|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 24

Second Empire Style in Canadian Architecture

by Christina Cameron and Janet Wright

Illustrations and Legends

1

City Hall

275 Notre Dame Street East, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1872-78 (severely damaged by fire 1922, rebuilt)

Architect: H.M. Perrault

Material: Stone

With its mansard roof, pavilion massing, classicizing decoration and

fine setting, Montreal City Hall, described in detail in the text,

stands as a handsome early example of Second Empire design in

Canada.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

2

New Louvre

Paris, France

Constructed: 1852-57

Architects: L.T.J. Visconti and Hector-Martin Lefuel

Material: Stone

The Louvre was begun in the 16th century by Pierre Lescot and continued

by a succession of architects over the next 300 years. Napoleon III's

decision to link up the Louvre with the Palace of the Tuileries required

a design that would be compatible with the existing buildings. As a

result the design of the new wing, which was conceived by Visconti and

continued after his death in 1853 by Lefuel, borrowed many features from

the older parts of the building such as the high-pitched mansard roof,

horizontal emphasis and sculptural ornamentation; however, these forms

were so vigorously interpreted that they created a robust and original

architectural character.

Had this building been erected anywhere else but Paris, the design would

probably not have had the same dramatic impact. The elegance of the

court of Napoléon III and the ambitious urban planning schemes of Baron

Haussmann had captured the imagination of the western world and earned

the city its reputation as the model of cosmopolitan modernity. For the

outside world the New Louvre became a symbol of this new progressive

age.

(Library of Congress.)

|

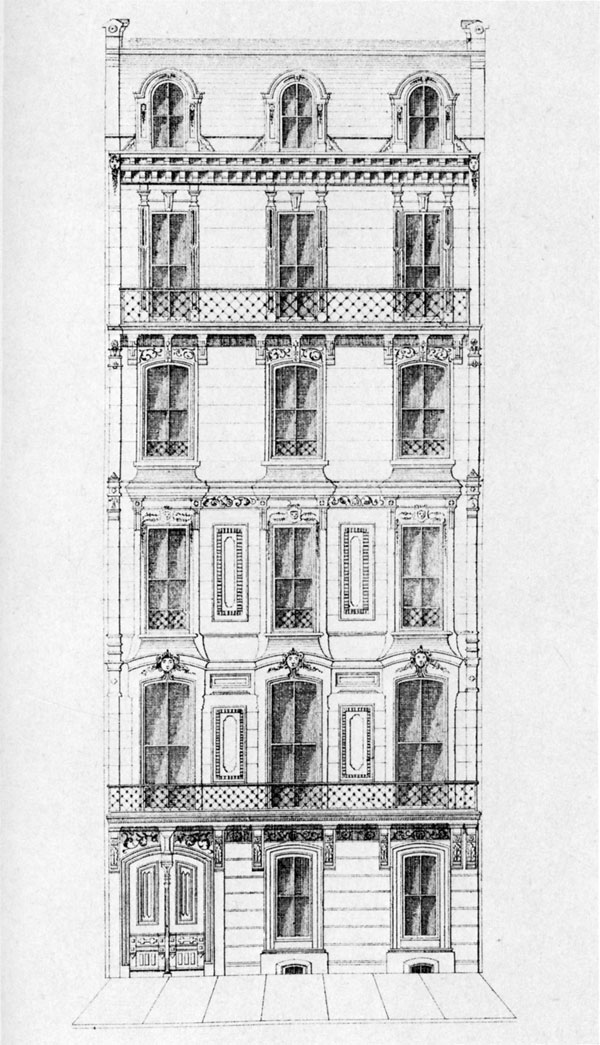

3

Re-creation of a typical Paris apartment

Architects: Sanford E. Loring and William Le Baron Jenning

Published: 1869

This re-creation of a typical Paris apartment of the Second Empire

period illustrates the type of buildings which lined the broad

boulevards created by Baron Haussmann. They were usually six or seven

storeys high with a shop and living quarters for the concierge on the

ground floor and a porte cochère wide enough to admit a carriage into the

narrow court leading to stables and carriage house at the rear. The

first floor contained a graciously appointed apartment for a well-to-do

tenant; each subsequent floor housed a series of progressively smaller

and less elegant apartments ending with cramped garrets under the

mansard roof. Individually the designs did not have the richness or

plasticity of detail associated with the Second Empire style, but, when

seen in conjunction with other similar buildings, an imposing

streetscape was created. Haussmann's grand approach to urban planning

provided a model for growing urban centres around the world.

