|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 24

Second Empire Style in Canadian Architecture

by Christina Cameron and Janet Wright

Illustrations and Legends

91

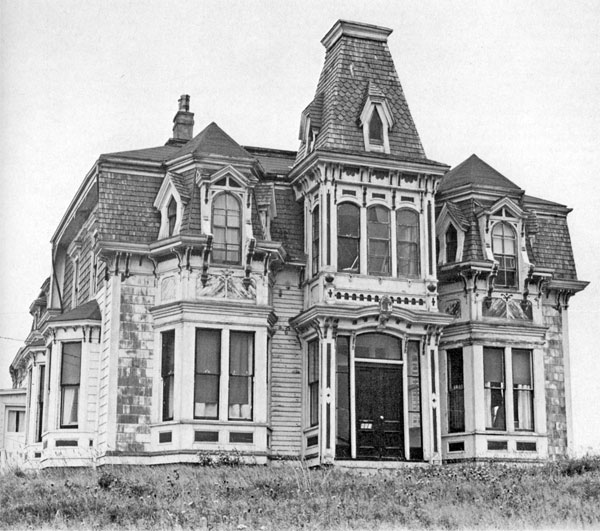

917 Loch Lomond Road, Saint John, New Brunswick

Material: Wood

This charming residence, now situated in the outskirts of Saint John,

may be modest in size but is certainly not modest in dress. Rarely have

the decorative possibilities of wood been handled with such variety and

exuberance. The brightly painted carved details which have been

liberally sprinkled over the building and the contrasting patterns of

the wood shingles and horizontal and diagonal planking produce an

exceptionally fanciful version of the Second Empire style. Typical of

the Maritimes are the dormer windows which cut through the eaves line

and are edged by giant consoles.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

