|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 24

Second Empire Style in Canadian Architecture

by Christina Cameron and Janet Wright

Illustrations and Legends

31

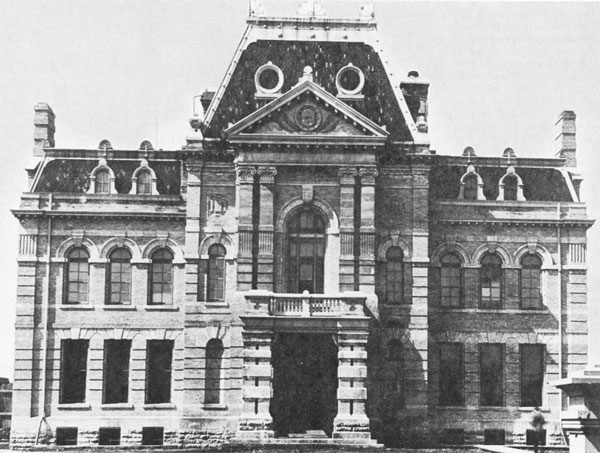

Law Courts Building

171 Richmond Street, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

Constructed: 1874-76

Architect: Thomas Alley

Material: Brick

The Law Courts Building offers a simplified version of the Second Empire

style in public building. Pavilions have been suggested in the four

central towers but these forms are not continued below the eaves line.

The cut stone trim and highly decorative brick work under the eaves

(features typical of Alley's work) add colour and texture to these

surfaces but lack the full sculptural feel of high Second Empire

detailing.

Despite its modest execution, this building achieved a sense of grandeur

in the context of its site. Prominently situated on Queen's Square in

the heart of Charlottetown, it stood next to the Provincial Building and

was counter-balanced on the west side of the square by the Post Office.

Together these three buildings created an imposing architectural

ensemble that visually proclaimed their role as the core of provincial

authority. Unfortunately the Pest Office is no longer standing and the

Law Courts Building was severely damaged by a fire in 1976.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

32

Court House

Kennedy Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1882-83 Destroyed by fire: 1957

Architect: C. Osborn Wickenden

Material: Brick with stone trim

With the erection of the Winnipeg Court House, Second Empire burst upon

this prairie town with a sophistication that could rival almost any

building in eastern Canada. Though not large, it has strength and

monumentality as a result of its harmonious proportions and careful

detail. All the standard Second Empire features are used, including

symmetrical massing, mansarded tower, superimposed orders, semicircular

and round windows, and of course the rich sculptural texture of the

façade. "Designed after the French Renaissance," according to one

contemporary source, the Court House became a landmark because of its

80-foot tower, "the highest in the city and a conspicuous object for

miles around."

To produce such a fashionable building, it is hardly surprising that

provincial authorities called upon an architect and contractor of

experience. Wickenden, trained as an architect in England, had worked in

New York before emigrating to Saint John, N.B. after the 1877 fire. It

was in Saint John that he met J.G. McDonald, contractor for several

major buildings at the time. They may well have decided together to try

their fortune in boom-town Winnipeg where they collaborated on the Court

House.

Ranged along Kennedy Street beside two other Second Empire buildings,

the Parliament Buildings (Fig. 28) and the Lieutenant-Governor's

residence, the Winnipeg Court House contributed to an imposing

streetscape that served as a fitting embodiment of the power and

permanence of government.

(Provincial Archives of Manitoba.)

|

33

Victoria City Hall

Centennial Square, Victoria, British Columbia

Constructed: 1878, 1881, 1890

Architect: John Teague

Material: Brick

John Teague, a native-born Englishman, settled in Victoria in 1858 and

worked for a number of years as a contractor for the naval dockyards. In

1875 he set himself up as an architect and became the major local

designer of the period. His most important work was the City Hall and,

like many of his other public buildings, it was designed in his own

particular version of the Second Empire style. It is interesting to

compare Teague's building of 1878 with Perrault's Montreal City Hall

(Fig. 1), just being completed that year, to demonstrate the widely

differing interpretations possible within this idiom. In contrast to

the heavy, plastic massing and detail of Perrault's design, the Victoria

City Hall is more compact in plan and elevation, and has shallow

detailing of a lighter and more two-dimensional character. In Victoria

the style was labelled as either the "Italian" or "Anglo-Italian" style

and in fact an Italian renaissance influence is evident in the

round-headed windows with their circular tracery motif.

Although entirely designed by John Teague, the City Hall did not assume

its final appearance until 1890. Because of financial difficulties only

the south wing, defined by the three bays to the left, was erected in

1878. In 1881 the Fire Hall was added to the rear of the south wing and

by 1890, the economy of Victoria having greatly improved, the main

façade was extended by 82 feet along Douglas Street and the clock tower

was added.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

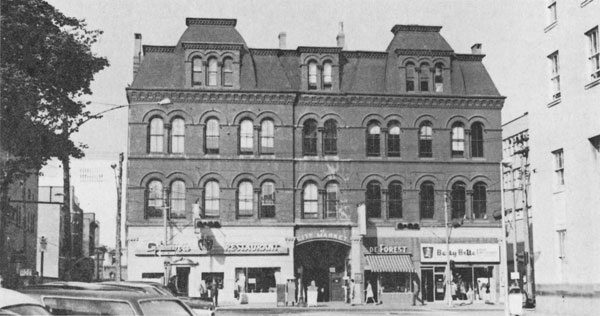

34

City Market Building

47 Charlotte Street, Saint John, New Brunswick

Constructed: 1876

Architects: J.T.C. McKean and G.E. Fairweather

Material: Brick

This market building was preceded by two earlier structures, both of

which were constructed of wood and later destroyed by fire. To prevent a

third mishap the new market was constructed of brick, a worthwhile

expenditure for it was one of the few buildings in the area to survive

the fire of 1877. Similar in spatial organization to a railway station,

the plan consists of a front block with an imposing entrance, office

space and an actual market area housed in a long functional structure at

the rear, well lit by a row of clerestorey windows. The façade

articulation with its semicircular windows and corbelling under the

eaves seems to be a favorite decorative combination for public buildings

of the Second Empire style in the Maritimes. Comparable treatment of

exterior design can be found on the Charlottetown Law Courts (Fig. 31)

and the Public School at Truro (Fig. 41).

