|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The B.C. Mills Prefabricated System: The Emergence of Ready-made Buildings in Western Canada

by G. E. Mills and D. W. Holdsworth

Invention, House Designs and Initial Marketing

The shortage of lumber products on the Canadian prairies in the years

after 1900 was particularly opportune for Vancouver and British

Columbia. Lumber-mills geared to the foreign export trade had been

operating in the Vancouver region since the mid-1860s. Timber in the

immediate area acquired a reputation in foreign markets for its

remarkably large size and high quality. Even after the establishment of

Vancouver as west-coast terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886,

the trade of that city's mills remained primarily geared to export

markets. This trend was gradually supplemented by a growing local market

as the city and its neighbouring communities experienced their initial

construction booms. With the growth of trunk lines and settlement both

on the prairies and in the British Columbian interior during the 1890s,

a complementary market emerged, capable of absorbing the rough cuts,

shingles and milled products unmarketable in the export trade, and

Vancouver's role as a manufacturing and distribution centre rather than

merely a shipping depot commenced.1 Saw- and planing-mills

were quickly consolidated and diversified to exploit this new source of

trade.

The leader in this trend was the British Columbia Mills, Timber and

Trading Company. It was formed in 1889 by the amalgamation of three

large saw-mill companies located on the British Columbia lower

mainland: the two Royal City Mills founded and owned by John Hendry at

New Westminster and on False Creek in Vancouver, the Hasting Mill on

Vancouver's waterfront, and the Moodyville Mill across Burrard Inlet in

North Vancouver. Under the aggressive management of Hendry,2

the company rapidly expanded its assets to include logging railways a

fleet of steamers and vast timber rights in British Columbia. By 1905

the four mills had a daily capacity of 500,000 feet of lumber, 200,000

shingles, 600 doors, and 100,000 feet of mouldings, and employed a staff

of over 2,000 people. B.C. Mills termed itself "the largest lumber

manufacturing establishment in Western Canada or on the Pacific Coast,

and one of the largest in the world."3

1 Design A, B.C. Mills Settlers' series.

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of

Patented Ready-made Houses. [Vancouver, 1905].)

|

During the early 1890s a large amount of the firm's production was

shifted from export to domestic trade. The Hastings Mill division on the

Vancouver waterfront was partially altered for this purpose in 1891

while the False Creek branch of the Royal City Mills was converted to

domestic trade in the following years. These changes were consistent

with president Hendry's long time interest in tapping the potential

markets of the Canadian Northwest. As early as 1874 he had travelled

east to Winnipeg to investigate the potential demand for west-coast

lumber. Such a market appeared ripe to him by the mid-1890s, and a

Winnipeg office was opened in 1900. The firm's line of building

products, ranging from milled lumber to sashes, doors and decorative

mouldings, was subsequently distributed throughout western Canada.

2 Edward Caton Mahony, Royal City Planing Mills manager and inventor

of the patented sectional wall system used in the B.C. Mills prefabs.

(R. E. Gosnell, A History of British Columbia, Lewis, Victoria,

1906.)

|

The idea of adding a selection of prefabricated buildings may be

viewed as a logical step in rounding out the firm's already extensive

line of products. In fact, B.C. Mills appears to have been initially

motivated more by desires for increased mill efficiency than by

grandiose designs for revolutionizing the housing industry. Royal City

Mills manager Edwin C. Mahony, a veteran lumberman, began experimenting

with a system of panelled wall construction as a means of utilizing

excess short ends of lumber which were being discarded as waste.

Previous attempts at marketing prefabricated sectional houses as

temporary accommodations had, as previously stated, proven unsuccessful

in western Canada. In fact preceding structures had acquired a notoriety

for being flimsy, draughty and hard to heat which made marketing

prospects rather grim. So Mahony was faced not only with the problem of

devising a system which would provide weather resistance and durability,

but also with overcoming a well-entrenched stigma attached to such

structures.4 After a year's experimentation, he arrived at a

solution to the structural problems unique enough to warrant a patent,

which was issued to him in January 1904.