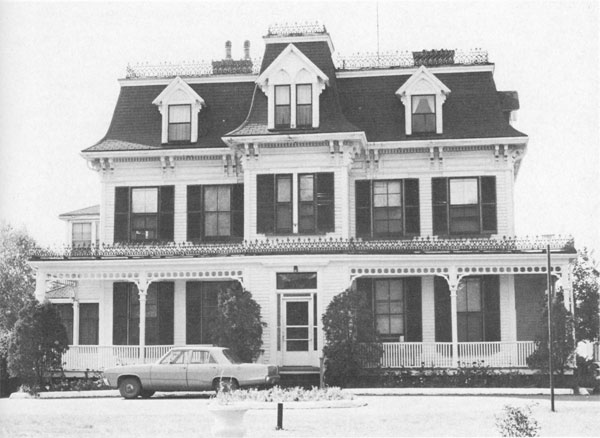

92

Birchwood

35 Longworth Avenue, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

Constructed: 1876

Material: Wood

According to the Charlottetown Examiner of June 2, 1877 the plans

for Birchwood were drawn up by the owner, Lemuel Cambridge Owen, an

important shipowner and merchant in the community. His house shows an

awareness of Second Empire design in such features as the mansard roof,

projecting central pavilion with its mansarded tower and delicate iron

cresting that enlivens both the verandah and the roof. Yet beneath these

elements, one recognizes the compact form and broader proportions of the

earlier classicizing tradition. This conservative approach would seem to

confirm the hypothesis that an amateur architect was responsible for the

design.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

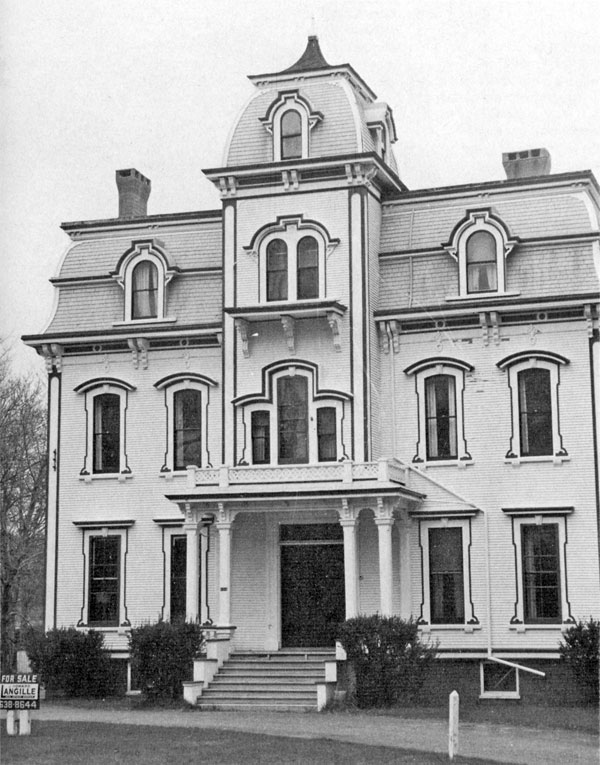

93

Queen Hotel 494 Saint George Street, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Material: Wood

Originally built as a private residence for Thomas Ritchie, the building

served as a posh boarding house until 1897 when it became a boys'

private school. In 1921 W.C. MacPherson bought the Ritchie House to

replace the original Queen Hotel which had burnt down that year. Today

it is still known as the Queen Hotel although it now operates as a

boarding home for the aged.

An unusually grand and showy residence for a small community such as

Annapolis Royal, the design reflects that characteristic Maritime taste

for minute, intricately carved wood detail in the shaped window

surrounds, cornice brackets, and delicate fretted ornaments under the

eaves. The addition of an extra cornice molding at the point where the

mansard roof changes from concave to convex curve gives the roofline a

highly individualistic appearance.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

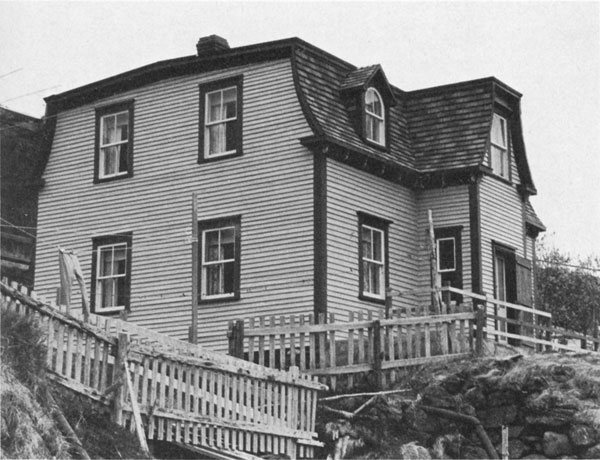

94

Ship Cove Road Burin, Burin Peninsula, Newfoundland

Material: Wood

This modest house would seem to have little in common with the sumptuous

and richly ornamented Second Empire style; yet the use of the mansard

roof links it with the more formal tradition. Typical of Newfoundland

vernacular interpretation are certain forms like the almost flat upper

portion of the mansard and the dormers which have semicircular windows

set into a gable shape. The projecting central section with flattened

tower may perhaps be a distant echo of the Second Empire pavilion.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

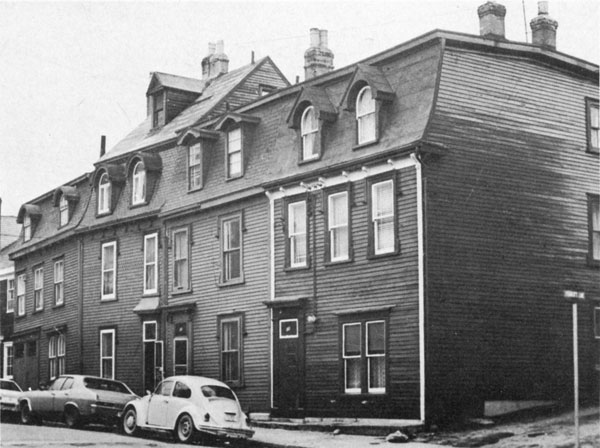

95

176-182 Gower Street, Saint John's, Newfoundland

Constructed: post 1892

Material: Wood

This type of row house, characterized by clapboard siding and mansard

roof with almost flat upper slopes, was built time and again after the

fire of 1892 which destroyed almost all of the downtown core of Saint

John's. Buildings of this nature can be found throughout the city and

form an essential part of its distinctive architectural character. This

plain, economical design is far removed from the flamboyant and

extravagant Second Empire style; however, the survival of the mansard

roof indicates the lasting mark left by this tradition.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