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

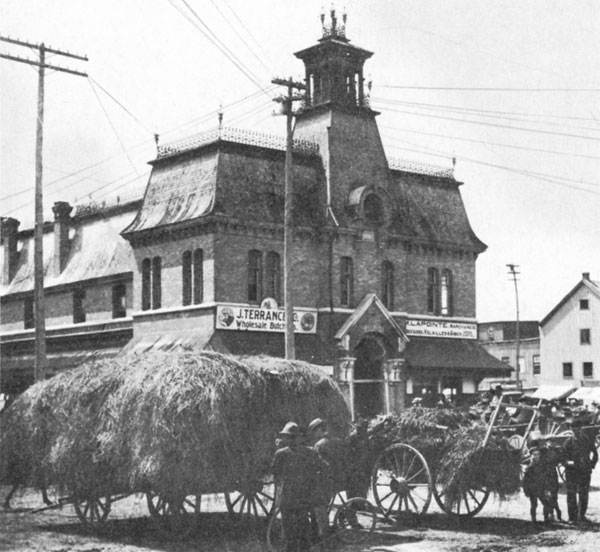

35

Byward Market Building

York Street, Ottawa, Ontario

Constructed: 1865-76

Architect: Robert Surtees?

Material: Brick

Following the lead of the federal government most Ottawa municipal

buildings in the 1870s, including the City Hall of 1878 (demolished in

1931), were designed in the Second Empire style. Ottawa's Byward Market

building, like the City Market building in Saint John, New Brunswick, of

the same year, was planned with a long utilitarian market hall hidden

behind a more style-conscious entrance block. It is a modestly detailed

building but attractive for its gracefully flared mansard roof and

central pavilion topped by a delicate, jewel-like lantern. Although the

documentation is not conclusive, the design was probably the work of

city engineer, Robert Surtees.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

36

Falconwood Lunatic Asylum

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

Constructed: 1877-78 Demolished

Architect: David Stirling

Material: Brick

In 1876 a competition was held for the design of the new Falconwood

Lunatic Asylum. Eleven proposals were received and the contract was

awarded to David Stirling of the Halifax firm of Stirling and Dewar.

This firm had just completed a mansarded design for the Halifax Poor

House in 1875 and it was perhaps this experience in institutional

building that gave them an advantage over the other competitors.

The design reduced the Second Empire style to its most simple geometric

forms. All decorative details were stripped away, leaving a pavilioned

plan of heavy broad masses which pivot around the central block and

tower. This illustrates well the close interrelationship between form

and planning in that each of the separate units was an outgrowth of

interior function. The central block housed administrative services; day

rooms and recreation halls were located in the pavilions, and the

intervening spaces were occupied by dormitories. The above illustration

does not represent the building as completed, since research indicates

that only the west or left-hand wing and central block were erected in

1877. The east wing was built between 1896 and 1901 in a similar style

but with modifications to the original plans.

(L'Opinion publique [Montreal], 23 mars 1878, p. 180.)

|

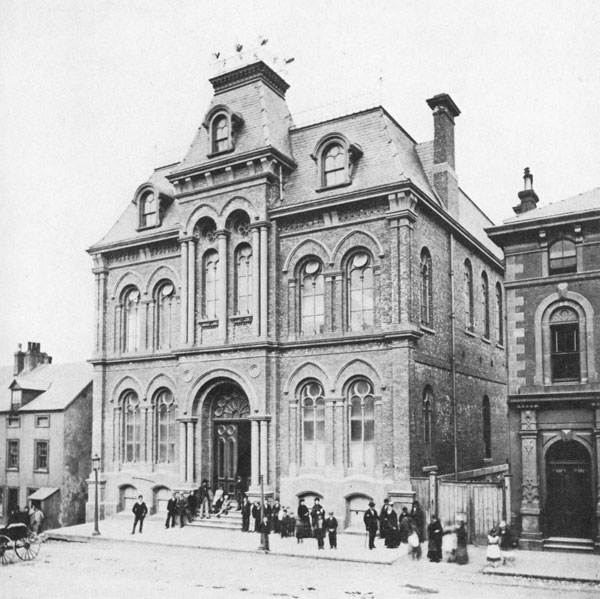

37

The Athenaeum

Duckworth Street, St. John's, Newfoundland

Constructed: 1875-78 Destroyed: 1892

Architects: J. and J.T. Southcott

Material: Brick

In March 1861, the St. John's Library and Reading Room, Young Men's

Institute, Mechanic's Institute and Museum were amalgamated into the

Athenaeum. Land was granted by the governor for a building on Duckworth

Street; however, construction did not begin until 1875. The design was

by the father and son firm of J. and J.T. Southcott, leading local

architects working primarily in the Second Empire style who provided a

key impetus in creating the immense popularity of this style in St.

John's. The lively exterior composition, which has been unified by the

play of semi-circular and circular motifs of the door and window tracery

and surrounds, reveals the accomplished style of the Southcott family.

This building was one of many lost in the fire of 1892.