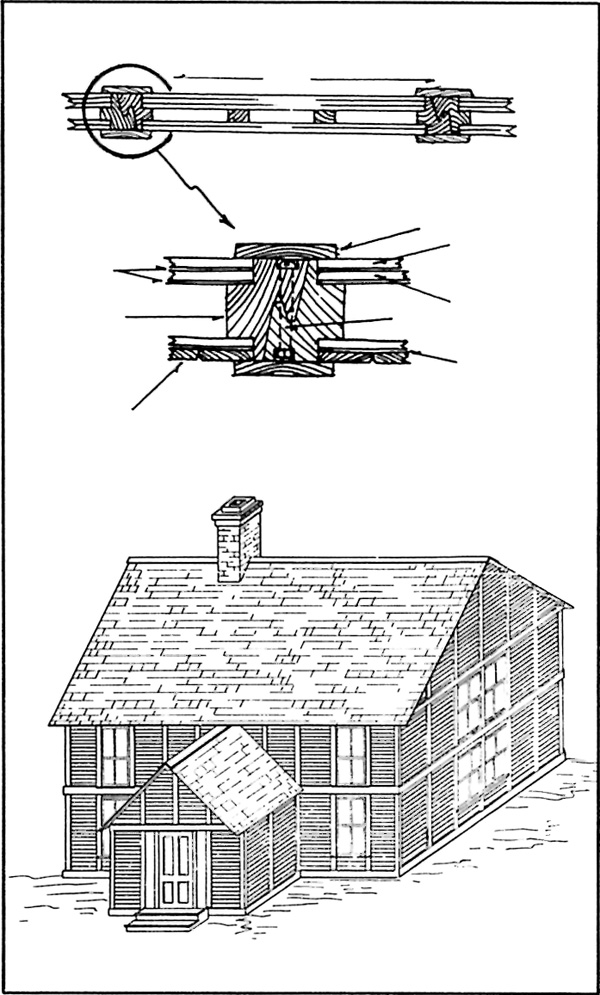

Mahony produced a panel incorporating a series of layers of wood and

tarpaper separated by an air space. This unit was calculated to offer

adequate insulation against the western Canadian climate. Laminated

panels were not actually a new concept, although Mahony believed them to

be so. Darnall notes the invention of interlocking sandwich panels by a

Lorenzo Forrest of Minneapolis in 1884.5 Mahony's system

differed, however, in the greater number of veneers and the use of a

moulded weather-tight joint by which successive panels could be linked

together, then bolted (Fig. 3). Windows and doors were incorporated in

panels which likewise slid together. Panels were further locked in

position by morticed sills at both the floor and eaves level as

additional protection against heat loss. It was the inclusion of these

moulded joints which marked the chief innovation in Mahony's system. The

inventor made provisions for additional storeys which could be stacked

on top of each other using additional moulded sills, although additional

storeys were rarely used. He also provided for prefabricated roofs and

floor sections in his patent, although these sections were not

incorporated in production models; they offered precut studding, rafters

and joists instead.

3 Components of prefab panels and house from 1904 patent.

Upper, cross-sections showing panel components and sectional

joint; lower, no indication of the distinctive designs which

characterised the B.C. Mills prefabs is evident in Mahony's initial

patent illustration of the system's application.

(Canada. Dept. of Agriculture, Parent Office

Record, 1904, No. 85, 101, 1 January 1904.)

|

The exteriors of Mahony's prefabs were characterized by narrow

clapboard veneers broken at three- or four-foot intervals by vertical

battens that covered the panel joints. In some cases a veneer of cedar

shingles was added, thereby completely masking any indication that the

building was in fact a "knockdown." The inside veneer of the panels was

offered with either tongue-and-groove cedar or lathing for plaster

walls.

In his letter of patent, Mahony left no doubt that his system was

intended for the traditional prefabricated building market, the recently

arrived settlers of remote agricultural regions.

