|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

The Battle of the Restigouche

by Judith Beattle and Bernard Pothier

The Battle

The Louisbourg squadron, under Byron, made contact with the French on

22 June when the Fame was anchored alone off Miguasha Point (most

of the squadron having been dispersed by fog). Four of its boats

captured an armed reconnaissance schooner which the French had

previously taken as a prize.1

Failing instructions from Montreal, Giraudais was forced —

albeit reluctantly — to initiate on his own the defense of a

position in which he unequivocally held strategic and tactical

advantages. His forces comprised the Machault, 26 guns (but only

14 mounted on 8 July, the day of the final engagement); the

Bienfaisant, 16 guns mounted: the Marquis do Malauze, 12

guns mounted; six English ships captured in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,

and 25 to 30 Acadian sloops and schooners from the Miramichi and

elsewhere whose crews had joined the French when they learned of the fleet's

arrival in the Restigouche. In terms of manpower, the French had 200

regular Troupes de la Marine (infantry under the authority of the Navy

Department) under D'Angeac; 300 Acadians capable of bearing arms, "tous

adroits mais paresseux et indépendants s'ils ne sont

gouvernés,"2 and 250 Micmacs. Nevertheless, the capture of

the reconnaissance schooner marked the inauspicious beginning of a

particularly inept military effort by the French.

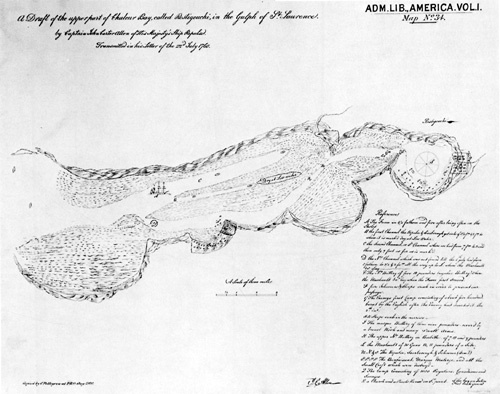

3 "A Draft of the upper part of Chaleur Bay, called Restigouchi, in

the Gulph of St. Lawrence, by Captain John Carter Allen of His Majesty's

Ship Repulse. Transmitted in his letter of 22d July 1760."

A The Fame. . . .

B the first Channel. . . .

C the Second Channel, or So. Channel. . . .

D the No. Channel. . . .

E The No. Battery. . . .

F five Schooners & Sloops sunk . . . to prevent our passage.

G The Enemys first Camp. . . .

HH Sloops sunk in the narrows.

I The masque battery. . . .

K The upper No. Battery en Barbette. . . .

L The Machault. . . .

M, N, & O. The Repulse, Scarborough, & Schooner. . . .

P.P.P.P. The Bienfaisant, Marque Malorge, and all the Small Craft which were destroy'd.

Q The Camp consisting of 1000 Regulars, Canadians and Savages.

R a Church and a Priests House on So. point.

S the bay an Intire Flat boats ground.

A Scale of three miles."

(Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

23 June

Byron weighed anchor on the morning of 23 June and set out for the

head of the bay in search of the enemy, but the vagaries of the

unfamiliar shallow channel soon compelled him to abandon the cumbersome

Fame. Resuming his navigation in the Fame's boats, he soon

"saw sevl ships & vessls at anchor above them about 2 leag near a

point of land (on the Northern shore) . . . a frigate . . . 2 others

seemed to be Merchant or Storeships the others sloops and schooners in

all 10 or 12 sail. . . ."3

24 June

At dawn the next day Byron dispatched two boats to make further

soundings, but within two hours they were compelled to return to the

flagship with several French boats in pursuit.

On 24 June Giraudais set his men to the rapid completion of the

battery, being built en barbette, that he had begun on the north shore

at Pointe à la Batterie. He transferred four 12-pounders and one

6-pounder from the Machault, his flagship, to the battery and

appointed his second in-command, Donat do la Garde,4 to

command the position. As a mobile supplement to the shore battery,

Giraudais retained the Machault in readiness in the channel,

close behind a chain of small sloops and schooners which he scuttled

one-half cannon-shot below the battery.

