|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 3

Comparison of the Faunal Remains from French and British Refuse Pits at Fort Michilimackinac: A Study in Changing Subsistence Patterns

by Charles E. Cleland

Bone from French and British Refuse Pits

The number of both identified and unidentifiable

mammal, bird and fish bones from the French and British features at Fort

Michilimackinac is shown in Table 1. In all instances, bone preservation

was excellent so that fragile fish bone was as well preserved as dense

mammal bone. The fragmented condition of much of the bone accounts for

that part of the sample which could not be identified beyond class.

Tables 2 and 3 are lists of the identified species represented in the

pits of the French and British period structures respectively. The

French sample contained 317 identified bones representing 8 species of

mammals, 23 species of birds and 5 species of fish. The slightly larger

British sample of 363 identified bones represented less diversity with 8

species of mammals, 16 species of birds and 4 species of fish.

Table 1: Identified and Unidentifiable Bone From

French and British Storage Pits at Fort Michilimackinac

|

| French |

|

| Species |

Features

|

Totals |

% of

Total |

% of

Each

Class |

| No. 70 | No. 71 | No. 72 | No. 75 |

|

| Identified Mammal | 7 | 20 |

50 | 2 | 79 |

6.7 |

|

| Unidentifiable Mammal | 59 | 158 |

156 | 75 | 448 |

38.1 |

|

|

| Total Mammal | 66 |

178 | 206 |

77 | 527 |

| 44.8 |

|

| Identified Bird | 53 |

29 | 82 |

28 | 192 |

16.3 |

|

| Unidentifiable Bird | 11 |

8 | 19 |

5 | 43 |

3.7 |

|

|

| Total Bird | 64 |

37 | 101 |

33 | 235 |

| 20.0 |

|

| Identified Fish | 14 |

19 | 9 |

5 | 47 |

4.0 |

|

| Unidentifiable Fish | 199 |

45 | 103 |

20 | 367 |

31.2 |

|

|

| Total Fish | 213 |

64 | 112 |

25 | 414 |

| 35.2 |

|

| Total Bone | 343 |

279 | 419 |

135 | 1176 |

100.0 | 100.0 |

|

| % of Total | 29.2 |

23.7 | 35.6 |

11.8 |

|

|

|

|

| British |

|

| Species |

Features

|

Totals |

% of

Total |

% of

Each

Class |

| No. 206 | No. 212 | No. 213 | No. 215 | No. 216 |

|

| Identified Mammal | 16 | 57 |

14 | 13 |

49 | 149 |

14.5 |

|

| Unidentifiable Mammal | 37 | 243 |

60 | 15 |

142 | 497 |

48.2 |

|

|

| Total Mammal | 53 | 300 |

74 | 28 |

191 | 646 |

| 62.7 |

|

| Identified Bird | 23 | 145 |

4 | 2 |

10 | 184 |

17.8 |

|

| Unidentifiable Bird | 8 | 89 |

1 |

|

5 | 103 |

10.0 |

|

|

| Total Bird | 31 | 234 |

5 | 2 |

15 | 287 |

| 27.8 |

|

| Identified Fish | 2 | 25 |

|

|

3 | 30 |

2.9 |

|

| Unidentifiable Fish | 1 | 58 |

4 |

|

5 | 68 |

6.6 |

|

|

| Total Fish | 3 | 83 |

4 |

|

8 | 98 |

| 9.5 |

|

| Total Bone | 87 | 617 |

83 | 30 |

214 | 1031 |

100.0 | 100.0 |

|

| % of Total | 8.4 | 59.8 |

8.1 | 2.9 |

20.8 |

|

|

|

|

| Mammal |

Bird |

Fish |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| French | 44.8% |

20.0% | 35.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| British | 62.7% |

27.8% | 9.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2: Species Identified From French Period Features

|

| Species |

Features

|

Total

Identified

Bones |

% of

Total

Identified

Bone |

Minimum

Number of

Individuals |

| No. 70 |

No. 71 |

No. 72 |

No. 75 |

|

| Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

1 |

| Beaver (Castor canadensis) |

6 |

11 |

28 |

|

45 |

14.2 |

7 |

| Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Black Bear (Ursus americanus) |

