|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The B.C. Mills Prefabricated System: The Emergence of Ready-made Buildings in Western Canada

by G. E. Mills and D. W. Holdsworth

The Demise of the System

Despite the widespread enthusiasm of firms, institutions and

individuals for the B.C. Mills ready-made system, its period of

production was short-lived. By 1911 the panels were no longer listed

among the firm's line of products. Coincidentally, the last of the

prefab banks, erected in Ladysmith, Vancouver Island on 21 June 1911,

marked the end of the Bank of Commerce's major phase of western branch

expansion.

Previous prefabricated building industries had been dependent on

fragile and transitory economic conditions. The B. C. Mills system was

no exception, it blossomed during a period of rampant population growth

which locally based lumber and building industries were not yet geared

to meet. By 1908, however, shifts were beginning to occur which were

reflected in the records of the firm. Although 1904 to 1907 were boom

years for the British Columbia lumber industry, a recession in profits

began to set in by 1908 due to increased competition and a corresponding

decline in retail prices. This competition included a number of

sectional building systems which were marketed by Vancouver firms

after 1905 none, however, seriously challenged the B. C. Mills line in

design or volume of production.1 In his report for 1908,

general manager John Hendry of B. C. Mills declared that although the

volume of business had continued to rise, prices had dropped markedly

over the previous year, particularly in the domestic trade. The

company's policy in the face of this less favourable climate was "a

curtailment of operations and expenses, as far as possible, and

refraint from pushing trade that could only be done at a loss."2

But whereas the prices of standard lumber products were forced down by

market competition, the cost of prefabricated buildings crept steadily

higher from the initial 1904 prices, thus eroding their competitive edge

over locally built housing. Nevertheless, in 1908 the firm deemed it

appropriate to spend several thousand dollars on an exhibit at the

Calgary Exhibition, indicating that prefabs were not yet considered

among the firm's liabilities.3

Perhaps a more direct reason for the eventual dropping of the prefabs

in 1910 lay in Hendry's personal financial commitments. After 1907 he

had become increasingly involved in railroad and land speculation.

Possession of the Vancouver, Westminster and Yukon Railroad franchise,

which offered the only feasible route into Vancouver apart from the

Canadian Pacific, made him the recipient of a succession of overtures

and offers from railroad companies. Consequently after 1908, Hendry

regarded his milling interests increasingly in terms of their real

estate value as strategic waterfront properties rather than as an

expanding industry. In correspondence with his secretary, William McNeil, he

expressed a recurring desire to liquidate his mill assets and remove

himself entirely from the lumber industry.4 Although the firm

did not pass out of his hands until 1913, general policy during the last

years of Hendry's management appears to have reflected his declining

enthusiasm for the lumbering aspect of his holdings. Increasing

competition and declining prices undoubtedly encouraged his

outlook.

It is not surprising therefore that when approached in 1910 by a

newly formed firm, the Prudential Builders Limited, Hendry agreed to

turn over the rights to the prefab system on a royalty basis. Edwin

Mahony left the B.C. Mills Timber and Trading Company to assume the post

of general manager of Prudential Builders. Evidently the board of

directors of this company considered the market for prefabricated

housing to be far from closed. In a prospectus to shareholders they

confidently announced

The Company has acquired the rights to manufacture on a royalty

basis, the most improved and modern sectional buildings ever invented.