The 60 men and seven women taken prisoner on their way to Quebec City

in May, although "well used before the English ships appeared," were

now packed into the hold of a small schooner for security reasons. According to the

moving testimony of the prisoners, they were henceforth

without air, without light, strongly guarded by a party of

soldiers, under the cannon of the battery; our cloaths and beds taken

from us; we had not room to stretch ourselves . . . [with] very

little provisions and only brackish water to drink.

...5

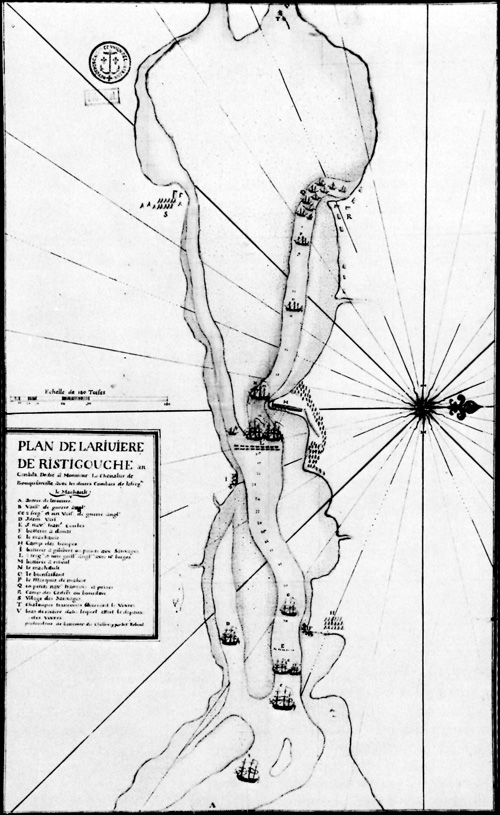

4 "Plan de lariviere de Ristigouche au Canàda. Dedié a Monsieur le

Chevalier de Bouquinville, avec les divers Combats de lafreg[ate] le

Machault

A antrée de larviere

B Vaiss[eaux] de guerre angl[ais]

CC 2 freg[ates] et un Vais[seau] de guerre angl[ais]

D Idem Vais[seau]

E 5 nav[ires] fran[çois] coules.

G batterie à donat

G le machault

H Camp des troupes

I batterie a gilibert ou pointe aux Sauvages

L 2 freg[ates] et une [goélette] angl[ais] avec 16 berges.

M batterie a reboul

N le machault

O le bienfaisant

P Le Marquis de malose

Q 10 petits nav[ires] françois et prises

R Camp des Cadies ou bourdon

S Vilage des Sauvages

T Chaloupes françoises Chariant le Vivres

V bras de rivière dans lequel ettoit le depaux des Vivres.

profondeur de bassemer en Chiffres. par le Sr Reboul,

Echelle de 180 Toises."

(Bibliothéque Nationale/Ministère de la Défense [Marine],

from a copy in the Public Archives of Canada.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

25 June

On 25 June the Fame weighed anchor and attempted to move

closer to the head of the bay; however, at low water, at noon, it went

aground "on a patch of mud,"6 "where I thought we never

should have got off again."7 It did get off, but only after

nine or ten hours of arduous effort and jettisoning "one of her anchors

for the present,"8 and with the help of the schooner

recaptured earlier off Miguasha Point.

It is difficult to comprehend Giraudais's failure to capitalize on

the definite tactical advantage of having his adversary aground on the

shoals. Decisive action by the French on 25 June might have

altered the outcome of the encounter. However, the French commander

was not altogether unmindful of his advantage. As Byron learned later,

Giraudais has actually contemplated sending a boarding party to the

Fame,9 but had changed his mind when he perceived the

man-of-war to be a fully armed two-decker.

The Fame's admittedly formidable firepower notwithstanding,

the French held enough of the classic advantages of a war situation to

virtually guarantee their success; they enjoyed adequate manpower, the

advantages of a secure defensive position, mobility both on land and on

water, surprise, and for at least two hours before the Fame was

released from the shoals, darkness. Their only serious disadvantage,

albeit an essential one, was the low morale of both officers and men.