|

2 |

3 |

|

5 |

1.6 |

2 |

| Marten (Martes americana) |

|

|

3 |

|

3 |

.9 |

1 |

| Cervidae |

|

|

4 |

|

4 |

1.3 |

|

| Moose (Alces alces) |

|

2 |

4 |

|

6 |

1.9 |

2 |

| Pig (Sus scrofa) |

1 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

12 |

3.8 |

5 |

| Dog (Canis familiaris) |

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

.6 |

1 |

| Pied-Billed Grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) |

|

|

|

3 |

3 |

.9 |

1 |

| Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) |

|

1 |

|

1 |

2 |

.6 |

2 |

| Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) |

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

.6 |

1 |

| Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) |

2 |

|

|

4 |

6 |

1.9 |

3 |

| Green-Winged Teal (Anas carolinensis) |

|

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

.9 |

2 |

| Blue-Winged Teal (Anas discors) |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) |

|

|

2 |

1 |

3 |

.9 |

2 |

| Redhead Duck (Aythya americana) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

5 |

1.6 |

4 |

| Ring-Necked Duck (Aythya affinis) |

|

1 |

2 |

|

3 |

.9 |

2 |

| Lesser Scaup (Aythya collaris) |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Aythya sp. |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

.3 |

|

| Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) |

|

|

3 |

|

3 |

.9 |

1 |

| Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Common Merganser (Mergus merganser) |

|

|

2 |

|

2 |

.6 |

1 |

| Red-Breasted Merganser (Mergus merganser) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

.6 |

2 |

| Anseriformes |

1 |

|

5 |

2 |

8 |

2.5 |

|

| Goshawk (Acipiter gentilis) |

|

2 |

|

2 |

4 |

1.3 |

2 |

| Cooper's Hawk (Accipiter cooperii) |

|

|

2 |

|

2 |

.9 |

1 |

| Rutted Grouse (Bonsa umbellus) |

2 |

|

5 |

|

7 |

2.2 |

2 |

| Black-Bellied Plover (Squatarola squatarola) |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Ring-Billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) |

43 |

18 |

55 |

8 |

124 |

39.1 |

21 |

| Raven (Corvus corax) |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) |

1 |

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

1.6 |

4 |

| Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) |

4 |

17 |

3 |

3 |

27 |

8.5 |

4 |

| Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush) |

5 |

|

6 |

2 |

13 |

4.1 |

6 |

| Lake Whitefish (Coregonus sp.) |

4 |

1 |

|

|

5 |

1.6 |

3 |

| Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Burbot (Lota lota) |

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Total |

74 |

67 |

141 |

35 |

317 |

|

94 |

|

Table 3: Species Identified from British Period Features

|

| Species |

Features

|

Total

Identified

Bones |

% of

Total

Identified

Bone |

Minimum

Number of

Individuals |

| No. 206 |

No. 212 |

No. 213 |

No. 215 |

No. 216 |

|

| Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

4 |

1.1 |

3 |

| Beaver (Castor canadensis) |

5 |

14 |

5 |

1 |

15 |

40 |

11.0 |

8 |

| Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) |

|

|

|

2 |

2 |

4 |

1.1 |

2 |

| Black Bear (Ursus americanus) |

|

4 |

|

|

1 |

5 |

1.4 |

2 |

| Cervidae |

|

|

|

|

2 |

2 |

.6 |

|

| Cow (Bos taurus) |

1 |

5 |

2 |

|

7 |

15 |

4.1 |

4 |

| Pig (Sus scrota) |

9 |

33 |

5 |

10 |

20 |

77 |

22.2 |

10 |

| Sheep (Ovis aries) |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Cat (Felis domestica) |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Common Loon (Gavia immer) |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

2 |

.6 |

1 |

| Double-Crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus) |

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Whistling Swan (Cygnus columbianus) |

|

|

|

|

3 |

3 |

.8 |

1 |

| Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) |

2 |

4 |

|

|

|

6 |

1.7 |

2 |

| Redhead Duck (Aythya americana) |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Ringneck Duck (Aythya collaris) |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

3 |

.8 |

2 |

| Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

.6 |

1 |

| American Merganser (Mergus merganser) |

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Anseriformes |

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

.6 |

| Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

.6 |

2 |

| Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) |

10 |

131 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

148 |

40.8 |

22 |

| Bluejay (Cyanocitta cristata) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Raven (Corvus corax) |

5 |

2 |

|

|

|

7 |

1.9 |

| Domestic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

.6 |

2 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) |

1 |

12 |

|

|

2 |

15 |

4.1 |

6 |

| Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush) |

1 |

7 |

|

|

1 |

9 |

2.5 |

2 |

| Whitefish (Coregonus sp.) |

|

5 |

|

|

|

5 |

1.4 |

1 |

| Walleye (Stizostedion vitreum) |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

