|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 21

by Philip Goldring The Origins of the Mounted Police ForceI "Come what may, there must be a military body, or, at all events, a body with military discipline, at Fort Garry; . . . the best force would be Mounted Riflemen, trained to act as cavalry but also instructed in the rifle exercise." So, in 1869, Sir John A. Macdonald expressed the idea which was the genesis of the Mounted Police. [1] It is likely that the Canadian government realized the necessity for a Dominion police in the Northwest from the moment it negotiated for possession of that territory, but the first reference to police in Macdonald's correspondence comes in mid-December 1869, very shortly after a body of Métis stopped Lieutenant Governor William McDougall at the American frontier and forbade him to pass. Immediately the prime minister wrote to the hapless governor, "Have you taken any steps yet to organize a Mounted Police? . . . You can . . . be organizing a plan for a semi-military body." The type of police which Macdonald outlined was a cross between the Royal Irish Constabulary and the native regiments of the British Army in India. The force was to have a mixed racial character: "pure whites & British & French Half-Breeds" were to be carefully mixed in the different troops of the force so that no one element would predominate. Macdonald clearly underestimated the depth of the chasm between the Métis and the Dominion, for he confidently anticipated that there would be no need to send a military force to the newly acquired territory. "The cost of sending a Military force will be so enormous, that . . . it would be a pecuniary gain to spend a considerable amount of money in averting the necessity by buying off the insurgents." [2] The Métis proved impossible to buy. Loyalty to their people and to their past ran too deep for them to throw in their lot with a strange new government. The intransigence of their resistance under Louis Riel and the resultant creation of Manitoba as a province induced the Dominion government to shelve plans for a locally recruited police. Tentative efforts to recruit a mounted police force in Ontario early in 1870 likewise came to naught, and the government put together a purely military expeditionary force. One imperial infantry battalion and two specially recruited militia battalions — the Ontario and Quebec Rifles — were dispatched to Red River in the summer of 1870. Their principal purpose was to restore and then to preserve order in the settled area of what became Manitoba, and it proved convenient to leave them there for some years as a buffer between rowdy elements of the old and the new populations of the province. [3] Yet it remained clear to Macdonald that a different sort of force must be raised as soon as circumstances north and west of Manitoba demanded an effective agency for enforcing the law. For the first several years, therefore, the militia served as a stopgap in Manitoba while the rest of the Northwest was without effective law enforcement. Macdonald never abandoned his idea for a mounted police force although he continued to defer it until it appeared more urgently necessary. Manitoba, as a province, was responsible for its own law enforcement and Macdonald envisaged the proposed mounted force primarily as a buffer between migratory Indians and settlers who had yet to arrive. Late in 1871, he wrote to Gilbert McMicken at Fort Garry, There must be a Mounted Police Force, say of 50 men, well selected and fully organized. Such a force could be sent at a moment's notice at any time on the Plains, when wanted. I look forward with some anxiety to a conflict between the Indians and the new settlers who will scatter over the Saskatchewan Valley next year. An infantry force will be of little value in preventing such encounters. [4] Political violence in Manitoba showed the continued need for a substantial militia force there and the anticipated rush of settlers proved an illusion; Macdonald continued to procrastinate in withdrawing the militia and organizing the police. [5] It was April 1873 before he took any positive steps toward creating the police force which he had first envisaged more than three years earlier.

