|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 14

The B.C. Mills Prefabricated System: The Emergence of Ready-made Buildings in Western Canada

by G. E. Mills and D. W. Holdsworth

Commercial Applications and Distribution

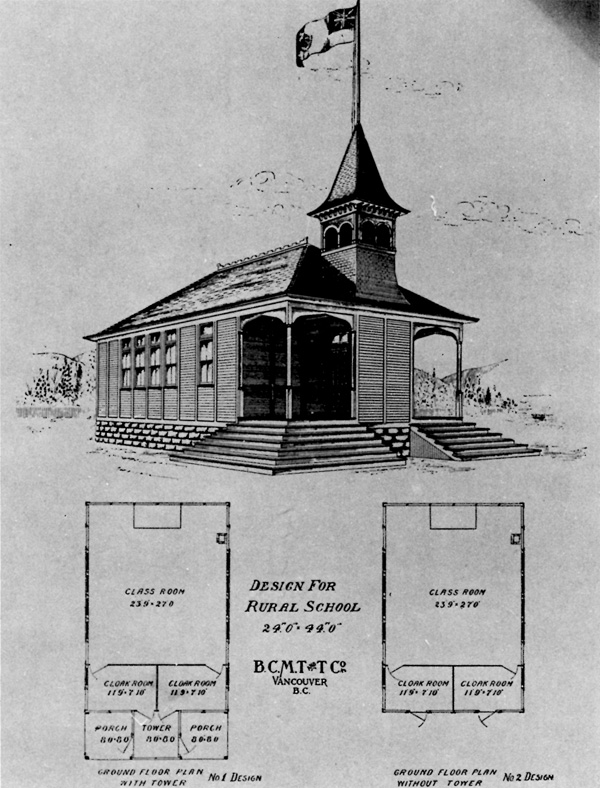

The flexibility of the system lent itself to wider non-residential

applications. B. C. Mills marketed a schoolhouse series, small one-room

structures with optional bell towers which were sold in both Manitoba

and British Columbia.1 Urban applications were made in

Vancouver and New Westminster, the former employing them as portable

classrooms to accommodate rapidly growing enrolments, and the New

Westminster board commissioning one for administrative purposes. Several

of the Vancouver buildings are still in use at the present time.

10 Schoolhouse design from 1805 catalogue. Multiple use of standard

window sections provided light for the schoolroom. These structures were

offered with or without the bell tower.

(B.C. Mills, Catalogue of

Patented Ready-made Houses [Vancouver, 1905].)

|

At least two churches were built from B. C. Mills panels in the

Vancouver area. One, the Robertson Presbyterian Church in the city's east

end, survives although a non-prefabricated front wing was later added

to the original 1908 structure.