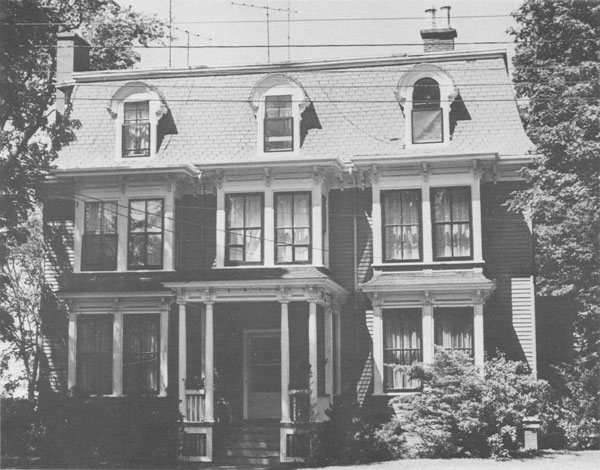

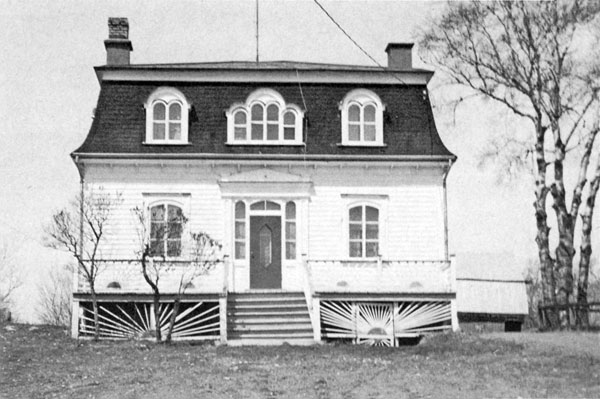

96

30 Monkstown Road, Saint John's, Newfoundland

Constructed: 1875

Architects: J. and J.T. Southcott

Material: Wood

This residential building is one of a pair of identical structures

situated side by side on the fashionable suburban street of Monkstown

Road. Both were designed by the father and son team of J. and J.T.

Southcott whose names became so closely associated with the Second

Empire style in Saint John's that it has been locally referred to as the

"Southcott style". The Monkstown Road pair are typical of the

Southcotts' Second Empire residences in the use of the bellcast mansard

roof, round-headed dormers, and two bay windows on the front. The

absence of a prominent front entrance, a product of an interior plan with

the central hallway running parallel to the main façade, is an unusual

but often repeated feature of Southcott houses.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

97

31 Lincoln Street, Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Material: Wood

In Lunenburg the mansard roof made a considerable impact although the

Second Empire style was modified by established building traditions,

imparting a distinctive local flavour to this style. The house at 31

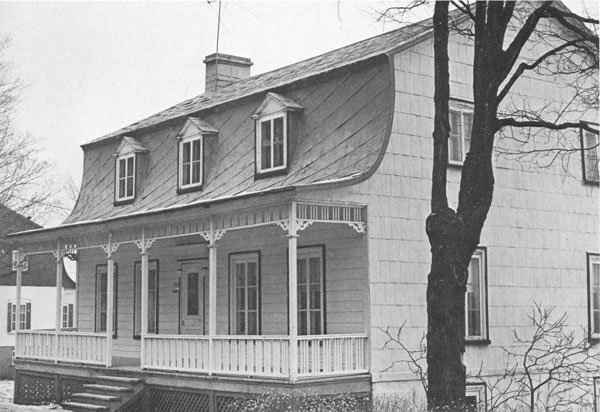

Lincoln Street, constructed of wood, symmetrical in plan and restrained

in detail is a typical example of larger domestic building of this style

in Lunenburg. The three-sectioned projecting frontispiece,

characterized by strong horizontal divisions, is unified by the

semicircular forms of the doorway and windows.