Meanwhile, pressure mounted in the West in favour of the immediate organization of a police force. Lieutenant Governor Archibald sent out Captain William F. Butler to investigate conditions west of Manitoba. [6] Butler's colourful report emphasized the need for a mounted force though he suggested a military body, not police. His judgement was corroborated the following year by a report from Colonel P. Robertson-Ross, the adjutant general of Canada's militia and permanent force. Butler, Robertson-Ross and other observers were really only repeating a series of commonplace notions about the administration of the Northwest. These early recommendations differed from Macdonald's publicly expressed views in only two respects, first in assuming the use of military garrisons rather than police detachments, and second in believing that these detachments should be deployed instantly. Macdonald was skeptical of the military and felt that the militia at Fort Garry would be quite sufficient for the time being. When white settlers were actually living close to Indians in the territory, then friction might develop beyond the effective range of the Manitoba garrison. Macdonald's views were soon subjected to strong criticism from Alexander Morris, who had replaced Archibald as lieutenant governor at the end of 1872. Morris was often regarded as an alarmist, inclined to exaggerate all the problems of his realm and indifferent to the Dominion's need to balance strict economy against the supposed requirements of the territories. It is true that he viewed the future of Canada with unbounded optimism, yet he was inclined to paint each practical administrative problem in the gloomiest possible colours. By 1873, however, he was not far from the truth in believing that the future of the territories depended on swift and effective enforcement of the law. "The presence of a force," he wrote in January, "will prevent the possibility of such a frightful disaster as befell Minnesota & which without it, might be provoked at any moment." [7] At length, Macdonald was convinced that it would be well to prepare for a force beyond the borders of Manitoba and he began to draft legislation to cover the complex problems of administering the laws of the Northwest Territories. (These laws, framed by the territorial council at Fort Garry, were enacted by order in council in Ottawa.) Early in May Macdonald introduced in the House of Commons the Bill commonly referred to as the "Mounted Police Act." Although the bulk of this Bill concerned the Mounted Police, its full contents were enumerated in its title: "An Act Respecting the Administration of Justice, and for the Establishment of a Police Force in the North-West Territories." The two main sections of the Bill were closely related, since the senior officers of the police force were also to be stipendiary magistrates and as such would not only preserve order, but would also administer justice in accordance with the judicial provisions of the Act. The second part of the legislation outlined the structure, powers and duties of the force, and established basic qualifications for policemen. They were to be "of a sound constitution, able to ride, active and able-bodied, of good character, and between the ages of eight een and forty years." Recruits were to be literate in either French or English. The act authorized a force of up to 300 men, plus officers, but specified that the full strength need not be raised until the governor-in-council saw fit. Macdonald, introducing this legislation to the frugal Parliament, noted that he did not intend to appoint anywhere near the authorized number "at first or for a long time yet," and in reply to a question from the opposition, confirmed that after the creation of the police, the militia force at Fort Garry would be reduced "by degrees." The Act received royal assent on 23 May. [8] The passage of the Mounted Police Act wrought a sudden change in one part of the Department of Justice in Ottawa. Hitherto the Dominion Police Office had been a small, quiet branch of the department where the files were encumbered by nothing more than the regular reports of the commissioner and his two constables. Then a remarkable transformation took place. Early in April, when word leaked out among the government's friends that the force for the Northwest was soon to be organized, letters of application began to trickle in from across Ontario. When Macdonald introduced his Bill in the Commons, the trickle became a steady stream, and the deputy minister, Colonel Bernard, was assigned to handle the flow of applications. Retired soldiers, restless young militia officers and sons or acquaintances of Conservative stalwarts pressed their claims upon the prime minister. Most supplied letters of reference praising their moral, military or political virtues. (One Captain Crozier of Belleville applied offering good Conservative credentials; after the change of government in November 1873, he applied again, recommended by Liberals. He was appointed in time to join the training camp at Lower Fort Garry.) A disproportionate number of applicants sought staff or desk jobs, and a few considered themselves well-qualified to command the force. Among these was Captain Butler. "I am now about to proceed to England with the intention of joining the Expedition at present being organised against the Kingdom of Ashanta [sic]," he wrote, "but as that Expedition is expected to finish its labours before the close of Winter I will, if still fit for service, be ready to move on the Saskatchewan early in the Spring." Other, less colourful, applications for command came from a retired British captain living near Toronto and from an Ottawa resident who claimed to have commanded mounted police in India. [9] All these applications, together with others from tradesmen who sought contracts to equip the force, apparently received some consideration though most, no doubt, were acknowledged in the succinct form noted on the cover of one file: "Answer — making no promise JAMD." There were exceptions; as early as 28 May 1873 Colonel Bernard noted on one file, "Sir J. promised an app [ointmen]t." This was the application of Major Walsh of Prescott, who subsequently had a distinguished career in the force. [10] But for the most part, Macdonald was in no hurry to make promises, whether the applicant asked for command, for a commission, or simply for enlistment in the lower ranks. In fact, the Macdonald government had other, more pressing matters on its mind during the summer months of 1873. The planned Pacific Railroad and the fate of the ministry itself hung in the balance while inquiries proceeded into the government's alleged corruption in seeking funds for the 1872 election. Macdonald worried a great deal about some of the disclosures and, worrying, he drank. Even if he had been sober and able to give his full attention to the police, he had not yet found a commander for the force. He had earlier favoured Captain Cameron, a young imperial officer and a son-in-law of Charles Tupper: "As one can do a good natured thing for a friend without injuring the public service, we may as well embrace the opportunity." [11] But by 1873 Cameron was employed with the boundary commission and other candidates had presented themselves. Macdonald was anxious to enlist the services of Colonel J.C. McNeill, an imperial officer who had been in Canada in the early 1870s, but McNeill, like Butler, had joined the expedition to West Africa and was not available. [12] The people of Red River had their own opinions about the command of the force and a faction pressed for the appointment of a French officer. This group was represented, rather improbably, by two Scottish traders, A.G.B. Bannantyne and the aging Andrew McDermott. Their first choice was Louis de Plainval, a colourful and erratic young Frenchman who had come to the West with the expeditionary force of 1870 and had remained to command the small and ineffectual provincial police force. When he left the scene midway through 1873, Bannantyne and McDermott turned their endorsement to Major L.M. Voyer, formerly of the Quebec Rifles. [13] Their wishes were frustrated, however, by Macdonald's continuing determination to appoint, if possible, an imperial officer.

