard roof and the regional

feature of the bay dormer over the bay window indicate the persistent

hold of this style on building in the Atlantic provinces.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

88

37 Mecklenburg Street, Saint John, New Brunswick

Constructed: between 1877 and 1882

Material: Wood

The great fire of 1877 devastated much of Saint John at the height of

the Second Empire craze. As a result, much of the consequent rebuilding

reflected this current architectural fashion. Although many chose to

rebuild in more fire-resistant brick, the house at 37 Mecklenburg,

constructed for the Eaton family to replace the home they had lost in

the fire, was fairly typical of residential building in the post-fire

period. This one-and-a-half storey building with double bay windows

capped by triple-paned bay dormers repeats a familiar Maritime type. The

use of the oval dormers, a feature usually associated with large public

buildings, adds a distinctive touch.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

89

767 Brunswick Street, Fredericton, New Brunswick

Constructed: Post 1882

Material: Wood

Lined with gracious Victorian homes set amid tall elm trees, the

Brunswick streetscape captures the dignified atmosphere of a

19th-century residential avenue. The house at 767 Brunswick Street

provides one of its finest architectural features. The use of a narrower

two-bay façade as opposed to a symmetrical three-bay façade is more

characteristic of urban building where the narrower city lot requires a

more compact plan. As a result the design has a much stronger vertical

emphasis which is accentuated by the tall mansard roof and by the

upward thrust of the typical Maritime feature, the double bay window

with a triple paned bay dormer. An accurate date of construction has not

yet been determined but the house was probably built soon after the

purchase of the lot by Alexander Sterling in 1882.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

90

A.R. Dickey House

169 Victoria Street East, Amherst, Nova Scotia

Material: Wood

Arthur Rupert Dickey (1857-1900), the son of R.B. Dickey, a father of

Confederation, was a noted Nova Scotian lawyer, a member of Parliament

for Cumberland County from 1888 to 1896, and a cabinet minister from

1894 to 1896. His residence in Amherst is of modest size but handsomely

executed in the suitably fashionable Second Empire style. The dormer

design with sides that cut through the eaves line of the roof is a

feature frequently found in the Maritimes.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

|