|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 18

A Campaign of Amateurs: The Siege of Louisbourg, 1745

by Raymond F Baker

Preliminaries

It was after sunrise on 11 May 1745 when the first colonial vessels

sailed across Gabarus Bay toward a small inlet known as Freshwater

Cove, about four miles southwest of Louisbourg, where the landing would

be made. From the ramparts of the fortress, French soldiers watched

anxiously as, one by one, the tiny transports assembled in the bay

between the cove and Flat Point.

Upon the fleet's appearance in the bay, the French rang bells and

fired cannon in Louisbourg to alert the garrison and the inhabitants of

the outlying settlements. Throughout the town, soldiers went to their

posts. Almost at once, the men took measures to secure the low wall at

the southeast part of the fortress, working hurriedly to erect a

platform of thick planks, upon which, before the day was out, they had

two 24-pounder cannon mounted and firing. At the same time, soldiers

mounted a number of swivel guns along the quay wall next to the

harbour.1

The New England militiamen on board the transports in the bay heard

the bells and the cannon and saw the defensive measures being taken

against them. But, undismayed, they prepared to scramble into the

landing boats as soon as the signal was given.

The Landing of 11 May

In the confusion and excitement of the moment, few of the New

Englanders who kept diaries or journals during the campaign remembered

the exact time the fleet came to anchor in Gabarus Bay. Some of them

believed it was 9 o'clock, while others thought it was not until 10

o'clock. Benjamin Cleaves, a clerk in Captain Benjamin Ives' company of

Hale's Fifth Massachusetts Regiment, wrote that the fleet "came in fair

sight of Cape Breton about 9 o'clock; Came to anchor about 10." The

official account of the expedition, prepared by Pepperrell and four of

his officers, places the time as between 9 and 10 o'clock. And Governor

Shirley (who received his information from Pepperrell) gives the same

time in a letter to the Duke of Newcastle in October

1745.2

The diarists were less uncertain about the place of anchorage. Most

of them agreed that it was about two miles below Flat Point or about

four miles southwest of the fortress. "Here we saw the light house &

ye steeples in the town," noted Benjamin Green, Pepperrell's secretary.

If these observations are reliable, the place of anchorage would have

been in the vicinity of Freshwater Cove, an inlet the French called

Anse de la Cormorandière. Because of the many vessels involved

(about 90), probably the whole area between the cove and Flat Point was

occupied by the transports.3

While the provincial army's presence off the coast in Gabarus Bay was

far from being a secret to the French, Governor Shirley seems initially

to have entertained some hope that Louisbourg could be taken by

surprise. Before the Massachusetts contingent sailed from Boston, he

gave Pepperrell a lengthy letter with detailed instructions on how the

campaign should best be conducted (see Appendix C). Many of these

instructions appear naive and impossible to execute. An early New

England historian, Dr. Jeremy Belknap, writing some 40 years after the

Louisbourg expedition, concluded that Pepperrell would have needed seven

years' experience as a general, the power of a Joshua, and men with the

eyes of owls to accomplish what Shirley suggested. And a noted British

naval historian, Admiral Herbert Richmond, called them "a perfect model

of the type of instructions to be avoided."4 But while

Shirley's tactical ideas were scarcely credible, his scheme did

anticipate the importance and relative vulnerability of two vital points

of attack: the Royal and Island batteries.

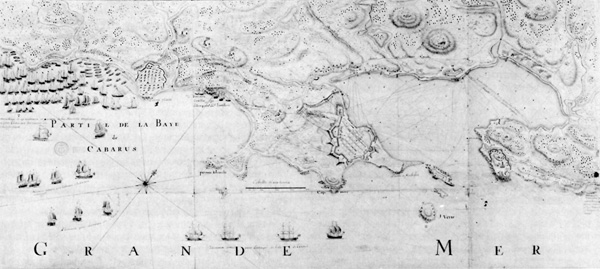

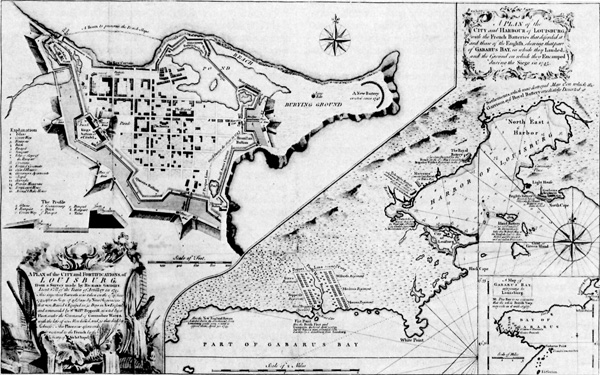

4 Fortifications of the town of Louisbourg in 1745, shown in a

plan signed by the French engineer Verrier.

(Archives Nationales, France.)

|

5 Louisbourg and the New England positions.

(Bibliothéque Nationale, France.)

|

Shirley contended that to surprise Louisbourg, the fleet's arrival

should be so timed that the landing could be made at night, "about nine

of the clock." The men were to be put ashore immediately and as quickly

as possible, all the while maintaining "a profound silence," lest they

awaken the unsuspecting Frenchmen. After the men had been properly

positioned around the fortress (all this to be done in the dark), at a

prearranged signal they were to storm the walls.5 Because of

the delay at Canso, however, and a contrary wind from Canso to

Louisbourg, the fleet did not arrive until after daylight on 11 May, and

whatever chance for surprise that might have existed had vanished.