Disheartened by the events both in Europe and North America in the

previous two years which undermined France's position, neither

Giraudais nor D'Angeac, any more than their subalterns, possessed the

energy or bold offensive spirit which, combined with their physical

advantages, might have led to a decisive French victory on the

Restigouche in 1760.

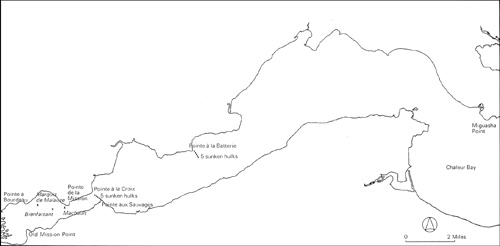

5 Restigouche River, showing the location of land and

water sites.

(Map of S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

26 June

On 26 June the rest of the English squadron came into view off

Miguasha Point. While the captains of the ships of the line, the

Achilles and the Dosetshire, realized they were facing an

unknown channel and prudently anchored east of the point, the captains

of the frigates, the Scarborough and the Repulse, at first

took the Fame to be French and endeavoured to get up to it. The

enthusiasm of both Captain Scot and Captain Alien was exceeded only by

their brash disregard of the navigational realities under which they

were to labour. Both frigates ran aground and although the

Scarborough was soon released thanks to assistance from the

Fame, the Repulse was forced to spend the night on the

shoals.10

27 June

His squadron at full complement now, on 27 June Byron ordered the

Fame's boats and the captured schooner to search for the elusive

channel. The Scarborough, the Repulse and the Fame

cautiously took up the rear.11 The most serious disadvantage

of the English, given the low morale of the French, was the hazardous

navigation. The channel ran very close to the north shore and was

therefore exposed to the French guns and musketry. It was also, as Byron

put it, so narrow there was "no room for a ship to

swing."12

28 June

When, on 23 June, the captured schooner went aground in less than a

fathom,13 it was clear that the English had unwittingly

penetrated into a cul-de-sac. At the same time, the Repulse and

the Scarborough lay aground within range of the French guns at

Pointe à la Batterie. Giraudais gave the order to open fire, but the

French action was limited to a rather passive and half-hearted effort

and their fire caused little real damage to the English. Nevertheless,

coupled with musketry from a detachment of regulars, Acadians and

Miemacs hidden in the surrounding woods, it harrassed the English in

their efforts to get the ships afloat. However, the powerful artillery

of the Fame was brought to bear on the French position as a cover

for the grounded frigates and by evening the French musketry was

effectively dispersed.

Giraudais reverted to the defensive once again, ordering the

Marquis de Malauze and the Bienfaisant as far upstream in

the Restigouche as possible in order to protect their

cargoes.14 He brought the Machault to the mouth of the

river only slightly beyond the range of the English guns, later

explaining; "Javois medité de resté avec ma fregatte Pour Soutenir la

Batterie mais la force de l'Ennemis Estant trop Supérieure Maurois

Empeché de regoindre tous les Batiments que Javois fait

monter.15

As a further precaution, Giraudais ordered the English prisoners

transferred from their prison aboard a schooner to the more secure hold

of the Machault where they apparently underwent more severe

treatment than previously.

The sailors were put into irons, and the captains and merchants

had an old sail to lie on, spread on a row of hogsheads. Our allowance

was bread and wine with two ounces of pork per day; but, thank God, our

appetites were not very keen; and if we complained that we were stifled

with stench and heat, and eat up with vermin, they silenced us with

saying, "Well, you shall go on shore under a guard of Indians..." after

telling us the savages had sworn they would scalp us every soul; they

told us also, that, if we made the least noise, they would point four

cannon into the hold and sink the vessel, or burn us like a parcel of

rats.16

The search for a navigable channel remained Byron's essential first

objective. He might well have dispensed with this exercise given the

inability of the French to undertake a spirited defensive effort.

Indeed, had he been willing to depart from the classical norm. Byron

could well have landed a party, routed the French on shore, and then

proceeded to harass the enemy squadron unimpeded.

The fact that even Byron's captured schooner, of low draft, had run

aground while the Machault had retreated upriver with relative

ease was sufficient indication that considerable further effort was

required before a passage could be found. Thus the soundings continued

and during the night of 28-29 June a new and apparently promising

channel was discovered close to the south shore of the Restigouche.