At Rock Bay, the headquarters of the B. C. Mills, Timber and Trading

Company logging operations on the north end of Vancouver Island, two

Townhouse Series houses were built. One served as the camp's hospital,

run by the Victorian Order of Nurses (later moved to Union Bay,

Vancouver Island). Several bunkhouses were also constructed from the

panels at this location. A Settlers' Series hut was employed as the

first post office at Ocean Falls, B. C. in 1908, while a similar

structure served as part of the initial sanitorium complex at Kamloops,

B.C.2

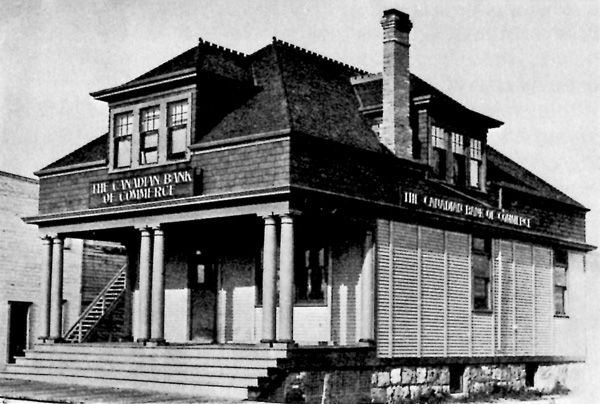

Just as Mahony's personal home was constructed to demonstrate the

system's flexibility for residential use, the offices and outbuildings

at the firm's mill sites in Vancouver became models to demonstrate its

potential commercial applications. The main office of the B. C. Mills,

Timber and Trading Company at the foot of Dunlevy Street on Vancouver's

waterfront and the office at the Royal City Mill at the head of False

Creek, both erected in 1905, were impressive hipped-roof structures with

porticoed full verandahs. They were calculated to impress the public

with "to what variety the sections may be put, and how any particular

architecture may be carried out, without adherence to any one or two

[standard] designs."3 A massive two-storey stable on the B.C.

Mills site served similarly to demonstrate possible agricultural

applications. Both the office and barn on this location long survived

the company's demise. The barn remained intact until the summer of 1973

when it was destroyed by fire; the office remains a familiar landmark,

having served successively as National Harbours Board office and

Seaman's Mission.

11 Built in 1905 as the B.C. Mills Hasting Mill general office, this

structure was possibly the most elegant example of the prefabricated

system's potential. A similar building was erected at the firm's Royal

City Planing Mills branch in Vancouver.

(H. J. Boam, British

Columbia: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries and Resources,

Sells, London, 1914.)

|

12 The British Columbia Telephone Company exchange, Aldergrove, B.C.,

30 miles east of Vancouver. The firm erected six prefab exchanges in

Fraser Valley towns prior to 1910.

|

13 Refreshments room, Canadian Pacific Railway station, Mission City,

B.C. (demolished).

(British Columbia Provincial Archives.)

|

The adaptability of the system to commercial buildings was quickly

exploited by a variety of firms. Artisans and shopkeepers employed

slightly modified standard house designs for shops and offices. The

British Columbia Telephone Company erected a half-dozen hipped-roof

models in the Fraser Valley towns of Eburne, Ladner, Haney, Cloverdale,

Aldergrove and Agassiz as local exchanges.4 The Canadian

Pacific Railroad, the chief initial means of distributing the prefabs,

is known to have purchased several for crew accommodation and

maintenance facilities.5

Chartered banks were undoubtedly B.C. Mills' best commercial

customers for prefabs. Banking in western Canada was a highly

competitive and speculative field during the first decade of this

century: competitive since the first bank to establish a branch

in the suddenly emerging local distribution centres was likely to gain

a monopoly on trade in the immediate region, and speculative due

to the difficulty in determining which of the numerous instant towns

being created by railroad expansion were likely to survive as viable

communities. The dilemma for banks was one of erecting inexpensive

structures in a minimum amount of time which nonetheless reflected an

air of stability and security to potential investors. A building system

such as that marketed by B. C. Mills offered an obvious solution.