The French probably would not have been taken completely by surprise

in any case. Louis Duchambon, who had been military governor at

Louisbourg a little over six months, reported that as early as 14 March

ships had been sighted cruising off the fortress.6 (The

intendant, François Bigot, confirms Duchambon's statement.)7

The number of these vessels steadily increased throughout March and

April and, though still in doubt as to whether the ships were French or

English (the ice in the harbour and bay keeping them at a distance), the

governor arranged for the safety of the inhabitants of the outlying

settlements should the ships prove to be English and a forewarning of

attack. He told the residents of the coastal villages near the town to

be ready to obey any signal he might give them. He also called together

all the residents of the town and harbour, divided the former, group

into four companies for defensive purposes, and instructed the latter

group to repair to the Royal Battery or the Island Battery upon a signal

from him.8

The anonymous habitant de Louisbourg asserted that for a

considerable time before the provincials appeared in Gabarus Bay, the

French were not unaware "qu'il se trâmoit une entreprise secrette

contre nous, à la Nouvelle Angleterre. Tous les jours nous recevions de

secrets avis qu'on armoit le long de la Côte." On 22 April, two men who

had come overland from Port Toulouse told Duchambon of hearing cannon

fire from Canso and that work was under way to restore the defences of

that place. A third man told of witnessing a battle between French and

English ships along the coast. By 8 May, Duchambon was certain that the

ships off Louisbourg were English, and two days later, in the dark and

fog of night, he despatched one of two ships prepared for the purpose

through the blockade to France to inform the government of the colony's

situation.9

Despite the apparent knowledge that "a secret enterprise" was in

preparation in New England, Duchambon seems to have made little effort

to meet the impending attack. He had tried to provide a large number of

fagots on the quay for the use of the fire ships; he had proposed a

battery on Cap Noir; and he had asked the ministry in France to send

more cannon, remarking that the cannon he did have were not "Suffisant

pour soutenir un Siege en form."10 His request for the

additional cannon had gone out in November 1744, much too late for the

ministry to send them in time, for it often took as long as a year for

such requests to be acted upon. So the French government had not

responded and none of Duchambon's proposals was carried out. Even had he

been able to take adequate defensive measures, it is unlikely that he

would have been able to effect them satisfactorily because of the

quality of the troops under his command.

Altogether, Duchambon's force amounted to some 1,500 men of the

Compagnies Franches de la Marine and militia, plus several companies of

the Swiss mercenary Regiment de Karrer. (The habitant stated that

this number could have been increased by 300 or 400 men who were at

Ingonish and vicinity, but that by the time Duchamdon decided to send

for them, communications with that place had been cut off.)11

The militia lacked training and the Compagnies Franches which

constituted about one-third of the total force, were inexperienced and

disgruntled over back pay and poor food and clothing. Duchambon had

inherited this discontented garrison from his predecessor, Duquesnel,

who had died in October 1744. Military discipline had been so poorly

maintained by Duquesnel, and Duchambon had so little succeeded in

controlling the disaffection, that in December 1744 the garrison

mutinied. Since then it had been in open rebellion against Duchambon's

authority.12 Only after the provincial army appeared in the

bay was he able to harangue them into obedience, with promises that all

would be forgiven if they settled down and did their duty. Even so, the

habitant later admitted, "nous n'avions pas sujet de compter

sur elles . . . . Des Troupes si peu disciplinées n'étoient guéres

capables de nous inspirer de la confiance . . . . je décidai qu'il étoit

naturel de s'en défier."13 It is hardly surprising that

Duchambon was so ill-prepared for the attack when it came.

The only measure Duchambon could offer when the provincial fleet

appeared on 11 May was to send a detachment of about 80 men to oppose

the landing. This force was made up of about 50 civilians (militia)

commanded by Port Captain Pierre Morpain and about 30 soldiers under

Mesillac Duchambon, the governor's son. (Another force of 40 men was

already somewhere in the woods around Gabarus Bay, where they had for

several days been watching vessels from Warren's fleet which anchored in

the bay from time to time.) One of the militia captains, Girard La

Croix, remarked that even this action by the governor was rather futile,

since the provincials were already ashore before Morpain and Duchambon

could arrive.14

In Gabarus Bay, the landing signal was given and the New England

troops scrambled into the landing boats. According to Pepperrell's

instructions from Shirley, the landing would take place in four

divisions, three of which were to go ashore at Flat Point and the fourth

at White Point farther up the coast. A council of war held at Canso on

16 April had, in effect, confirmed these instructions and the army was

divided into four sections. But the council decided against making the

landings at Flat and White points, choosing instead to send the army

ashore some three miles from the town and four miles from the Royal

Battery; in effect, between Flat Point and Freshwater Cove. As the army

prepared to disembark at this point, the French force sent out by

Duchambon appeared on the beach, "marching towards the place where it

was proposed to land our Troops."15

Seeing the enemy force approach, Pepperrell, instructed to keep any

resistance away from the main landing area as long as possible, sent

several boatloads of men to make a feint of landing at Flat Point Cove.

This "diverted the Enemy from proceeding further till they saw the Boats

put back and row up the Bay." In the meantime, the main landing had

started at Freshwater Cove. It was now almost 12 noon and a high surf

had developed, "which made it difficult landing," but pulling vigorously

against the breakers, a force of nearly 100 men managed to get ashore.