(Newfoundland Public Library Board.)

|

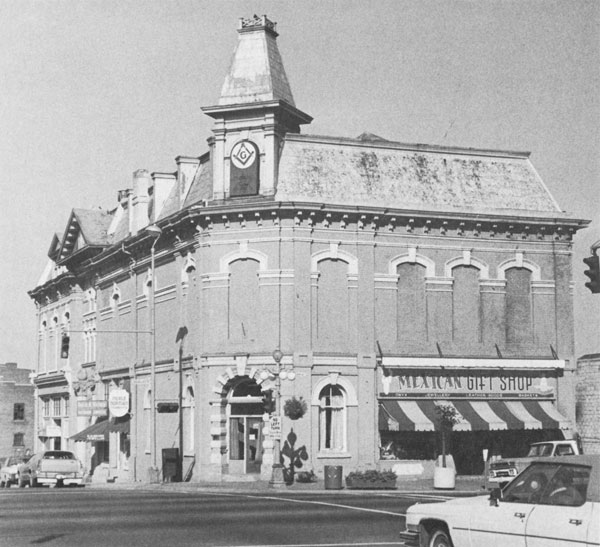

38

Masonic Temple

650 Fisgard Street, Victoria, British Columbia

Constructed: 1878

Architect: John Teague

Material: Brick

Like the Y.M.C.A., the Order of Freemasons favoured the Second Empire

style for their lodges during the 1870s. An example of this period of

building is the Masonic Temple in Victoria, designed by the city's

leading architect, John Teague, who was working primarily in the Second

Empire style (see Fig. 33) and who, not surprisingly, was also a

prominent member of the Masons. The construction contract was awarded

to the firm of Dinsdale and Malcolm of Victoria. As originally

constructed the building extended four bays along Douglas Street and

three bays along Fisgard Street with a corner entrance accented in the

roofline by a small tower. Shops occupied the ground floor and the lodge

facilities were located on the second floor. In 1909 a large addition

was built on the Fisgard Street façade and the original second-storey

windows were bricked in giving the design, which was plain at the

outset, its flat, lifeless appearance.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

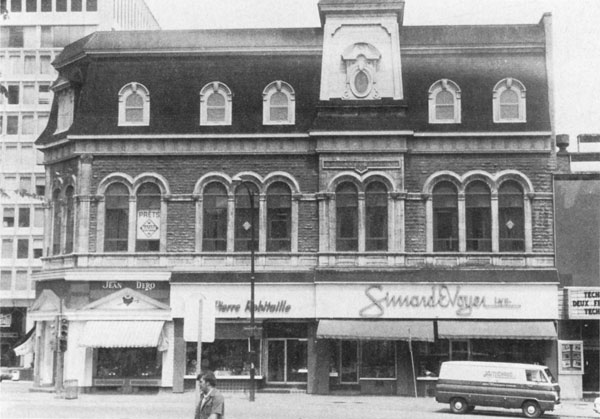

39, 40

Young Men's Christian Association

950-964 Saint-Jean Street, Quebec, Quebec

Constructed: 1879

Architect: Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy

Material: Stone

The extant Y.M.C.A. building in Quebec has an asymmetrical plan,

probably due to the exigencies of the building lot, but in other

respects illustrates the major stylistic features of Second Empire. The

contrasting colour and texture of the masonry, the fine detailing

coordinated by rhythmic successions of structural openings, and the

picturesque silhouette reflect the delight in rich surfaces and outline

so characteristic of this style. The building initially housed four

shops, a lecture hall, reading room, gymnasium and numerous apartments;

however, all that remains of the once elegant interior is a grand

staircase. Over the years, the exterior of the building has been sadly

altered. The arcaded storefronts have been replaced by plate-glass

windows and the roof has lost its patterned shingles, iron cresting and

ornamental chimneys. In its present state, the Y.M.C.A. building in

Quebec has a stolid and top heavy appearance far from its original

inspiration.

(Fig. 39, source unknown; Fig. 40, Canadian Inventory

of Historic Building.)

|

41

Provincial Normal School

748 Prince Street, Truro, Nova Scotia

Constructed: 1877-79

Architect: Henry F. Busch

Material: Brick

Like many educational institutions in Canada during the 1870s, the

Provincial Normal School, erected by the Provincial Department of

Education as a teachers' training centre, was designed in the Second

Empire style. Features such as the balanced pavilion massing and the

play of concave and convex forms in the mansard roof were drawn from the

Second Empire vocabulary; however, unlike the heavy classical detail

found in purer forms of this style, the façade is lightly articulated by

contrasting patterns and colours of brickwork. This lively appearance is

further enhanced by the repetition of semicircular and circular forms

which unite the façade. As originally built the roofline was decorated

with iron cresting and a small ornamental cupola over the central

pavilion. The architect, Henry F. Busch of Halifax, seemed to be a

favourite of the Department of Education for in 1878 he produced a very

similar design for the Halifax County Academy on Brunswick Street in

Halifax.

(Engineering and Architecture, Department of Indian

Affairs and Northern Development.)