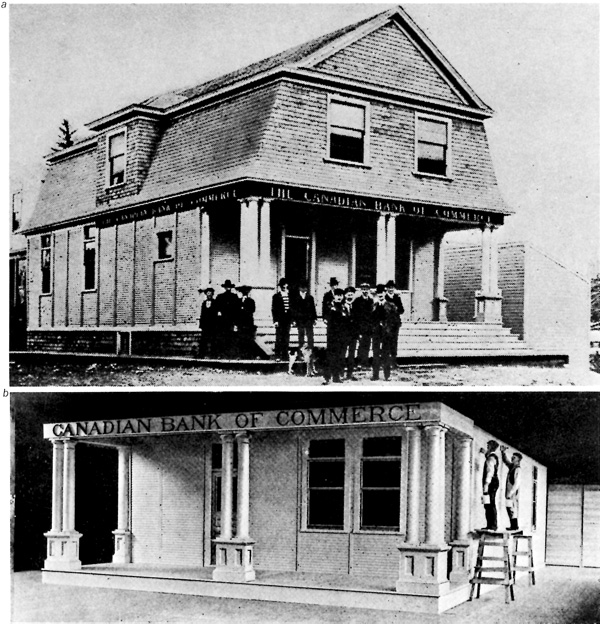

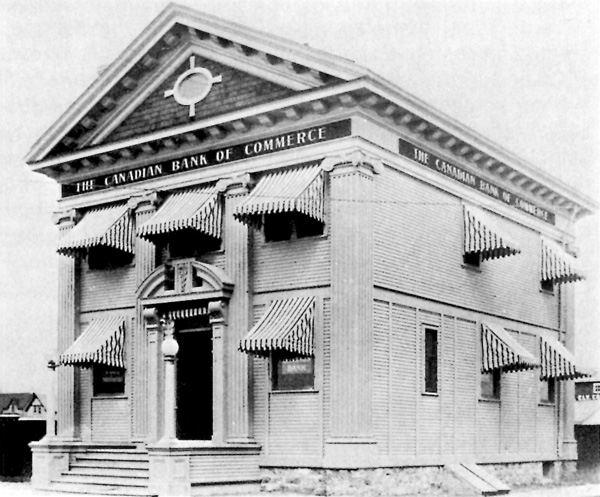

14 a, The first prefab bank commissioned by

the Canadian Bank of Commerce was this gambrel roofed structure, erected

initially at Latchford, Ontario, but subsequently moved to Cobalt,

Ontario, in November 1905. The building currently serves as the township

office. (V. Ross, The History of the

Canadian Bank of Commerce, Oxford Univ. Press, Toronto,

1922.) b, The walls of the same

bank in place in the Royal City Planing Mills erecting shed, receiving

the primary coat of paint. (B.C.

Mills, Catalogue of Patented Ready-made Houses [Vancouver,

1905].)

|

Two firms. the Bank of Montreal and the Winnipeg-based Northern Bank,

purchased a number of standard Townhouse Series prefabs as branch

buildings and managers accommodations in towns in British

Columbia.6 It was the Canadian Bank of Commerce, however,

that most fully exploited the potential of the prefabs and made them

enduring features of the western Canadian landscape. The bank initially

experimented with a slightly modified gambrel-roofed Townhouse design

for a branch in Cobalt, Ontario, erected in August 1905. It evidently

satisfied its owners, who recalled the circumstances of its erection 17

years later.