(Sanford E. Loring, Principles and Practices of Architecture

[Chicago, Cleveland: Cobb, Pritchard and Company, 1869],

ex. U. Pl. I.)

|

4

Paddington Station and Hotel

London, England

Constructed: 1852-53

Architects: Philip Hardwick and Philip Charles Hardwick

Material: Stone with cement sheathing

With the consolidation of the British railway system, the inferiority of

London terminal facilities became painfully evident and the Great

Western Railway Company's new hotel at Paddington, the first of its

scale, was intended to meet this need. Hailed as a credit to the

achievements of the age, it boasted 150 rooms and aimed at providing

every modern luxury and comfort for the up-to-date tastes of prosperous

travellers.

(Royal Institute of British Architects.)

|

5

Design for the War Office

Whitehall, London, England

Date: 1856-57

Architect: Henry B. Garling

Arranged around an interior courtyard, this building presented four

monumental façades, each swarming with classical orders of great

plasticity. Although never executed, the widely publicized plan

provided a model for public building in the Second Empire style.

(Royal Institute of British Architects.)

|

6

City Hall

Boston, Massachusetts

Constructed: 1862-65

Architects: G.J.F. Bryant and Arthur D. Gilman

Material: Stone

By 1862 Boston had replaced Philadelphia as the artistic and

intellectual centre of the United States; therefore, it is not

surprising that the country's first monumental example of the Second Empire

style should appear in that city. Boston City Hall's compact,

rectangular plan and tightly knit façade may seem conservative when

compared to the sprawling, complex layout of later Second Empire

buildings such as Philadelphia City Hall and the State, War and Navy

Department Building in Washington (Fig. 7).

(Historic American Buildings Survey.)

|

7

State, War and Navy Department Building

Washington, D.C.

Constructed: 1871-87

Architect: Alfred B. Mullett

Material: Stone

Alfred B. Mullett's term as supervising architect to the Treasury

Department (1866-74) covered a period of rapid government

expansion. Of the many federal buildings designed by Mullett all but a

few are in the Second Empire style; for this reason he has been justly

regarded as the leading American exponent of this style.

The largest of these structures, the vast and imposing State, War and

Navy Department Building, consists of a rusticated ground storey forming

the base for the richly columned and pilastered tiers which are

surmounted by a massive mansard roof. The exclusive use of the heavier,

more powerful doric order was perhaps intended to reflect the military

associations of the building. It was constructed of granite which had to

be imported by rail from Richmond, Virginia. This extravagance partially

explains an enormous construction cost of 12 million dollars. This was

an era when government spared no expense to give its structures a

suitable air of governmental authority and dignity.

(Historic American Buildings Survey.)

|

8

Sketches of curved roofs

Designed: 1857

Architect: Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux's pattern book contains one of the earliest references to

the potential picturesque effect inherent in the mansard or broken roof.

These sketches of curved roofs, some of them mansards, may seem simple

in comparison with later more bombastic examples, but they reveal

Vaux's precocious awareness of the growing taste for the picturesque. In

commenting on the sketches, he advised his readers that "some degree of

picturesqueness can always be obtained by the treatment of the roof-lines,

or by the use of verandahs, porches, or baywindows; and these

features, if well arranged, are very valuable in any case, for they help

to supply the variety of light and shade which is so much needed. The

introduction of circular-headed windows, circular projections or

verandahs, and of curved lines in the design of the roof, and in the

details generally, will always have an easy, agreeable effect, if well

managed."

(Calvert Vaux, Villas and Cottages [New York: Harper &

Brothers, 1857], p. 54.)

|

9

French roof suburban villa for L.C. Thompson

Pottsville, Pennsylvania

Designed: 1877

Architect: Isaac H. Hobbs

This elevation for a Second Empire villa is one of many pattern book

designs created by Philadelphia architect Isaac Hobbs and published in

Godey's Lady's Book. Reacting to much modern building that he

considered "outrageous trash", Hobbs insisted that good design must

follow "a law of architectural proportion discovered by us ten years

ago, which I have found unfailing in designing and executing work....

With it, the Mansard-roof ceases to be boxlike in appearance, and houses

have the appearance of being worth twice or three times their cost."