(Engineering and Architecture Branch, Department of Indian and

Northern Affairs.)

|

98

143 Queen Street, Truro, Nova Scotia

Material: Wood

As seen in an old photograph published in a late 19th-century pictorial

guide to Truro, Queen Street was lined with spacious Victorian homes

situated on ample, well-treed lots — a typical suburban environment

of the late 19th century. These residences offered a wide range of

styles of which the Second Empire style, as typified by 143 Queen

Street, was among the most popular. By Maritime standards the decoration

of 143 Queen Street is quite reserved, being restricted to light scroll

brackets under the eaves and boxed bay windows, a recurring feature of

Second Empire residences in Truro which contributes to the angular

appearance of the façade.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

99

Shaughnessy House

1923 Dorchester Street West, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1874-76

Architect: William T. Thomas

Material: Stone

Among the largest of Montreal's stately mansions, the Shaughnessy House

was originally a double dwelling built jointly for textile manufacturer

Robert Brown and Canadian Pacific Railway magnate Duncan Mcintyre. It

bears all the standard features of high-style Second Empire including

pavilion massing, bay windows, semicircular window openings, and an

ornate mansard roof with oval dormers and rich iron cresting. True to

Second Empire ideals, it enjoys a wide vista and a pleasing view over

the Saint Lawrence River valley. The use of stone, however, puts the

stamp of Quebec on this house. The design comes from William T. Thomas,

one of Montreal's most prolific architects who specialized in

fashionable residences in the Italian manner. The builders were master

builder and mason Charles Lamontagne, and master carpenter and joiner

Edward Maxwell. The house has remarkable associations with railway

history, having been occupied by such notables as William Van Horne, who

lived here from 1882 (the year he became general manager of the Canadian

Pacific Railway) until 1891, and Lord Shaughnessy who moved into the

eastern half in 1892 and later took over the entire house when he became

president of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1899.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

100

3532-3538 Sainte-Famille Street, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1872 (no. 3532); 1876 (no. 3538)

Material: Stone

Built in the 1870s by mercantile agent Charles Gagnon, these two houses

reflect the particularities of small-scale development at this period.

Gagnon began by occupying the earlier house, and moved four years later

to the second house when it was completed. Although most of

Sainte-Famille Street was developed at this time, land was owned in

small parcels; consequently, houses are generally similar, but specific

details are different. Gagnon's pair are typical of Montreal row houses

in the Second Empire vein with their façades articulated by projecting

pavilions capped by mansarded towers, their high basements serving as

full living storeys, and especially in their use of contrasting

textures of stone. Although no architect has been identified for the

design of Gagnon's houses, it is interesting to note that his next door

neighbour was architect A.G. Fowler in 1873 and then architect A.F.

Dunlop from 1874-76.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

101

661-675 Grande Allée East, Quebec, Quebec

Constructed: 1882-83

Architect: Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy

Material: Stone

This residential row on Quebec's most prestigious thoroughfare was put

up by Abraham Joseph, a prosperous merchant who occupied a splendid

residence on an adjoining site. The specifications called for work of

the best quality, including such requirements as fine bush-hammered

Deschambault stone, without veins, marks or other defects, for the

ground storey, and metal-covered roofs similar to the new construction

at the Séminaire de Québec (see text 42). Following the plans of

Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy, the architect who so favoured the Second Empire

style, the builders achieved a picturesque effect, by conservative

Quebec City standards, through the rugged masonry, bay windows,

decorative dormers and a mutlitude of brackets. Attractive details like

the segmental openings and the door and window surrounds lend coherence

to the overall design. The contractors were John O'Leary for masonry,

Joseph Garneau for carpentry and joinery, William McDonald for painting

and Zepherin Vaudry for plumbing and metalwork. When these houses were

completed, two of his sons, Andrew and Montefiore Joseph, active

partners in the business, occupied Nos. 665 and 675, residing there

until well into the 20th century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

102

3837-3893 de Bullion Street, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1876-81

Material: Brick

This long terrace, put up on what used to be called Cadieux Street,

occupied most of the city block between Napoleon and Roy streets.