|

42

Pavilion central, Laval University

3-7 University Street, Quebec, Quebec

Constructed: 1854-56; addition 1875-76

Architects: Charles Baillairgé and Joseph Ferdinand Peachy

Material: Stone

Seen from the rear in this view, the main college building of Laval

University is faithful to Baillairgé's design with the exception of the

roof. Baillairgé's original conception for the structure called for a

flat roof deck surrounded by an elaborate cast-iron balustrade. By the

1870s, this severely rectilinear design was apparently considered

inappropriate, and the Seminary of Quebec engaged Peachy, a former

apprentice of Baillairgé, to add the robust mansard roof. The

round-headed dormers, iron cresting, central pavilion with lantern and

side lanterns with weathercocks all contribute to the picturesque effect

so dear to Second Empire ideals. The actual construction was carried out

by master joiner Ferdinand de Varennes, a frequent collaborator with

Peachy. Perched on the rock of Quebec overlooking the Saint Lawrence

River, this gleaming metal-covered roof continues to be a prominent

landmark of Old Quebec.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

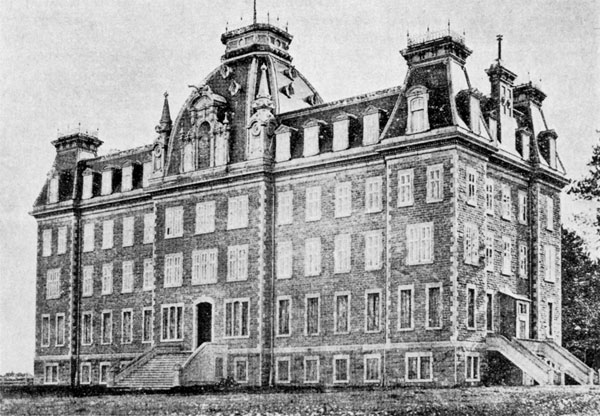

43

Collège du Sacré-Coeur

College Street, Sorel, Quebec

Constructed: 1877 Demolished

Architect: L.-Z. Gauthier

Material: Stone

The new college is an odd combination of traditional Quebec traits and

fashionable Second Empire. The walls of evenly coursed rough-faced stone

and the smooth cut-stone trim around doors and windows are common Quebec

features. But the use of central and side pavilions, marked by cut-stone

quoins, and the wonderfully flamboyant roof with convex central cupola

and concave corner towers illustrate the inroads made by the new

fashion. The architect of the Collège du Sacré-Coeur, L.-Z. Gauthier,

later worked in Ottawa on a design for the western wing of the

Archbishop's Palace. The construction of the college was supervised by

Father Arthur St-Louis. The building's function as a classical college

was short-lived, for the authorities were unable to obtain adequate

funding and declared bankruptcy in 1880. From 1883 to 1888 it served as

an Anglican high school under the name Lincoln College. The building

remained empty until 1896 when it was refurbished by the Révérends

Frères de la Charité of Montreal for use as a catholic commercial school

known as Collège Mont-Saint-Bernard.

(Dominion Illustrated [Montreal], 18 April 1891, p. 375.)

|

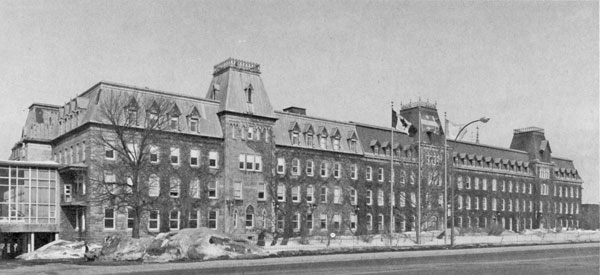

44

Collège Notre-Dame

3791 Queen Mary Road, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1880-81

Architects: François and D.A. Lapointe

Material: Stone

Although the architects for the college are identified as François and

D.A. Lapointe, they apparently adopted with minor modifications an

earlier design presented by prominent Montreal architect H.M. Perrault

which was rejected by college officials. The building was intended to

provide space for classrooms and student dormitories. True to the

eclectic spirit of the age, the design combines Second Empire features

with others borrowed from the Gothic Revival style, popular at that time

in religious architecture. The original structure, now the central

section of the enlarged building, was a plain mansard-roofed block with

a central mansarded pavilion. The ecclesiastical affiliations of the

college were expressed through the use of pointed gothic openings for

the windows and door of the central pavilion and through the slender

steeple (never built) that was meant to surmount the earth-bound tower.

The added wings on each side of the building are sympathetic to the

original design.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

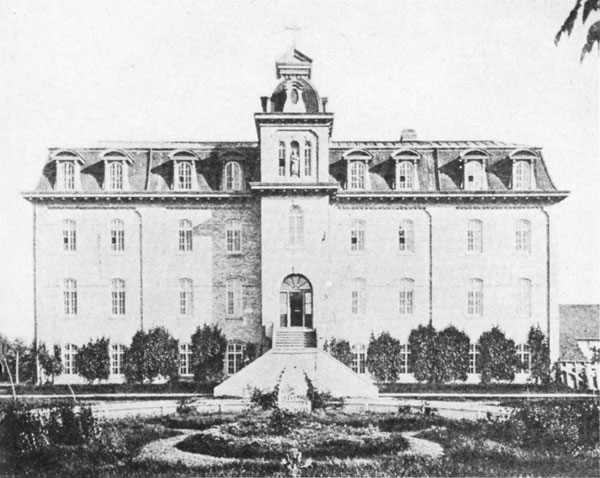

45

Saint Boniface College

Provencher Avenue, Saint Boniface, Manitoba

Constructed: 1879-81 Destroyed by fire: 1922

Architect: Balston C. Kenway

Material: Brick

The moving force behind the construction of Saint Boniface College was

Monseigneur Alexandre Taché, Archbishop of Saint Boniface, whose

determination to educate the French-speaking population of Manitoba is

well known. This particular building, situated in a wooded area east of

the old college and cathedral, housed the principal Catholic school in

Manitoba at that time. Monseigneur Taché perhaps chose Kenway as his

architect because of his familiarity with ecclesiastical construction:

prior to his arrival in Winnipeg, Kenway had been architect and overseer

for extensive renovations to the Old Stone Church in Saint John, New

Brunswick. The contractors for Saint Boniface College were Gill and

Mould, and J.B. Morache. Clearly functional in design and detail, the

college falls naturally into the tradition of mansard-roofed buildings

so familiar in ecclesiastical circles in Quebec. Only the central

pavilion with its convex-ribbed tower makes an explicit reference to

Second Empire sources. Early in the 20th century, wings were added to

each side of the original structure.

