|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 21

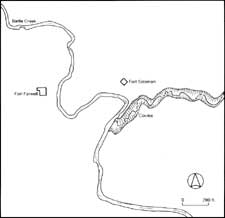

by Philip Goldring The SceneIn the centre of the Cypress Hills, a few miles east of the present boundary between Saskatchewan and Alberta and 40 miles north of the international boundary, the valley of what we now call Battle Creek cuts a trench through uneven terrain. At one point, a mile and one-half below the junction of Spring Creek with Battle Creek (where the Mounted Police set Fort Walsh to quell the whisky trade in 1875), the hills rise gently away from the water well back from the creek banks, the river turns sharply to the east and the valley widens slightly to take the shape of a bowl. This has two openings toward the north. The river is one and the other is a short, deep box canyon from which a coulee twists across gently sloping ground to join Battle Creek. A spring wells up in the hillside and empties into the creek 400 feet upstream from the mouth of the coulee. It is an impressive place, remarkably attractive even in the striking scenery of the Cypress Hills. This, a century ago, was the scene of the Cypress Hills massacre. In the fall of 1872 Abel Farwell arrived from Fort Benton and built his fort, a collection of palisaded huts, about 100 feet from the nearest point on the stream and 600 feet in a straight line from the point where the coulee joins the creek. Facing Farwell's fort in friendly rivalry was one built by Moses Soloman at about the same time. [1] Fort Soloman was square with bastions. The main building was L-shaped, with two walls of log palisade to fill out the complex into a square or rectangular shape. The lone gate could be locked against intruders by what the watchman later called "a log chain." [2] The fort was 150 feet roughly northwest of the nearest point on the coulee and 600 feet from Fort Farwell. The third feature of human habitation in the area was the Indian camp, a cluster of 40 or more lodges on rising ground south of the coulee. At no point was it closer than 42 feet from the coulee and it was probably at no point closer to the creek than about 50 feet. [3] It was therefore more than 600 feet from Fort Farwell, on the opposite side of the stream. For years the exact configuration of the massacre ground was in doubt and the reputed locations of the two forts and the Indian camp rested on the slim evidence of an old Métis who had herded cattle on the site seven or eight years after the massacre. Over 50 years later, he pointed out to interested individuals the site where he had once found human bones and that, it was decided, must be the campsite. This recollection of Jules Quesnelle was a useful indication, but by no means decisive. [4] The issue was left further in doubt when amateur archaeological efforts in the mid-1940s failed to turn up evidence of the body of Ed Legrace, who was known to have been buried under Fort Soloman. [5] In 1972 the National Historic Parks and Sites Branch began historical and archaeological research to find the exact locations of the two posts and the Indian camp. Documentary research failed to turn up a contemporary map of the massacre site (though one was drawn in 1875), [6] but did confirm that the traditionally ascribed location satisfied the measurements taken on the site by the Mounted Police in 1875. Part of the traditional story was given dramatic confirmation by the archaeological efforts by Jack Elliott on the supposed site of Fort Soloman. He discovered there a skeleton which appears to be that of an adult male, buried by whites. The grave provided no objective means of determining that the remains were definitely those of Legrace, [7] but the burial coincides with the supposed location of Legrace's grave. The region has a sparse history of white settlement and it is unlikely that another, unrecorded burial would have taken place at that spot. Elliott also found evidence of log structures dating from after 1850 under the site of Fort Farwell. Assuming, then, that the two trading posts have been correctly located, the documentary evidence makes it clear that the Indian camp stood on the south side of the coulee, east of the creek and far enough up the slope to be visible from both forts. Such was the scene of the Cypress Hills massacre. On the west side of the creek stood Fort Farwell; opposite were Soloman's post and the Indian camp. A fragile balance had been preserved between the whites and the successive bands of Indians who had occupied that encampment. Then, on the eve of Farwell's departure from the hills, the Benton party arrived. Their presence, their gross intemperance, would destroy everything. Before they left, death swept down the valley; all human habitation became smoking ruins. The passage of seasons and the flooding of Battle Creek soon erased all but a shadow of the forts and the campsite, but nothing has washed away the notoriety which the massacre of 1873 gave to the Cypress Hills. |

|||||||

|

||||||||