Development began in 1876 and houses were gradually added until 1881

when the terrace contained eighteen identical structures. Unlike some of

the grand stone terraces in Montreal, this row was built on an economic

scale, only one storey in height with inexpensive brick. Token reference

to Second Empire influence is given in the slight wall projection on

each unit that suggests pavilion massing, the shallow mansard-roofed

towers with some iron cresting still intact, and the semicircular

dormers. The terrace was intended to provide housing for modest income

groups as a random sample of the 1881 street directory confirms. The

occupants at that time included merchants, clerks, stenographers,

bookkeepers, insurance agents and grocers.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

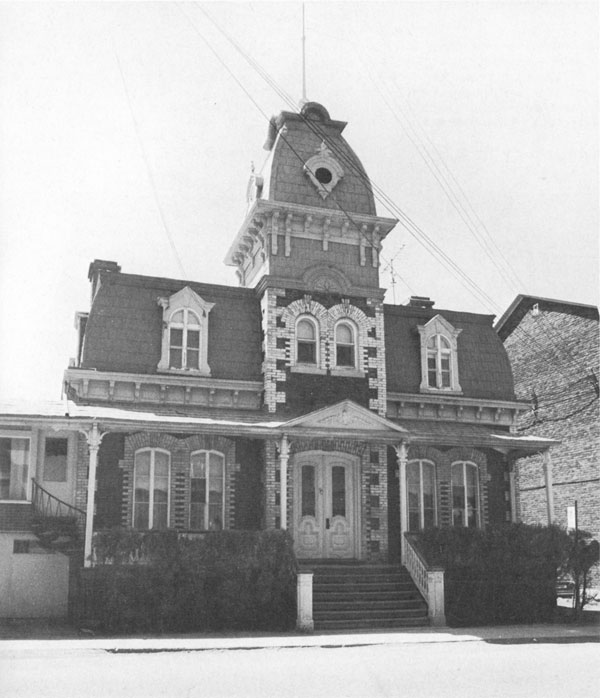

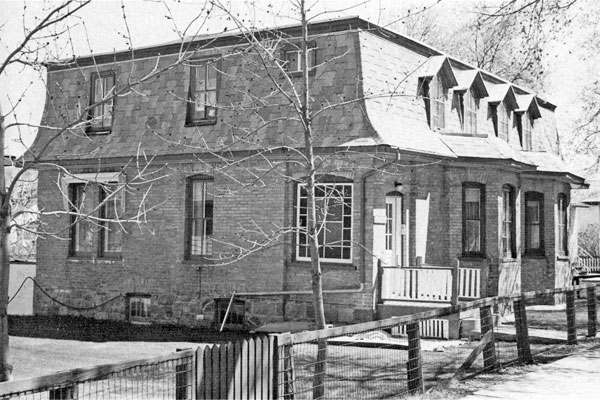

103

28 Guénette Street, Lévis, Quebec

Constructed: Before 1889

Material: Brick

This imposing dwelling is just one of several substantial

mansard-roofed residences recorded by the Canadian Inventory of Historic

Building in Lévis, a concentration that reflects the growth in size and

stature of this urban centre in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Little is known about the house except that building contractor Joseph

Paquet lived here from at least 1889 until after 1915. Whether Paquet

was the original owner and/or builder is unknown. While the walls are

handled in a relatively simple manner, enlivened mainly by the use of

different colours of brick (a favorite device of Gothic Revival

designers), the mansard roof ranks among the sophisticated

characteristics of Second Empire influence. The curved ribs of the main

roof are echoed by the tower, which also features delicate round windows

similar to models illustrated in American pattern books.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

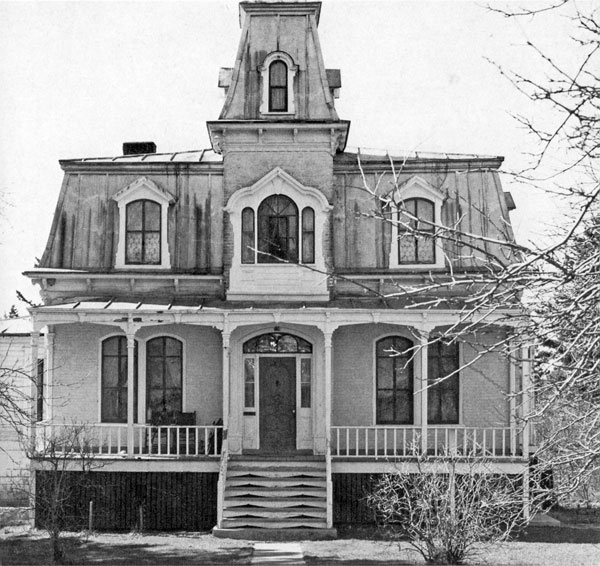

104

118 Fraser Street, Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec

Constructed: ca. 1880

Material: Brick

This attractive suburban villa in the community of Rivèere-du Loup,

formerly known as Fraserville, proves that Second Empire influence

extended far beyond Canada's principal cities. Though the wall surfaces

are flat and the ornamentation timid, the overall design is appealing

for its play of semicircular and segmental forms. A fine touch is the

graceful flare of the ribs on the main roof and tower.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