This determination to have a British officer in command was part of a fairly comprehensive idea of the force which Macdonald had formulated. Macdonald never spelled his idea out at any one time, but the outlines of it may be gleaned from a number of sources, notably the prime minister's remarks to Parliament when he introduced the Mounted Police Act, and his correspondence with the governor general and the lieutenant governor of the territories up to the end of September 1873. Macdonald's plan was to have a mounted force of 150 to 200 men (under the direction of the justice department, not the militia) in the Northwest by the summer of 1874. The men would be recruited in the four eastern provinces and would train in Ontario during the winter of 1873-74, and then would go west as soon as the Dawson Road was open. At the same time, part of the militia was to be withdrawn from Fort Garry. Eventually the police force would be raised to its full strength of 300 men and, when the need for a special force at Winnipeg had passed, the militia would be further reduced. [14] If such a program was to succeed, creation of the police force had to begin in the summer of 1873. Despite various setbacks, the timetable was met; organization was under way by the end of August. The obstacles were considerable as the government struggled under the burden of disclosures and accusations concerning the Pacific Scandal (or Pacific Slander, as stout defenders of Macdonald called it). Macdonald wasted much of the summer in a stupor and little was accomplished until the prime minister was prodded awake by the need to meet Parliament. Fortuitously this coincided with the arrival of a number of dark reports from the conscientious lieutenant governor of the Northwest Territories. Throughout the summer, Morris had expressed his displeasure at Macdonald's avowed intention of enlisting only 150 or 200 policemen, and painted a grim picture of affairs in the territories. He was particularly concerned about the southwestern corner where, he had just learned, American-based traders were plying a rich trade in whisky with the Indians. Morris was deeply apprehensive about the effects of this debilitation on tribes already weakened by the starvation which had been experienced in many camps the previous winter. He particularly feared the possibility of an outbreak of hostilities by the Blackfoot, a tribe which he estimated to contain perhaps as many as 10,000 warriors. These were living in dangerous proximity to the American traders, beyond the influence of the Canadian government or even of the Hudson's Bay Company although they were well within Canadian territory. Morris, insisting that he was not an alarmist, urged the government to avert the possibility of an Indian war which might at any time break out, either between traditionally hostile native tribes or against white settlement. [15] At last, in mid-August, Morris's sense of urgency provoked a serious discussion of northwestern affairs in the Dominion cabinet. Early in August the minister of the interior, Alexander Campbell, received a dispatch from Morris which Campbell misconstrued as a request to send troops immediately to the Blackfoot country. Campbell was infected with Morris's concern and asked the cabinet to sanction the dispatch of 150 soldiers from Manitoba to the whisky post of Fort Whoop-Up; he also proposed to recruit enough men to bring the Fort Garry detachment back up to full strength. [16] This idea received some consideration before the cabinet rejected it. Concentration of such a large number of troops in one small part of the territories would involve enormous expense without affording protection to most of the region. Nonetheless, Campbell's suggestion must have moved Macdonald to sit down and commit to paper his preparations for the organization of a mounted police. Parliament was prorogued on 13 August and Macdonald drafted an order in council authorizing the creation of a 300-man force. This was introduced in council on 27 August. [17] The whole question of the police force had never evoked much excitement outside the Northwest and the justice department itself, but the government's organ in the capital, the Ottawa Daily Citizen, trumpeted the birth of the force on 28 August, reporting the introduction of the order in council and declaring that the force was "to be organized immediately." [18]

Morris could take credit for the fact that his dispatches on the state of affairs in the territories had prompted the government to take immediate action. A delay of a few weeks longer might have seen the force lost in the flurry of activity surrounding the ministry's collapse on 3 November. There was little public reaction to the announcement of the formation of the force, beyond a brief rumour that the command would be offered to Captain Butler. [19] The government's decision passed with little public notice beyond a few terse lines in the Citizen, which found further justification for the government's policy in reporting a hideous incident which might have been prevented had the force been established a year earlier. This news concerned the Cypress Hills massacre, the killing of 20 or more Assiniboines on Canadian soil in a drunken clash between the Indians and a party of white traders and wolf-hunters from the United States. If the Republic cannot teach its subjects to respect law it is time that the Dominion should . . . Vigorous action on the part of our government in this direction may save us future trouble