|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 2

An Archaeological Study of Clay Pipes from the King's Bastion, Fortress

of Louisbourg

by Iain C. Walker

Part I The King's Bastion and its Casemates: The Pipes and Their Dating

Because the time span of the casemate under study is relatively short

(about 50 years) dating of pipes has been done primarily on the

evidence of makers' marks and names. With the exception of the Dutch

bowls, all bowls from which the shape could be deduced appeared to be

basically of Oswald's type 9 (Oswald 1961: 60, 61). This type of bowl

seems to have been the result of the influence of a Dutch pipe type

— brought over by the troops of William III at the time of

the English Revolution in 1668 — on the traditional barrel-shaped

English pipe bowl.1 Oswald dates this type to about

1680-1730, noting that in England it occurs in the West Country (that is,

the Bristol area) and in London and the Home Counties. In the New World

at least, the export version (Oswald's type 9c) and numerous variants

and derivatives were universal long after this, and certainly as late as

about 1780 (I. Noêl Hume 1963: 262). In England, Oswald's type 10

continued the more traditional features in various forms. This type

continued for most of the 18th century until type 11, a derivative of

type 9, became standard and finally set the norm for what is

traditionally considered the shape of a British clay pipe. In the New

World, however, as indicated above, the type 9 shape was universal

— perhaps because Bristol, where such pipes are datable to before

1700, was such an important export centre — and there seem in fact

to have been definite "export only" models.

Harrington's method of dating pipe fragments by bore diameter

measurement (Harrington 1954) was not used in this study, as the

relevant Harrington period, 1710-50, covered virtually the entire

occupancy of the area involved. Binford's straight-line regression

formula based on Harrington's work (Maxwell and Binford 1961: 107-9;

Binford 1962: 19-21), however, was applied to the various layers in

order to obtain comparative evidence.

The order of layers in this casemate from top to bottom runs from

Layer 1 to Layer 12, inclusive.

|

| Layer 2 |

|

| 29.1: |

Spur and bowl fragment, with B on left side of spur, raised; right side

of spur illegible. |

|

| 29.7: |

Bowl fragment, heel and stem fragment,  raised on base of heel, the arms of

the city of Gouda raised on a projection on either side of heel and

surmounted by a raised S, the mouth of the bowl having a milled edge

(Fig. 5, a-c).

raised on base of heel, the arms of

the city of Gouda raised on a projection on either side of heel and

surmounted by a raised S, the mouth of the bowl having a milled edge

(Fig. 5, a-c). |

|

| 32.5: |

Bowl fragment, vague design resembling a heart in a circle of

irregularly shaped dots on right side of bowl, all raised (Fig.

6). |

|

| 32.6: |

Bowl fragment and part of stem, part of a design the same as

above, extremely vague. |

|

| 48.1: |

Bowl fragment and heel, R on left side of heel,

B or R on right; large, spidery letters. |

|

| 48.2: |

Bowl fragment, mermaid in oval

impressed on base (Fig. 7, left). |

|

| 55.1: |

Stem fragment and part of heel, foot of letter probably T on left of

heel, D on right. |

|

| 55.3: |

Bowl fragment and heel, probably crowned F on left side of heel, crowned

S on right. |

|

| 55.4: |

Stem fragment with the letters DUNIER-

(the letters U and I are uncertain) followed

by an indecipherable letter or letters with

two vertical strokes, raised from a depressed

border; below the word a toothed

edge and above, possibly, a straight line. |

|

| 60.1: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, crowned 6 raised from a depressed

surround in two concentric ovals on base of bowl; coat of arms of city

of Gouda similarly beside it to left; the mouth of the bowl has a milled

edge. |

|

No significant pipe material came from Layer 1. In Layer 2 the following

material was studied (the catalogue number given is the lot number followed by

the object no.).

The standard work on the pipemakers of Gouda (Helbers and Goedewaagen

1942) does not list a crowned 6, but it is illustrated along with of

her marks all captioned merely as 18th century (Pl. VIII). The coat of

arms of the city of Gouda was put on certain Gouda pipes only after

1739-40 (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942: 18, 48), however, so this pipe

cannot be earlier than this date. That the crowned 6 was in use prior to

1739 is suggested by its occurrence on a pipe without the coat of arms

from Santa Rosa Pensacola, Florida, a Spanish settlement founded in

1722 (Omwake 1964: 23-4). (There is confusion as to the meaning of the

coat of arms. Gouda pipes came in three qualities known as porceleyne,

fijne, and slegte — porcelain [actually a high polish],

fine, and ordinary — and in November, 1739, according to Helbers

and Goedewaagen at one point [p. 18] to prevent merchants mixing pipes

permission was given to differentiate the porcelain class by adding the

Gouda arms to the bowl, However, sales of fine pipes dropped so much

because buyers thought they were ordinary pipes that on 4 March 1740

permission was given to mark fine and ordinary pipes with the arms,

surmounted by the letter S [slegte], on both sides of the bowl.

Elsewhere, however [p. 48], it is stated that in 1739 fine pipes were to

have the single arms and that the 1740 authorization allowed the double

arms and letter S for ordinary pipes, porcelain pipes presumably being

left unmarked.) As Omwake notes only one other example of a pipe with

the single coat of arms known to him in North America this example and

that from Intrusion 1 can be considered very rare. (Two more pipes of

this class were discovered at Fort Gaspereau, New Brunswick [1750-56],

by the writer in 1966.)

The letters  are not listed by Helbers

and Goedewaagen, but the same illustration that shows the crowned 6

illustrates this symbol. Again the arms of Gouda indicate a post-1740

date. While the maker of this pipe cannot be identified, a V in the

middle of a three letter mark could stand for the "van" in a surname

— for example, Barend van Berkel had the mark are not listed by Helbers

and Goedewaagen, but the same illustration that shows the crowned 6

illustrates this symbol. Again the arms of Gouda indicate a post-1740

date. While the maker of this pipe cannot be identified, a V in the

middle of a three letter mark could stand for the "van" in a surname

— for example, Barend van Berkel had the mark  (Helbers and

Goedewaagen 1942; Pl. VIII and 127) — and there is recorded in

Gouda a family of van Ommen. Several generations of this family

were pipemakers, and at least one, Frans, was working at the time of

Louisbourg (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942: 188, 225). The only mark known

to have been used by the van Ommen family at this time, however, was the

crowned 79, and in fact it was extremely rare for a Dutch maker to use

his initials as a mark. (Helbers and

Goedewaagen 1942; Pl. VIII and 127) — and there is recorded in

Gouda a family of van Ommen. Several generations of this family

were pipemakers, and at least one, Frans, was working at the time of

Louisbourg (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942: 188, 225). The only mark known

to have been used by the van Ommen family at this time, however, was the

crowned 79, and in fact it was extremely rare for a Dutch maker to use

his initials as a mark.

The mermaid is a Gouda pipemaker's mark, but in this case the coat of

arms is missing. The design on the pipe shown here is the earlier of two

versions, on the original imprint of which it says, according to

Helbers and Goedewaagen (1942: 170, No. 78; cf. 207, No. 222), "13 May

1745," which would appear to imply that this was when it was registered.