A few provincials disappeared into the woods in search of any concealed

enemy force, while the rest of the men advanced along the shore to meet

the French troops, who had discovered the deception and were now racing

for Freshwater Cove.16

After a brief but sharp skirmish, the French broke and ran for the

woods. "These Scoundellus french Dogs," wrote one New Englander, "they

Dare not Stay to fite."17 In the encounter, the French

suffered a loss of about six men killed, five wounded and one civilian

captured. Port Captain Morpain was also slightly wounded but managed to

return to the town. The captured civilian was Le Poupet de la

Boularderie, a retired officer of the Duke of Richelleu's regiment in

France. Several other Frenchmen were captured or killed in the woods

before they could regain the fortress. The provincials' loss was two or

three men slightly wounded.18

The French in Louisbourg, alarmed at the easy repulse of Morpain and

Duchambon, set fire to the houses and outbuildings beyond the Dauphin

Gate to deny their use to the enemy. The inhabitants with their personal

effects were brought into the town.19

Throughout the fighting on the beach, the provincial army continued

to come ashore along the coast between Flat Point and Freshwater

Cove.20 The high surf that continued throughout the day

increased the difficulties of landing, but by nightfall some 2,000 men

were ashore. Toward evening most of the transports moved up to the head

of the bay, where the riding was smoother and safer.21

On shore, the undisciplined volunteers succumbed to chaotic impulse,

and "Indeed! wee fill'd the Country," noted one enthusiastic soldier.

They had no specific orders as yet, but "Everyone Did what was Right in

his own Eyes Among which I was one." The men took to the hills, and soon

the French saw them ranging the heights in great numbers opposite the

King's and Dauphin bastions. The provincials were within cannon shot and

"at about two P.M. the cannon en barbette fired on several platoons

which seemed to be marching without formation toward the far side of the

bay." One of the New Englanders on the hills that day recorded (somewhat

matter-of-factly) that "one of the Balls wee took Up while it was a

roalling (wee Judg'd it to be A 24 Pounder)."22

The French saw still other men marching along the edge of the woods

toward the Royal Battery. This was probably a detachment of 400 men

under Colonel William Vaughan of Damariscotta, Maine, on its way to

plunder and burn the storehouses and the northeast harbour.23

The provincials on the surrounding hills so alarmed Duchambon that "Je

fis fermer Les portes, et Je fis pourvoir Sur Le champ a La Surette de

la Ville et placer environ 1100 hommes, qui se sont trouves pour La

deffendre."24 Even more alarmed was Chassin de Thierry,

commandant of the Royal Battery.

The Abandonment of the Royal Battery

The relationship between the appearance of the provincials on the

hills around Louisbourg on the afternoon of 11 May, and the abandonment

of the Royal Battery has never been clearly defined. Many historians

— those who bother to treat the subject at all — have

attributed the abandonment directly to the burning of the northeast

harbour storehouses on 12 May.25 The burning of the

storehouses might well have hurried the men who had returned to complete

the removal of the stores and ammunition, but the decision to abandon

the Royal Battery was made on the evening of 11 May.

In the late afternoon on 11 May (probably sometime after 4 o'clock),

Thierry wrote to Duchambon stressing the poor condition of the battery

and stating that he did not believe it could be held if attacked.

Thierry asked permission to withdraw the garrison, and he cautioned

Duchambon not to let the Royal Battery fall into enemy hands. He advised

that the cannon be spiked and the place blown up.26

Duchambon, upon receipt of Thierry's communication, hurriedly

assembled a council of war to decide what should be done about the Royal

Battery. Etienne Verrier, the chief engineer, was summoned. He reported

that the battery was indeed in a poor defensive condition: that some of

the epaulements of the left flank had been taken down the

previous year and had not been replaced; that the covered ways were not

fortified, and that without reinforcements the battery could not be held

against an attack of 3,000 or 4,000 men.27 On the strength of

Verrier's report, the council voted unanimously to abandon the battery

after spiking the cannon and removing all the stores and ammunition

possible. Such stores and ammunition as could not be salvaged were to be

dumped into the harbour. The council also wanted to have the battery

blown up, as Thierry had urged, but Verrier apparently objected so

strongly that the matter was dropped.28

Duchambon ordered Thierry to withdraw the garrison and abandon the

battery. Thierry had, at this time, probably 200 to 300 people at the

Royal Battery to be transferred. Some of these may have been residents

of outlying settlements who repaired to the battery when the alarm

sounded. (One account indicates that the garrison there was made up of

300 soldiers and gunners, including 90 militia under a Captain Petitpas.

But Duchambon, in his report to the minister written at Rochefort,

implied that Thierry's company amounted to 200 men.) Thierry spent the

remainder of the evening of 11 May attending to the cannon and arranging

for the transfer of the supplies and ammunition. About midnight, he and

his troops arrived in town by chaloupe.29

In their apparent haste to abandon the Royal Battery, Thierry's men

had spiked the cannon poorly, had left the gun-carriages mostly intact,

and had not dumped the excess shot into the harbour as the council had

ordered. So hurried was the withdrawal that a barrel of gunpowder,

carelessly ignited, exploded, nearly killing several persons and burning

the face and robes of a récollet friar. Also in the haste, it seems that

12 men were left in each of the towers, Thierry apparently neglecting to

alert them of his departure. These men found a chaloupe in a

creek near the battery and arrived in town about two o'clock in the

morning. The next day, 12 May, Duchambon sent Lieutenant St. Etienne and

Ensign Souvigny, with about 20 men, to complete the removal of the

stores and ammunition Thierry had left behind; "ce qu'ils firent" wrote

Duchambon, "a Lexception de tous Les Boullets de canon et Bombes qui y

ont resté n'ayant pas peu Les emporter."30 The clean-up work

was undoubtedly hurried by the burning that day of the northeast harbour

storehouses.