My invention relates to the construction of knockdown houses

especially designed for the use of settlers in a comparatively new or

undeveloped country, and is intended to meet the requirements of such a

class by providing a framed house the erection of which does not require

the service of skilled carpenters or tradesmen, but that can be put

together by the settler himself in less time than it would take to build

one in the usual manner, and that when finished is superior in its

weather resisting qualities, appearance and comfort to the best class

of house usually built by farmers or miners.6

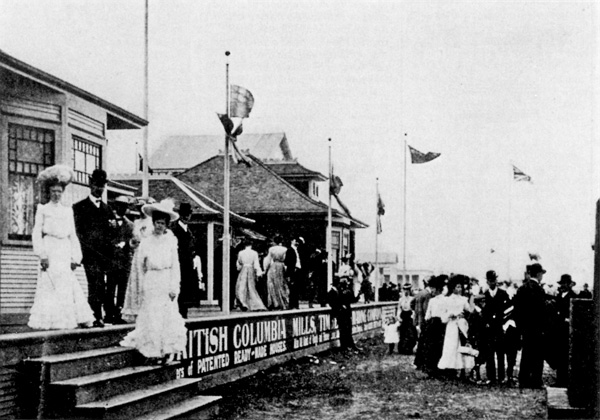

Having overcome the technical problems related to prefabricated

sectional houses, Mahony next confronted the problem of gaining public

acceptance for such a system. The first step was the production of a

series of small one-storey hip-roofed structures, five of which were

shipped to Winnipeg to be displayed at that city's annual exhibition in

the summer of 1904 (Fig. 4). The intention of this display was both to

demonstrate the system's weather-resisting properties and quality of

materials and construction, and to gauge public response. The timing of

the display could not have been better. The city of Winnipeg was then on

the crest of a phenomenal period of growth.7 The demand for

housing among incoming migrants far outstripped production, resulting

in a desperate demand for housing of any kind. A system of ready-made

structures which eliminated the need for local lumber and carpenters

appeared to members of the local press to offer a ready solution to the

existing shortage.

There has been nothing on the fair grounds in the last weeks that

has attracted more attention than the cottages erected of British

Columbia lumber. There is a fascinating sound about a house built to

order, for the very reasonable prices quoted. The cottages shown are

very pretty and convenient, and in addition you can order your house

laid out any way you please, within moderation.

The fierce demand for some place to live made visitors to the fair

keen to visit these houses and see their possibilities. Even at the

present exhorbitant figures charged for putting in foundations, there

would seem a possibility of getting an abiding place within the reach of

people in very moderate circumstances, while for the settler on new land

these cottages certainly solve a knotty problem.8

4 Winnipeg Fair (July 1804) marked the first public display of the

B.C. Mills prefabs and the beginning of their distribution on the

prairies.

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of Patented Ready-made Houses

(Vancouver, 1805].)

|

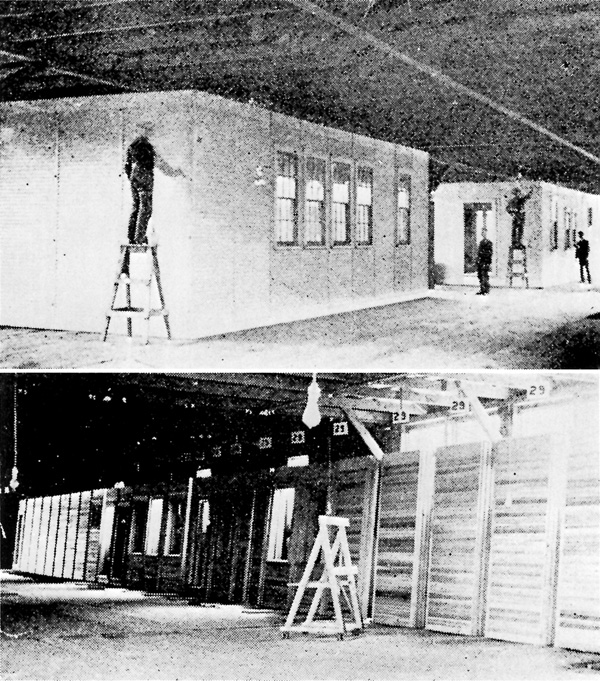

A similar display at the Royal Agricultural Exhibition at New

Westminster, British Columbia, in the fall of 1904 also met with public

approval. Encouraged by brisk sales of these initial models, both on the

prairies and in British Columbia, and by a demand for larger versions,

the B.C. Mills Timber and Trading Company began an expansion of its

facilities at the False Creek Royal City Mill. A storage barn was built

capable of housing enough panels for 50 houses along with a large

fitting and erecting shed where up to six buildings could be

preassembled and painted prior to packaging and shipping. In the fall of

1905 a catalogue was published offering a greatly expanded range of

house models. There were in fact two distinct series marketed. A

selection of small inexpensive huts labelled the "Settlers' Series" was

clearly aimed at the traditional prefab market, the newly arrived

residents of isolated rural areas requiring temporary accommodation, or

artisans desiring quickly built quarters in urban centres. For as little

as $100 one could purchase a 12 ft. by 12 ft. one-room cabin, prepainted

and complete with wooden footings and a galvanized iron chimney. Three

additional designs were offered. ranging up to a three-room 16 ft. by 20

ft. cabin featuring sectional interior partitions and priced at

$200.