However, another Gouda mark, the trumpeter, was first registered in

1674, and it is recorded (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942; 196) that its

original imprint bore an inscription dated 1769, so such inscriptions do

not necessarily indicate a terminus post quem. The absence of the coat

of arms from a pipe of as high quality as this example (and that in

Intrusion 1) might support the version of the meaning of the arms noted

above where the highest class of pipe, that called porcelain, did not

carry the arms; on the other hand the arms

may not have been added by all Gouda makers, the pipes may have been a

high-class imitation of Gouda pipes, or they might even have been made

prior to 1739. The first known owner of this mermaid mark was Jacob

Klaris, it was obtained on 31 July 1747 by Boudewijn Klaris and not

apparently sold again until 7 August 1770. It is quite likely that this

pipe and other examples to be noted at Louisbourg were manufactured by

one or both of the Klarises.

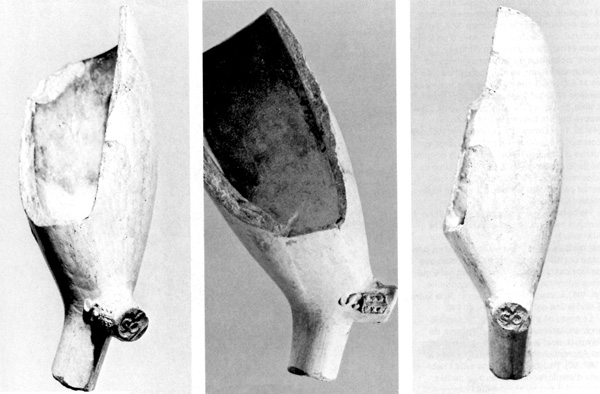

5 (a, left; b, center; c, right) Three

views of a Dutch pipe bowl. The letters S/V/O on the base of the heel

are the maker's mark, and the badge on either side of the heel is the

Gouda coat of arms surmounted by the letter S. This letter

(slegte: Dutch, ordinary), with the Gouda arms, was first

used in 1740, and indicates that this pipe belongs to the lower of the

three qualities of Gouda pipes, known in descending order, as

porcelain, fine, and ordinary, (The best-quality pipes

were not, in fact, of porcelain, but of polished clay.) (See p. 62.)

Context: 1755-60.

|

The history of the letters TD associated with clay pipes has already

been dealt with in some detail by the writer (Walker 1966a),

though more study of these pipes is still required. It is virtually

certain that the example here had on the front of its bowl (that is, the

side facing the smoker) the letters TD with a decorative motif above and

below, inside a thin rouletted circle, all impressed, similar to other

pipes described below. Pipes with a similar design are common from

camps of the period of the American Revolution (Calver 1931: 92, 93);

from Fort Ligonier, Pennsylvania, occupied between 1758 and 1765 (J. L.

Grimm, personal communication); from Fort St. Joseph, Michigan, which

was maintained by the French until about 1760; from an Indian

village site in Louisiana occupied intermittently until 1758 (both

quoted by Omwake 1965: 18-9, from an ambiguous reference in Quimby 1942:

545-6), and at Fort Michilimackinac where Omwake (1962; 1-2) tentatively

suggested a date of about 1755-65 for types that were possibly the

earlier of two main variants found there. They also occurred at Fort

Ticonderoga, New York (Gifford 1940: 128, 122, Fig. 13), founded in 1755,

and nearby Fort William Henry, 1755-57 (Omwake 1962: 9), but in unknown

contexts. On present evidence, therefore, TD pipes found at Louisbourg

are unlikely to date to earlier than the mid-1750s.

6 English bowl with design on its right side of an object resembling a

heart inside a circle of irregularly shaped dots. Context: 1755-60.

|

The most likely maker of these pipes appears to be Thomas Dormer, known

from two addresses in London in the 1760s (Oswald 1960: 68). The date on

which he received his freedom (became a licensed pipemaker) cannot be

later than 1763, the earlier of the two dates mentioned, but nothing

more is known of him, and no pipes of the type under discussion here are

in the collection of the Guildhall Museum, London (letters from A. H.

Hall, 18 March 1965 and R. Merrifield, 26 April 1965). Since he was

already working in the 1760s, however, he could have been working as

early as the 1750s.

The letters FS are not recorded by Oswald (1960: 91) before 1832:

however, from Casemate 3 Right a bowl with heel (4L.39, no object

number) was recorded and this had the letter F, crowned, on the left

side of the heel (the right side was broken off), and the letters FS

with the same decorative motifs and circle as that on the pipes bearing

the letters TD described above. Pipes with these letters, crowned, in

the same positions as in the example described above, on type 9 bowls

but with no design on the bowl, came from the Bankside excavations,

London (letter from R. Merrifield, Guildhall Museum, dated 26

April 1965). The use of crowns, though a typically Dutch form of marking,

is common in association with initials on either side of the heel on

pipes found in London covering the period from about 1690 to 1760

(Atkinson 1965: 254; 253, Fig. 6; 255, Fig. 7). The letters FS are not recorded at

Gouda, though a Frans Soet, who used the Gouda arms as his mark, gained

his freedom on 1 March 1737 (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942: 170, No.

157), but the style of these pipes is certainly English and the letters

must represent some unknown maker.

There are too many makers with the initials RB or RR (14 of the former

between 1706 and 1766 and six of the latter between

1713 and 1774-90) to make further identification feasible (Oswald 1960;

60-1, 90). No name resembling "Dunier-" is recorded either in England or

Gouda, but the name and style of marking suggest it to be Dutch

or French rather than English (cf. Duhamel du Monceau 1771: 24-5, Pl.

IX, Figs. 20-1, Pls. I-IV passim).

Virtually the only example of dating evidence derived from bowl shape

alone comes from 32.7 (Fig. 8, right), an entire bowl and stem fragment.

The relatively upright position of the bowl indicates that it is at least

typologically late, verging towards Oswald's type 11 which he dates to

1780-1850. An example very similar to but smaller than the one under

discussion came from Casemate 4 Right (4M.27.1) and was regarded by

Omwake (1965: 26) as being late, possibly intrusive, in terms of the

probable occupancy of these casemates. He dated the specimen to 1750-60,

but the present writer would not be prepared to preclude the

possibility of a slightly later date.

7 Two Dutch bowls with mermaid mark impressed on base of bowl. Contest:

both 1755-60.

|

|

| Layer 3 |

|

| 17.3: |

Entire bowl and heel, with crowned W on left side of heel, crowned M (?) on right, all raised. |

|

| 17.4: |

Heel and stem fragment, with crowned F on left side of heel, crowned S on right, all raised. |

|

| 17.5: |

Stem fragment with letters  and a line above, impressed, large shallow letters, widely spaced. and a line above, impressed, large shallow letters, widely spaced. |

|

| 35.1: |

Bowl fragment bearing part of encircled and decorated TD facing smoker, as described previously. |

|

| 54.1: |

Bowl fragment with heel, a crowned 14 raised from a depressed surround on the

foot of the heel and the arms of Gouda raised on a projection surmounted

by a raised letter S on either side of the heel. |

|

| 59.1; |

Heel and stem fragment, possibly a T on left side of heel, D on right, in small raised letters. |

|

8 Two English bowls of typologically late (in terms of Louisbourg) date

— possibly 1760s and later. Context: both 1755-60.

|

Helbers and Goedewaagen (1942: 213) do not list owners of the crowned 14

before the 19th century, but their illustration of a portable board

carrying 18th-century marks shows this mark, though uncrowned (Pl.