.3 |

1 |

| Total |

41 |

227 |

18 |

15 |

62 |

363 |

|

|

|

All but one of the species identified from the bones

in Fort Michilimackinac refuse pits have been reported from the Straits

of Mackinac area within quite recent times. Only the redhead duck

(Aythya americana) no longer occurs in the Upper Great Lakes

region. This species does, however, occasionally breed as far south as

southeastern Michigan and Wisconsin (Peterson 1958). The great frequency

with which the bones of this duck appear in the refuse pits at Fort

Michilimackinac seems to indicate that it formerly had a much wider

range. The retraction in the range of the redhead is no doubt due

primarily to modern hunting pressure.

The occurrence of one fish, the burbot (Lota

lota), seems worthy of comment since its presence indicates

something of a fishing technique employed by the French. In the Upper

Great Lakes the burbot occurs only in deep cold water (Hubbs and Lagler

1958). Since the aboriginal fishery of the Straits was basically a

shallow water harpoon and net fishery (Cleland 1966), the burbot was

probably caught by the French fishing in deep water with iron hooks like

those from Fort Michilimackinac.

Feature No. 212, a refuse pit in a British basement,

contained a cowrie shell (Cypraea moneta), a marine mollusc

native to the Indian and Pacific oceans. The "money cowrie," as this

species is commonly called, was a widely used trade item and has been

frequently reported from many areas of the world where it does not occur

as a native species (Jackson 1917). A good example was the use of this

cowrie by the Ojibwa as part of the ritual paraphernalia of the Grand

Medicine Society. Ojibwa tradition relates that these shells were given

to the Ojibwa by their folk hero Mi'nabo'zho (Hoffman 1891). A less

colourful but more plausible origin is the Hudson's Bay Company, which

used great quantities of these shells in trade for fur. The Fort

Michilimackinac specimen is presumably a discarded trade item.

Three quite different methods can be used to

demonstrate quantitative differences between the French and British bone

samples. These are frequency of species represented by bone count,

frequency of individual animals representing each species and the amount

of meat provided by each species.

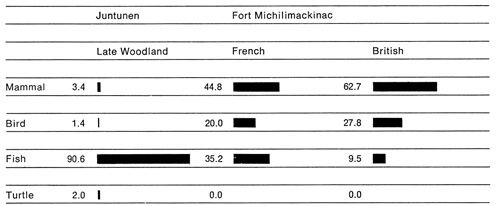

Figure 1 is a graphic illustration of the most common

method used in analysing faunal remains from archaeological sites, the

frequency of bones representing particular classes of animals. This

figure indicates that the French killed fewer mammals and birds than the

British, but that they caught more fish. Sheer numbers of bones,

therefore, seem to indicate that fish were a much more important source

of food during the French period than during the British period and that

conversely, mammals became more important in the latter period than they

were when the French occupied the site.

1 Comparison of Percentages of Total Numbers of Bones

|

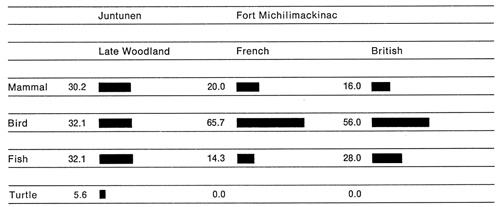

One may also compare the variety of species exploited

by the occupants of Michilimackinac during these periods. Referring

again to Tables 2 and 3, we see that although the French sample was

smaller than the British in terms of numbers of bones, the French sample

was larger in the number of individuals as well as the variety of

species represented. Thus, the French were exploiting a wider variety of

animal resources.

Figure 2 is an illustration of the percentages of the

kinds of species representing each class of food species. This figure

indicates that both the French and British seem to have been exploiting

a wide variety of birds. The French, however, were killing

proportionately more kinds of mammals, while the British were catching a

greater variety of fish.

2 Comparison of Percentages of Numbers of Species Represented by Bone

Refuse

|

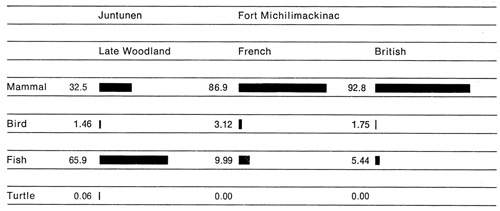

A third and more meaningful method of comparing the

food remains of these occupations is in terms of the amount of meat

which would be provided by the animals represented by the bone refuse.