5 a, "Portion of fitting and erecting sheds

showing the walls of a school house and cottage in place, and receiving

their primary coat of paint prior to shipment." (B.C. Mills, Timber and Trading Company, Ready-Made

Houses: A New System of House Construction [Vancouver,

1906].) b, storage warehouse for

ready-made house sections at Royal City Planing Mills. (B.C. Mills. Catalogue of Patented Ready-made

Houses [Vancouver, 1905].)

|

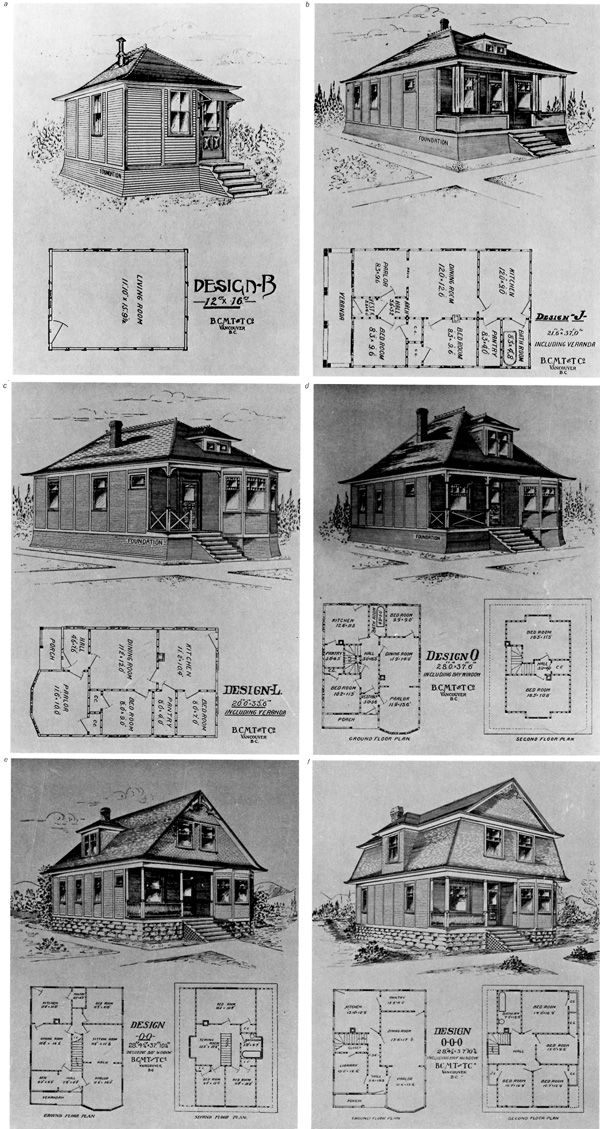

A second group, labelled the "Townhouse Series," was offered to a

broader market. This series, presenting a basic selection of 15 designs

ranging from a 4-room 21 ft. by 29 ft. one-storey cottage up to

4-bedroom 1-1/2- and 2-storey homes, was in effect offering the

prospective buyer a permanent residence at prices competitive to if not

cheaper than those of locally built structures.9 Prices

ranged from $400 to $785 in the initial area catalogue, prompting claims

of savings of up to 40 per cent over the cost of equivalent structures

built on site. Standard designs could be enlarged or altered to suit

individual taste by juggling the number and location of panels. Interior

layouts were flexible, apart from the location of staircases (Fig.

6).

6 a-f, Sample of designs and floor plans from B.C. Mills

Catalogue of Patented Ready-made Houses (Vancouver 1905). (click

on image for a PDF version)

|

Considerable attention was given to the external appearance of all

models; as they were being marketed in competition with locally

produced structures, they had to be visually attractive in order to

overcome general suspicions regarding their quality and durability. All

models featured standard B. C. Mills sashes, doors, rain gutters and

moulding trims. Another standard feature was their bell-cast roofs,

deemed "an improvement on the hard effect of the usual straight line

finish seen in most wooden houses." On cottages in the Townhouse Series,

a decorative dormer window was installed on the hipped roof, "adding

much to the tastefulness of these natty residences." Additional features

were bay windows on the front façade of most models, along with full or

partial verandahs, "nicely arranged and related so as to produce a fine

impression on the eye."10 The largest two-storey designs also

featured a distinctive gambrel roof with decorative eaves trim. Most of

these stylistic features were in fact borrowed from popular styles

prevalent in the Vancouver area around the turn of the century; the

combination of such features, along with the battened wall system and B.C.