VIII). The use of the coat of arms and the letter S point to a date

later than 1740.

The pipe stem marked  appears to have been made by John Stephens

of Newport, who is mentioned in the Apprenticeship Rolls for 1751

(Oswald 1960: 92), although usually Stephens used much smaller, sharply

impressed letters set closely together, as will be illustrated later.

However, as six of Stephens' pipes with the latter form of lettering

came from Casemates 13-15 Right, where the terminal date for occupation

is about 1732, Stephens must have been working for at least 20 years

before his only recorded date; thus the fragment here does not

necessarily indicate a late date. It may, in fact, be an imitation of a

genuine Stephens pipe. However, from an unknown part of the fortress, a

pipe was found with the standard Stephens mark on its stem but with a

bowl on which were floral decorations. Such a bowl would not usually be

dated much before 1800, so there may have been a father and son of the

same name, at present unrecorded. (Since this was written D. R. Atkinson

[information via A. Oswald, November 1968] notes that a pipe made by

John Stephens is in Southhampton Museum and must be that of a local

[Southampton-Portsmouth-Isle of Wight] maker of the first half of the

18th century. This would agree with the Newport mentioned, a Newport

being on the Isle of Wight.) appears to have been made by John Stephens

of Newport, who is mentioned in the Apprenticeship Rolls for 1751

(Oswald 1960: 92), although usually Stephens used much smaller, sharply

impressed letters set closely together, as will be illustrated later.

However, as six of Stephens' pipes with the latter form of lettering

came from Casemates 13-15 Right, where the terminal date for occupation

is about 1732, Stephens must have been working for at least 20 years

before his only recorded date; thus the fragment here does not

necessarily indicate a late date. It may, in fact, be an imitation of a

genuine Stephens pipe. However, from an unknown part of the fortress, a

pipe was found with the standard Stephens mark on its stem but with a

bowl on which were floral decorations. Such a bowl would not usually be

dated much before 1800, so there may have been a father and son of the

same name, at present unrecorded. (Since this was written D. R. Atkinson

[information via A. Oswald, November 1968] notes that a pipe made by

John Stephens is in Southhampton Museum and must be that of a local

[Southampton-Portsmouth-Isle of Wight] maker of the first half of the

18th century. This would agree with the Newport mentioned, a Newport

being on the Isle of Wight.)

Oswald (1960; 84) lists seven pipemakers with the initials WM between

1698 and 1775. One of these, William "Morley" of Liverpool, noted in

1767, was in fact William Morgan who gained his freedom in that year

(Omwake, personal communication, 1965), and the William "Morley" noted

by Oswald in Liverpool in 1803 was William Morgan (junior) who gained

his freedom in 1803. A. Noêl Hume (1963: 23) noted that pipes bearing

these initials in various forms — on the base of heelless pipes and

on either side of the heel, plain or surmounted by crowns or sunbursts

— are common in Williamsburg, Virginia, in deposits usually datable

to 1750-65, though they had also been found in a deposit that appeared

from a Binford calculation to date to about 1740. A. Noêl Hume suggested

William Meakin of Chester who became a freeman in 1747. Until Liverpool

eclipsed it towards the end of the 18th century, Chester was a major

pipemaking centre; thus Meakin certainly seems a more likely maker than

the only other known maker with these initials between 1700 and 1747,

William Mellor of Bolsover, Derbyshire, apprenticed in 1723. Mellor

probably catered to a very local demand in a country area.

9 Stem fragment with letters OHST/INZ and a line above, impressed;

perhaps an imitation of the mark of John Stephens of Newport, England,

fl. 1751 (cf. Fig, 15). Context: 1755-60.

|

10 English bowl with lion guardant holding a halberd with a

semi-circular line round and below, surmounted by a crown with G on its

left and R on its right, facing the smoker, all impressed. Context:

1755-60.

|

Atkinson (1965; 253, Fig. 6; 254; 255, Fig. 7; 256) notes that among

pipes found in London, the initials WM, with and without the crowns,

occur on either side of the heel of pipes datable typologically from

about 1690 into the second half of the century; but Oswald lists no

known London makers with these initials during this period.

One fragment with these

letters crowned, one on either side of the heel (4F.6.19), came from Casemate 14 Right,

apparently in a 1720-32 context, but was perhaps intrusive from the fill

above. From Casemate 3 Right, a bowl and heel (4L.1.7) had the letters

WM, crowned, on either side of the heel; and these letters with the same

decorative motifs and rouletted circle as those described on bowls with

the letters TD and FS facing the smoker. From Casemate 5 Right

(4N.16.4) a bowl with identical decoration to one to be described (Fig.

10) had on either side of its heel the letters W

and M, each crowned. The example in Figure 10 has lost its heel. The

letters WM are not listed by Helbers and Goedewaagen but are

illustrated, crowned, on an 18th-century portable board of pipe marks

(Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942, Pl. VIII). Helbers subsequently noted

(quoted by Omwake 1965, letter: 5-6) that this mark, uncrowned, was in

use in Gouda in 1726; that it was subsequently crowned, and that it

lasted in that form until 1809. The pipes in question here, however, are

certainly English.

11 Two stem fragments with identical decoration of

a spiral of leaves. grape bunches, and rouletted

lines. Context: both 1755-60.

|

The use of the decorative motifs above and below the letters TD, FS, and

WM and their surrounding with a rouletted circle occurs with the letters WG

also; and pipes bearing these last letters, like those with the letters

TD, are known from camps dating to the American Revolution (Calver

1931: 2, 93). Pipes bearing the letters WM and FS in this style should

therefore be broadly contemporaneous in date, and thus late in terms of

Louisbourg's history. There must be some connection among these four

distinctive marks, but what this is has still to be determined (Cf.

Walker 1966a).

Proof of the widespread popularity of the TD and TD-derived marks comes

from excavations of the factory in Drammen, Norway,

about 25 miles southwest of Oslo belonging to Jacob Boy, a pipemaker who

was in business from 1751 to 1770. In common with other Scandinavian

pipemakers he manufactured pipes in both English and Dutch styles, and

one of the former was a bowl of the same shape as the TD-marked pipes

described above, with the letters IB facing the smoker but otherwise

identically marked, and the letters I and B on either side of the heel

(Pettersen and Alavik 1944: 53, illus. on p. 49).

|

| Layer 4 |

|

| 7.1: |

Entire bowl and heel, crowned W on left side of heel, crowned M on right. |

|

7.