Tar-papered shacks and log cabins sprang up all over the town like

mushrooms during the night, and by January 1 there were possibly two

hundred shacks. In the meantime a few nice buildings were being

erected. In our case we imported a ready-made building from Vancouver, which

proved to be, and still is, the most attractive in the

town.7

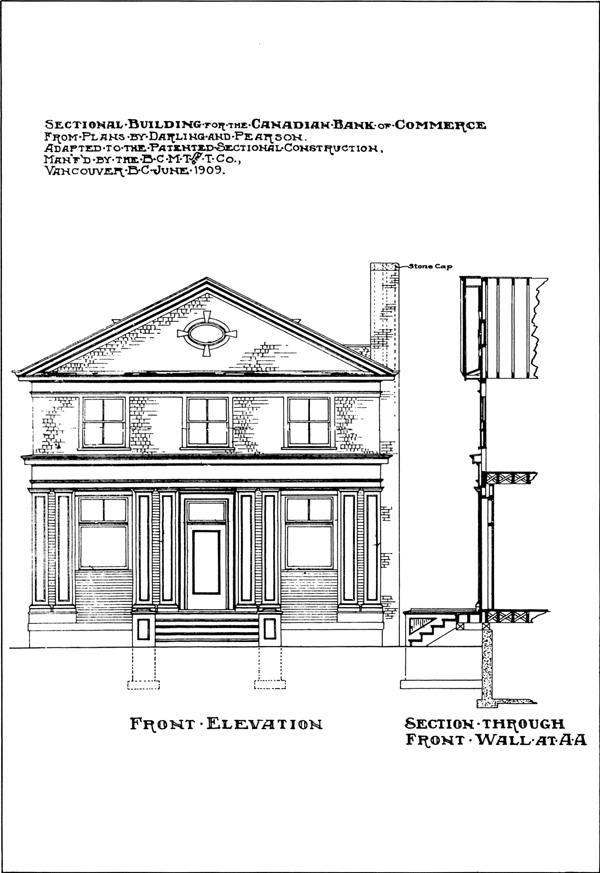

15 Front elevation and section, from original building plans. Bank

of Commerce, Bay and Douglas streets, Victoria, B.C. Darling and

Pearson, leading Toronto architectural firm commissioned by the

Canadian Bank of Commerce, designed this series of three bank styles

[see Figs. 16, 17, 18], adapting the B.C. Mills sectional

building system.

(Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.)

|

The Bank of Commerce, however had clearly defined policies regarding

the image it wished to project to the banking public vis-à-vis its

buildings.

The buildings erected by the bank are not the product of passing

fashion. While modern in spirit and diverse in every legitimate

respect, they are founded both in general design and in detail on those

classical traditions which never fail to command

respect.8

In major urban centres this carefully nurtured image had been

achieved through impressive neoclassical stone buildings. Branches in

suburbs and in smaller communities were scaled-down versions usually in

brick, of these structures. With the B. C. Mills prefabricated system,

the bank perceived a means of translating this image yet again into

small wooden structures which nevertheless could be cheaply and rapidly

erected in small western communities. Darling and Pearson, perhaps the

leading architectural firm in Canada and the architects responsible for

the design of many of the bank's major stone buildings as well as many

other major institutional buildings of the period, were now commissioned

to produce classical designs based on the prefab system.9 The

result was a series of three designs ranging from a small hipped-roof

model with a multi-columned front verandah to a massive looking

two-storey structure with neoclassical features including a handsome

pedimented entrance and fluted pilasters. Banking facilities, including

the vault and manager's office, were located on the first floor. The

second storey contained dormitory rooms to house junior clerks. These

rooms were occasionally converted into a suite for the manager in areas

where the housing shortage was particularly acute. In some cases, a

Townhouse design prefab was erected in the vicinity of the branch to

serve this purpose. The two larger models featured fireplaces on both

floors, located in the manager's office and upper dormitory lounge.

16 Prefabricated bank in Creston, B.C., featuring pilastered first

floor; built 30 July 1907.

(Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.)

|

These three models, termed by the bank as their "Prairie Type"

branches, proved to be an ideal solution to the various problems

confronting the firm during its period of western expansion. The bank's

policy was to keep several of these structures in reserve at the B.C.

Mills headquarters in Vancouver, from which they could be shipped on

short notice to meet sudden demands for branches as expanding railroad

lines opened new regions to settlement. Components for a single

structure could be packed in two boxcars for shipping.

The most spectacular demonstration of their usefulness occurred in

1906 when two hipped-roof models were shipped to San Francisco to serve

as temporary quarters for the firm's offices demolished by the

earthquake. One was subsequently employed as a sub-branch in that

city.10

17 Prefabricated bank in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, featuring

multi-columned verandah; built 14 May 1906.

(Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.)

|

18 Prefabricated bank in Humboldt, Saskatchewan, featuring two-storey

pilastered and pedimented façade; built 2 March 1906.

(Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.)

|

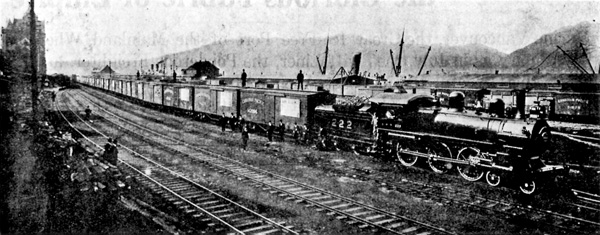

19 A trainload of banks leaving Vancouver, 1906, taken from a

full-page advertisement of the B.C. Mills range of products in the

B.C. Review during the peak phase of the bank's western

expansion.

