|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 21

by Edward F. Bush The Klondike, 1886-99(continued)The Fawcett Issue The prime grievance that summer of 1898, and an issue not resolved until the following spring, was the alleged malfeasance of Thomas Fawcett, the gold commissioner. He was held by the Nugget to have favoured certain claimants and conducted his office with utter incompetence. (The gold commissioner's office was inundated with a torrent of business which the staff was utterly incapable of coping with; men queued up throughout the night in order to be admitted to file their claims the next day.) On 27 August 1898 the Nugget accused Fawcett of illegalities in claims registration for the benefit of his friends. Fawcett resigned his office, but brought suit against the Nugget for libel. The commissioner, William Ogilvie, wrote to Sifton on 28 February 1899, making clear where the Nugget stood in his estimation. You will probably see a copy of the Nugget of last Saturday which treats of the affair in a most inflammatory and seditious way. This sheet is run by Americans, with an Englishman (E. C. Allen) for editor. It appears these people have never had any newspaper experience heretofore and have not learned that many of the stories they hear are simply eminations of frenzied individuals who imagine they have lost a fortune because they cannot get the claim they wish or some similar idea. [19] Despite the Nugget's withdrawal of its charges, Fawcett insisted on the case taking its course and was completely exonerated. Ogilvie was appointed a royal commissioner under letters patent of 7 October 1898 to investigate fully the operations of the gold commissioner's office. It transpired that Fawcett had closed the claims on Dominion Creek in November 1897 not for the benefit of his friends, but because conflicting claims made an investigation necessary. [20] It does not appear from subsequent issues that the Nugget accepted the verdict in a chastened mood; lawsuits were common in the Klondike. The Nugget persisted with notions derived from American mining camps in which camp meetings formed by elected miners served the function of legislature and court of justice combined. Since at this date the Yukon was not represented in Parliament, the Nugget proposed the despatch of a miners' delegation to the capital. This was never implemented even though the Yukon had to wait until 1902 for parliamentary representation. A third paper, a four-page seven-column journal which began publication probably in September 1898, was known as the Klondike Miner and Yukon Advertiser and was originally under the managership of W.V. Sommerville with C.A. Walsh as editor. The earliest issue available is that of 16 December 1898. As its title indicates, this paper catered to the mining community and concerned itself mainly with local and territorial news. In contrast to the Sun and Nugget, the Klondike Miner displayed considerable advertising matter on its front page, though not to the exclusion of news. The Miner may be considered more of a tradesman's journal than the other two, though all three claimed to be the self-appointed champions of the miners. The 30 December 1898 issue of the Miner contains an editorial indicative of Dawson society of the time. A dance-hall manager apparently had requested a visiting celebrity, a well-known actress, to leave the premises because of the disreputable character of the dance-hall girls employed there. The visitor complied, but the editor held forth on the condition of society in the mining town with its few virtuous and respectable women, and he concluded in histrionic style on the inevitable depravity of such a society, stating "Dawson society is an odoriferous stench." [21] As their first season drew to a close the rival journalists sharpened their pens. G.B. Swinehart, publisher of the Sun, drew the fire of the Nugget with the allegation that the Nugget was in financial difficulties. On 30 November, not scrupling to make game of the rival publisher's name, the Nugget delivered the following riposte: We would have been pleased to allow Swinehart to sink into obscurity without attention being called to that fact. But Swinehart, and the name peculiarly fits the man, could not yield the ghost without endeavoring to vent the spleen which a defeated and routed opponent always feels towards a successful rival . . . . The Nugget has succeeded where the Sun has failed; and long after the latter has set forever the Nugget will be in the field doing business at the old stand and championing the cause of the people against every enemy whether it be in the shape of a misfit official or a twopenny