(no object number): |

Mouthpiece fragment with a post cocturam coating of red wax. |

|

| 22.2: |

Bowl fragment, heel and part of stem, T on

left side of heel, either ID or two half-superimposed Ds on right, in large raised

letters as described above; part of an encircled and decorated TD on bowl facing smoker. |

|

| 22.3: |

Bowl fragment with figure 8 impressed on base parallel to line of stem. |

|

| 22.15: |

Heel with bowl and stem fragments, T on left side of heel, D on right in

large raised letters. |

|

| 37.1: |

Stem fragment, elaborately decorated with a spiral of leaves, grape

bunches, and rouletted lines. |

|

| 39.1: |

Stem fragment with identical decoration to above. |

|

| 41.1: |

Bowl fragment with heel, T on left side of heel, D on right in small raised letters. |

|

| 66.1: |

Complete bowl, lion guardant with semi-circular line around and below, surmounted

by a crown with G on its left and R on its right, facing the smoker, all impressed: the

beginning of a presumed heel is visible and on this is possibly part of an indecipherable mark (Fig. 10). |

|

| 66.2: |

Bowl fragment, heel and stem fragment, H

on left of heel, T on right. |

|

| 75.2 and 3: |

Stem fragments with identical decoration to 37.1 and 39.1 (Fig. 11). |

|

Material from Layer 4 is less readily datable than in Layers 3 and 2:

the pieces with the letters TD point to a date approximately the same

as these layers, but the heavily decorated stems are fairly closely

paralleled on the one hand from a rubbish pit in Chester which contained

material datable to the first three decades of the 18th century (Webster

and Barton 19S7; 20, 24), and on the other to material from the military

site at Penetanguishene, Ontario, occupied between 1826 and 1856, which

Omwake (1965, letter: 6-7; the material has not been seen by this

writer) notes as being typical of the 19th century. Spence (1942: 53,

51, Pl. IV, 1) suggests that an identically decorated stem to that

illustrated by Webster and Barton was made by Randle Meakin (brother of

William referred to previously), who became a freeman in 1721, or by his

son of the same name who became a freeman in 1784. Randle (senior) was

apparently working at least as late as 1758 (Spence 1942; 64). In view

of the known tendency of 18th-century Chester manufacturers to make

pipes with elaborate stem decoration, it is reasonable to ascribe these

three fragments to these makers. Although from the 17th century

onwards, Dutch pipemakers produced pipes with decorated stems, frequently

very heavily done in baroque ornament, the present writer knows of no

Dutch parallels to the decoration discussed here. A stem fragment with

the same decoration came from Casemate 3 Right (4C.39.93),

unfortunately from unrecorded digging there in the summer of 1962.

The bowl bearing the lion guardant and crown is the one already

mentioned as being identical to one with a heel bearing the letters W

and M, crowned, from Casemate 5 Right (4N.16.4). (Similar bowls are

known from London and one from Port Royal, Jamaica [Oswald, personal

communication], but none was in a datable context, and that from Port

Royal is certainly later than 1692 when much of that port was destroyed

by an earthquake.) The bowl is certainly English and the letters GR

presumably stand for Georgivs Rex, one of the three Georges, kings

of Great Britain from 1714 throughout the rest of the century. It seems

likely that pipes with this design were manufactured for a specific

occasion, and thus may be very closely datable it the event can be

determined. Unfortunately, the example from Casemate 5 Right came from

an area excavated by machine and its context cannot now be known.

As already noted, letters surmounted by crowns, including the letters

WM, occur from early in the 18th century, but it we take the Williamsburg

evidence that they occur normally about 1750-65 there, the obvious event

to be recorded by this design would be the accession of George III in

1760. An alternative but less likely explanation could be that the

design was produced as a patriotic gesture to mark the end of the War of

Spanish Succession in 1748. It the maker was indeed William Meakin, then

the pipe cannot be earlier than 1747, but it the occurrence of the

letters W and M, some with crowns, and in a context datable to about

1740 at Williamsburg is substantiated, then Meakin cannot be responsible

for these examples at least, and the patriotic gesture could have been

made during the troubled times in Britain of the Jacobite rebellion of

1745-46. The bowl shape is well-developed, and while the plane of the

rim of the bowl is not parallel with the line of the stem, this feature

is known on TD bowls from Fort Michilimackinac, which Omwake tentatively

dates to about 1755-65 (Omwake 1962: 1-2; cf. Duhamel du Monceau 1771:

4, Fig. 19). It should be dated later than 1727, when George I succeeded

his father.

12 Dutch bowl with the crowned 6 mark. Single coat of arms of the city

of Gouda indicates this pipe belongs to the upper classes of Gouda pipes

(cf. Fig. 5). See p. 62. Context: 1755-60.

|

The initials HT belong to three known 18th-century English pipemakers

(Oswald 1960: 96); Henry Turner who worked in London between 1707 and

1732, Henry Tucker of London who died in 1741, and Henry Tapplin of

Easworth, Hertfordshire, who is mentioned in 1750. From this it appears

that pipes bearing these initials were being manufactured all through

the period of occupation of Louisbourg.

The use of the figure 8 cannot be identified. The use of numbers was

another characteristic of the Dutch, but neither the style of number

nor the form or quality of the fragment show any Dutch influence. Had

this fragment and others like it described later come from unsealed

layers, it could have been suggested that they belonged to 19th-century

pipes, for by this time the use of numbers to denote styles and other

information on pipes was known (Omwake 1957a; 8; Walker 1966a:

88-9).

According to Fairholt (1859; 173) and Cassidy (1895: 18), the Dutch

were the first to wax the ends of their pipestems about 1700; and the

English quickly followed, using either wax (usually red) or a glaze

(Cooper 1907:108), a tin glaze which turned green on firing according to

Omwake (1965: 30). Omwake states that these methods appear to have been

used only on the best-quality pipes, for it is recorded (Cassidy 1895:

18) that the custom of dipping the stem in ale for a few minutes before

use was the practice for ordinary pipes. (The author knows of an

octogenarian in England who still [1968] does this with his clay pipes.)

According to Parsons (1964: 232, quoting two sources dated 1693), both

glazed pipes and glazed mouthpieces were common in the 17th century, but

the reference to glazed pipes seems certainly to refer to polished

pipes (Houghton 1727; 205; though published in 1727, this work first

appeared in 1693/94). Jewitt (1878 I: 298) extols glazed mouthpieces as one

of the merits of the pipes of an Edwin Southorn, working at Broseley in

the 1850s and 1860s, and implies that the custom was unusual. (It must

be admitted, however, that this particular account by Jewitt is

erroneous and contradictory in parts.) At Rosewell, Virginia, datable to

about 1772, a few mouthpiece fragments were found with coated or glazed

ends. One had a post cocturam red wax finish, as with the example here;

another had an ante cocturam black slip, and others had a treacly brown

glaze or a bluish green glaze flecked with light brown or orange (I.