not only from the lawless citizens of the neighbouring country, but also from the North West Indians who will not be slow to defend themselves if the Dominion Government should appear to them incapable or unwilling to afford them protection. The organizing of the Mounted Police Force, which as we announced yesterday, will be commenced at once, may prevent a repetition of the disgraceful scene to which our despatch from Fort Garry refers. [20] Reports of the killings reached Ottawa too late to play any role in the decision to organize the force, but did have some bearing on the manner in which the police were recruited and trained. [21] The shape of the embryonic force was determined by the order in council of 30 August. The men would be divided into six troops or divisions designated by the letters "A" to "F." Each division was to be commanded by a superintendent and inspector, assisted by two officers with the rather confusing titles of superintendent and sub-inspector. A commissioner would command the entire force. The noncommissioned officers were to be one "chief constable to rank as Sergeant-Major" in each division and one constable for every ten ordinary sub-constables. The administrative structure of the force in the field was to be kept as simple as possible; one man was to serve as paymaster and quartermaster of the entire force, with only one constable in each division to assist him. No administrative structure in Ottawa was created at this time; the organization of the police was undertaken initially by Macdonald himself with the assistance of the militia staff and the two senior men in his department, Hewitt Bernard and Hugh Richardson. Afterwards, a full-time comptroller was appointed. Salaries for officers were reasonably generous, ranging from $1,000 a year for sub-inspectors to $2,000 for the commissioner. Constables would receive one dollar a day; sub-constables' pay was fixed at 75 cents. The latter salaries were not as meagre as they might sound, for the lower ranks were also to receive "rations, barrack or other lodging accommodation and Medical attendance free; and such clothing as may from time to time be fixed by Order in Council." The act authorized the appointment of a surgeon for the force, but Macdonald decided that since the police were to be "scattered in small parties over the North-West, one Surgeon at Head Quarters would be of comparatively little use to the Force as a whole." Instead, local medical men would be engaged as needed. In a circuitous way, the Cypress Hills incident affected one important part of Macdonald's plan — the training of the force in Ontario. At first Macdonald had taken the massacre in stride, appointing a special commissioner to inquire into the matter and extradite the offenders from the United States; [22] then he reverted to the important work of organizing the mounted police. The massacre stirred up even less public interest than the formation of the police, but it did offer Macdonald a chance to appeal in stronger terms for the services of an imperial officer. "This Indian massacre at Fort Benton [sic] shows the necessity of our losing no time in organizing the Mounted Police," he wrote to the governor general. Then he made his pitch: "May I ask you if you thought of writing to the Horse Guards to get the service of the Commissioner of Police recognized as Military Service? If this were accorded to us, our range of choice would be considerably enlarged." [23] But Macdonald was still obviously not as alarmed about the massacre as Morris, for he wrote in answer to the latter's plea that the police should be sent immediately, "Our present idea is to drill them all winter here, and send them up, with their horses as soon as the Dawson route is open in the Spring. Do not you think, on consideration, that that is by far the best plan?" [24] Morris most definitely did not think so and stepped up his attacks on the prime minister's more optimistic view of the situation. In every rumour, in every hindrance to his administration, Morris saw a threat of Indian warfare or of renewed Métis resistance; his gloomy reports became shrill and impassioned pleas for help, from either police or militia reinforcements. Finally, amid vague reports that the Métis were conspiring to prevent the signing of further treaties between the Canadian government and the Indians, Morris wired Macdonald, "What have you done as to Police force their absence may lead to grave disaster." [25] The prime minister capitulated. He ordered the police recruiters (already travelling across eastern and central Canada in search of men) to redouble their efforts and to report to Collingwood as soon as possible for transportation to the Northwest. [26] At the same time, he explained this sudden departure from previous policy to the governor general: Morris is getting very uneasy about matters in the North West. The massacre of the Indians by the Americans has greatly excited the red men there . . . . He is so pressing about the necessity of having the Mounted Police there, that although we intended to concentrate them at Toronto and Kingston for the winter and give them a thorough drilling before going west, we found it necessary that the force should be sent up before the close of navigation. It would not be well for us to take the responsibility of slighting Morris' repeated and urgent entreaties. If anything went wrong the blame would lie at our door. [27] This decision was to have major repercussions for the recruitment of the force.