newspaper whose editorial columns are the beck and call of every man who responds to a request to open his purse strings. [22] It was the Sun, however, which displayed greater staying power than the Nugget, albeit as a satellite of the redoubtable News. Berton asserts in Klondike that paper became in such short supply in the hard winter of 1898-99 in Dawson that the Nugget was printed for a time on butcher's wrapping paper. [23] This may be so, but is not apparent from the microfilm copies available in Ottawa nor was reference found to it in either paper. Early in 1899 the Nugget boasted that its circulation had risen from an initial 350 to 1,992. Unfortunately, research to date has not uncovered a corresponding statement for the Sun. Through February and March, issues of the Miner and the Nugget gave evidence of printing a little more international news; the Miner's edition of 10 March 1899 included on its front page a despatch from the Philippines and a description of the Omdurman engagement, as well as an article on the queen's grandson, Prince Alfred. The same paper performed a notable service to the largely alien population on the creeks by printing a three-column editorial explaining the basic principles of the Canadian constitution, concluding with a defence of the much-maligned Fawcett. Certainly some measure of the discontent felt in the Yukon was based on ignorance of Canadian practice or the assumption that it resembled American. On 19 May the Miner administered a well-merited rebuke to irresponsible journalists who engaged in continuous abuse of public officials: "The freedom of the press is a great blessing, the license of the press is a great curse to the community when it is under the knavish direction of self-seeking men." [24] And on 14 July the editorial columns of the Klondike Miner responded to an anonymous attack on Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Steele, officer commanding the North-West Mounted Police Yukon detachment, published in the Seattle Times. Steele had allegedly behaved in an arrogant manner with an American citizen. The Miner defended Steele, referring to the anonymous originator of the yarn as a "drunken scoundrel." The Nugget had charged as early as 7 December 1898 that the Sun and the Miner had merged under one management. The Miner, alleged the Nugget, had based itself on defence of the common interest whereas the Sun had become an unabashed government hack; the two interests were surely incompatible. However, the subject was closed by the following summer; the Miner ceased publication in August 1899.

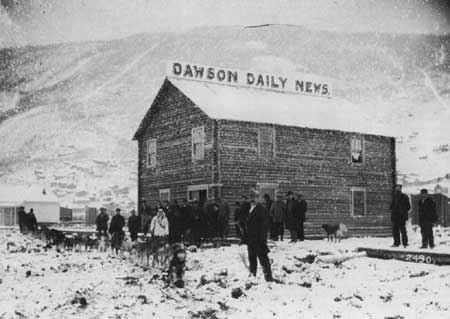

The Nugget and William Ogilvie The Nugget had at first welcomed William Ogilvie's appointment as commissioner, hoping for reform at his hands. In September 1898 the Nugget editor wrote that Ogilvie's appointment had done much to reassure the miners and that he could not be expected to correct overnight all the abuses perpetrated by his subordinates, there being only so many hours in the day, but by the following March the paper had lost patience with the commissioner. In its 23 March 1899 edition it had published an open letter from the chief executive in which he explained how he had disposed of personal land holdings on being appointed commissioner. The following week the Nugget editor, alleging some small discrepancy in the dates quoted by Ogilvie for the sale of his property, printed a mean-spirited, insinuating attack on the commissioner's integrity under the heading,"Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin." At one point, however, the Nugget doubled back upon itself: "The prevarication is really not of serious moment except as showing which way the wind blows." [25] In July 1899 the Nugget pronounced Ogilvie's tenure a disappointment "as he has done little but assist in saddling exactions upon the country which Sifton had." [26] In contrast, the Sun, under the editorship of Henry J. Woodside as of May 1899, on 23 May proclaimed its editorial policy; criticism of the government when facts warranted it, but avoidance of continuous fault-finding. Woodside, a native of Bruce County, Ontario, staunch Orangeman and ultra-royalist, was to editorialize trenchantly in the columns of the Sun, apart from a few months' leave of absence on volunteering for service in South Africa, for the better part of two years. Woodside had begun his career as a CPR telegrapher and had gained his first experience with journalism in Portage la Prairie. He had served with the Manitoba Grenadiers in the Northwest Rebellion and finally arrived in the Klondike in March 1898 as correspondent for the Manitoba Free Press and the Montreal