Noêl Hume 1962: 221).

|

| Deposit containing Material from Layers 2, 3 and 4 (Intrusion 1) |

|

| 4.14: |

Stem and heel fragment, T on left side of heel, D on right in small

raised letters. |

|

| 4.15: |

Complete bowl and part of stem, a crowned 6 raised from

a depressed surround and enclosed in an oval on base of bowl, and arms

of city of Gouda similarly beside it to the left; the mouth of the bowl

has a milled edge (Fig. 12). |

|

| 4.16: |

Bowl fragment and part of stem, EC within a circle with a motif

resembling a modern trophy cup above letters and an illegible design,

perhaps a heart, below, all raised (Fig. 13). |

|

| 4.17: |

Heel and bowl fragment, with crowned W on left side of heel, crowned M

on right, all raised. |

|

| 4.18: |

Bowl and stem fragment with figure 8 impressed on base sideways to stem

(Fig. 14). |

|

| 4.19: |

Bowl and stem fragment with lower part of figure 8 impressed

on base transversely to stem. |

|

| 4.20: |

Stem fragment with  impressed on it (Fig. 15). impressed on it (Fig. 15). |

|

| 9.2: |

Complete bowl, heel and part of stem, T on left side of heel, D on right

in small raised letters, encircled and decorated TD facing smoker as

described previously (Fig. 16, right; Fig. 17, right). |

|

| 9.3: |

Complete bowl with heel broken off, decoration facing smoker as

described in 9.2 above. |

|

| 9.4: |

Bowl fragment, mermaid in oval impressed on base (Fig. 7, right). |

|

| 18.3: |

Bowl and stem fragment bearing part of a

decoration the same or similar to that already described in Layer 2, 32.5 and 32.6;

part of a circle of slightly raised dots is visible and something is raised inside this. |

|

18.

(no object number): |

Two bowl fragments with the same design as 18.3 above: in both the

heart-like object inside the circle is visible. |

|

The mermaid cipher of Gouda has already been discussed, and while it

may date only from 1745, it is not possible to be certain of this.

The pipestem marked  , like that mentioned earlier from Layer 4,

though the latter has a different style of letters, appears to have been

made by John Stephens of Newport, whose only known date is 1751. He must

have been in business for at least 20 years previously, however, on the

evidence from Casemates 13-15 Right, as six stem fragments with his name

have been found there, which dates them prior to 1732. , like that mentioned earlier from Layer 4,

though the latter has a different style of letters, appears to have been

made by John Stephens of Newport, whose only known date is 1751. He must

have been in business for at least 20 years previously, however, on the

evidence from Casemates 13-15 Right, as six stem fragments with his name

have been found there, which dates them prior to 1732.

Pipes found in Britain with initials on the side of the bowl are

restricted in distribution, though they are common in America (Oswald

1959: 59). Oswald does not list an encircled EC amongst those depictions

known, chiefly from the Bristol area in England (Oswald 1961: 56).

Elsewhere (1960: 63) Oswald lists only two known English pipe makers

with these initials: Evans Cheever of Canterbury who became a freeman in

1741, and Elisha Clanno of Exeter working about 1780. Either of these

pipemakers would agree with the late (in terms of Louisbourg) date

suggested by the previous evidence, though the latter must almost

certainly be too late. All the examples of these bowls from the casemate

have very indistinct marks, but the decorations above and below the

letters do appear to differ, or are even non-existent in certain

examples. The same can be said for the pipes with this mark from

Casemate 4 Right (Omwake 1965: 15-6). Proof of the varying nature of the

decoration comes from two well-preserved specimens, one from Casemate 5

Right (4N.7.22) where no decoration appears save for a colon between the

letters, and one from one of the basements of the Chateau St. Louis

(16D.4.9) showing a rather squat, solid crown above the letters and

below, a solid ace of clubs.

The crowned 6, a Gouda mark, as remarked previously, offers no

definite dating evidence other than its occurrence in Layer 2 and at the

contemporary site of Santa Rosa Pensacola (Omwake 1964). Similarly, the

figure 8 also offers no definite dating.

|

| Layer 5 |

|

| 36.1: |

Heel and stem fragment, crowned W on left

side of heel, crowned M on right. |

| 43.2: |

Bowl fragment, heel and part of stem, T on left side of heel, either D

or two half-superimposed D's on right in large raised letters,

encircled and decorated TD on bowl facing smoker identical to examples

previously described (Fig. 16, left; Fig. 17, left).

The occurrence of both these marks in

the previous layers suggests this particular

layer to be approximately contemporaneous with them. |

|

| Layer 6 |

|

|

No significant pipe material was recovered from this layer. |

|

| Layer 7 |

|

| 24.1: |

Heel and stem fragment, crowned F on left of heel, crowned S on right. |

|

| 83.1: |

Bowl, RT impressed on it facing the smoker,

inside a circle, all raised, on right side

of bowl (Fig. 18, bottom right; Fig. 19, right). inside a circle, all raised, on right side

of bowl (Fig. 18, bottom right; Fig. 19, right). |

|

The occurrence of the first mark in previous layers suggests this could

have been deposited approximately at the same time as the others;

however, the Tippet pipe may be appreciably earlier. There was a number

of Tippet pipemakers in Bristol in the latter part of the 17th century

and the earlier part of the 18th, and one branch of the family comprised

three generations all called Robert. Omwake (1958) and Oswald (1959)

have dealt with this branch of the family. The first-named appears to be

the more accurate account, and recently Omwake (1964: 20-3; and letter

dated 16 March 1965: 7-8) has supplied additional material.

The first Robert Tippet became a freeman in 1660 and died between 1661

(when he took an apprentice) and 1689 (when his wife is referred to as a

widow with an apprentice free that year). Presumably he was dead by

about 1682, for his widow apparently had her apprentice the full seven

years of legal apprenticeship, but Omwake's reasoning for 1680 is wrong

— his source has a comma omitted which wrongly implies the wife

had been a widow seven years in 1687. The second Robert became a freeman

in 1678 and was still alive in 1713. Meanwhile, his widowed mother

J(o)ane appears to have carried on her late husband's business, at

least until the turn of the century, for she is recorded in 1696. (There

are references in the records to both a Jane and a J(o)ane Tippet, whom

Oswald [1960: 96] lists as two different persons, but Omwake [1958: 5; 1964:

22] shows that they are in fact one and the same person.) The third

Robert became a freeman in 1713 and either he or his father is referred

to in 1720.2

It is extremely difficult to differentiate pipes made by various

members of this family, but the first Robert is unlikely to have been

making pipes of the type 9 shape, as he died just about the time these

pipes were beginning to appear. The rapidity with which this shape

gained in popularity, however, is indicated by the appearance of this

type with  in the medallion on the right side of the bowl, for

this almost certainly identified pipes made by J(o)ane Tippet and thus

can be dated, at the very latest, only to the earliest years of the 18th

century. One of these pipes found in this casemate is described later.

