|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 21

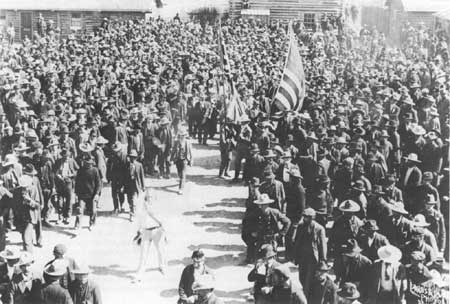

by Edward F. Bush The Klondike, 1886-99The first important gold strike, made in the winter of 1886-87, [1] determined the immediate future of the Klondike. With increasing popular interest in the Yukon evident, the Canadian government began to establish Canadian jurisdiction over the area: in 1895, surveys of the area were commissioned, a detachment of the North-West Mounted Police despatched to the Yukon, and the Yukon declared a district of the Northwest Territories. Two years later the land between the 141st meridian and the Liard River, and north of the 60th parallel was designated Yukon Territory and a territorial commissioner, a gold commissioner and a chief magistrate appointed. By the summer of 1897 the population of Dawson had swelled to an estimated 5,000, most of whom were aliens, largely Americans. News of the Carmac strike reached San Francisco and Seattle that summer and was given such publicity that the population of Dawson quintupled within two years. In the summer of 1898 the gold rush was in full spate, though ironically most of the valuable ground had been staked out the previous season. In those 20-hour-long, hot summer days with a three- to four-hour bright twilight between sun and sun, Dawson must have presented a fascinating sight to those new arrivals not too exhausted or penniless to appreciate it. They beheld a sprawling shack and tent town with a wide, dusty main street, frame shops, cafes, hotels and mushrooming brokerage and insurance offices, many with the false fronts so much a feature of town architecture in the late 19th century. With neither street names nor numbering, addresses could only be designated vaguely; many new arrivals spent days searching for lost partners. Despite the surveillance of the North-West Mounted Police, Dawson was a "wide-open" mining town in which bars, gambling rooms and dance halls prospered (though with the fantastic prices prevailing that summer and in some measure through the summer of 1899 as well, one wonders who could afford to patronize them). A jeweller's advertisement reflects the spirit of the summer of 1898: "Daylight all the time. The only thing that will save you from too much dissipation is Correct Time. Have your watches repaired by E. Merman." [2]