(Vancouver Public Library.)

|

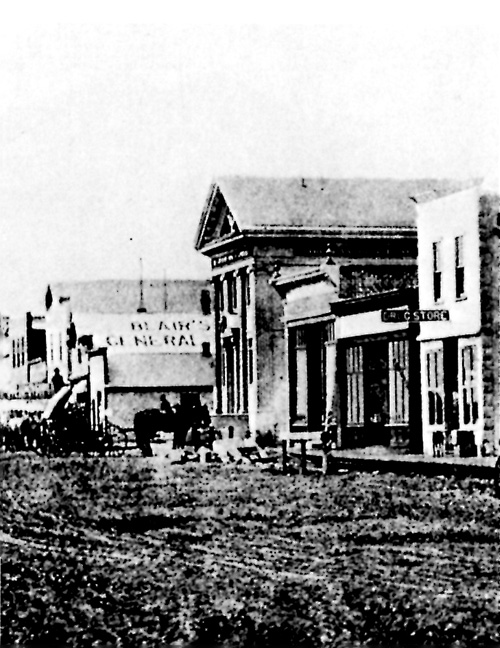

20 Bank built in Graham (originally Leavings), Alberta, on 21

February 1906.

(Glenbow-Alberta Institute.)

|

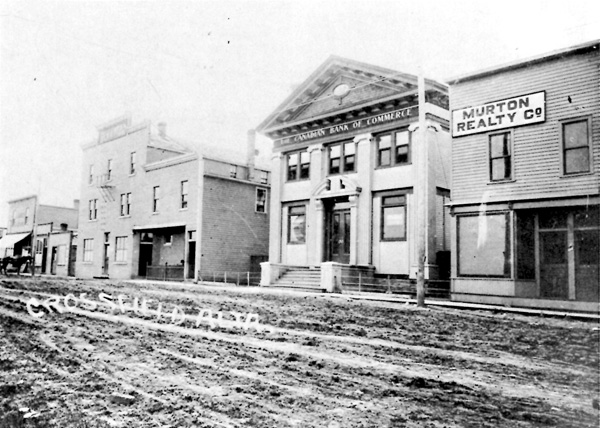

21 Crossfield, Alberta, 1914; typical streetscape featuring

prefabricated Bank of Commerce, built 17 April 1906.

(Glenbow-Alberta Institute.)

|

Although precise figures are not available, it can be safely

estimated that close to 70 prefabricated "Prairie Type" branches

were erected in western Canada between 1906 and 1910.11 During

this period a pattern emerged whereby new bank branches appeared in

newly established towns within months of railway construction. A notable

example is the Canadian Northern Railway line crossing central

Saskatchewan in 1905-06. A series of prefab banks was erected in seven

distribution centres — Kanask, Canora, Wadena, Watson, Humboldt,

Vonda and Radisson — within a few months of the line's

construction.12 Branches similarly appeared along Canadian

Pacific feeder lines throughout western Canada. Distribution ranged

from Winnipeg (excluding the Cobalt branch) west to Ladysmith and

Victoria on Vancouver Island. Because they were frequently the most

sophisticated structures in remote communities, they became

well-known and frequently cited landmarks.13 Although the

inhabitants of diminutive communities featuring a prefab bank were most

likely unaware of or indifferent to the fact, their town or village

shared the distinction, along with the major cities of eastern Canada,

of having edifices designed by Darling and Pearson gracing their main

streets!

Over a decade after the last prefab branches had been erected, the

bank remained satisfied with their performance,

No one can travel to any extent over the prairie provinces without

becoming familiar with the typical frame buildings erected by The

Canadian Bank of Commerce, such as those at Elbow, Canora, Humboldt and

Radville.... They have ... justified themselves, having proved durable

beyond all expectation, commodious, popular and creditable in

architectural effect. The pilastered and pedimented example illustrated

by Canora, and the broad and massive effect illustrated by Radville are

particularly satisfying in their effect, and dominate their surroundings

to the proper degree, without seeming out of harmony with

them.14

|