(Provincial Archives of Manitoba.)

|

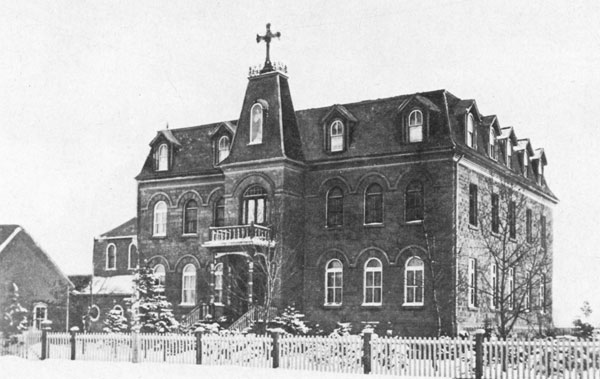

46

Sacred Heart Convent, F.C.J.

219 19th Avenue SW., Calgary, Alberta

Constructed: 1893-94 Additions: 1924

Material: Stone

In 1885 the Sisters, Faithful Companions of Jesus established the first

private school in Calgary, offering a full education in both English and

French to girls from Roman Catholic families. Several years later, under

the direction of the Superior of the Convent, Reverend Mother Mary

Greene, this building was erected to provide more space for classrooms

and living quarters for the Sisters and boarders. The builder and

contractor was Thomas Underwood. Although the design for the Convent

lacks the plasticity found in fancy Second Empire buildings, it

nevertheless has such features as the mansard roof, central pavilion and

a pleasing rhythm of semicircular openings. As it appears in this early

photograph, the Sacred Heart Convent corresponds to a description found

in the Annals of the Sisters, who were evidently well pleased with the

structure. "The exterior of the house is nicely finished off. The

pillared portico surrounds the front door, on the top of which is a

balcony, to which we have access by a double glass door, opening from

the hall of the second storey. Above this balcony in a niche covered

with glass stands an exquisite statue of the Sacred Heart, 5-1/2 feet

high, the gift of the Rev. Father Lacombe, O.M.I., who pronounces the

building a perfect success and a credit both to the workmen and to those

who planned the edifice."

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

47

Molson Bank

288 Saint James Street West, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1866

Architect: George Browne

Material: Stone

Built in 1866 the Molson Bank represents an early and formative stage of

Second Empire in Canada. The self-contained block plan is simpler than

the complex pavilion massing of high-style Second Empire and the roof,

while gaining in prominence, has not yet taken on its full bombastic

dimensions nor acquired the lively silhouette so characteristic of this

style by the early 1870s. Nevertheless, the feeling of richness and

plasticity created by the broken wall planes and projecting cornices,

the baroque quality of the rich garlanded consoles of the attic storey

(a motif prominently featured on the New Louvre), and the use of iron

cresting and tall chimneys all anticipate the arrival of Second

Empire.