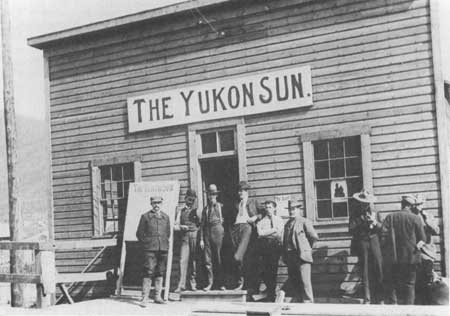

Dawson's Pioneer Press Clearly so thriving a community called for a newspaper and in June 1898 not one but two, publishing weekly, were forthcoming. The two argued subsequently which could rightfully claim to be Dawson's first newspaper. On the basis of the very first issue, according to Pierre Berton, the distinction belongs to the Klondike Nugget, whose enterprising editor, George M. Allen, borrowed a typewriter to produce his first edition on 27 May 1898 [3] although admittedly this would hardly pass as a newspaper, even by small-town standards. The Yukon Midnight Sun, whose editor and proprietor was G.B. Swinehart, came out with the first issue from a proper printing press, a diminutive quarter-size, eight-page edition, on 11 June 1898. The annual subscription was $15, "invariably in advance," and 50 cents per copy. As might be expected, mining and local items formed the early fare of these pioneer newspapers, particularly before the days of the government telegraph line to the outside, but the first issue of the Sun did include brief items on the Spanish-American War and an Anglo-French dispute in West Africa. [4] The Sun's edition of 20 June retained the same quarter-size dimensions, but increased to a dozen pages and by 18 July the paper appeared in the size and format it was to retain — four pages 17-1/2 inches by 23 inches, seven columns to the paper. The opening editorial announced: It is with no small pleasure that with this issue of the Yukon Midnight Sun we see fulfilled our repeated promises to furnish the people of Dawson a weekly newspaper . . . . The Yukon Midnight Sun will be a clean, bright sheet, free from domination by any class, clique or organization. It will be conscientious in the effort to be reliable on all subjects at all times: reflect the social and business life of the city and be an intelligent exponent of the great mining and other valuable interests of the Yukon valley. [5] In an issue a month later the editor assured his readers that he would give them a paper offering value for the money, rather than charging what the traffic would bear in the inflated conditions of a gold rush. This same issue, 18 July 1898, stated that their plant had been shipped from a West-Coast American port (probably Seattle) to Saint Michael, at the mouth of the Yukon, the year before. There it had had to be stored for the winter due to the lateness of the season while they used a light makeshift printing plant that had been packed in over the passes and thence down the Yukon by steamer. The permanent plant arrived on the steamer John J. Healey from Saint Michael on 9 July 1898, probably accounting for the greatly enhanced appearance of the paper, expanded to its full size, by 18 July. [6] As a service to the miners, the Sun offered a Guide to Dawson and the Yukon Mining District, to be available by 10 August and to include such useful information as mining regulations for both Yukon and Alaska, dominion land and timber regulations, descriptions of mining districts, tables of weights for gold dust, and a business directory. This was the first of a number of public service features produced by the newspapers of Dawson. The Klondike Nugget, managed by Zachary Hickman and Eugene C. Allen with George M. Allen and A.F. George as editors, began its stormy career as a mere typewritten sheet posted on a bulletin board in May 1898; the first printed paper was issued on 16 June. It became a semi-weekly after publication of its third issue. The original plant, described as a "small army press (200 lb.)," left Seattle in February 1898 together with one ton of paper and reached Dawson by scow from the head of navigation on 10 June 1898. [7] Like its contemporary, the Nugget was a four-page issue, 11 inches by 17 inches. Its annual subscription was $16. Its opening editorial began; Good Morning, Gentlemen The outside world is anxious for authentic information concerning the Klondike gold districts. The miners and other residents of this region are equally desirous of learning what is going on outside, as welt as of home occurrences. Hence the publication of the Klondike Nugget. We have no higher ambition than to satisfy our readers. [8] Under the heading,"The North and the Unsuccessful Gold Digger," the Nugget also commented on the ambitions of the gold seekers; if this rush were like others, not one man in a hundred would strike it rich; however, in the future, resources other than gold would support the territory and "no one may be expected to play a more important part than the man who came expecting to find gold and was disappointed." [9] The Sun welcomed the Nugget, expressing the perhaps facetious hope that "pleasant relations may always subsist [sic] among the fraternity in Dawson." [10] It did not take long for both editors and readers to be disabused of this notion for Dawson journalism, as was common in newspapers of the last century, was characterized by outspokenness and frequently descended to scurrilous abuse. The Nugget early saw itself as the champion of an oppressed citizenry, 80 per cent of who were American, against profiteering Canadian officialdom. It adopted a scathing roughshod style in which issues were seen in black-and-white terms. On the other hand, the Sun, though comparably ruthless in penning pugnacious leaders, evolved as the defender of the government while still pressing for reasonable reform. A wild free-for-all competition soon developed in which staff and readers of both papers enthusiastically joined. Berton describes the 67-year-old newsboy,"Uncle Andy" Young, tearing along the wooden duckboards which served Dawson as pavement, hawking the latest issue of the Nugget; "The Nugget! The Nugget! The dear little Nugget!" and disposing of a thousand copies in the course of an evening. [11]