We have in operation one of the finest wood-working factories in the

Dominion for the manufacture of these sectional buildings, and our

special equipment enables us to secure a large share of this very

profitable business. . . . These buildings will be shipped

throughout the Western Provinces and sold to incoming settlers on easy

terms.5

Prudential Builders was in fact representative of a new phenomenon

occurring in western Canada. Like the older B. C. Mills, Timber and

Trading Company, the firm owned its own timber rights and saw-mill, in

addition to a large house-building factory located at the corner of

Manitoba and Dufferin streets on the south side of Vancouver's False

Creek. But unlike B. C. Mills, this firm was specifically geared to the

mass production of popularly priced housing rather than components and

lumber products. Its lineage lay not in the old-style saw-mills of the

lower mainland, but in the Prudential Investment Company, one of the

numerous investment and loan companies emerging in the highly

speculative building climate of Vancouver. Marketing of the firm's

houses was conducted through a subsidiary, the National Finance

Company.6

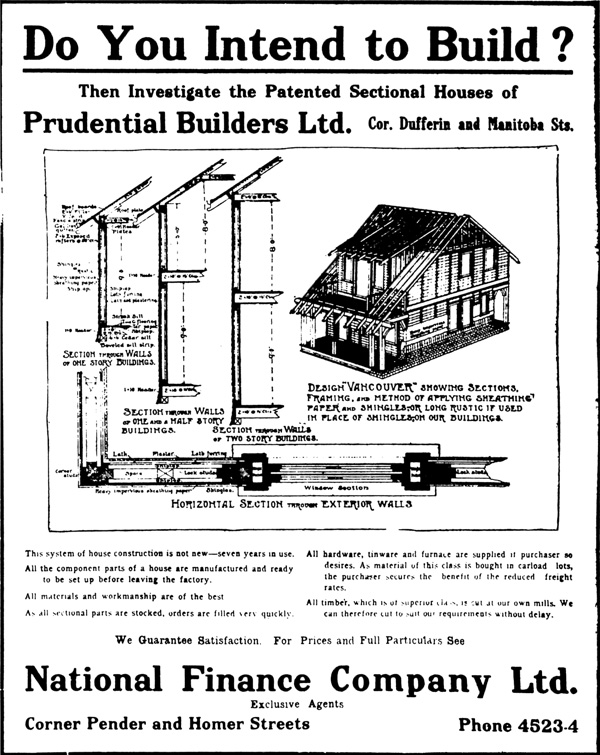

22 Prudential Builders, inheritors of the prefabricated system in 1910,

attempted to adapt it to larger California-style bungalows. Note this

advertisement's concern with stressing the maturity and reliability of

the sectional system ("in use for 7 years"). Many styles were

advertised, but this design, "Vancouver", typified the predominant

two-storey house built in large areas of Vancouver during this period.

(Province [Vancouver].)

|

Although Prudential Builders initially intended to continue tapping

the rural frontier market for prefabricated housing, the newly settled

rural regions, they soon altered their plans. They attempted instead to

apply the sectional system to the continually growing urban market in

the form of subdivision housing. At this point a conflict arose between

Mahony, the system's inventor, and the executives of the firm over the

type and location of such developments. Mahony maintained that his

system would be best applied initially to small homes on the outskirts

of Vancouver which would be inexpensive and readily marketable to

working-class buyers.7 The firm instead elected to apply the

system to the construction of larger California-bungalow style homes on

a tract of land adjacent to Shaughnessy Heights, the most fashionable

residential section of the city. Inspired by a development in Los

Angeles, the project was named Talton Place after the firm's president,

Thomas Talton Langlois. It is believed to have been the first attempt at

mass-produced subdivision housing in the city.8 The first

houses were prefabricated at the firm's plant at False Creek, then

reassembled on site. Mahony's fears were soon borne out, however, it was

found that the use of the panels inflated the cost of the houses beyond

those of other firms. Prudential Builders decided to abandon use of the

system and built the remainder of their houses in the orthodox

baloon-frame manner, with the intention of marketing them in both

Vancouver and western Canada.

This proved increasingly difficult to do, as the industrial bases in

large prairie centres such as Calgary and Winnipeg were now capable of

supporting similar firms geared to mass-produced house

manufacturing.9 Although this terminated the demand for

ready-made structures, Vancouver's role as a major lumber supplier for

the prairies continued, as did its influence on prairie building

designs.10 Edwin Mahony left Prudential Builders within a

year of their abandonment of his sectional building system,11

and an interesting phase in western Canada's architectural development

came to an end.

|