George Browne, born in Belfast in 1811, was one of Canada's most

prominent and brilliant architects of the 19th century. The Molson Bank

was a late work, yet even at this advanced stage in his career he was

able to incorporate new stylistic trends. It is not surprising, however,

that Browne should have responded so enthusiastically to this new

fashion for, as has been pointed out in J. Douglas Stewart's essay on

Browne's Kingston architecture, his style always had an element of the

"neo-baroque" in its material, texture, mass, and effects of light and

shade. These characteristics can be found in the Molson Bank where,

under the influence of the Second Empire style, they become enriched

and accentuated.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

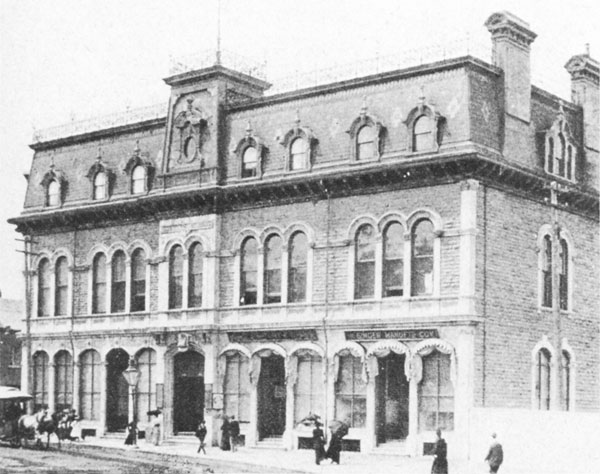

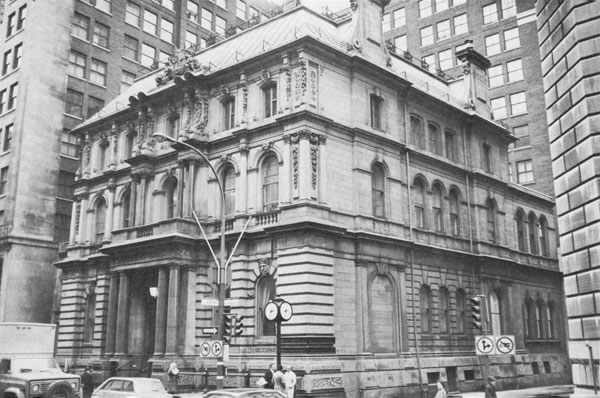

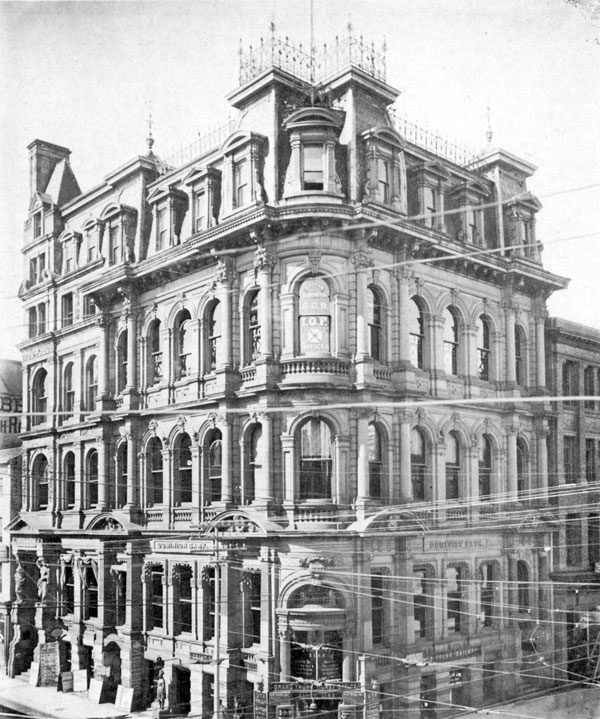

48

Dominion Bank

King Street West at Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1877-79 Demolished: Before 1914

Material: Stone

From the year of its founding in 1871 until 1879 the Dominion Bank was

housed in a leased storefront office on King Street East. The

construction of a permanent banking house in 1877-79 was seen as a

symbol of the Bank's maturity; the lavishness of the design, heavily

ornamented with rich classical detail, would have offered further

assurance to the public of the wealth and financial stability of this

institution. The use of a corner entrance was a common compositional

device for buildings located at an intersection; the rounded corner

created a smooth visual transition between two façades at right angles

to each other. Although enlarged in 1884, probably by the three-bay

section visible to the left of the photograph, the Dominion Bank had

outgrown this building by the early 20th century and in 1914 was

replaced by a new head office designed by the Toronto architectural

firm of Darling and Pearson.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

49

View of Wellington Street in 1896

Ottawa, Ontario

This photograph of 1896, depicting from left to right, La Banque

Nationale, the Bank of Ottawa and a corner of the Quebec Bank,

illustrates the unified architectural character of Wellington Street in

the post confederation era. Many features, such as the rusticated

ground floor, round-headed windows and banded columns were borrowed

from the new Post Office of 1873 (Fig. 19) which marked the eastern end

of the street and these motifs were repeated further west in the design

for the Bank of Montreal. This uniformity was certainly no accident for,

following the example set by Baron Haussmann's urban planning in Paris,

all building along Wellington Street had to be approved by the federal

government. The result was the creation of a grand Second Empire

thoroughfare which provided Canadians with an imposing symbol of the

power and stability of their new nation.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

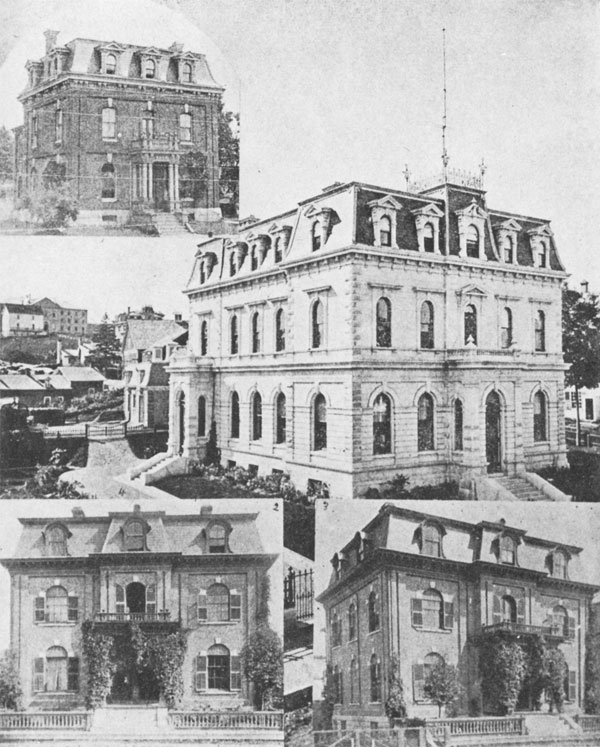

50

Eastern Townships Bank

Head Office

241 Dufferin Street, Sherbrooke, Quebec

Constructed: 1875-76

Architect: James Nelson

Material: Stone

Branch Offices:

(1) 191 Principale Street, Richmond, Quebec

Constructed: 1876 Material: Brick

(2) 225 Principale Street, Cowansville, Quebec

Constructed: 1874-75 Material: Brick

(3)19 Gerin Lajoie Street, Coaticook, Quebec

Constructed: 1873-74 Material: Brick

By the mid-1870s the Eastern Townships Bank founded in 1859 had,

according to its annual report of 1873, increased its business to such

an extent that many of its old buildings were no longer adequate in

size. Between 1873 and 1876 a head office in Sherbrooke and three branch

offices in Richmond, Cowansville and Coaticook were constructed, all of

which were designed in the Second Empire style. For the branch offices

the Directors were "fully aware of the objections in the minds of some

of the shareholders to an expenditure on what is called 'bricks and

mortar'," and for this reason a very simple, standardized plan, which

looks more like a residential building, was adopted, keeping the

average cost of construction to $6,000. All three of these buildings

have survived but none still functions as a bank.