But Hobbs was not interested solely in aesthetics. He devoted his

attention to practical details like ventilation, providing "in our

drawings for air to pass between the rafters from apertures made in the

planciers, which render French roofs very comfortable, they always

having false ceilings, which leave space for ventilation above", and

chimneys which "must be carried up above the house in order that no

eddies of air blowing from any direction shall destroy their

efficiency." Commenting on the success of his pattern book designs from

both an aesthetic and practical point of view, Hobbs notes that "the

intent ... is not only to assist those who may be about to build, but

like the many works of the same character which have been published, to

aid its readers in the cultivation of taste and the love of the

beautiful, that they, too, may read 'sermons in stones'."

(Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. 44, No. 561 [March 1877], p. 291.)

|

10

Toronto General Hospital

Gerrard Street, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1854-78 Demolished

Architect: William Hay

Material: Brick

At first glance, the design for the Toronto General Hospital has little

about it that is Second Empire. The wall surfaces are exceedingly

restrained, lacking the plasticity of the Second Empire style, and the

sparse decorative features such as the pointed doorway with labels above

are drawn from the Gothic Revival tradition. Nevertheless, the

appearance of mansarded towers with their flurry of iron cresting and

flags anticipates the development of full-blown Second Empire designs.

The Scottish architect William Hay (1818-88) had ample opportunity

to be aware of current European fashion for he had trained in the London

office of G.G. Scott, acted as Scott's Clerk of Works for the Anglican

cathedral in Saint John's, Newfoundland in the late 1840s, and returned

briefly to Britain before setting up practice in Toronto in 1852. His

innovative mansarded pavilions would have reached a wide public, for the

proposal was published in the Anglo-American Magazine.

(Anglo-American Magazine, Vol. 4 [Jan.-June 1854],

n.p.)

|

11, 12, 13

Parliament Building and Departmental Buildings

Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ontario

Constructed: 1859-65 Parliament Building demolished: 1916

Architects: Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones (Parliament Building);

Thomas Stent and Augustus Laver (Departmental Buildings)

Material: Stone

Three imposing buildings were arranged in stately U formation on the

spectacular site known as Barrack Hill. The measured, balanced

arrangement of pavilions on the Wellington Street façade of the

Parliament Building, and the individual mansarded towers are early

manifestations of Second Empire design. The boldly picturesque effect of

the reef, revealed in the 19th-century photograph from the rooftop of

the western Departmental Building (Fig. 13), is created by the maze of

ornamental chimneys, iron cresting, towers, and the decorative

multi-coloured shingles.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

14

Government House

King and Simcoe Streets, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1868-70 Demolished: 1912

Architect: Henry Langley

Material: Brick

The lieutenant-governor's residence in Toronto is not only one of the

grandest examples of the Second Empire style in domestic building but it

is also one of the earliest manifestations of this new fashion in

Canada. Even at this early stage the Second Empire vocabulary was fully

developed. The mansard roof, the broken wall planes, the contrasting

colours of stone against brick, and the picturesque roofline accented by

the central tower with iron cresting together create a highly animated

design reflecting the taste for richness and variety of forms.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

15

Custom House

Prince William Street, Saint John, New Brunswick

Constructed: 1877-81 Demolished: 1961

Architects: Department of Public Works; J.T.C. McKean and G.E.

Fairweather, supervising architects

Material: Stone

The Saint John Custom House is one of the largest Public Works'

buildings to be designed in the Second Empire style. The fact that two

of the three ministries to be housed in this building were at the time

headed by New Brunswick representatives — the Honourable Isaac

Burpee, Minister of Customs, and Sir Albert J. Smith, Minister of Marine

and Fisheries — may have had some influence on the decision to

build on such a massive scale. The local press, however, had no

objection to this expensive monument and they proudly boasted that "it

was probably the finest Custom House in America and second to very few

in the world."

Designed in what was referred to as a "free rendering of the Classical

style," it is characterized by a play of convex and straight roof

shapes, a favourite theme for Public Works' designs. Because of the

unusual length of the façade two towers were added at each end to add

visual strength to the corners.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

16

Custom House

Richmond Street, London, Ontario

Constructed: 1872-74 Demolished

Architect: Department of Public Works; William Robinson supervising

architect

Material: Stone

Although the use of the mansard roof places this building within the

Second Empire idiom, the design reflects a conservative trend toward the

established classical styles. The façade composition, with its heavy

rusticated basement pierced by simple round-headed windows, surmounted

by a high, more elaborately articulated first floor and topped by a

lower attic storey, is ultimately derived from the Italian Renaissance

palazzo. Each architectural element is isolated against the flat wall

surface imparting a sense of restraint and clear definition of parts,

unlike the grand sweep of bombastic sculptural detail often found in

Second Empire public buildings. Alterations to the Custom House include

the removal of a central clock tower and the addition of a rear wing in

1885 by local architect, George F. Durand.