Mills standardized products, gave them a distinctive appearance which

was, and still is, readily apparent to the alert observer.

7 The firm's expanded range of townhouses was first displayed at the

New Westminster Dominion Exhibition, 27 September to 7 October 1805.

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of Patented Ready-made Houses [Vancouver,

1805].)

|

8 Two design O prefabs. The Saskatchewan Elbow and Wheat Lands Co.,

Caron, Saskatchewan. "The sod house in the centre of the group is

representative of the settlers' early habitations,

and was occupied by the builders during the erection of these

buildings."

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of Patented Ready-made

Houses (Vancouver, 1905].)

|

One of the major selling points was, of course, ease and speed of

construction. Each house was preassembled and painted, then individual

pieces were numbered prior to packaging for shipment. Using an enclosed

book of instructions, the purchaser could erect his home in several days

without the need of skilled assistance.

Every section is numbered. The sill of the house is laid, then

beginning with, say, number 2 section, each is fitted into the place

indicated by a corresponding number. If a door is desired in a certain

place or a window in another, the section with these already in may be

placed to suit.... Individual taste can easily be accommodated in every

respect. As every section fits, having been tried before leaving the

factory, there is no mistake to make, as the directions are absolute.

When the sides and end walls are in place, according to plan, the roof

is put on, each part necessary having been cut and ready for

position.11

A selection of these new designs was displayed at a second trade fair

held in New Westminster, British Columbia, in the fall of 1905. The

five-building display was an immediate success. A local clergyman

purchased three of them for his congregation, and the local press gave

highly favourable reviews on the merits of the system. Subsequent rapid

sales in the greater Vancouver area and lower Fraser Valley towns

suggest that they were considered as economical and attractive

alternatives to conventionally constructed houses even in lumber-rich

areas. A dealer in Chilliwack advertised,

The very best houses in Chilliwack are the only houses that will

compare with Ready-Made Houses in design, quality, and warmth.... At the

present prices of lumber I believe these houses are cheaper than can be

built in the usual way.12

Distribution was channelled through the B.C. Mills head office and

Royal City Mills in Vancouver, and the branch office in Winnipeg. Houses

were shipped, from one to six per boxcar (depending on size), to local

agents. This policy made them attractive to firms or individuals wishing

to purchase in quantity. In Caron, Saskatchewan, the Saskatchewan Elbow

and Wheat Lands Company purchased a number of hipped roof models to sell

as replacements for settlers' initial sod houses. In urban centres,

particularly Vancouver and Winnipeg, there were frequent instances of

clusters of small models being erected on 25-foot lots for rental

purposes. A Polish Catholic priest in Winnipeg's north end purchased a

group of 17 such models for members of his parish.

The firm took pains to stress that, rather than restricting the scope

of individual taste. the system offered the purchaser an almost

limitless number of possible variations. Edwin Mahony undertook to

demonstrate this by building himself an eye-catching home in

Vancouver's fashionable West End district in 1905 (Fig. 9), which a

local writer touted as "an example of the perfection to which this

modern method of construction has been brought. It is attractive. unique

and handsome, and shows that individuality of taste has the fullest

scope."13 In fact, although floor plans were modified to suit

individual needs, most customers appear to have contented themselves

with standard Townhouse designs, varied only by occasional alteration

through the use of additional panels.

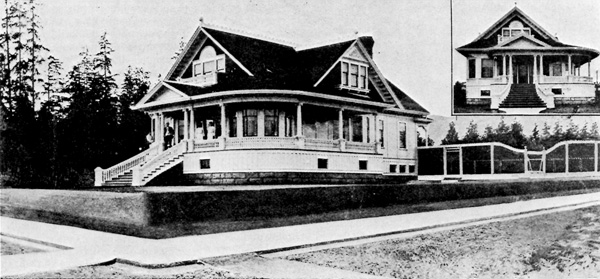

9 E. C. Mahony's prefabricated home on Comox Street, Vancouver

(demolished).

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of Patented Ready-made

Houses (Vancouver, 1905].)

|

|