105

52 Vachon Boulevard, Sainte-Marie-de-Beauce, Quebec

Constructed: 1885

Material: Wood

Shortly after it blossomed in major urban centres, Second Empire reached

the more remote communities in Canada like the Beauce region south of

Quebec City. This residence at Sainte Marie-de-Beauce reflects a

regional preference for frame and clapboard construction, but in design,

follows the new Second Empire craze. The sophistication of certain

details — the convex ribbing on the mansarded tower and the round

decorative windows — suggests the influence of pattern books from

the nearby northern United States. The architect has not yet been

identified. The house was built for a local merchant, Gédéon Beaucher

dit Morency, who sold both house and contents two years later to

notary Georges Théberge when he left Saint-Marie-de-Beauce for

Montreal.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

106

7214 Royale Avenue, Château Richer, Quebec

Constructed: ca. 1880

Material: Wood

In its main form, this house represents the culmination of the

vernacular tradition in rural Quebec, the result of slow evolution over

two centuries. Typical features include the one-and-a-half storey

height, raised basement, full-length verandah, symmetrical design of

the façade and classicizing doorway trim. What is new is the mansard

roof. Permitting full use of the attic storey, it was probably adopted

for its practical advantage rather than for any connection with

fashionable Second Empire style. Characteristic of the Quebec

interpretation of the two-sided mansard are the marked rise in the upper

slope and the bellcast eaves or larmier which has such a

pronounced extension that it provides shelter for the verandah.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

107

2 Saint-Joseph Boulevard, Charlesbourg, Quebec

Constructed: ca. 1885

Material: Wood

If one disregards the mansard roof, this building represents the fully

evolved Quebec farm house with its raised basement, symmetrical

arrangement of door and windows, and full-length verandah, in this

instance sweeping around each side of the house. What is unusual in the

context of the traditional rural house in Quebec is the mansard roof.

This particular kind of mansard roof — four-sided with steep upper

slopes — appeared suddenly in Quebec in the latter decades of the

19th century. A characteristic and attractive Quebec feature is the

uninterrupted bellcast curve at the eaves of each slope which flares out

to form the roof of the verandah.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

108

3525-3527 Royale Avenue, Giffard, Quebec

Constructed: ca. 1880

Material: Stone

This dwelling representing a rare combination of the so-called Quebec

artisan home with Second Empire features, indicates the extent to which

the new style penetrated vernacular building in Quebec. Usually located

on a sloping piece of property, the artisan house is characterized by

having the main living quarters on the upper storey and a workshop or

commercial area on the ground storey. Access to the upper storey is

provided in this case by a winding metal staircase that leads to a

full-length balcony. Although this type was usually found on the Beaupré

coast east of Quebec City, it rarely appeared with a fashionable mansard

roof. The fine quality of the rough-faced masonry with smooth ashlar

trim is a tribute to the continuing fine tradition of stone construction

in Quebec.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

109

Lismore

215 South Street, Cowansville, Quebec

Constructed: 1881

Material: Brick

The Eastern Townships saw the construction of a number of fine

high-style Second Empire residences during the 1870s and 1880s and

Lismore, built for Cowansville mill-owner George K. Nesbitt, is its most

outstanding surviving example. The modifying influence of a strong

vernacular building tradition, which is so often evident in Quebec's

domestic architecture of the Second Empire mode, is completely absent in

this flamboyant, thoroughly up-to-date design. The picturesque quality

of light and shadow created by varied wall planes, pavilioned and

towered roofline, textured surfaces and abundant wood and iron

ornamentation, has rarely been so fully and unabashedly exploited. Lismore

remained in the Nesbitt family until the 1950s when it was donated to

the Anglican diocese of Montreal. Since 1957 it has served as a home for

the aged known as the Nesbitt Anglican Residence.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

110

Avenue de Gaspé, Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Quebec

Constructed: ca. 1890

Architect: Charles Bernier

Material: Wood

This modest wooden house is one of several in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli which

reflect the renewed popularity of the mansard roof in rural Quebec.