Omwake (1958: 12) tentatively suggested that the second Robert may have

started with the impressed RT on the back of the bowl, later adding the

medallion on the side, and that the third Robert may have used the

medallion without the RT, in which case all those at Louisbourg of

which enough evidence survives to make this assumption certain would

have been made by the second Robert. Gifford (1940: 128-9, 122, Fig. 14)

shows examples of Tippet pipes from Fort Ticonderoga distinctive in not

having the RT on the bowl. It any one of the Robert Tippets was still

working by 1755 when the fort was founded, then it would be the third,

thus agreeing with Omwake's suggestion. None of the material from Fort

Ticonderoga was excavated stratigraphically and it could be argued that

Robert Tippet pipes found there represent some prior settlement, either

Indian or European. These pipes are common on Onondaga and Oneida sites

dating from before 1700 to about 1750 (Hagerty, personal

communications). (Three were found, however, by the writer in the summer

of 1966 while excavating the closely dated site of Fort Gaspereau, New

Brunswick [1750-56]. indicating that the pipes, it not the maker, were

in existence as late as the 1750s. Further, two Tippet pipes were found

during excavation in 1969 of a wreck in Baie-des-Chaleurs, on the

Quebec-New Brunswick border, which was datable to 1760 [information from

R. Grenier, National Historic Sites Service].) in the medallion on the right side of the bowl, for

this almost certainly identified pipes made by J(o)ane Tippet and thus

can be dated, at the very latest, only to the earliest years of the 18th

century. One of these pipes found in this casemate is described later.

Omwake (1958: 12) tentatively suggested that the second Robert may have

started with the impressed RT on the back of the bowl, later adding the

medallion on the side, and that the third Robert may have used the

medallion without the RT, in which case all those at Louisbourg of

which enough evidence survives to make this assumption certain would

have been made by the second Robert. Gifford (1940: 128-9, 122, Fig. 14)

shows examples of Tippet pipes from Fort Ticonderoga distinctive in not

having the RT on the bowl. It any one of the Robert Tippets was still

working by 1755 when the fort was founded, then it would be the third,

thus agreeing with Omwake's suggestion. None of the material from Fort

Ticonderoga was excavated stratigraphically and it could be argued that

Robert Tippet pipes found there represent some prior settlement, either

Indian or European. These pipes are common on Onondaga and Oneida sites

dating from before 1700 to about 1750 (Hagerty, personal

communications). (Three were found, however, by the writer in the summer

of 1966 while excavating the closely dated site of Fort Gaspereau, New

Brunswick [1750-56]. indicating that the pipes, it not the maker, were

in existence as late as the 1750s. Further, two Tippet pipes were found

during excavation in 1969 of a wreck in Baie-des-Chaleurs, on the

Quebec-New Brunswick border, which was datable to 1760 [information from

R. Grenier, National Historic Sites Service].)

Oswald (1959; 61) notes that at one excavated kiln site in Bristol,

Tippet pipes of heeled, spurred, and heelless types were found, and at

another, heelless ones only, suggesting, in view of the finding in North

America of the last type only, that Tippet enterprises had a large

enough business to specialize in export only models. Even in today's

attenuated pipe industry, the firm of C.B. and McDougall of Glasgow

(Walker and Walker 1969), successors of D. McDougall Ltd. (founded in

1846, not as Fleming [1923: 243] states, 1810) had, until they closed in

November, 1967, between 30 and 40 moulds in operation to satisfy

different tastes in different parts of the world (Knight 1961: 34). The

occurrence of Oswald's type 9 pipes so exclusively in North America may

have been because of a similar predilection. Omwake (1958: 6) has

suggested that Tippet pipes found in England with the RT on the bowl

but not the medallion might be for the home market, and certainly all

New World Tippet pipes seem to have the medallion.

13 English pipe. EC within a circle with a motif resembling an antique

urn above letters and an illegible design, perhaps a heart, below; all

raised. Possibly the mark of Evans Cheever of Canterbury, fl. 1741.

Context: 1755-60.

|

|

| Layer 5/6/7 |

|

|

In some places, because of the thinness of Layers 5, 6 and 7, it was not

possible to differentiate them with certainty. The material described

here represents what was found in these areas. |

|

| 113.1: |

Heel, bowl and stem fragment, T on left

side of heel, D on right in small raised letters. |

|

| 115.1: |

Bowl fragment and portion of stem, fragment

of circle and bottom edge of letter raised on right side of bowl, perhaps EC

as below. |

|

| 115.2: |

Complete bowl and stem fragment, letters

EC with urn-like object above but apparently nothing below (cf. deposit containing

material from Intrusion 1; 4.16), encircled, all raised.

This mixture of layers contains nothing

previously unnoted in the way of dating material, and appears to be approximately

contemporaneous with the previous layers. If the letters EC belong to either known

pipemaker with these initials, a post-1741 date is indicated. |

|

| Layer 8 |

|

| 87.3: |

Stem fragment, crossed spurred pipes of

Dutch type and an apparent E on its back

above the bowls of the pipes, all impressed

(Fig. 20). |

|

| 106.1: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, EC with urn above and indecipherable

object below, all enclosed in a circle, all raised as described

previously. |

|

14 English pipe with figure 8 impressed on base at right angles to line

of stem. Context: 1755-60.

|

15 Stem fragment with OHN/TEP impressed; John Stephens of Newport,

England. fl. 1751. Context: 1755-60.

|

The piece with the letters EC is identical to other finds in previous

layers, suggesting the approximate contemporaneity of this deposit and

the other finds.

The crossed pipes, as mentioned above, are of Dutch shape, but the

standard both of the decoration and the stem itself seems to fall short

of the normal Dutch excellence. No definite identification can be found,

it was at first thought that the decoration represented a crude and

inaccurate version (perhaps forged) of the badge of the Gouda pipemakers

guild, which was two crossed pipes with their bowls up (unlike this

example where the bowls face out) surmounted by a crown (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942: Pl. I). Subsequently,

however, a stem fragment (16A.1.381) bearing the same design as this

stem, but with a more legible imprint, was recorded from the Chateau St.

Louis. The marks above the crossed pipes are now revealed to be a name;

the letters appear to read ALLT or ALLY, and above this again there are

marks tentatively deciphered as IOHN, though only the O is definite. No

pipemaker of a name resembling this is known either in England or The

Netherlands, and the name itself does not definitely indicate its

nationality. The pipes depicted on the stem, however, are certainly Dutch in shape.