William Robinson, the supervising architect of the Custom House,

1872-74, immigrated to Canada from Ireland in 1833, and opened an

architect's office in London in the mid-1850s; in 1857 he was appointed

city engineer. He held this position for 21 years while maintaining at

the same time a successful private practice in surveying, civil

engineering and architecture.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

17, 18

Post Office

Adelaide Street, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1871-74 Demolished: 1960

Architect: Department of Public Works; Henry Langley,

supervising architect

Material: Stone façade, brick sides

The Toronto Post Office marked the beginning of a ten-year reign of the

Second Empire style in federal architecture. Its building history

reveals that this change was not caused by the arrival of T.S. Scott in

1871 as chief architect, but by conscious government policy to create a

new and more progressive public image through its buildings. Although

Scott was responsible for orchestrating this massive programme of

Second Empire building, the stylistic transition actually began prior to

his appointment.

In March of 1870 John Dewe, Post Office Inspector for the Toronto

Division, submitted a set of plans to chief architect, F.P. Rubidge, for

the new Toronto Post Office which he described as "chaste, elegant and

in perfect taste and highly creditable to Mr. Mullett, the architect by

whom they have been drawn." Although these plans have disappeared one

can be fairly certain that they featured the Second Empire style for

their designer, Alfred B. Mullett, chief architect for the Treasury

Department in Washington, was well known as the leading American

exponent of this new fashion (Fig. 7). Mullett was never called upon to

produce any further plans; instead, the commission was given to Henry

Langley of Toronto who had already demonstrated his proficiency in this

idiom with his design for the lieutenant-governor's residence in

Toronto (Fig. 14). The drawing (Fig. 17) probably represents one of

Langley's preliminary proposals which could date as early as 1870. In

the final version, a pediment and coat of arms were added over the main

entrance and the east wing was eliminated. It would appear from this

early design that even in these pre-Scott days the taste for Second

Empire was fully developed.

(Photograph: Public Archives Canada; drawing: Ottawa,

Department of Public Works.)

|

19

Post Office

Elgin Street, Ottawa, Ontario

Constructed: 1872-76 Demolished: 1938

Architect: Department of Public Works; Walter Chesterton,

supervising architect

Material: Stone

The favoured site for the new Post Office was located in what is today

Confederation Square, directly across from the East Block of the

Parliament Buildings. The objection was raised that a building in this

location would injure the view of the Parliament Buildings; however,

Chief Architect T.S. Scott felt "that the façade of the Post Office

could be so made as to accord with, and be erected in the same style as

'public buildings'." While Chesterton's design obviously did not borrow

any of the gothic detailing of the Parliament Buildings, the use of

pavilions, towers, mansard roof and iron cresting is common to both

designs, creating a unified skyline of a lively and picturesque nature.

The unusual tower-like feature over the central pavilion of the Post

Office is unique to the Department of Public Works' Second Empire

designs and was probably intended to give a stronger vertical emphasis

to further harmonize with the nearby Parliament Buildings.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

20

Post Office

Saint James Street, Montreal, Quebec

Constructed: 1872-76 Demolished

Architect: Department of Public Works; H.M. Perrault, supervising

architect

Material: Stone

The Montreal Post Office was one of the finest examples of Second

Empire to be found in Canada. Not only did it feature all the basic

ingredients of high Second Empire style — mansard roof, pavilion

massing, robust classical ornamentation and picturesque roofline —

but it coordinated this profusion of detail into a tightly organized

composition controlled by the massive corinthian columns and pilasters

two storeys high. The ground floor was defined by short piers and

columns which provided a sturdy base for the grand projecting portico

above. This use of freestanding forms and the resulting effects of light

and shade gave the façade its strong feeling of three-dimensionality and

monumentality.

Situated on the prestigious Saint James Street, the heart of Montreal's

financial and business community, the Post Office had to compete with

nearby impressive buildings like the Bank of Montreal of 1848 by John

Wells. The federal government, intent on making its presence felt,

chose, for the Post Office, a prominent site and sumptuous manner that

would equal or surpass its neighbours.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

21

Custom House

Front and Yonge Streets, Toronto, Ontario

Constructed: 1873-76 Demolished: 1919

Architect: Department of Public Works; R.C. Windeyer,

supervising architect

Material: Stone

The Toronto Custom House was one of the most unusual and distinctive

buildings to be erected by the federal government under T.S. Scott's

reign as chief architect. The full bulbous form of the convex mansard

roof, the bevelled corners and the free interpretation of the classical

detail together produced its unique architectural character. The façade

of the Toronto Custom House was organized in the typical grid system of

pilasters and entablatures; however, the intricate stone detail with

carved heads, tall ornamental pediment and decorative bands had an

unusually organic and baroque character. To modern taste this building

would perhaps seem overdone but at the time of its completion this

bombastic structure was well suited to Toronto's mood of self assurance.