The formation of the mounted police force took little more than two months after the passage of the order in council. It owed its rapid creation partly to the exertions of Bernard and Richardson in Macdonald's department, but mainly to the acting adjutant general, Colonel Powell, and the commanders of the military districts of eastern Canada and Manitoba. This is ironic, for Macdonald had been determined from the first to keep the police separate from the militia and within his own purview at the justice department, [28] yet he would have failed to meet his own deadlines had he not been able to lean heavily on the men, expertise and parliamentary grants of money at Powell's disposal. Even the backbone of the force — the bulk of its officers and some of the NCOs — came from the Canadian militia or the permanent force. After the decision to organize the force was announced publicly, the government was temporarily diverted by the need for rapid measures to pursue the perpetrators of the Cypress Hills massacre. This emergency was speedily dealt with by issuing special instructions to Gilbert McMicken, a former Fenian-hunter and commissioner of Dominion police, who had recently accepted a number of government appointments in Winnipeg. Once this matter was dealt with, Macdonald plunged back into the organization of the force. He contacted Powell on 8 September and informed him that the justice department would need considerable assistance from the militia in recruiting the new police force. On the following day, he approached Lord Dufferin with his request for assistance in getting a British officer as commissioner. [29] The justice department required a broad range of assistance from the militia. In effect, the individual deputy adjutants general were to put their resources at the disposal of the police recruiting officers, providing whatever information, funds or facilities were needed to enlist the men and transport them to Ontario. [30] The decision taken by Macdonald on 24 September to send the force as soon as possible to Manitoba put further strain on the recruiters and tightened their dependence on the militia. As Macdonald wrote to Lord Dufferin, "No time is to be lost. The Dawson route is not open after the middle of October." [31] The men in Macdonald's office knew little about the Dawson route, but the militia had been sending men to Manitoba that way since 1870. Powell therefore made the necessary arrangements with the manager of the Northern Railway, which operated trains from Toronto to Collingwood and steamers from there to Thunder Bay. He also gave instructions to Simon J. Dawson of the Department of Public Works, in charge of the route to Fort Garry from Prince Arthur's Landing on Thunder Bay. Powell ordered boots and caps for the mounted police. He told Richardson what supplies the police must procure for themselves and what they could expect to find along the route, and he selected a capable staff officer, Major D.A. McDonald, to proceed to Collingwood and there coordinate the arrival, equipment and dispatch of the contingents of police as they arrived. [32] The force's debt to the militia did not end there, for the government took the essential step of choosing a temporary commissioner at Fort Garry to prepare for the force's hasty and almost unexpected arrival. The obvious choice for this duty was Lieutenant Colonel W. Osborne Smith, the officer in charge of military district No. 10, Manitoba. Smith immediately set to work procuring horses, renting and fitting up barracks and contracting for supplies for the force. [33] By year's end, Smith had turned over command of the force in Manitoba to its new full-time commissioner, Colonel G.A. French, but in the brief flurry of organization, the militia had proved indispendable in the creation of the mounted police.

Preliminary recruiting orders had been given as early as 9 September to Captain Charles Young, [34] a retired imperial infantry officer who was to raise the Nova Scotia contingent, but active recruiting did not begin until ten days later. The records of recruitment are sketchy for Ontario, where James Morrow Walsh, James Farquharson Macleod and John Breden recruited about 80 men. (These three recruiters, together with the four in Quebec and the Maritimes, became the first officers of the force.) [35] In the eastern townships the recruiter was William Winder, a militia captain from Compton, while Ephrem A. Brisebois raised a contingent in the St. Lawrence valley, including Montreal. The recruiter for New Brunswick was Jacob Carvell of Saint John, a former officer in the Confederate army. Charles Young enlisted 20 men in Halifax. [36] There is little official record of how the original policemen were chosen. No recruitment posters have survived nor is it likely, in the haste in which the force was raised, that any were printed. Two officers asked for permission to advertise in the newspapers, but apparently did not do so. [37] Winder located part of his contingent through local members of Parliament, notably J.H. Pope, [38] but MPs do not seem to have been used extensively for recruiting. It seems likely that most of the new policemen were found through the militia. A few vacancies had recently been filled in the force at Fort Garry; the local district commanders must have had lists of late or superfluous applicants for the limited number of positions at Fort Garry. Now a second chance arose for young men to go west for three years' service and a promise of a land grant at the end of it, and