(Dominion Illustrated [Montreal], 30 August 1890, p. 133.)

|

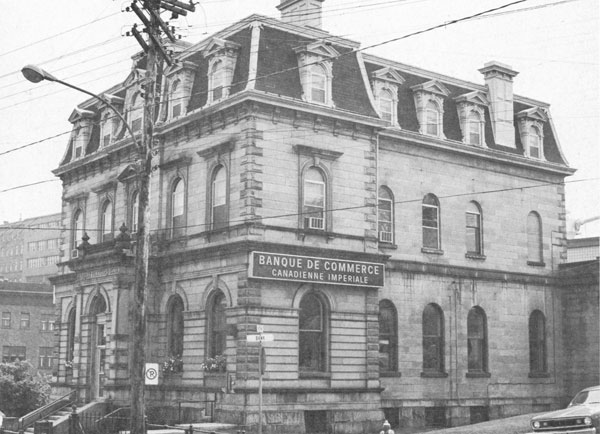

51

Eastern Townships Bank

241 Dufferin Street, Sherbrooke, Quebec

Constructed: 1875-76

Architect: James Nelson

Material: Stone

A design for the new Head Office in Sherbrooke was not approached with

the economical restraint shown for the branch banks. The Annual Report

of 1874 states that "the Directors feel also that in a work of this

kind ... they are justified in having a handsome as well as useful

building, and they believe that the shareholders will agree with them in

the opinion that while extravagance should be avoided, yet there is

something due to the position of the Bank as one of the most successful

institutions in the country."

James Nelson, prominent Montreal architect, was commissioned to prepare

the plans and the $37,000 construction contract was awarded to Mr.

Quigley and Company, "late of Quebec." A new rear wing was added in

1903. This building still functions as a bank, serving as the branch

office of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce since its amalgamation

in 1911.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

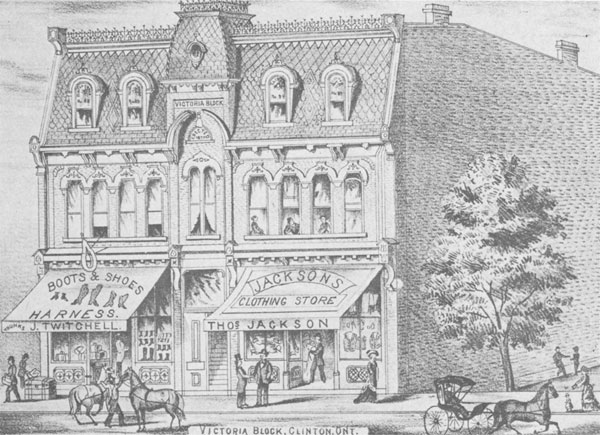

52

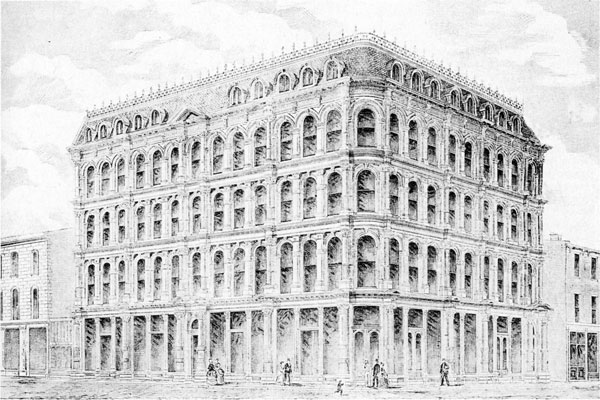

The Victoria Block in 1879

|

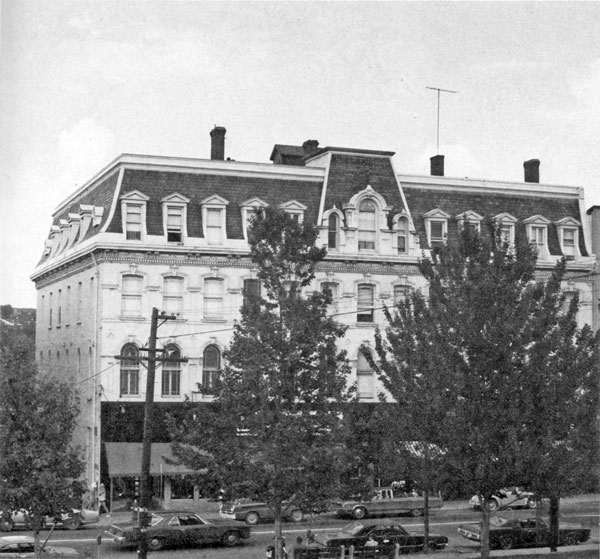

53

Victoria Block

15-17 Victoria Street, Clinton, Ontario

Constructed: 1877-78

Builders: William Cooper and Thomas Mackenzie

Material: Brick

Typical of commercial building, the Victoria Block has compressed the

sculptural massing of the high Second Empire style into a compact,

rectangular plan. The projecting tower and the central focus of the

façade create the illusion of the characteristic pavilion plan without

its space-wasting projections on the street front. But for the loss of

the roof cresting and alterations to the storefront windows the building

has changed little over its 100-year history and even today it remains

a prominent feature of the town's streetscape.

William Cooper and Thomas Mackenzie owned a planing mill and ran a

successful contracting business in Clinton. It has not been determined

whether they were responsible for the design of the Victoria Block or

whether they were working under the direction of a yet unknown

architect.

(Drawing, H. Belden and Company, Illustrated Historical Atlas of

Huron County, Ontario [1879; reprint ed., Belleville, Ontario:

Mika Silk Screening, 1972], p. 18; photograph, Canadian Inventory of

Historic Building.)

|

54

Saint James Street, Montreal, Quebec

Looking south along Saint James Street, the four-storey building on the

right in the foreground was erected in 1871 for the City and District

Savings Bank. Across St. John Street on the other corner is the enormous

structure built by Thomas Barron and known as Barron Block (Fig.

55).