29 June

Byron immediately ordered the Repulse and the

Scarborough to swing back and attempt the new passage, but

further sounding soon belied his premature optimism. The passage, the

"So[uth] channel" of the Allen map (or, more accurately, "le faux chanal

du Sud" as Giraudais called it17), was not a channel at all,

but another cul-de-sac which from an impressive seven fathoms had

quickly fallen to nine feet before running into mud flats at low

water.

With the transfer of English efforts to the south channel on 29 June,

the Repulse and the Scarborough fell beyond the range of

the French guns at Pointe à la Batterie;18 however, the

battery remained within range of the powerful guns of the Fame

which enjoyed the further and more significant advantage of firing at

the unprotected French flank.19 Although the French at first

returned the Fame's fire, they were overwhelmed within a few

days.

2 July

By noon on 2 July, the Fame had smashed the easternmost French

gun and a short time later the French began "making off from

thence."20 Their retreat was premeditated and orderly for the

remaining four guns were spiked, "split and burst to

pieces."21

When the English landing party put ashore at Pointe à la Batterie,

not a Frenchman remained in sight. The gun carriages and other woodwork

at both the battery and the adjoining camp were burned and the English,

carrying their fury still further, also burned between 150 and 200

buildings which the Acadian refugee community had recently

built.22 This spirited action was the first decisive factor

to affect English fortunes. Nevertheless, Byron declined his newly

acquired land bridgehead, opting rather to maintain his original aim of

finding a navigable channel and effecting the essential task of

destroying the French squadron.

Following their withdrawal from Pointe à la Batterie on 2 July, the

French reassembled at Pointe à Bourdeau where Giraudais ordered the

establishment of a new camp and the unloading of his storeships. In an

effort to stop the English advance, he ordered two new batteries erected

at the mouth of the river, one on Pointe aux Sauvages (now within

Campbellton) and the other across the narrows at Pointe de la

Mission.

3 July

The day after the reduction of Pointe à la Batterie, Captain Allen of

the Repulse dejectedly withdrew from the south channel. As he and

Byron were discussing alternatives aboard the Fame on the evening

of 3 July, "giving up all hopes of finding a channel,"23 word

came that a new passage had been found close to the north shore where

soundings had resumed the night prior to the French withdrawal from

Pointe à la Batterie.

Heartened by this breakthrough, Byron ordered the Repulse, the

Scarborough and the schooner (now armed with four 6-pounders and

manned by 50 men) to prepare to move into the new channel. During the

night of 3-4 July the English squadron began moving toward the river

mouth, but it was two days before a passage could be cleared through the

chain of hulks the French had sunk below Pointe à la

Batterie.24

5 July

As soon as the English had cleared the chain of hulks below Pointe à

la Batterie, on 5 July, Byron ordered the armed schooner against workmen

he saw at the site of the new battery at Pointe aux Sauvages "to annoy

them all he could with his great guns."25 However, Lieutenant

Cummings, the commander of the schooner, anchored too close to the

shore, well within range of the deadly musketry which suddenly began to

rain from the barely completed breastwork and the surrounding woods and

was forced to draw back to safety. Cummings himself was seriously

wounded, barely escaping with his life.26

6 to 7 July

Maintaining his original aim of protecting his cargos, during the

night of 6-7 July Giraudais sank a second chain of five hulks across the

channel at the narrows between Pointe aux Sauvages and Pointe à la

Croix.27 The English remained undaunted and showed every sign

of continuing hard after the French. Giraudais then decided to transfer

his prisoners from the Machault to the hold of the Marquis de

Malauze, less vulnerable to immediate fire from the attackers.