This method has the advantage of balancing out the bias which arises as

the result of different bone frequencies and body weights of animals

used for food. White (1953) developed a technique for making such

calculations. His method consists of the multiplication of the pounds of

usable meat obtainable from an average sized individual of a particular

species by the minimum number of individuals of that species which are

represented in the bone refuse. The use of White's technique, with some

minor modification, resulted in the construction of Figure 3 (see

also Appendices A, B, and C). Here we see that meat derived from

mammals comprised the substantial part of meat consumed by both French

and British. Birds and fish, on the other hand, actually contributed

very little meat to the diet of either group. This point is, of course,

extremely important and it would have been overlooked had only a simple

bone count and/or a species list been used as the method of analysis.

Aside from the information which would have been lost by using bone

counts alone, it is very possible that the use of this method would have

generated erroneous conclusions concerning the relative importance of

animal species represented at Fort Michilimackinac. By using bone count

alone, one would be forced to conclude that fish were an important

source of food during the French occupation when in fact fish

contributed less than ten per cent of all animal food. Similarly, if we

used species counts alone, it would have been reasonable to conclude

that birds were a primary factor in the subsistence systems of Fort

Michilimackinac; in fact, fowl contributed less than four per cent of

the meat acquired by the French and two per cent of the meat obtained by

the British.

3 Comparison of Percentages of Pounds of Meat Estimated from Bone Refuse

|

This criticism is not meant to imply that counting

the number of species of birds represented in an archaeological site is

not a useful piece of information. Such a figure may be indicative of

rather important subsistence practices. Even though calculations based

on pounds of meat may be the most meaningful for discussion of the

over-all subsistence system, such figures are subject to

misinterpretation. We must always remember that these calculations give

no weight to other non-animal foods in the total diet. Presumably plant

foods constituted the dietary staple in most Late Woodland and historic

sites.

Before discussing the cultural variables which must

have been largely responsible for the differences in the kinds of

species utilized by the occupants of Fort Michilimackinac, it is

necessary to present a more detailed accounting of the importance of

various food species within the broad classes thus far discussed. Table

4 shows the proportion of meat derived from animals of various game

categories. We have already observed that mammals provided 86.9 and 92.8

per cent of the meat from French and British occupations, respectively.

Within this important food class, Table 4 shows that the amount of small

game used by the French was of about the same proportion as the amount

used by the British. Moreover, it is apparent that the French utilized

much more big game than the British, who in turn used substantially more

domestic animal foods than the French. Although fowl was never an

important food source, it is interesting to note that the quantities of

meat produced from various categories of wild fowl were consistently

greater during the French period. The same statement may be made about

the use of fish.

Table 4: Per Cent of Pounds of Meat Provided by Various Classes of Animals

|

| Juntunen

|

Fort Michilimackinac

|

| Late Woodland

|

French

|

British

|

| pounds | per cent |

pounds | per cent |

pounds | per cent |

|

| Domestic Mammals |

|

|

857.5 |

32.12 |

3,755 |

78.35 |

| Big Game |

4,962.5 | 22.93 |

1,220 |

45.70 |

420 |

8.76 |

| Small Game |

1,615.25 | 7.46 |

226.8 |

8.49 |

272.3 |

5.68 |

| All Other Mammals |

465.0 | 2.14 |

15.0 |

.56 |

|

|

| Aquatic Birds |

114.8 | .53 |

53.34 |

1.99 |

37.4 |

.78 |

| Upland Game Birds |

73.4 | .33 |

19.1 |

.71 |

19.8 |

.41 |

| Predatory Birds |

101.15 | .46 |

6.3 |

.23 |

|

|

| Domestic Birds |

|

|

2.24 |

.08 |

21.44 |

.44 |

| All Other Birds |

27.8 | .12 |

2.4 |

.08 |

5.4 |

.11 |

| Turtles |

13.6 | .06 |

|

|

|

|

| Sturgeon |

12,600 | 58.23 |

144 |

5.39 |

216 |

4.50 |

| Whitefish |

1,237 | 5.71 |

31.2 |

1.16 |

10.4 |

.21 |

| Lake Trout |

345.6 | 1.59 |

86.4 |

3.23 |

28.8 |

.60 |

| All Other Fish |

82.44 | .38 |

5.2 |

.19 |

5.6 |

.11 |

| Total |

21,638.28 | 99.94 |

2,669.48 |

99.93 |

4,792.14 |

99.95 |

|

|