The city was extremely proud of this building and it was described in

glowing terms as "a palace not unworthy of the commercial interests of a

great and progressive city."

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

22

Post Office

Government Street, Victoria, British Columbia

Constructed: 1873-74 Demolished

Architect: Department of Public Works; Benjamin W. Pearse, resident

engineer

Material: Brick

The Victoria Post Office was the first federal building to be erected in

the newly confederated province of British Columbia. Although the

Department of Public Works was not generally known for its frugality, in

this case it seemed intent on keeping the building costs down. Except

for some modest flourishes around the door and the quoining at the

corners and windows the design displays none of the refinement of detail

usually found on even the smallest of public buildings in the east. The

functional nature of the design was described by the architect, Benjamin

Pearse. "The building, though not aesthetically beautiful, is of a very

substantial character."

Benjamin W. Pearse had been employed as the Surveyor General under the

colonial government and in 1872 was hired by the Department of Public

Works as its resident engineer, a post which he held for many years.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

23

Custom House

1002 Wharf Street, Victoria, British Columbia

Constructed: 1873-75

Architect: Department of Public Works

Material: Brick

As originally planned all government offices in Victoria were to be

housed in the Post Office building (Fig. 22) but it soon became apparent

that a separate building would be required to accommodate the Custom

House and the offices of the Departments of Inland Revenue and Marine

and Fisheries. In appearance the Custom House resembles the Post Office,

although the façade has an even greater simplicity. While one cannot

pretend that the Custom House and Post Office were among the better

achievements of the Department of Public Works, they nevertheless had

an important effect on local architecture — witness the group of

Second Empire buildings such as the Victoria City Hall (Fig. 33) built

in Victoria in the late 1870s.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

24

MacKenzie Building

Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario

Constructed: 1876-78

Architect: Department of Public Works; Robert Gage, supervising

architect

Material: Stone

The MacKenzie Building, named after Prime Minister Alexander MacKenzie,

was built to house the administrative and educational functions of

Canada's first military college which opened in 1876. The 1877 annual

report of the chief architect (T.S. Scott) for the Department of Public

Works describes the building as "plain in design and substantial in

character. The outer walls are built of local limestone with cut stone

quoins, plinth, strings and drawings to windows and doors; the stonework

is supplied and cut at the Kingston Penitentiary." Consistent with

federal building during Scott's term as chief architect the design is of

the Second Empire style although not as grandly elaborate as his other

large public buildings. Perhaps it was felt that more sober

interpretation would better harmonize with the existing buildings on the

square and at the same time give a fittingly military appearance to the

structure.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

25

Post Office, Custom House, Inland Revenue Building

Saint George Square, Guelph, Ontario

Constructed: 1876-78 Demolished

Architect: Department of Public Works

Material: Stone

As was often the case for smaller urban centres, the plans for this

building were prepared by Department of Public Works' staff in Ottawa

instead of being contracted to a local designer. Nevertheless, this

absentee architect must have had a good understanding of the local

architectural character in order to produce a design which harmonized so

successfully with its environment. Except for the elaborate brackets

under the small tower and the ornate balcony over the main door, which

together accent the central entrance, the decoration is quite severe and

restrained by Department of Public Works' standards. The emphasis of the

design lies with the surface texture of local limestone masonry whose

sturdy quality is so characteristic of buildings in Guelph.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

26

Architectural drawing of the Post Office, Custom House and Inland

Revenue Building

Richelieu Street, Saint-Jean, Quebec

Constructed: 1877-80 Demolished

Date of Drawing: 1878

Architect: Department of Public Works

Material: Brick

The plans for the Saint-Jean Post Office were drawn up by Department

of Public Works' staff in Ottawa with on-site supervision provided by

the Montreal firm of architects, Alex C. Hutchison and A.D. Steele.

Although these central office designs did not follow any standardized

formula, the stamp of the Ottawa office can often be identified by

several decorative motifs. For example, the near contemporary Guelph

Post Office (Fig. 25), despite a difference in material and scale, shows

the same central focus with raised tower, ornamental balcony over the

main doorway, narrow doubled string courses which define the floor

divisions and link the ground storey windows, and similar cornice motif

with brackets interspaced by rectangular panels.