The habitant de Louisbourg could not understand the decision

to abandon the Royal Battery, "si ce n'est une terreur panique, qui ne

nous a plus quitté de tout le Siege." He bemoaned that "Il n'y avoit pas

eu encore un seul coup de fusil tiré sur cette batterie, que les ennemis

ne pouvoient prendre qu'en faisant leurs approches comme pour la Ville,

& l'assiégeant, pour ainsi dire, dans les régles." He acknowledged

that a breach existed on the landward side, thus endangering the

battery, but "le crime est encore plus grand, parce que nous avions eu

plus de loisir qu'il n'en falloit, pour mettre ordre à

tout."31

Many Frenchmen undoubtedly sympathized with the habitant's

view, but his argument that the battery could only have been taken "by

making approaches in the regular way" is tenuous at best. The work was

completely exposed to the heights behind it. Cannon placed on those

heights by the provincials would have immediately commanded the position

and rendered it indefensible regardless of breaches. In any case, by the

morning of 13 May, the Royal Battery stood empty.

6 The New England camps.

(Public Record Office, Great Britain.)

|

The Provincial Army Encamps

The evening of 11 May was pleasant for the soldiers of the provincial

army encamped before Louisbourg. The weather was fair, a fresh southwest

wind rustled the grass and trees, and while the men had expected a

greater resistance to their landing, they were pleased with the results

of the day's activities. For hours, clusters of men had been straggling

back from their first curious look at the great fortress they had come

to conquer, bringing with them cows, sheep, horses, and whatever else

they could drive or carry. The expedition was a magnificent adventure

for most of them, and many believed, as did Samuel Curwen, merchant

turned warrior, that "our campaign will be short, and [we] expect the

place will surrender without bloodshed." In the morning, when the rest

of the army landed, they would show the French how well New Englanders

could fight; for the moment there was mainly "singing and Great

Rejoicing."32

Their bivouac that first night was a makeshift affair, the men

resting as best they could until the army could be assembled on shore.