D'Angeac noted the transfer in his report; "Nous nous étions debaracé

des prisonniers que nous avions à bord du Machault en les envoyant à

bord du Marquis de Maloze avec un détachement de vingt-cinq hommes et un

Sergent et un Sergent de Confiance [sic] pour leur

garde."28

When the English schooner again attempted to reduce the Pointe aux

Sauvages battery on 7 July not only did it have concealed sniper muketry

to contend with as before, but also the fire of three 4-pounders which

now stood at the ready. In the face of superior firepower, a better

position and a spirited French defense, the English again suffered the

indignity of a hasty retreat to the safety of the

frigates.29

Across the narrows at Pointe de la Mission another party of labourers

had been busy erecting a second battery, en barbette, with an ordnance

of three 12-pounders and two 6-pounders and a supporting detachment of

30 sharpshooters. This battery was ready to fire in the afternoon of 7

July.30

In the course of the night of 7-8 July, the Repulse and the

Scarborough, preceded by the schooner, continued their advance

and their survey of the channel. Although it is not clear how the

English managed to skirt the second chain of hulks, they did so during

the night of 7-8 July. Despite intermittent fire all night from both

batteries and the musketry, at daybreak the schooner, the Repulse

and the Scarborough all stood in the Restigouche, upstream from

the French chain of hulks and face to face with the Machault.

8 July

As dawn broke on 8 July, Giraudais saw with dismay from the bridge of

the Machault that the two English frigates and the armed schooner

stood at anchor only one-half cannon-shot downstream. The engagement

which the French had ardently hoped to avoid was inevitable and

imminent. To the 32 guns of the Repulse, the 20 of the

Scarborough and the four of the schooner were opposed the ten

starboard 12-pounders of the Machault,31 the three

4-pounders at Pointe aux Sauvages and the five guns at Pointe de la

Mission. Every man who could be spared from manning the French

artillery, guarding the prisoners in the Marquis de Malauze, and

other tasks essential to the immediate defense of the French position

was dispatched to disembark cargo from the two storeships and to tow a

score or more smaller vessels within range of the French sharpshooters

lining the north shore of the river.32

Shortly after five o'clock in the morning, the Repulse, now

within range of the French battery on Pointe aux Sauvages, quickly drove

the defenders from their position. As the frigates moved slowly upstream

they were met by brisk fire from the battery on Pointe de la Mission

and, close by, from the Machault.33 The French fire

was so brisk that the Repulse, in the lead, was driven "aground

in a very bad position with her head on to the shoals."34 The

French fire inflicted such heavy punishment upon the Repulse that

Giraudais claimed that technically his guns had sunk it.35

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine how the Repulse, had it been

standing in deep water rather than aground on the shoals, could have

avoided sinking.

Far from being able to capitalize on the enemy's discomfort, the

Machault, in an incredible example of military unpreparedness,

was almost out of powder and cartridges.36 As a safety

precaution Giraudais had earlier transferred part of his war stores to a

smaller vessel and to this vessel he hastily dispatched one of his

boats. However, the terror of the moment affected its crew for they were

never heard from again although the boat, fully laden as ordered, was

later found abandoned.

As its powder supply dwindled the Machault's fire became more

sporadic until it ceased at nine o'clock. The powder situation being

compounded by the presence of seven feet of water in the hold, Giraudais

determined to abandon ship37 and at 11 o'clock the

Mchault struck its colours.

In the meantime the Repulse had managed to get off the shoals,

and, with the Scarborough, resumed firing on the French battery

at Pointe de la Mission. The latter's fire had virtually stopped when

the Machault had struck its colours, but resumed at intervals

"not more than one or two guns in a quarter of an hour."38

The English frigates were unable to move higher because of the shallow

water.