Star. The obverse of Woodside's imperialism was a militant anti-Americanism, exacerbated by the American orientation of pioneer Dawson. Woodside considered the Americans in Dawson much too obstreperous, presumptuous, aggressive and numerous to be suffered quietly. He took it on himself, through the editorial columns of the Sun, to set the Americans straight, a policy which finally cost him his job. At the outset he seemed a good choice as editor of the government paper and might have continued in this office had he exercised a little prudence in the editorial chair. About the time Woodside joined the Sun staff, the paper's first office and plant was destroyed by fire; the 2 and 9 May issues were reduced to the old quarter-size with which it had begun, but by 16 May it had resumed its regular format. The Debut of the Dawson Daily News July 1899 saw the publication of a competitor that was to outlast both the Nugget and the Sun and to hold the field as Dawson's prime newspaper for nearly half a century. The Dawson Daily News first came from the press on 31 July 1899 and from the beginning outclassed its contemporaries. Initially numbering four 20-inch by 24-inch pages, the paper's format and quality classed it with the metropolitan dailies — which indeed it was. Like the Nugget, the News was to be an opponent of the administration, but apparently the former's owners did not foresee this, anticipating that the News would be a government supporter like the Sun. In its leader of 1 July 1899, the Nugget welcomed the newcomer. The Nugget extends the glad hand of fellowship to these gentlemen, and wishes to assure them that there is a wide and almost unoccupied field in Dawson for their activity. When the Daily News is installed and ready for business we hope to see the government's position supported and upheld with the energy and ability which the situation requires, and which we are aware the publishers of the News to be possessed. [27] Referring to the Nugget as the "yellow rag," the Sun commented that since the proprietors of the new paper were also Americans, they could not be expected to know much about the Canadian scene: hence their support would not be of much use to the government. As the first and for a time the only daily in the territory, the News took for its slogan,"The News When it is News." The paper came out every evening except Sunday, for 25 cents per copy or $35 per annum. The News also published a weekly edition, for an annual subscription of $10, directed at the mining population out on the creeks. Substantially the same news appeared in the weekly as in the daily edition. The News was founded as a joint venture by the New York-born Tacoma publisher, Richard Roediger, and his Canadian partner (from Simcoe, Ontario), William McIntyre. Roediger, who began life at sea (from which may have been derived his popular title of "Captain"), acquired extensive experience in the newspaper business in association with McIntyre, acquiring a large interest in the Tacoma News which he ran until 1898 when he left for the Klondike. McIntyre accompanied Roediger to Dawson to set up the plant, but thereafter the control of the paper rested entirely with Roediger. [28] W.A. Beddoe, an Englishman who was one of its later editors, was called by a rival "that Juneau blackguard," but such epithets were not to be taken too seriously in frontier journalism. at the turn of the century. The issue of Americanism was to become a sore point with all three Dawson papers. Of the trio, the Sun best merits the designation "Canadian," but there is little doubt which of the three was the best paper. The News led in typography and plant, editorial writing, news coverage and features though it was perhaps not quite a match for the vituperation in which the Nugget excelled. The first copy available, though not the first printed, of the Dawson Daily News, that of 5 August 1899, devoted one whole page to international news. From the outset the News took a broader view than its contemporaries although it gave ample evidence of its proclivities, particularly on Washington's Birthday and on the Fourth of July. Outspoken as it could be in the fashion of the time, because of its position in a predominantly American community within clearly designated Canadian territory, the News avoided the issue of Anglo-American relations. In 1899 the Alaskan boundary was already a contentious issue, involving Canadian access to the coast on the Lynn Canal within the Alaskan panhandle. As the News saw it, the United States and Great Britain were adopting a diplomatic and mature attitude over this matter, refusing to be stampeded by Canadian hotheads who talked of war.