Major General Wolcott noted in his journal that "our men lay in the

forest without any regular encampment." There were as yet no tents on

shore and shelters were improvised from whatever materials were at hand,

one soldier writing that "wee Cut A few boughs to keep Us from the

ground." After the cramped holds of the transports, even this was a

"most Comfortable Nights Lodging."33

The rest of the army came ashore unopposed on 12 May and about noon

"proceeded toward the town & campt." A more permanent encampment was

then begun, its construction taking several days. The men laboured in

the woods cutting timbers for storehouses, shelters, and fires, one New

Englander admitting that there were "More Conveniences for our Living on

the Island Than was Represented to Us."34

Much uncertainty exists about the location of this encampment. The

instructions Shirley gave to Pepperrell stated that "the first thing to

be observed [after all the troops have been landed], is to march on till

you can find . . . a proper spot to encamp them on; which must be as

high as possible to some convenient brook, or watering place." The

encampment was probably located at, or near, Flat Point. Here Flat Point

Brook (called "Freshwater Brook" on contemporary maps), flowing roughly

north and south, empties into Gabarus Bay and offers a considerable

source of fresh water. The official account of the campaign states that

"the camp was formed about half a mile from the place where they [the

troops] made a feint of landing," and Benjamin Green, Pepperrell's

secretary, says that they camped "about 1-1/2 miles from the town." This

would put the encampment in the vicinity of Flat Point. Benjamin

Cleaves, in his journal, also hints that the encampment might have been

in this area.35

There is some evidence to indicate that the camp might have been

relocated soon after the army moved to the Flat Point area. Two

contemporary maps show the location of the provincial camp. One map

shows it on either side of Flat Point Brook; the other shows it directly

on Flat Point itself.36 No explanation for the disparity

between the two maps has been found, but Green noted that on 13 May the

camp was moved, "the enemy's balls having disturbed us the last

night."37 The distance from Louisbourg to Flat Point seems

rather far for the provincials to have been greatly bothered by cannon

shot, but Cleaves confirms Green's statement and adds that in the night

a new camp was built. It is therefore possible that two camps were

started — one around Flat Point Brook, and, when this camp proved

to be within range of French cannon, another on Flat Point itself. We do

not know where the provincials were when the French shot began to

disturb them. They may have been beyond the Flat Point area and then

fell back, and the disparity in the maps might be nothing more than two

generalized representations of the same encampment.38 The

arrangement of the permanent encampment is equally uncertain. Shirley's

instructions as to the manner of laying out the camp specified that,

as soon as [a proper spot to encamp the army has been found], and

the ground marked by the Quarters-Masters, who should have, each,

colours to distinguish each regiment, the tents must be pitched, in the

usual form and distance, if possible; and at the front of every

regiment, a guard with tents, which is called the quarter guard, and

mounts in the morning, as the picket guard turns out at sun set and lays

on their arms.39

Whether the encampment was established precisely on the lines Shirley

envisioned has not been determined, but Colonel John Bradstreet, a

regular army officer who was usually very critical of the provincial

soldiers because they lacked proper military training and discipline,

remarked that "with as much dispatch as could be expected, all the

Troops, cannon, and Baggage were landed and properly Incamped

[italics mine]."40 Bradstreet's statement offers a clue to

the manner in which the encampment was laid out. To a regular officer

like Bradstreet, being properly encamped would probably have meant

encamping according to division (or, in this instance, regiment), with

proper intervals between, and a protective picket line drawn up about

the front and flanks to guard against a sudden attack by the

enemy.41 This is the type of arrangement Shirley seems to

have had in mind. There is, however, little direct evidence to

substantiate that the encampment was so arranged. The official account

merely states that at first the camp was formed "without throwing up

[picket] Lines; depending only upon their Scouts and Guards [for

protection]. But afterwards they encamped regularly [italics

mine], and threw up Lines."42

The provincials maintained their encampment in the Flat Point area

throughout the siege. While all of the regiments would have been

initially assembled at the encampment, only five regiments appear to

have been permanently headquartered there during the progress of the

campaign. These were Pepperrell's (including his personal headquarters),

Burr's (nominally Wolcott's), Moulton's (which returned from Port

Toulouse on 16 May), Moore's and Willard's.43 Soldiers from

these regiments, however, were later posted to the ranks of the

remaining four regiments (Hale's; Richmond's, Waldo's and Gorham's, plus

Dwight's artillery train), which subsequently sustained the several

batteries erected against Louisbourg. These latter regiments encamped at

or near the batteries they sustained. No information has been found

concerning the location of Dwight's artillery train during the siege;

it, like the soldiers of certain of the regiments, probably was

scattered among the various batteries.

Duchambon Prepares for Defence

While the provincials laboured to prepare a camp, Duchambon prepared

for the ordeal ahead. He had all the entrances to the town secured; and

the soldiers who had been completely out of hand for the past five

months now swore resolutely to defend the fortress to the last man

before they would allow it to fall into English hands.44

Duchambon posted them according to their individual commands.

Duvivier's company, under the command of de la Vallière, was posted

at the Maurepas Bastion with de La Rhonde's company, which held the

Maurepas gate near the loopholes (meurtrières). Bonnaventure's

company was at the Brouillan Bastion and the crenellated wall. With

Bonnaventure were Schoncher's Swiss companies, guarding the loopholes of

the Princess Demi-bastion. At the Princess Demi-bastion and as far as

the Queen's gate was d'Espiet's company. Duhaget's company sustained the

Queen's Bastion, Villejoint's company the King's Bastion, and Thierry's

company the Dauphin Demi-bastion.

De Gannes' company held the Pièce de la Grave fronting the

harbour. De Gannes retained command here until 23 June, when he

transferred to the Island Battery to replace its commander,

d'Ailleboust, who returned to the town because of illness. D'Ailleboust,

when sufficiently recovered, would take over command at the Pièce de

la Grave. Sainte-Marie, artillery captain, was in charge of the

cannon, while Port Captain Morpain was given the general supervision of

all the posts.45

On 12 May, Bigot and Duchambon decided to sink all the armed ships

then in port to prevent them from being captured by the provincials.

Accordingly, Ensign Verger, along with five soldiers and a number of

sailors, was ordered to sink those which were opposite the town, and

Ensign Bellemont was instructed to carry out a similar operation at the

back of the bay. Bellemont was also ordered to retrieve the oil from the

lighthouse tower. These orders seem to have been carried out by 16 May.

It was probably at this time, if not earlier, that the casemate doorways

were covered over with wood timbers in preparation to receive the women

and children.46

Duchambon, realizing that his present force was inadequate to hold

out indefinitely against the provincial army, on 16 May sent an urgent

despatch to Lieutenant Paul Marin in Acadia to come immediately with his

detachment of French and Indians. Marin possibly could have reached the

fortress in 20 to 25 days, but the messenger had such a difficult time

locating him that by the time Marin eventually arrived, Lousibourg had

fallen. Duchambon would later claim that had Marin arrived 15 or 20 days

sooner, the New Englanders would have been forced to raise the

siege.47

The Provincials Occupy the Royal Battery

The provincials took possession of the Royal Battery on 13 May.

Governor Shirley had considered the capture of this battery to be of

considerable importance to the success of the expedition. He called the

work "the most galling Battery in the harbour," and felt that its

capture would expose the whole harbour to attack by sea. Shirley

believed the battery to be lightly defended and that with an attack upon

a low part of the wall "that is unfinished at the east end" (i.e., the

left flank where the épaulements had been taken down the previous

year), "it is impossible to fail of taking [it]." Colonel John

Bradstreet, "with 500 Chosen Men," was to have made the attack the night

following the landing, but the attack was never made and the Royal

Battery was taken without firing a shot.48

On the morning of 13 May, Colonel William Vaughan, with a small party

of men, was returning from the northeast harbour (Vaughan himself said

he was trying to find the "most commodious place" to erect a counter

battery) when, passing behind the Royal Battery, he noticed that there

was no flag flying from the staff and no smoke rising from the barracks'

chimney. His suspicions aroused, Vaughan (according to many subsequent

accounts of the incident) bribed an inebriated Indian to crawl to the

battery to determine the true state of affairs. Ascertaining that the

work was indeed abandoned, Vaughan and his men took possession of it. He

then wrote to Pepperrell that "with the Grace of God and the courage of

about thirteen men I entered the Royal Battery about nine a clock and am

waiting here for a reinforcement and a flag."49

The manner in which Vaughan reputedly determined that the French no

longer occupied the Royal Battery is open to question. It smacks of

legend. The story of the Indian is not confirmed by the diaries,

journals, or testimonials of men who were there at the time. Lieutenant

Daniel Giddings of Hale's regiment, along with several men from his

company, had gone to the Royal Battery out of curiosity (independent of

Vaughan and his party) and had entered it at the same time as

Vaughan.50 Giddings recorded the incident in his journal, but

made no reference to an Indian, drunk or sober. The testimonial of

another witness, one John Tufton Mason, likewise fails to mention an

Indian, and Vaughan himself simply states that "by all Appearances [I]

had Reason to judge that said Grand Battery was deserted by the enemy,"

whereupon [we] "marched up and took."51 Until further

documentation comes to light, the story must be regarded as a tale that

adds interest but little enlightenment.