it was doubtless through the militia that the police recruiters found many of their men. The recruiting in Quebec started about 24 September Ephrem Brisebois set up offices in the Hôtel du Canada and in the Casino de Montréal, the latter being the former headquarters of the Papal Zouaves. His efforts received some notice in the press although the remarks of a Protestant newspaper, the Daily Witness, reveal a total lack of planned advertising. The Witness first learned of the recruiting from the columns of its French-language contemporaries and acidly suggested that "there is no official attempt made to invite other nationalities but the French to enlist in this force." [39] After Brisebois had secured a number of men in Montreal, he moved to Quebec, where the Daily Mercury remarked on 1 October that "Sub-Inspector Brisebois has been in town recruiting for the force, and several young men of this city, Kamouraska, Saguenay and elsewhere have already enlisted." [40] As soon as he reached his quota of 20 men, Brisebois proceeded to Collingwood. There he joined with Winder (who had managed to find a dozen men in the eastern townships) and with several Ontario recruits, enough to make up a party of two officers and 62 men. Under Winder's command, the party sailed for Thunder Bay on 8 October aboard the Northern Railway Company's steamer Chicora. [41] Jacob Carvell managed to raise his quota and reach Collingwood well before the departure of the last steamer though his efforts were undermined by faulty instructions. He received his orders for the most part by word of mouth from Captain Young, who had also had only sketchy instructions and vague written orders from Richardson. Nonetheless, Carvell proceeded apace with the recruiting, starting at Saint John and working his way to Shediac by 30 September, and back to Saint John the following day. He must have had some presentiment of the difficulties which would later arise for he wired Ottawa for permission to exceed his quota: "I want permission to engage eight more men to prevent complications arising from making extraordinary effort to do this work quickly." [42] His foresight proved justified when, five weeks later, four of his men refused to take their oaths and had to be sent home from Manitoba. It is uncertain whether he received permission to over-enlist, but he did have 24 men with him when he left Saint John on 2 October for the long trip through Maine and Quebec to Collingwood. He reached that port on the seventh, well ahead of the other Maritime contingent under Charles Young. [43] Young left Ottawa for the Maritimes on 18 September, carrying his own and Carvell's instructions. He interviewed Carvell on 24 September and reached Halifax about the twenty-seventh. [44] There his methodical and orderly progress became a scramble when he received Richardson's telegram informing him of the government's change of plans. "Utmost dispatch requisite. First detachment goes Manitoba early next week." The public works department was already advertising that it would not accept passengers or freight for the Dawson route after 10 October, but Young still acted as though there were no need for haste. Finding himself short of money, he asked on 2 October for permission to take his men by steamer from Pictou to Montreal, arriving at Collingwood on the twelfth. Again Richardson prodded him, "You have not a moment to lose. Move at once by quickest route." [45] The rail connections between Nova Scotia and central Canada were little better than the steamboat schedules and it was 6 October before Young could start out. He had filled his quota on 1 October and had evidently had plenty of men to choose from for on one day he interviewed 50 men and rejected all but ten. The local opposition press was indignant to see young men, "some of the best mechanics in the city . . . who can earn from $9 to $12 per week here" setting out for the "uncertainty" of the Northwest. Nonetheless 20 men were found and on 1 October all gathered at the drill shed to take their enlistment oath from a local magistrate. On the sixth, a crowd of relatives and friends collected at the Intercolonial Railway depot to see them off. [46] Young accompanied his men, pausing at points along the way to report his progress and to plead with Richardson for more money. On the ninth he wired from Toronto, "Orders required as to route & only ten dollars left telegraph at once." [47] Fortunately Inspector Macleod reached Collingwood with his detachment and ample funds only hours after Young arrived there, and on the tenth they sailed. A relieved Major McDonald capped off a chaotic week of activity with this cheerful telegram to Hugh Richardson: The remainder of the Bobbies consisting of three officers and fifty-three men under command of Inspector Young sailed from here by the Frances Smith at ten o'clock last night immediately upon the arrival of the late train. [48] The Cumberland, the Chicora and the Frances Smith carried the mounted police from Collingwood to Prince Arthur's Landing on Thunder Bay. From Thunder Bay their route, the Dawson Road, climbed over rugged terrain, linking wagon roads to short stretches of navigable water, until it reached the Savanne Portage — the height of land between Lake Winnipeg and the Great Lakes — almost 900 feet above Lake Superior. From the Savanne, the route followed the course of Rainy Lake and Rainy River, across the Lake of the Woods and into Manitoba by a 100-mile road from Lake of the Woods to St. Boniface, opposite the tiny