There are other dwellings of similar design on neighbouring lots in this

village, renowned for its woodworking virtuosity. This example displays

a suppleness of form and carved decoration, especially in the treatment

of the doorway and the graceful dormer windows. The raised basement and

full-length gallery are familiar features that belong to the rural

house tradition in Quebec.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

111

168 Rutherford Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1881-82

Architect: L.A. Desy

Material: Brick

This is one of a pair of similar dwellings erected for partners

Alexander Brown and Thomas Rutherford on the banks of the Red River

adjacent to their flourishing lumber mills at Point Douglas. No. 168

Rutherford Street was built for Rutherford, No. 170 for Brown, with each

man acting as his own contractor. Although neither house is enormous by

Second Empire standards, being one-and-a-half storeys high and three

bays wide, they nevertheless attain a sense of style through the use of

the projecting central section with mansarded tower and the elliptical

doorway. A contemporary account insists that they "may be classed among

the handsomest buildings." While one newspaper account cites "E. Desy"

as the architect, the only one residing in Winnipeg in the early 1880s

was L.A. Desy, architect of the Cauchon Block (known today as the Empire

Hotel).

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

112

Houlahan's Terrace

395-409 Alexander Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1883

Material: Brick

In 1883 a Winnipeg newspaper announced that "Mr. J. Houlahan,

plasterer, has built a very fine brick terrace, three stories high and

containing eight good sized houses." Houlahan's Terrace, as it came to

be known, provided decent economical accommodation for working-class

people including railroaders engaged at the nearby Canadian Pacific

Railway yards. Though accordingly simple and unadorned, Houlahan's

Terrace makes reference to the Second Empire style in its use of the

mansard roof and the rhythmic series of projecting and recessing walls

capped by alternating large and small conical dormers.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

113

W.H. Lyon House Graham Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1881 Demolished: ca. 1912

Architects: Edward McCoskrie and Joseph Greenfield

Material: Brick

The Lyon House, built for W.H. Lyon and occupied in 1883 by Dr. James

Kerr, a prominent physician who had recently emigrated from Ontario,

offers a good example of the gracious housing that was being produced

for the well-to-do in a boom-town atmosphere. Designed by architects

McCoskrie and Greenfield and built by contractors Paterson and McComb,

it is a simple but substantial brick block, dressed up with ornate roof

cresting and tall chimneys. The roof lantern, an unusual feature for

Second Empire, and the delicate verandah are later additions carried out

about 1890 for owner George Strevel under the direction of architect

George Browne.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

114

113 Princess Avenue East, Brandon, Manitoba

Constructed: ca. 1888

Material: Brick

This large yellow brick house, now subdivided into apartments, served as

a single family dwelling until the 1930s. Certain details recall in a

vague way Second Empire prototypes. In addition to the mansard roof,

there is the attempt to articulate the wall surface through the use of

bay windows and recessed panels. The plain effect of the façade was

originally relieved by a verandah that ran across the front and down one

side of the residence. Local tradition claiming that this house was

erected for barrister and M.P.P. Clifford Sifton remains to be proven.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

115

Creighton Terrace

33 Fourth Street, Emerson, Manitoba

Constructed: 1885-86

Material: Brick

Creighton Terrace was put up at the peak of Emerson's boom-town growth,

before an alternate railway route dimmed the town's hopes of becoming

the permanent gateway to western Canada. Erected by developers Noble and

Fallis, the terrace was probably named in honour of W.D. Creighton,

part-owner of the property in the early 1880s. Conveniently located

near the Red River and original town core, and fitted up with a

fashionable mansard roof, this triple dwelling offered superior

accommodation for newcomers to Emerson. The first tenants to occupy

Creighton Terrace were barrister Archibald Mackay, law clerk David

Mackay and deputy postmaster and operator of the Canadian Pacific

Railway Telegraph Company, T.W. Mutchmor. According to local

information, the builder was a man called Bryce.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