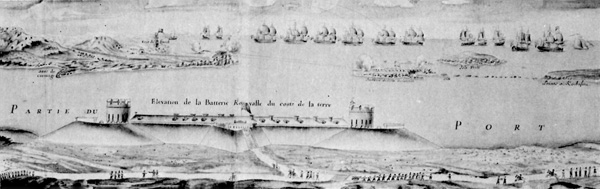

7 Louisbourg harbour from the Royal Battery. The island Battery and

Lighthouse Point are in the background.

(Bibliothèque Nationale, France.)

|

Before reinforcements could reach Vaughan, four boatloads (Vaughan

says seven boatloads) of French troops put out from the town toward the

Royal Battery. Leaving four men in the battery, Vaughan, with eight

others, ran out along the shore for "near half a Mile," and, picking up

another four men along the way, began to fire upon the French. According

to Vaughan, his little group was "within point blank Shot" of the town,

from which they were fired upon by cannon.52 The French

retired to the fortress.

That this encounter was the result of a French attempt to retake the

Royal Battery, as Vaughan and other provincial diarists believed, is

extremely unlikely. That it was meant to be an attack at all is

doubtful. French sources make no mention of such an intended attack (and

there is no reason why they should be silent about it). These men were

probably part of a force sent out by Duchambon to assist in the

destruction of those houses of the barachois area which were not

destroyed at the time of the provincial landings. One party was already

at work in the area. This force included all the militia as well as 80

French and Swiss soldiers under Captain De Gannes and a Swiss officer

named Rosser. Armed with hatchets and other tools, they were to bring

back for use in the town whatever salvageable wood they could collect,

as the supply was low. As they were finishing, according to Governor

Duchambon's report, a number of provincials appeared at the

barachois and in the upper valleys ("il parut au Barrachois et

dans les vallons des hauteurs") and fired upon the French, who returned

to town.53 Vaughan himself indicates, as does one David

Woaster, then a captain of a company of volunteers, that the engagement

took place some distance from the Royal Battery and "within point blank

Shot" of the fortress. Since the French were approaching the

"Battery-Side of the Harbour," as Vaughan and other observers admitted,

it is understandable how the New Englanders might conclude that the

enemy troops were trying to retake the Royal Battery, when actually they

were going to assist the militia and soldiers in the clean-up operations

around the barachois.54

Returning to the Royal Battery, Vaughan waited for the reinforcements

and flag he had asked Pepperrell to send. In the meantime, two English

ships' flags had been found in one of the nearby houses and these were

hoisted on the staff. According to some chroniclers, one William Tufts

climbed the pole and fastened his red coat to the staff to serve as a

flag. (At least one account claims that it was another Indian that

performed this act.) This story also seems spurious, despite an obituary

notice of 3 June 1771 referring to such an exploit by Tufts at the

Island Battery, during the abortive 6 June attack.55 Perhaps

the story has its origins here.

According to at least one contemporary account, Captain Joshua Pierce

of Willard's regiment was the first to raise the English colours over

the Royal Battery on 13 May. Colonel Samuel Waldo, who soon moved into

the battery with part of his regiment, supports Vaughan's statement that

the flag raised that day belonged to a ship's ensign and was not Tufts'

coat. In a letter to Pepperrell dated 14 May, Waldo asks for one of the

Union flags, "as the fisherman's ensign gives a mean appearance." We do

not know what this "fisherman's ensign" looked like, but a French

militia officer who accompanied a number of men across the harbour to

retrieve the oil from the lighthouse tower, noticed the flag and said

that it resembled an English weathervane ("un petit pavillon comme une

Girouette angloise").56

Colonel John Bradstreet soon arrived at the battery with a

reinforcement, and reported back to Pepperrell that the place was in bad

condition but it could be repaired. Colonel Waldo, who arrived with five

companies of his regiment later that day, reported that the cannon

(twenty-eight 42-pounders and two 18-pounders) were plugged up and most

of the carriages damaged, "tho' with small repairs, all capable of

service." Bradstreet requested smiths and armourers to drill open the

vents of the cannon, and that "handpicks, ramers [sic], &

sponges & a quantity of powder" would also be needed. Many balls and

shells were found, and Bradstreet promised to have a 42-pounder ready to

open fire on the town by noon of 14 May if his needs were speedily

met.57

They seem to have been met quickly; by 10 a.m. on 14 May, the

42-pounder he promised to have ready was cleared and had opened fire.

The first shot killed 14 of the enemy. Waldo reported that 40 shot were

subsequently fired against the town, while the French return fire from

the fortress and Island Battery amounted to 146 shot and 50 shells. Only

four of the embrasures of the Royal Battery pointed against the town,

and while the fire from the Island Battery was "troublesome," Waldo

intended to concentrate his fire on the town rather than the island to

aid Pepperrell's designs against the fortress.58

The Landing of the Provisions and Artillery

While Vaughan and his men were taking possession of the Royal

Battery, the provisions and artillery were being brought ashore four

miles to the west at Flat Point. The army that went to Louisbourg was

provided with provisions for four months. Governor Shirley had asked the

Massachusetts Committee of War to compute the total number of men in the

army and fleet at 4,400 at least, and the General Assembly had before

its dissolution empowered the committee to purchase and forward

provisions for one month over and above the original four months, thus

assuring provisions for five months.59

Despite Governor Shirley's efforts, supplies were deficient. At

Canso, Pepperrell wrote Shirley that the provisions were inadequate;