but boistrous provincial capital of Winnipeg. The Dawson Road was a variation on the old canoe route of the NorWesters who, until 50 years before, had brought to Canada the trade of the prairie regions and beyond. A similar route had also been used briefly by the abortive North-West Transportation and Navigation Company, which had tried for a few years after 1857 to reclaim Red River for the Canadian commercial empire. The Dawson Road was by no means superior to the system of American railways and navigable rivers which the Hudson's Bay Company had employed for much of its transport since 1859. (This latter route was taken by the second contingent of police in 1874.) The only advantage of the Dawson route was that it lay wholly in Canadian territory, linking Collingwood to Fort Garry as directly as possible without trespassing on the territory of the neighbouring republic. As such, it remained an important transport route for over a decade until abruptly superseded by the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The police left Collingwood in high spirits, relieved that they had left behind the worst of the confusion, if not the worst of the travelling. Recruits aboard the Chicora enjoyed the diversion provided by the constant singing and dancing of their French-Canadian comrades; mild pranks (including depredations on the officers' special rations) amused some of the men. They were not yet acquainted with military discipline. [49] The Grand Trunk Railway had lost part of Brisebois's baggage and seasickness swept through Young's detachment. On the whole, however, the head of Lake Superior was reached without serious incident. The first detachment reached Thunder Bay on 8 October and set off immediately for Fort Garry. Progress was hindered by high winds and a few early snowfalls; it was also interrupted at one point by hostility between the police and some of the government officials along the route. This lack of cooperation was apparently sparked by the domineering conduct and articulate profanity of Major Walsh. Despite adverse weather and frayed tempers, the police reached Fort Garry on the twenty-first. [50] The third detachment was less fortunate; it encountered harsher weather and the steamboat schedule was quite inadequate beyond the height of land dividing the Hudson Bay and Great Lakes watersheds. Equipment became soaked and soon froze, and men whose boots had frozen were forced to wrap their feet in rags and march through mud which, in the words of one recruit, James Fullerton, "was frozen enough to let you through and the ice cut your legs." Eventually their ordeal was over, as they were met by dog sleds a few miles west of Lake of the Woods, and they reached Fort Garry on 31 October. The first detachment had gone to the Lower Fort by steamer, but a few days of sub-zero temperature had frozen the river solid, so the last police went down by sleigh. [51] They arrived at their new barracks exhausted and footsore but exhilarated by the novelty of their voyage. The last of them were barracked by the first of November and they settled down for the winter in Canada's tiny outpost, the province of Manitoba. The first of their trials was over.

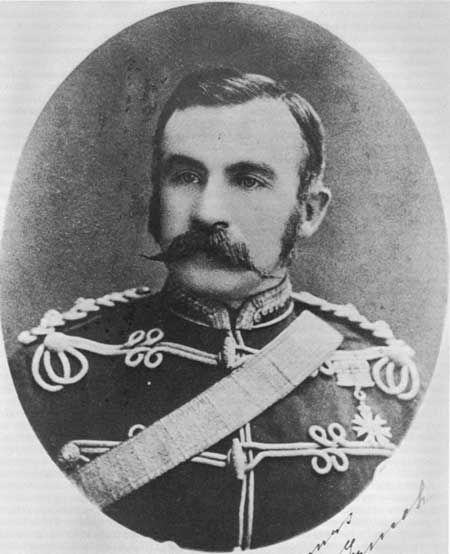

Happily for the recruits, a hardworking and competent officer had been preparing for their arrival. As soon as Macdonald decided to send half the force west in the autumn instead of waiting till spring, he appointed W. Osborne Smith commissioner. Smith, a veteran of the Crimean War and the Fenian Raids, commanded the troops at Fort Garry. [52] He would later have a serious quarrel with the Mounted Police over a trivial but distasteful incident, but from his appointment at the end of September until George French arrived to take up his command in mid-December, the exertions of Osborne Smith were vital to the early formation of the Mounted Police force. Smith's first concern was to purchase suitable mounts for the police. "No time should be lost in getting these so as to have them in thorough training for any movement in the spring. Canadian horses do not do well till after a year's acclimatization. Horses can be bought much lower now than in the spring." He succeeded in purchasing 33 horses before the three divisions arrived and while this was far short of the number eventually required, it provided enough mounts for training. The description of the first horses of the North-West Mounted Police is worth noting; One hundred and Twenty Five dollars to be the price, the Horses to be over Four and under Seven years . . . . To be Fourteen hands three inches high at least . . . . A proportion of mares will not be objected to. When stallions are brought for inspection and approved they will be accepted as they stand, or it required by me altered at your risk. [53] Shortly after Smith was appointed, he received assistance in the form of the new quartermaster and paymaster of the force, the first of the Mounted Police to reach Manitoba. The justice department, after sifting through the applications of several retired army quartermasters, had selected Edmund Dalrymple Clark, a young nephew of Sir John A. Macdonald. Clark proved to be a precocious and immature officer, much preoccupied with politics, personal advancement and the uncertain state of his romantic affairs in Ottawa. [54] His double job was too much for him and after 13 November Jacob Carvell took over as acting quartermaster, leaving Clark the functions of paymaster only. [55]