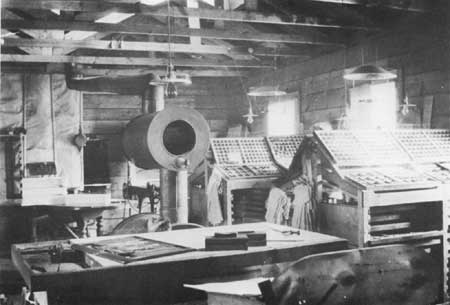

The personal columns of the two papers reflected the activity of the frontier as well as the gossip of the small town. From the Yukon Midnight Sun of 27 June 1898, the following items recall the activity of that summer. Edward Marks of St. Paul, a recent arrival has a position behind the Monte Carlo bar. Jas. Schneider of St. Louis and C.R. Boughton of Los Angeles came in Friday. They were among the few who made the trip successfully on a small raft. Leon Brock, of Buffalo, N.Y., one of the fortunates who escaped death after burial in the Chilkoot avalanche, is a recent arrival. He is a correspondent for the Buffalo Daily and Sunday Times. Ellis Lewis, half owner of No. 23 on Eldorado, an old Alaskan and successful miner, having been ten years at the business, left yesterday on the Bella, for California. He intends to take life easy and will probably be seen in this country only at cleanup time. It is hinted that he carried out about fifty thousand! Mr. Lewis is but one among many who, similarly fixed, left on the Bella, Weare and Hamilton. [12] The personal column of the rival Nugget offered yet more colourful fare. Mose Warren, a Canadian who arrived some months ago, has gone out into Sulphur with three horseloads of grub and two men. He has acquired interests on [claims] 25 and 31 above discovery [the first claim on a creek] and will work both claims. Mr. Lueders, the clever violinist, is quite sick with the prevailing dysentery. On Sunday night he had great difficulty in conducting the concert, but brought it through successfully in spite of his weakness. Mr. and Mrs. Robert Cahill have departed for their home in Portland. The sweet voice of Mrs. Cahill has beautified many a church service and lent pleasure to many a social evening and it is with regret we see the pair depart. Among the passengers on the steamer Columbian were Messrs. W.H. Miller, David W. Jones, Wm. Neville and Jacob Edholm. The two first named brought with them a large shipment of liquors amounting to in all 3000 gallons. They have secured a cabin on First Avenue, and for the present leave their goods in storage. [13] The Nugget's edition of 24 September 1898 graphically describes the mire on Front Street, of such a depth and consistency that many wagons overturned in the efforts to extricate them and often several teams could be seen struggling ineffectually in the morass. The Nugget also attacked the gold commissioner, a favourite target in its columns, observing that he had advertised for wood and that it was to be hoped that he would arrange to have it cut into stove lengths so that the line of waiting men at his office door will not have to suffer in the bleak cold while the muscular gold commissioner cuts his own wood, as happened last winter. Not but what the gold commissioner is a much better wood chopper than official head of his own office. [14] Through the summer and fall of 1898 both papers featured for the most part local and territorial news with some items from neighbouring Alaska, but by early July the issue of nationalism became apparent. During the gold-rush era Dawson was predominantly American with perhaps four in five of its populace hailing from the United States or Alaska. Located about 50 miles east of the international boundary on the 141st meridian, Dawson undoubtedly was in Canadian territory although at that date the boundary had yet to be fixed by joint survey and agreement. It is perhaps not surprising that many Americans on the outside were unaware that the Klondike was not part of Alaska; indeed, some Canadian newspapers fostered this misconception by referring to the Klondike product as "Alaskan gold." The American-owned Nugget naturally developed an American orientation, particularly as an opposition organ to the territorial government. The Sun, on the other hand, under the aegis of its first editor, Henry J. Woodside, an Ontarian of ultra-imperialist caste, and as the government organ, developed a strongly nationalist and anti-American bias. The Sun's Canadian orientation developed quickly: in its 4 July 1898 edition it ignored the American holiday completely while devoting a page to the celebration of Dominion Day. On 5 July the Nugget displayed its American sentiment in an editorial concerning the one-sided Spanish American War, including a generalization about the American Revolution. The Americans have demonstrated one thing to a great certainty, i.e., that they are nothing if not fighters, and more than this, that they can always produce the man for the emergency. All their wars have shown this. The war of the rebellion was the hottest in history, because between two factions of the same people and race; but now 'tis the whole people against a foreign foe, and the result can be well guessed as being the complete and full humiliation of haughty Spain. [15] The excerpt is also typical of the chauvinism found in all the Dawson papers — the English-speaking peoples were held to be manifestly superior to all others in both war and peace — however, this was not peculiar to the Klondike during the twilight years of the "white man's burden" and colonial empire.

The rival papers displayed a significant contrast in their attitudes toward the administration of justice and specifically the scaffold. Both agreed that hanging was proper punishment for a murderer, but the Nugget gloated over the mechanics and minutiae of execution whereas the Sun reported hangings in a more restrained and less detailed fashion. The Sun contrasted the swift efficacy of British justice with the endless appeals and procrastination of the American system. In the case of four Indians sentenced to death in July 1898 for murder, the Sun favoured commutation of the sentence in consideration of the fact that the Indians were alien to the ways of white society. Contrast this attitude with the following from the Nugget; The Treacherous Instincts of the Aborigines In a remote community in which typhoid was rife, one subject on which the rival editors could agree was the need for sanitation. Most Dawsonites drew their water close inshore from the Yukon River. By early October the first hard frosts had checked the contagion, but another summer was coming when the population of the tent-and-shanty settlement would perhaps double. According to the Sun's editor, As you were your own pilots coming down the Yukon, so now must everyone be his own health officer and board of sanitation. Therefore inspect and clean up your own locality like men, or supinely like sheep, fester and die in your tents. [17] By the fall of 1898 both papers had taken up their political stance. Both sought representative government and reform of the mining regulations, but whereas the Sun made allowances for governmental shortcomings due to the remoteness of the region, the Nugget saw federal authority as the ruthless exploiter of the miner, on whom the whole economy of the region depended. At this period the Yukon council was wholly appointive. This was due in part to the high proportion of aliens in the territory and in part to the fact that the government was dealing with a transient population. The Nugget itself complained of the lack of community interest in a largely intinerant population, few of whom had any notion of staying in Dawson. Since few stampeders were Canadian, pressure had been exerted on the Ottawa authorities to ensure that the aliens would not be permitted to strip the territory of its wealth with no return to the dominion. Hence a royalty of ten per cent had been levied on all gold mined in the Yukon. Unlike many countries, including the United States, Canada permitted aliens to dig for gold, subject to the royalty and reservation of a portion of the claims to the crown. Yet even the pro-government Sun found the royalty a burden, not in principle but in application. "The excessive burden of the royalty tax has been a lodestone on the mining industry. The small extent of mining ground sufficiently rich to meet this tax is only found on the richest claims of Eldorado." [18] In contrast the Nugget declared itself adamantly opposed to both the royalty and crown reservations on the grounds that these hobbling and unjust regulations were based on totally misleading reports on the richness of the goldfields. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||