that they were far less than had been expected, and that he intended to

write the war committee for additional stores. He also reported that the

troops were deficient in necessary accoutrements, though the armourers

were fitting for service what they could. Shirley promised to look into

the matter and to send Pepperrell anything that it was in his power to

send.60

Whether the deficiencies were remedied is not known, and the exact

nature and extent of the provisions initially sent has not been

determined. No invoices for these shipments have been found. From

various references in journals and letters, however, we can be

reasonably certain that the men had large quantities of rum, as well as

bread, pork, rice, beans, peas and molasses.61 Also, they

apparently had a supply of fresh meat, since there are numerous

references to cattle being butchered during the course of the siege. And

the rations were supplemented by fresh lobster and

trout.62

The provisions were brought ashore near the encampment at Flat Point.

The landing "was attended with extreme Difficulty and Fatigue," the surf

continually running high, and it was nearly two weeks before all the

stores were landed. On some days, "there was no landing any Thing at

all" because of the high surf, and "many Boats and some Stores were

lost."63 The work was even more difficult when the artillery

was brought ashore the following day, 14 May; the men were "obliged to

wade high into the water to save everything that would have been damaged

by being wet." The soldiers who brought the guns ashore "had no Cloathes

to shift themselves with, but poor Defence from the Weather, and at the

same time the nights were very cold, and generally attended with thick

heavy Fogs."64

Once ashore, the cannon still had to be moved over the difficult

marshy ground stretching between Flat Point and the

fortress.65 While several roads ran out to the east and

southeast from Flat Point (one of which roughly paralleled the coast to

the southern extremity of the Green Hill range within a mile of the

town), and while the provincials constructed additional roads after the

landing, they proved of little use, as the official account of the siege

testifies.

The transporting [of] the cannon was . . . almost incredible

labour and fatigue. For all the roads over which they were drawn, saving

here and there small patches of rocky hills, were a deep morass; in

which, whilst the cannon were upon wheels, they several times sunk, so

as to bury not only the carriages, but the whole body of the cannon

likewise. Horses and oxen could not be employed in this service; but the

whole was to be done by the men themselves, up to the knees in

mud.66

The French had regarded the marshes and bogs to the west of the

fortress as impassable, and so they might have been but for the

ingenuity of Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Meserve of Moore's New

Hampshire Regiment. Colonel Meserve believed that if the cannon were

placed on flat sledges, they could be drawn across the marshes to the

points where they would be required. He thereupon designed and had

constructed several wooden sledges 16 feet long and 5 feet wide, by

which the guns were hauled across the morass. The shot, shells and

powder, in the meantime, were transported on the soldiers'

backs.67

The Erection of the Green Hill Battery, 15 May

Meserve's sledges would come later, however, and on 14 May it was the

brawn of the soldiers that moved the heavy guns over the marshes and

inadequate roads and onto the southern extremity of Green Hill, where

the first provincial battery was to be erected. For nearly two days the

men laboured in the wind and mud, dragging and pushing the cannon and

mortars into position. By 15 May, two 9-pounder cannon, two falconets,

one 13-inch mortar, one 11-inch mortar, and one 9-inch mortar had been

mounted. Five hundred men (probably Colonel Sylvester Richmond's Sixth

Massachusetts Regiment) were ordered to support the

battery.68

The exact location of this work (referred to as the "battery on Green

Hill" or the "Green Hill battery" in the documents) has not been

determined. Duchambon, who watched as the guns were mounted, says it was

"sur la hauteur derriere les plaines vis a vis Le Bastion du Roy"

approximately 1,500 yards distant.69 Most probably it was

situated on the hill mentioned by Governor Shirley in his instructions

to Pepperrell.

About south-west from the citadel bastion, a large half-mile

distance, is a rocky hill, which in attacking of the town, may be of

great service, by covering a number of our men, and planting some cannon

there, on the top; in such a manner as when you are on the spot, you may

judge most advantageous; where you may keep the bombardiers, &c.

continually employed, endeavouring principally to demolish their

magazine, citadel, walls, &c. which are objects sufficiently in

view.70

The Green Hill battery opened fire on the fortress on 15 May.

Shirley's hope that the battery would inflict considerable damage on the

town was disappointed however. Duchambon later reported that while this

work "napas Cessé de tirer de distance en distance . . . ce feu na fait

aucun progrés . . . et na tué ny Blessé personne." The distance was too

great. In turn, the Green Hill battery sustained little or no damage

from French counterfire until 20 May, when a cannon shot fired from the

town wounded five men, one of whom lost both legs and afterwards

died.71

With the fire from Green Hill proving ineffectual, a council of war

on 16 May recommended that a battery be erected closer to the town's

west gate. Later that day the same council advised that the mortars,

coehorns and cannon at Green Hill be moved to a hill northwest of the

town, and that the proposed new battery be erected there. It further

recommended that eight 22-pounders, along with two 18-pounders and two

42-pounders removed from the Royal Battery, also be mounted

there.72 While the men were in the process of transferring

the guns, Pepperrell and Warren were preparing a surrender summons to

send into Louisbourg.