Far more important than any other task facing Clark and Smith was the problem of finding suitable barracks for 150 men. The acting commissioner briefly considered the idea of scattering them among the immigrant sheds and Assiniboine Barracks in Winnipeg, and the militia buildings of Lower Fort Garry. [56] He quickly abandoned this idea and negotiated with the Hudson's Bay Company to quarter the whole force at the Stone Fort. The warden of the provincial penitentiary at the same place promised convict labour, if needed, to move supplies, and a small army of carpenters swarmed over the fort repairing and remodelling buildings. [57] Militia stores were sorted out to see what equipment could be spared for the police and arrangements were hastily concluded through the lieutenant governor to have stables erected near the fort to accommodate 50 horses, with harness rooms and storage for hay and oats. By the time the last detachment had arrived, Osborne Smith was able to report that "the barrack accommodation is nearly complete." [58] The acquisition of substantial parts of Lower Fort Garry had not been entirely effortless. The government owned several buildings there, but expensive alterations were required and the Hudson's Bay Company (which had already surrendered a major warehouse for the penitentiary) was most reluctant to rent out more than one of its remaining buildings. The Company also had to provide extra labour to cope with the force's demands for fuel and rations. On the whole, however, the Company did not suffer by the occupation, for in addition to $3,000 rent for three buildings, it must have made a profit on the large contract for supplies and on the canteen which it operated for the police (many of whom were reprimanded during the training period for too-generous patronage of the Company facility). [59] As much as possible, the Company hoped, the police activities would be carried out in buildings already owned by the government. These consisted of a small structure between the men's house and the bakery, and a large guardhouse beside the river gate. The small building was extensively modified by the addition of a kitchen and washroom, and served as an infirmary. The militia guardhouse could have barracked a considerable number of men, but it was preserved as a guardhouse. So all living space had to be rented from the Company. There was little dispute over the old wooden storehouse — the Northern Department warehouse of busier days — near the northeast bastion; likewise, there seems to have been no argument over officers' quarters. Smith found suitable rooms in the attic of the Big House though the more fastidious Lieutenant Colonel French was later to complain that "officers quarters are about as bad as they well could be . . . divided from each other by wooden partitions which do not reach the ceilings." Smith, having secured these buildings, cast covetous eyes on a new, two-storey wooden shop which had just been completed for the Company's retail trade operations. This, he suggested, would make ideal barracks. Chief Factor John H. Mactavish replied testily that the store was essential to the Company's operations, but Smith took it anyway and told Mactavish to make the best deal he could with the government in Ottawa. The Company later tried to claim $3,000 rent for this one building, but eventually settled for $1,000, the same sum the police paid for each of the other buildings. The new store subsequently provided most comfortable accommodations for the recruits of "B" Division, while the remaining two divisions were barracked in the three-storey warehouse across the courtyard. [60] The Company's men at both forts were kept busy throughout the winter of 1873-74 supplying the Mounted Police. There were small matters to be taken care of, such as detailing two men every Tuesday to carry cordwood, [61] but the major part of the contract covered foodstuffs, all the necessities of life for man and beast: fresh beef and mutton, flour and bread, salt, pepper and potatoes for the men; hay, straw, oats and bran for the horses. The contract also included coal oil, "of the best quality pure, and clear, and warranted to burn without causing an offensive smell." [62] Although the original requisitions have not survived, Dalrymple Clark's monthly records show that the force spent just over $3,000 per month for food, light, fuel and forage. This was in addition to rent and private purchases made by individual members of the force.

During the space of three months, the justice and militia departments had collaborated to create the raw materials for the long-a waited force to patrol the Northwest. The driving forces behind this activity had been Macdonald, whose ideas formed the basis for the organization, and Morris, whose insistence during the long summer of 1873 had ensured that Macdonald would not default on his own previous plans. The force was conceived as a protection for white settlers on the plains; it was created to protect the Indian from the whisky trader and the government from both; it was sent west, eight vital months ahead of schedule, to pacify the lieutenant governor's fears for the security of Canadian government and settlement in the Northwest. But the Mounted Police force of 1873 was far from the Scarlet Force of legend; it lacked the training, the discipline, even the uniform which became famous. It was a group of young men, far from home, appointed to an enormous task which they were not yet prepared to execute. |

|||||||||

|

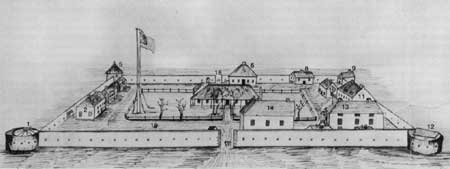

||||||||