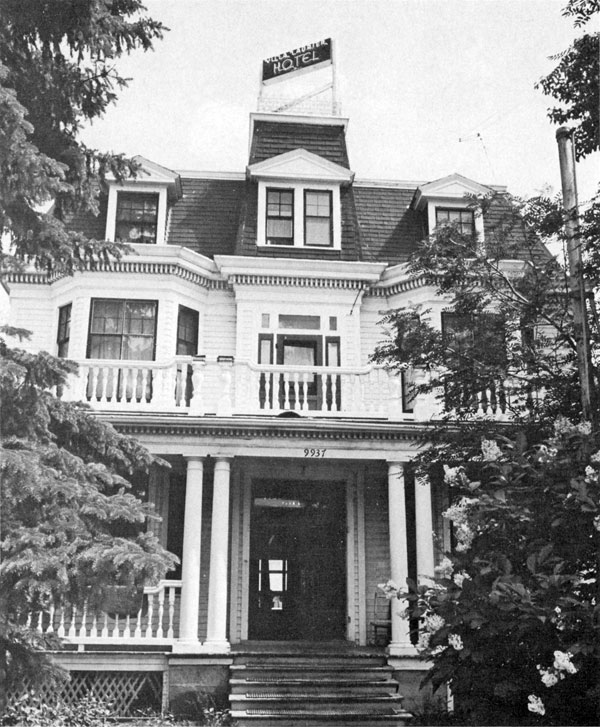

116

Villa Laurier Hotel

9937 108th Street, Edmonton, Alberta

Demolished: ca. 1972

Material: Wood

The Villa Laurier Hotel would appear to have been built as a single

family dwelling; however, since 1914 it has been used as a boarding

house. This is one of the few examples of residential building in the

Prairies, with the exception of Winnipeg, where the influence of Second

Empire goes beyond the borrowing of the mansard roof. The two-storey bay

windows, central tower and iron cresting indicate a more serious attempt

to imitate the purer examples of this style. Perhaps its name, Villa

Laurier, was chosen to reflect the "frenchness" of its design.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

117

610 Buxton Street, Indian Head, Saskatchewan

Constructed: 1890-91

Material: Stone

Erected in 1890-91 for a local farmer, Joseph Glenn, this is the

only surviving stone house in Indian Head, an early western community on

the main Canadian Pacific Railway line. In addition to its stone

construction, the dwelling is remarkable for its flat mansard roof

trimmed with gay iron cresting, so popular in the Second Empire idiom.

Although no architect was apparently involved in the project, the

builders have been identified as stone mason John Hunter and carpenter

A.M. Fraser. The house remains the property of the Glenn family to this

day.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

118

1124 Fort Street, Victoria, British Columbia

Constructed: ca. 1887

Material: Wood

This substantial dwelling is one of Victoria's oldest surviving

buildings. Following the trend set by contemporary buildings in the city

such as the Post Office, Custom House and Public School, this house pays

tribute to Second Empire fashion in such details as the mansard roof,

projecting central pavilion crowned by a mansard tower and the

repetition of semicircular motifs in the attic windows. The roof has

regrettably lost its fish-scale shingles arranged in bands of different

colours. The original owner, Thomas Joseph Jones, a native of Toronto,

was one of Victoria's most successful dentists.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

119

507 Head Street, Esquimalt, British Columbia

Constructed: 1893

Material: Wood

One of the most picturesque Second Empire houses on Vancouver Island,

507 Head Street bears witness to the late flowering of this fashion in

the west. The house has an elaborate mansard roof with convex ribs and

shaped shingles as well as two asymmetrical towers, one on the main

façade, another along a lateral wall. A curious feature is the iron

cresting placed above the cornice and not on top of the roof. The house

was built for Captain Victor Jacobson, a sealer who anchored his

schooners just off the beach in front of the property. He apparently did

all the fancy carving for the roof trim himself. According to his

daughter, the oak panels in the dining room, depicting flowers, animals

and fish, were carved "by my father ... while waiting for seal herds to

enter the Bering Sea or while his schooner was be calmed, from the

patterns my mother drew."

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

|