The Summons to Surrender on 18 May

On 14 May, the day the Green Hill battery was begun, Pepperrell

assembled a council of war and asked it to consider whether a surrender

summons should be sent to the commanding officer in Louisbourg. But the

council adjourned without making a decision. The same day, Colonel Waldo

at the Royal Battery wrote to Pepperrell that both he and Colonel

Bradstreet believed that the governor of Louisbourg would be justified

in hanging any messenger sent with a summons, unless the army could

present a more formidable appearance than it so far had

shown.73

In council the next day, the matter was again broached. The members

of the council initially voted to send the summons as soon as the

gunners at the Green Hill battery were ready to open fire. But at its

afternoon session, the council, possibly with Waldo's communication in

hand, decided that firing against the town should be commenced before

any surrender demands were made. Finally, on 17 May, after two days of

firing from the Green Hill and Royal batteries and over the objections

of several senior officers who still considered it unjustified, the

council voted to send the following summons to "the Commander in chief

of the French King's Troops, in Louisbourg, on the Island of Cape

Breton":74

The Camp before Louisbourg, May 7, 1745 [O.S.]. Whereas,

there is now encamped on the island of Cape Breton, near the city of

Louisbourg, a number of his Britannic Majesty's troops under the command

of the Honble. Lieut. General Pepperrell, and also a squadron of his

said Majesty's ships of war, under the command of the Honble. Peter

Warren Esq. is now lying before the harbour of the said city, for the

reduction thereof to the obedience of the crown of Great Britain.

We, the said William Pepperrell and Peter Warren, to prevent the

effusion of Christian blood, do in the name of our sovereign lord,

George the second, of Great Britain, France and Ireland, King &c.

summon you to surrender to his obedience the said city, fortresses and

territory, together with the artillery, arms and stores of war thereunto

belonging. In consequence of which surrender, we the said William

Pepperrell and Peter Warren, in the name of our said sovereign, do

assure you that all the subjects of the French king now in said city and

territory shall be treated with the utmost humanity, have their personal

estate secured to them, and have leave to transport themselves and said

effects to any part of the French king's dominions in Europe.

Your answere hereto is demanded at or before 5 o' the clock this

afternoon.

W. Pepperrell

P. Warren75

Early on the morning of 18 May, Pepperrell ordered a general

cease-fire. The batteries fell silent, and as the provincial soldiers

stood to arms, the walls of the fortress were crowded with women and

children who joined their men to get a glimpse of the besieging army.

From the provincial lines at about 11 o'clock appeared a Captain Agnue,

accompanied by a drummer and a sergeant bearing a flag of truce. The

captain carried the surrender summons. Entering the town through the

Dauphin Gate, Agnue was met by Port Captain Morpain, who blindfolded

and escorted him to the office of the Commissaire-Ordonnateur, François

Bigot, where the summons was delivered to Duchambon.76

Duchambon's reply was firm, and vindicated the view of the provincial

officers who considered the summons premature. He said that he would not

consider any such proposition until the English army had made a decisive

attack and until he was convinced that the fortress could not be held.

Until then, the only answer he would offer would come from "La Bouche de

nos canons."77

Duchambon's refusal to surrender the fortress caused little

disappointment among the soldiers of the provincial army. One volunteer

happily wrote that "Seeing the Terms was not Complied with We Gave a

Great Shout and Began to fire Upon the town Again."78 They

had come to fight and fight they would.

French Sortie of 19 May and the Proposed Provincial Assault on

Louisbourg of 20 May

As the war council of 16 May had advised (since the fire from the

Green Hill battery was ineffectual), a second battery was begun under

the direction of Captain Joshua Pierce of Willard's regiment. This work,

called the Coehorn or Eight-Gun Battery, was situated approximately 900

yards northwest of the King's Bastion. By 22 May it mounted four

22-pounder cannon, as well as the 9- and 11-inch mortars from the

battery on Green Hill. Four more 22-pounders were added on 26 May, along

with the 9-pounders and the 13-inch mortar from Green Hill. The

provincials brought additional cannon from Flat Point, probably hauled

at night on Meserve's sledges.79

On the night ot 19 May, a French party made a sortie from the

fortress with the possible intention of hindering the men transporting

the guns to the Coehorn Battery. Very little is known about this sortie

(its exact point of origin and its purpose), but it was repulsed and its

failure seemed to dissuade Duchambon (at least for the moment) from

making any more such attacks. Duchambon's officers voted flatly against

further sorties on the grounds that it was difficult enough to defend

the ramparts with the 1,300 men they did have. The did not wish to risk

them in attacks that might prove futile at best. Besides, while the

soldiers professed loyalty and submitted to authority now, they still

faced charges of mutiny and insubordinate behaviour. Who could tell what

they might do if they had the opportunity to escape from the punishment

of a crime which was rarely pardoned?80

The morning after the sortie, 20 May, a decision of another sort was

made in the provincial camp. Another council of war met and announced

that Louisbourg would be attacked by storm that night. The soldiers

learned of the attack about 10 a.m. and the subalterns objected

strongly, preferring a longer bombardment of the town before considering

such an assault. Great uneasiness pervaded the army as the men talked

about the council's decision. Commodore Warren, on shore with a number

of his sailors who were to participate in the attack, noticed the

general temper of the men and feared the consequences of an assault made

by such unwilling soldiers. He talked with Pepperrell for some time, and

afterward the company captains were asked to meet with the council in

the afternoon and give their opinions on the proposed

attack.81

Apparently the captains were as much opposed to the idea as the

lieutenants and enlisted men, for after the meeting the council

announced that the assault had been cancelled. The council advised

officially that "as there appears a great dissatisfaction in many of the

officers and soldiers at the designed attack on the town by storm this

night, and as it may be attended with very ill consequences because of

this dissatisfaction, the present attack is to be deferred for the

present."82 The army would wait for the cannon to open a

breach in the walls.

|