We are certain that the United States does not want a war with Great Britain; we are even more positive that the latter power does not wish to exchange blows with the United States. In the meantime, it would be well to shelve this talk of a resort to the "arbitrament of arms", which comes from Ottawa. While it is a nice, high-sounding phrase calculated to stir the blood, it cannot be taken seriously at the present time. In fact it is the veriest rhodomontage. [29] But more cosmopolitan though its outlook was, the News devoted its main editorial energies to the same issues as the Nugget and the Sun; mining regulations and representative government. By mid-August the new paper had definitely aligned itself with the critics of government in the Yukon. Its first target was the ten per cent royalty which had been defended by the Vancouver World on the grounds that the Yukon cost Canada a great deal of money; the News contended that the revenues derived from the territory matched the parliamentary appropriations. Mining license fees were too high. The federal government was mulcting the territory when it should do everything to encourage the miners and hence to open the country up. In its issue of 11 September 1899, the News warned the government that the limit of endurance had been reached in the Klondike, that another year of neglect, excessive fees and restrictions would strangle the mining industry and drive the miners to fresh fields. Despite the intense competition for gold and the presence of so many nationalities in a remote region, the Klondike was considered a model mining camp in the sense that felonies were promptly punished. Brawling, drunkenness and prostitution were inseparable from the mining camp and the frontier, but the authority of the law was never challenged, let alone set at naught as had happened in Skagway and in some measure in most American mining camps. The exceptional quality of the North-West Mounted Police was acknowledged by all three papers. Yukon justice was speedy, but followed due process of law in the British tradition. It is interesting to note that the Dawson Daily News had the temerity to express doubts about the efficacy of capital punishment when society not only condoned it, but justified it as suitable retribution for those who had willfully taken life. The News nonetheless cited quite modern arguments against the practice: life imprisonment (with no qualification or possibility of parole) was surely a more fearful deterrent than the death penalty and with capital punishment there was no opportunity to redress a miscarriage of justice. At the same time this editorial was written in the first week of August 1899, the hanging for murder of one Robert Henderson and two Indian accomplices was in train. In reply to the News, the Sun on 15 August came out strongly for the continued employment of the hangman. We have no sympathy with the mawkish sentimentality that speaks of an execution as "judicial murder"! If there are extenuating circumstances, the man slayer is seldom hanged. In Canada we do not cultivate that love for the "dear criminal," which makes a hero of a brute murderer like Jesse James or the Younger brothers. We simply hang them as high as Hainan and have done with it. Therefore Canada is entirely free of that class of desperadoes. [30] At the execution of Henderson on 5 August, the Sun contented itself with a modest description of the proceedings. "Everything worked smoothly and most decently, without a hitch of any sort, but a glance at the scaffold and the drop gave evidence of a very careful arrangement and attention to the most minute details." [31] In contrast, the Nugget devoted the whole of its front page to the execution to the last grim detail, complete with a sketch of the final scene on the scaffold. It was Klondike's first hanging and the Nugget made the most of the occasion. Six weeks later the Nugget outdid itself, justifying the lynching in the southern states of Negroes accused of raping or molesting white women. [32] An incident occurred early in April 1899 involving the American consul, James McCook. It must have been an acute embarrassment to the American community, though affording much amusement, and was the sort of drunken vaudeville that occurred from time to time in frontier settlements all over the world. From the columns of the Nugget comes this report. Consul J.C. McCook, the American representative to the Yukon territory, constituting the buffoon of a dance hall crowd while in a state of intoxication, was a lamentable spectacle witnessed at the Phoenix on Thursday morning last . . . . Mr. McCook appeared at the Phoenix at a late hour in the morning, apparently under the influence of a heavy "jag". He was inclined to be merry and was evidently out for a good time; but above everything else was evidenced his dignity as the American consul. "Who isn't an American citizen?" was the form of his salutation, as he entered and gravitated gracefully toward the bar. A young man standing by assumed to believe that the inquiry required an answer, and he said he was not. "Then I'll make you one in two minutes," roared the consul, and he made a rush at the other. The two careened across the floor into a room occupied as a branch office by the Nugget Express, and were only saved from going through the window into the street by the