From its form, one bowl from this layer, 13.3 (Fig. 8, left), might be

construed as being relatively late. The bowl is more upright than most

of those found in this area, and approximates one from Layer 2 (Fig. 8,

right), which was compared earlier with a larger but otherwise similar

bowl from Casemate 4 Right, for which a 1750-60 or later date was

suggested (Omwake 1965:26). This particular example (13.3) is larger

than the one from Layer 2 though not as large as the example from

Casemate 4 Right.

|

| Layer 9 |

|

| 73A.1: |

Bowl fragment and heel, of characteristic

Dutch shape and finish, with a crown surmounting what appears to be a claw

hammer on base of heel; the mouth of the bowl has a milled edge. |

|

| 73A.2: |

Complete bowl and heel, of characteristic

Dutch shape and finish, with a mark which

appears to be a hollow circle surmounted

by a barbell on base of heel; the mouth of

the bowl has a milled edge. |

|

| 73A.3: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, ER

impressed on bowl facing smoker (Fig. 21). |

|

| 73A.4: |

Complete bowl and heel, RT impressed on

bowl facing smoker, apparently an extremely faint shield-like badge with a cross

above on right side of bowl; underneath the

shield is what appears to be an asymmetric

inverted V, though this may be merely a

nonsignificant pattern, the whole raised and

enclosed in a raised circle (Fig. 18, top). |

|

| 73A.5: |

Stem fragment with complex decoration

comprising a transverse band of round dots

each surrounded by a circle, between

double parallel lines, followed by a panel

with barbell-like motifs parallel to each

other and lying parallel to the stem, followed

by a repetition of the barbell motif; the one

end of the decoration visible on this fragment

is edged with ogee impressions lying

parallel to the stem (Fig. 22). |

|

| 88.1: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, a

crowned 6 raised from a depressed surround in an oval on base of bowl; the mouth

of the bowl has a milled edge (Fig. 23). |

|

| 88.2: |

Very small fragment of bowl wall with part

of medallion and the letters HT inside (only

right half of the letter H present) separated

by a star, surmounted by a pyramid of six

very small diamond-shaped dots, enclosed

in a circle cog-toothed inside and out, all

raised (Fig. 24, right). |

|

| 94.1: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, RT impressed on bowl facing smoker

(Fig. 19, left). |

|

| 94.2: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment,  in

circle on right side of bowl, all raised

(Fig. 18, bottom centre). in

circle on right side of bowl, all raised

(Fig. 18, bottom centre). |

|

| 100.1: |

Stem fragment, with letters  impressed on it (Fig. 25).

impressed on it (Fig. 25). |

|

| 100.2: |

Bowl fragment and heel, W raised on left side of heel, other side

obliterated. |

|

| 100.3: |

Heel and stem fragment, crowned F on left side of heel, crowned S on

right, all raised. |

|

| 103.2: |

Stem fragment with half of a six-rayed star with circle in centre

surrounded by two concentric circles raised from a depressed background

(Fig. 24, left). |

|

| 109.7: |

Bowl fragment and heel fragment, EC very faintly marked with no

embellishments visible, encircled, all raised. |

|

| 121.1: |

Bowl fragment and heel, crowned B raised from a depressed surround on

base of heel. |

|

| 121.2: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment, base of RT

impressed on bowl facing smoker visible,  in circle on right of bowl, raised (Fig. 18, bottom left).

in circle on right of bowl, raised (Fig. 18, bottom left). |

|

| 121.3: |

Stem fragment, heel and bowl fragment,  raised from a round-cornered, depressed square on top of stem, the name

running at right angles to the stem (Fig. 26).

raised from a round-cornered, depressed square on top of stem, the name

running at right angles to the stem (Fig. 26). |

|

| 121.5: |

Bowl fragment and stem fragment with raised encircled cartouche of R.

Tippet on right side of bowl as above, but because of deposit of rust

only final T of surname visible. |

|

| 121.7: |

Heel and stem fragment, crowned 10 raised

from depressed surround on base of heel. |

|

| 131.1: |

Entire bowl of typical Dutch shape and finish, indecipherable mark on

left side of base; the mouth of the bowl has a milled edge. |

|

16 Two examples of English pipes with the letters TD; left, with

double D; right, single. Context: left, 1755; right,

1755-60.

|

17 Same two examples as in Figure 16, showing typical shape of English

bowl of this period; TB design on bowl and motifs below and above

letters and the rouletted enclosing circle.

|

Pipes made by the Tippet family have already been discussed and the

occurrence of five here suggests an earlier date than that deduced for

the previous layers. The absence from this layer of any pipes with the

letters TD, which are known to be late, and of which eleven were found

in the previous layers, reinforces this suggestion.

The Tippet pipe with the badge on the side was certainly not a

standard product of the family: indeed its occurrence seems completely

unrecorded to date. The heel suggests it may have been intended for the

English market. The pipe may have been intended to commemorate some

event, in which case it may ultimately be closely datable; but attempts

to identify it have so far failed. Pipes with the  as noted earlier, were in all probability made by J(o)ane Tippet, wife

of the first Robert Tippet, who apparently carried on her dead husband's

business after his death before 1682 until at least 1696. Pipes from a

site discussed by Omwake and Oswald also have the surname split in the

same place as this example despite coming from different moulds, and

other pipes illustrated by them use either

as noted earlier, were in all probability made by J(o)ane Tippet, wife

of the first Robert Tippet, who apparently carried on her dead husband's

business after his death before 1682 until at least 1696. Pipes from a

site discussed by Omwake and Oswald also have the surname split in the

same place as this example despite coming from different moulds, and

other pipes illustrated by them use either  (as examples 121.2) or (as examples 121.2) or  (as

in example 83.1). The (as

in example 83.1). The  pipe here is clearly identical to those

referred to by Omwake and Oswald; in fact, it these are made by the

widow of the first Robert Tippet the example in this layer is probably

the earliest pipe in the casemate, for it must date to the very

beginning of the 18th century at the latest. pipe here is clearly identical to those

referred to by Omwake and Oswald; in fact, it these are made by the

widow of the first Robert Tippet the example in this layer is probably

the earliest pipe in the casemate, for it must date to the very

beginning of the 18th century at the latest.

18 Four bowls manufactured by members of Tippet family of Bristol, all

with RT impressed on side of bowl facing smoker. Top, at present

apparently unique in North America, has heel and what appears to be a

badge in the medallion which normally takes the Tippet name. Bottom

left has R/TIP/ET inside medallion; bottom centre has IR/TIP/ET and

bottom right R/TI P/PET indicating the use of different moulds. Bottom

centre made by J(o)ane Tippet (see text). Remaining examples made by

second or third Robert Tippet, or both, who between them covered the

period from 1678 to after 1720. Context: top, bottom left, and centre:

ca. 1716-49/50; bottom right: 1749/50-55.

|

Nevertheless, the occurrence of two bowls marked EC, already noted in

upper layers and discussed earlier, would suggest a much later date for

the deposition of this layer if the identification of these initials is

correct; and the occurrence of a pipe with the letters FS, both crowned,

two other examples of which occurred in upper layers, suggests the same

conclusion.

The complexly decorated stem 73A.5 appears to be Dutch in origin, for

the decoration is paralleled on two stems with bowls attached from

Casemates 13 Right and 14 Right (4W.3.112, Fig. 38, and 4F.6.391, Fig

44, respectively), which have on the heel a crowned LV with what appears

to be a bird flying below. While this mark is not recorded by Helbers

and Goedewaagen, it is typically Dutch; and the bowl shape, while not

among the usual ones illustrated in Figure 27, may be a contemporary

of the type with the plane of its bowl parallel to its stem which,

brought to England in 1688, inspired the type 9 shape and its variants,

and ultimately was responsible for the shape that came to be associated

with all English clay pipes. Thus the shape itself, which appears not to

have caught on in The Netherlands, implies a relatively early date in

terms of Louisbourg; a supposition strengthened by its occurrence in

the right face casemates which were tilled about 1732.