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

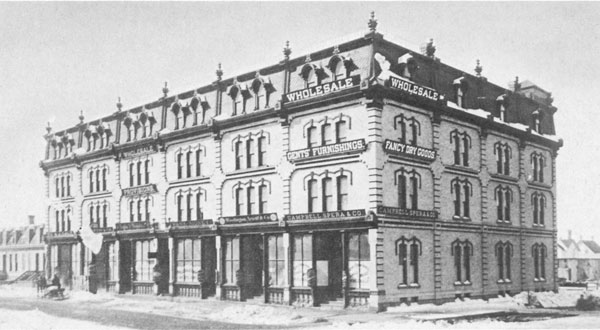

55

Barron Block

Saint James Street, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1870-72

Architect: Michel Laurent

Material: Stone

This massive commercial block, situated at the corner of Saint James and

Saint John streets in what was referred to as "one of the most princely

parts of the city," provided prestigious office space for the Montreal

business community. While economic considerations may have determined

the use of a block plan which made maximum use of the expensive urban

lot, its embellishment was certainly not fettered by any sense of

frugality. The four-storey design has been punctuated by large, arched

windows surrounded by pilasters and finely carved stone decorations.

Each floor is divided by a heavy entablature which breaks forward at

intervals to be supported by columns of the ornate Corinthian order.

Despite the simplicity of the plan this lavish plastic ornamentation

gave the building a palatial appearance appropriate for offices of many

of the city's merchant princes.

(Canadian Illustrated News [Montreal], 27 Aug. 1870, p. 136.)

|

56

Odell Block

172-184 Wellington Street North, Sherbrooke, Quebec

Constructed: between 1877 and 1881

Material: Brick

Construction of the Odell Block, now known as the Gregoire Building, was

probably begun soon after 1877 when the owner, Thomas B. Odell,

purchased from a Mr. Long a small parcel of land adjoining his own

property on Wellington Street which together made up the site of his

new building. The construction contract was awarded to G.B. Precourt but

the design was very likely the work of an outside, yet unnamed

architect. Following the standard arrangement for a business block the

ground floor was "divided into a number of large and spacious

stores..., The upper flats of the building being occupied by lawyers,

notaries and insurance agents." The Odell Block, typical of large

commercial buildings of the Second Empire style, was distinguished,

however, in its original form by the extensive use of oval dormers that

lined the mansard roof — since replaced by the present round- and

flat-headed dormers.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

57

233-237 Dundas Street, London, Ontario

Constructed: 1875

Material: Brick

Commercial blocks such as this could have been found in most urban

centres across Canada of the 1870s and 1880s. Unlike the often grand

and lavishly executed Second Empire designs constructed for public and

even commercial institutions such as banks, these commercial blocks,

generally built as investment properties to be leased out, did not

function as architectural symbols representing a specific organization.

The designs tended to reflect greater economy, in order to provide a

maximum return for the investor. The typical solution, as illustrated

by the Dundas Street block, was a building compact in plan, making full

use of the expensive urban lot but sufficiently rich and grand in detail

to attract an affluent clientele.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

58

Osler Block

5-7 Main Street, Dundas, Ontario

Constructed: Before 1875

Material: Brick

As it appears today Osler Block has been stripped of all its festive

Second Empire dress resulting in its present austere appearance. In its

original condition, iron cresting trimmed the roof, carved woodwork

decorated the dormer windows and an additional tripartite dormer with

semicircular openings accented the small projecting pavilion. Only the

coloured and patterned shingles of the mansard roof preserve a hint of

its once picturesque demeanor. The second storey remains unchanged but

the ground floor has been completely altered by the loss of a

plate-glass store-front which occupied the four right-hand bays and by

the removal of the decorative pediments which defined the windows and

two main doorways, one centrally placed on the façade and the other on

the far left-hand side of the building.

Osler Block was built as an investment property for Briton Bath Osler, a

prominent Hamilton lawyer and entrepreneur who resided in Dundas. The

ground floor was leased as office space while the second floor was, and

still is, occupied by the local Masonic Lodge.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

59

Gerrie Block

Princess Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1881 Demolished: ca. 1956

Architect: Charles A. Barber

Material: Brick

Gerrie Block is one of a series of warehouses built in this district

during the years of Winnipeg's rapid expansion. The six attached brick

structures known as Gerrie Block were erected by R. Gerrie and Company

for wholesale mercantile purposes. In spite of the utilitarian function

of the warehouses, the design is an attractive version of Second Empire,

especially in the handling of the mansard roof with its cresting,

patterned shingles and semicircular dormers. The potential monotony of

the broad roof is relieved through the rhythmic articulation of

individual units, punctuated by ribs and carved finials. Although

economic considerations are evident in the careful use of the city lot

and the modest ornamentation, Gerrie Block is, in the context of

warehouse construction, a fashionable and well-appointed building.

(Provincial Archives of Manitoba.)

|

60

Windsor Hotel

Peel Street, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1876-78 Demolished: ca. 1960

Architect: William W. Boyington

Material: Stone

One of the finest examples of Second Empire design in Canada was

Montreal's Windsor Hotel. At the time of its erection, it ranked among

the most luxurious hostelries in North America. Contemporary observers

praised its elegant fittings including "the main dining-hall with its

marble floors, gigantic mirrors, and lovely landscape paintings," the

grand promenade which "fairly bewilders the eye with its splendour,"

the bridal chamber, a "charming bijou" with velvet carpet and

furniture in silk, and the entrance hall which "reminds the traveller

of some of those grand old Italian palaces." To complete this vast

project at the cost of almost one million dollars, the sponsors engaged

an American architect experienced in hotel construction, William W.

Boyington of Chicago, and drew on numerous local and American firms and

craftsmen. The first lessee was J.W. Worthington of Montreal. The

impact made by the Windsor Hotel is well summed up by a contemporary

traveller from Britain who writes that "the rooms of the Windsor at

Montreal fairly astonished us. There is nothing in the hotel way in

London comparable to the house, except perhaps the Grand at Charring

Cross and if adjectives must be used I could say the Windsor was the

grander of the two."

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

|

|

|

|