(Ottawa, Department of Public Works.)

|

27

Architectural drawing of the Post Office and Custom House

Pitt Street, Windsor, Ontario

Constructed: 1878-80 Demolished

Architect: Department of Public Works; William Scott, supervising

architect

Material: Stone, two sides; brick, two sides

The façade composition of the Windsor Post Office and Custom House, with

its central round-headed doorway, second floor balcony and slightly

projecting pavilion form in the mansard roof, is very similar to the

design of both the Saint-Jean and Guelph federal buildings (Figs. 25,

26). Although the Windsor building was conceived by local

architect-builder William Scott, the consistency of these motifs would

suggest that the chief architect's office in Ottawa exercised

considerable control over the final design. The Windsor Post Office and

Custom House, however, is set apart from the typical Department of

Public Works' design in its subtle gothicizing note created by the

slightly pointed arches of the radiating voussoirs over the ground flor

windows.

(Ottawa, Department of Public Works.)

|

28

Parliament Building

Kennedy Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Constructed: 1881-83 Demolished: 1920

Architect: Department of Public Works; J.P.M. Lecourt,

supervising architect

Material: Brick with stone trim

The erection of a permanent legislative assembly for the province of

Manitoba became the responsibility of the federal government. The fact

that the plans were prepared in Ottawa perhaps explains why the

contractors for the building were the Ottawa-based firm of J. & P.

Lyons & Company. The Parliament Building bears the standard

trademarks of Department of Public Works' design at this time, including

organisation of the façade into pavilion units and a variety of

mansarded roofs and towers. The sessional papers state that "the style

of architecture adopted is Italian, modified to suit the requirements of

the climate." Although the Parliament Building does not have as much

decoration as other governmental buildings in the Second Empire mode, it

has a grace and dignity due in large measure to the rhythmic play of

semicircular and segmental openings. In accordance with its primary

function, the Parliament Building housed an impressive legislative

chamber surrounded by galleries on three sides. It apparently met with

local approbation as witnessed by one account which calls it "a

handsome structure, and equal, if not superior, to any Provincial

building in the Dominion."

The designer of the Parliament Building, J.P.M. Lecourt, began his

career in Quebec City, moving to Ottawa in the mid-1860s to become

staff architect for the Department of Public Works. For over a decade he

monopolized Winnipeg's federal architecture after being transferred to

this western city during the hectic building boom of the early 1880s.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

29

Parliament Buildings

Dufferin Avenue, Quebec, Quebec

Constructed: 1877-87

Architect: Eugène Taché (exterior); Jean-Baptiste Delorme and

Pierre Gauvreau (interior planning and supervision)

Material: Stone

It would be tempting to ascribe the use of the Second Empire style to an

expression of French Quebec nationalism were it not for the general

popularity of this style in North America and the strong similarities of

Quebec's Parliament Building with other public institutions in Canada.

In many ways Taché's design is really a classicized version of Fuller

and Jones' central block for the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. This

parallel is particularly apparent in the main towers, both characterized

by their tall slender form and similar turret-like details called

bartizans. Nevertheless, Taché clearly meant to express a cultural link

with France. Like the Louvre in Paris, The Quebec Parliament Building is

composed of wings that enclose a central courtyard and the practice of

dedicating the pavilions to important historical figures like Jacques

Cartier, Champlain and Maisonneuve is borrowed from its French

counterpart

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

30

Legislative Building

750 Queen Street, Fredericton, New Brunswick

Constructed: 1880-82

Architect: James C. Dumaresq

Material: Stone

The need for a new Legislative Building in New Brunswick was regarded as

an opportunity to provide the province and the country with a fittingly

grand architectural symbol to the province's spirit of self-confidence.

These ambitions were well expressed in an article of 31 March 1880 in

the New Brunswick Reporter: "We hope that the House will vote

such an amount as will enable the Government to erect a structure that

will not only adequately provide for both houses of the Legislature, Law

Courts, Library, etc., but one that will be a credit in point of design,

elegance and architecture to the province ... handsome as well as

substantial, and commensurate with the progressing spirit of the age in

which we are living." With these requirements in mind it is not

surprising that James Dumaresq's winning design should be in the

expensive and prestigious Second Empire style; however, elements such as

the cupola and pedimented frontispiece reflect a conservative leaning

toward the established classical styles which were so well entrenched in

local architectural tradition.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

|

|

|

|