The crowned 10 is also a Gouda mark, it is not listed by Helbers and

Goedewaagen, but one of their illustrations (Pl. VIII), captioned only

as 18th century, shows it.

The crowned 6, another Dutch mark, has already been referred to.

However, in this case, the coat of arms of Gouda is not present and it

seems probable, though not entirely certain, that this pipe dates to

before 1739-40.

19 One of the bowls shown in Figure 18 and another showing RT impressed.

|

The crowned B, also Dutch, was originally registered in 1661. The

earliest known owner, however, is a Bastiaan Overwesel who sold it on 6

November 1770 (Helbers and Goedewaagen 1942:139).

Oswald (1960: 63-6) lists a number of Carters, but only two, or

conceivably three, who could have been active during the occupation of

Louisbourg: James Carter of Rye, married in 1689; Richard Carter of

Bristol, freeman in 1706; and another James Carter, of Bristol, freeman

in 1734. The date makes it less likely that the James Carter of Rye

would have been the maker, and Rye was a tiny port in Sussex while the

port of Bristol was the centre of trade to the American colonies at this

time.

The style of mark on top of the stem is unusual, however, it seems

unknown in Bristol and there are unfortunately no pipes identifiable

with either Carter in the City Museum, Bristol (Lillico, personal

communication). On the other hand, the style is known in northeast

England, where it is the normal means of identification between about

1675 and 1725, though in a very much more ornate form (Parsons 1964:

245-7, Fig. 3a). Parsons does not list any makers by the name of Carter

from this area. (Since the above was written a C. Carter has been

identified, on the basis of excavated material, as probably a

Southampton pipemaker dating to about 1720-50. His pipes have a C on

either side of the heel and  on the stem [information from D. R.

Atkinson, via Oswald, November 1968].) on the stem [information from D. R.

Atkinson, via Oswald, November 1968].)

The initials ER are recorded for several pipemakers in the 18th

century, all occurring early: Edward Randall of London, making pipes in

1719; Edward Reed of Bristol, 1706-22; Edward Rushton of Liverpool,

1702-19; and another Edward Randall Jr., of Bristol, who became a

freeman in 1699 (Oswald 1960: 88-9) and who seems to be the same as the

London Randall noted above (Oswald 1960: 48).

Two pipes bearing these letters on the bowl facing the smoker, as

here, came from an Indian cemetery at Kutztown, Pennsylvania, and both

are of type 9c and similar in appearance to Tippet pipes (Pearce,

personal communication). The cemetery contained other material all

datable to the period 1700-40, and the child burial containing the

pipes in question also contained a silver spoon datable to 1720-25 with

crest and hallmarks from Philadelphia: Witthoft (in a letter) feels a

date in the 1720s for the burial is likely.

In view of the fact that these initials are similar in form to,

although larger than, the RT on the Robert Tippet pipes, there appeared

to be the possibility that the maker with the initials ER had been

apprenticed to one of the Tippet family, and that on becoming a freeman,

used his master's style. In this case the maker would most likely be a

Bristolian. Reed was apprenticed in 1699 to William Tippet senior,

perhaps a younger brother of the second Robert; though by a curious

coincidence Edward Reed's brother, Thomas, was apprenticed to the

second Robert Tippet in 1698 (Ralph, 1964, letter). Randall was

apprenticed to John and Mary Sindering in 1689, his father, a

pipemaker, being dead by this time (Ralph, 1965, letter). At Louisbourg,

in a context which cannot be closely dated, a pipe bowl (8A.3.1) was

found with the letters ER almost identical in style to the RT on Robert

Tippet bowls and with a medallion on the side enclosing an

indecipherable name (what appears to be the letter O at the end of the

middle line is all that is legible). It is tempting, and this thought is

not necessarily contradicted by Oswald's identification (1961: 62, n.6)

of a pipe with the letters ER facing the smoker and these letters on

either side of the heel as made by the Edward Randall of London

mentioned in 1719, to think that at least the pipe with the medallion

was made by an apprentice of one of the Robert Tippets. According to

Oswald (1960; 48), Edward Randall Jr., of Bristol was the same person as

the Edward Randall working in London 20 years later; if so, the use of

the initials on the bowl facing the smoker might have been inspired by

the Robert Tippet pipes, even if Randall had not been apprenticed to

that family. Were he later in London, Randall could have added the

letters to the heels of his pipes, following what seems to have been a

popular custom in the London area, as already noted (Atkinson 1965:

253-5).

20 Stem fragment with mark of two Dutch pipes, crossed, and what appears

to be the name SOHN(?)/ALLT or ALLY above. Name not decipherable on

this example but known from another fragment; all impressed, Context:

1749/50-55.

|

The initials HT have already been discussed when dealing with a pipe

fragment which has these letters on either side of its heel (Layer 4,

66.2). The right side of the bowl, as the smoker holds the pipe, was

missing in this example, and as makers' medallions are almost invariably

on that side, it is possible that the pipe from Layer 4 and the fragment

from this layer may have been made by the same person. However, as

three makers, who between them cover the period Louisbourg was occupied,

are known to have had these initials, no positive identification can be

given.

A pipe stem from the Chateau St. Louis (16F.2.7) reveals that the

name REUB/ENSI is in fact Reuben Sidney, but no maker of this name is at

present known either in England or Gouda. Presumably, however, he was

English. (Since this was written, Reuben Sidney has been identified as a

Southampton pipemaker who is known to have been active 1714-16

[information from Atkinson via Oswald, November 1968].) Helbers and

Goedewaagen do not illustrate any mark resembling a claw hammer, and

the uncertain mark resembling a hollow circle surmounted by a barbell

has no illustrated parallels, it is certainly not the milkmaid, which is

perhaps the nearest approach illustrated, nor is it the three-leaved

shamrock.

The encircled, six-rayed star on the stem cannot be identified at

present, though an unbroken specimen (16D.4.9) was found in the

chateau.

There is one bowl from this layer, 103.1 (Fig. 28), which approaches

the extremely elegant. elongated shape which is Oswald's type 9c

par excellence. As noted earlier, all the English pipes from this

casemate are basically of this type; indeed, they are universal in the

New World to the exclusion of the more common type used in England (type

10) during the greater part of the 18th century. At Louisbourg, however,

the slender long bowl set at a markedly obtuse angle to the stem as

shown here is unusual, this example being the only one known from this

casemate and one of the few seen in the Louisbourg material so far. As

noted earlier, A. Noêl Hume (1963: 262) shows that type 9 and its

variants last throughout most of the 18th century. This example most

nearly approaches a shape dated by Noêl Hume to 1720-80, and it was found

at Rosewell (A. Noêl Hume 1962; 220-1, 232, Fig. 35, 8) in a

context dating to the third quarter of the century. In itself,

therefore, this bowl does not add to the dating evidence of this layer.

It is interesting that this type of bowl is so rare at Louisbourg, as

it suggests that wherever the source of such bowls, it was not a place

that had much trade with Louisbourg, unless this particular type of

pipe failed to win favour in certain areas. As will be shown below, its

occurrence in this layer dates the pipe to not later than the 1740s.

Layer 10

No significant material came from this layer.

|