Under ordinary circumstances, the tactic of storming the moribund

Machault would have suited the occasion; however, Captain Allen

of the Repulse surmised that the French intended to blow it up

rather than turn its cargo over to the enemy. Given his irreversible

advantage at this juncture, Allen accordingly hold back his boats in

order not to run unnecessary risk.39

Shortly before noon, Giraudais and D'Angeac, their determination to

remain to the last aboard their flagship honoured now, descended into a

boat and made for the French camp at Pointe à Bourdeau. Their orderly

retreat did not even lack an appropriate flourish of enemy fire, "ayant

pendant une partie du chemin les boulets à nos

trousses."40

At or around noon the Machault blew up with a "very great

explosion."41 Presumably the charge had gone off prematurely

for several Frenchmen were wounded. Fifteen minutes later the

Bienfaisant similarly blow up, its entire cargo still in its

hold.42 The Marquis de Malauze would undoubtedly have

suffered a similar fate had the prisoners not been within its hold. The

prisoners, now numbering 62,43 had heard the "two terrible

reports." Shortly after, they were brought up on deck and ordered into

an inadequate makeshift raft "which would have sunk with one half of our

number." Half-crazed by the prospect of delivering themselves into the

hands of the Micmacs on shore, the prisoners refused to move and finally

prevailed upon their captors to admit that to force them to leave would

amount to sacrificing them to the Indians. The French therefore left

them to their fate, but not before marching them back into the hold

where they were fettered and handcuffed anew and the hatches again

secured above them.44

The prisoners were "almost mad with fear, expecting every moment to

be blown up," helpless in their dark and stifling prison. When a

bulkhead was finally knocked down and the hatches forced open, what

greeted them on deck was hardly more reassuring; dense smoke from the

burning Machault and Bienfaisant stood between them and

recognition by their compatriots beyond and "all the shore was lined

with Indians, firing small arms upon us. Although fortunately out of

musket range for the time being, they were in terror of night. "We were

in the utmost perplexity to get away, because we knew, had we remained

aboard that night, we should have been boarded by the Indians, and every

man scalped."45

Ironically, the prisoners were responsible for the single most

valiant feat of the entire Restigouche incident. A young follow among

them "who could swim very well" offered to set off for the

Repulse, a full league downstream. Passing under the guns of the

Pointe de la Mission battery, he arrived safely at the English frigate.

Captain Allen immediately dispatched Lord Rutherford with nine boats

escorted by the schooner to the Marquis de Malauze to the relief

of the prisoners. Not withstanding brisk fire from the one remaining

French position, the English prisoners were all released and brought to

the Repulse by mid-afternoon on 8 July.46

The English, determined to destroy every French vessel within their

reach, set the Marquis de Malauze ablaze as soon as it was

cleared of the prisoners. Like the Bienfaisant, its cargo of

"wine and brandy, bales of goods and warlike stores" was jettisoned

entirely. The efficiency of this aspect of the English operation was

marred only by the death of six Englishmen, including a midshipman who,

in spite of repeated calls to, had tarried too long with the liquor and

went down with the flaming hulk.47

Rutherford's men continued their destruction of all available French

shipping and by nightfall French losses totalled 22 or 23 vessels which,

with the exception of the Machault, the Bienfaisant and

the Marquis de Malauze, were mainly Acadian sloops, schooners and

small privateers. (These figures do not include the ten vessels the

French scuttled in the channel.) Like the Machault and the

Bienfaisant, many had been fired by the French in order to avoid

their falling into the hands of the enemy. One English source claims

that of all the vessels in French hands on the morning of 8 July, only

one schooner and two shallops remained by nightfall.48

6 "On the River Restigouche, looking down towards the Peak of

Campbellton."

[Canadian Illustrated News, 19 August 1882, p.

120.)

|

7 "Looking up the Restigouche from Le Petite Rochelle [near Pointe à

Bourdeau]."

[Canadian Illustrated News, 19 August 1882, p. 120.)

|

Having thus burned and destroyed or caused to be destroyed everything

within their reach in complete fulfillment of the aim of the

expedition's singleminded commander, the Repulse, the

Scarborough and the armed schooner swung around at 11 o'clock on

the evening of 8 July and withdrew downstream. The French fleet

destroyed, Byron did not even silence the empty tauntings of the one

remaining enemy position, the Pointe de la Mission battery. After

pausing off Pointe à la Batterie while rum was issued, Byron's squadron

sailed. On 14 July, near Paspébiac, they met Wallis's squadron from

Quebec which had been searching the lower St. Lawrence and the gulf for

the French ships, then continued on their way, four to the Fortress of

Louisbourg and the Repulse to Halifax, "her rigging, masts and

hull much shattered and no stores left at Louisbourg."49

After the unexpected and overwhelming attack of the British, the

French were left to salvage what they could of the situation. Most of

their ships' cargoes had been lost, many men had been

killed,50 and only a few boats were left to cross a large

ocean. When St. Simon returned with Vaudreuil's instructions, the French

had little means with which to implement them.

|