timely exertions of Proprietor Pete McDonald. The men were separated and a treaty of peace was happily ratified over a round of drinks. The consul then endeavoured to show that his heart was in the right place by ordering a fresh round every time anybody declared him or herself to be an American — for by that time the girls had been attracted from the dance hall and had gathered about the celebrator. He could not, however, overlook or forgive the temerity of his late adversary who had presumed to declare his allegiance to the queen, and the additional drinks taken had put the consul in a state of utter recklessness. So it was not long before he again turned his attention to the young Canadian who stoutly refused to forswear his country, and the two were soon mixed up again. Their manoeuvres finally landed them in the dance hall, where they fell to the floor, with Pete the night porter — who was not sober himself, — on top of them. A couple of interested spectators took hold of the squirming men by the heels and dragged them into the barroom, where they were disentangled and again the bloody chasm was bridged with the flowing bowl. Mr. McDonald also attempted to restore order by suppressing the young man. The consul then turned his attention to lighter things than upholding the dignity and greatness of his country and, with one of the seductive damsels at his side, was soon participating in the merry maze. He made himself a strong favorite with all the girls and they are not easy to please, either — and he became the centre of their group. To again show that his heart was in the right place — and that he knows a pretty girl when he sees one — the gallant colonel unfastened his gold watch from its chain and formally presented it to Nellie James. This special mark of favor made the other girls envious and disgruntled, and in order to placate the beauties he proceeded to distribute among them a choice collection of gold nuggets which he had about his person. His unexpected generosity seemed to grow with the giving, for he suddenly threw up his hands and invited the girls to help themselves to anything they could find: "Take the whole works!" he exclaimed encouragingly. The girls couldn't withstand such eloquent and manly persuasion and they soon had the pockets of his coat, vest and pants turned inside out. The utmost jollity prevailed, and the good humor of the consul being exceedingly infectious and one of the party contributed to the humor of the occasion by pinning a small symbol of the Stars & Stripes to the rear of the consul's pants. It may have been this which inspired the consul with a most original idea for contributing further to the amusement of the crowd. Taking hold of the bar railing he bent forward until his coat-tails stuck out conspicuously, and then called "Kick me, Pete." This referred to the aforesaid night porter, who not wishing to disappoint the expectant throng, Pete several times planted the toe of his boot against the consul's posterior. The effect was so extremely delightful to the colonel that he urged Pete to still greater exertions, and being willing to oblige to the extent of his power, the porter would start on the run from the other side of the room and almost send the consul over the bar with the force of the impact between shoe leather and tweed worsted. Though it was nearing the breakfast hour, the throng, which gathered to witness the granting of the consul's desire to be kicked was large and scornful; but nothing could detract from his own enjoyment of the scene. Each succeeding impact was greeted by roars of coarse laughter from the colonel at the fact that breath was getting knocked out of the porter while his own remained intact and strong. Thus the time passed merrily until, exhausted with his own merriment, the jolly consul could stand no more, and he begged permission to retire. It was a difficult accomplishment alone, and two men — each holding an arm — accompanied him out the back door, past the row of bawdy houses down the alley to Second Street, where he was left to make his way as best he could to his room across the way. Genuine hardship here befell him for he met with a chilly rebuke from a girl whose "cigar store", standing at the corner of the alley, he attempted to enter, lost his equilibrium and fell to earth. He made several vain but heroic attempts to arise, but being unable to do so, he finally resigned himself to his fate and crawled on his hands and knees across the muddy alley upon the sidewalk to the door leading to his office building, which he entered. A score of people, standing in a group at the corner, were witnesses of this spectacle, but only the consul and his Maker, possibly, knew how the final journey up two flights of steep stairs to his room was accomplished. [33] In the same issue the Nugget entreated the consul to resign "before you further trail the glorious flag in the mire," but instead McCook sued the Nugget for libel. In court, however, witnesses verified the Nugget account and McCook left before judgement was rendered against him. The Nugget pursued its victim, demanding his recall, but predictably the harrassed consul found a defender in the rival Sun. Though he lost his lawsuit, McCook retained his post, his government less concerned by the consular indignity in remote Dawson than the Nugget. |

|||||||||

|

||||||||