|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 18

The Construction and Occupation of the Barracks of the King's Bastion at Louisbourg

by Blaine Adams

Introduction

The barracks of the King's Bastion was part of the land defence

system which stretched across the mouth of the Louisbourg peninsula.

This defence consisted of two full bastions and two demibastions at

either extremity; the barracks spanned the gorge of the King's Bastion

and combined with it to serve as a citadel, a fort within the fortress,

from which a last stand could be made should the walls of the city be

breached. It was never tested in this regard for when a stand was

contemplated during the British siege of 1758, the citadel was in such

poor condition from enemy fire that the area around the Princess

Demi-bastion in the south end of town was the only area considered

defensible if the enemy assaulted.1

The barracks building was known by many names. In official

correspondence it was most often simply called the casernes

(barracks) or, in combination with the King's Bastion, the "citadel."

Sometimes the various parts of the building were referred to by name:

the officers' quarters, the chapel, the governor's (or government) wing

or soldiers' barracks. The terms fort and chateau were

used, though less frequently.2

The building sat on the highest point of land in the peninsula and

closed off the King's Bastion from the town. A dry moat added to its

isolation, and the only access to the building was over a drawbridge at

the centre which led to the terreplein or courtyard of the King's

Bastion and to the doors leading into the various rooms themselves.

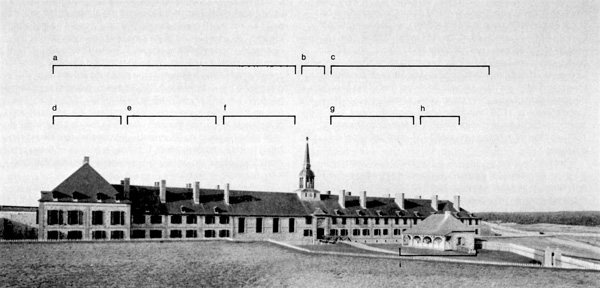

1 The reconstructed King's Bastion barracks. a, south half;

b, central passage, armoury and clock tower; c, north

half; d, governor's wing; e, officers' quarters; f,

chapel; g, guardrooms and soldiers' quarters; h, north

wing; i, guardhouse. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The concept of barracks as housing for the military was relatively

new to 18th-century France and its colonies, and the barracks

constructed in Louisbourg was one of the few in French North America.

The most common method of housing soldiers was billeting in private

homes, a method preferred by the soldiers who were thus away from the

control of their officers and could lord it over their hosts. To rid

themselves of the soldiers, the townspeople often raised money, usually

through a consumption tax, to build and maintain barracks for the

soldiers. The government rarely built barracks, but had begun the

practice of buying or renting empty houses for use as military

dwellings, and this remained the most common method for housing troops

in 18th-century France.3

The colonial troops were not part of the army but came under the

Département de la Marine and were referred to as Troupes de la

Marine or Compagnies Franches de la Marine as opposed to the

Troupes de la Terre of the army. The Département de la

Marine had been subject to various administrative reorganizations in

the 17th century and it was not until 1689 that a royal ordinance

finally established the organization and procedures to be followed in

this ministry. Another ordinance the following year dealt specifically

with the raising and discipline of soldiers on ships, and in 1695 rules

were issued for companies serving in Canada.4 Many aspects of

military life in the Marine were not covered by these decrees;

nevertheless, in 1720 officials at Louisbourg were rather haughtily

informed that the ordinance of 1689 foresaw everything and that it had

only to be read and applied to the letter. Ten years later officials

were told that, if the Marine ordinances did not apply, the

compilation of military regulations, the Code Militaire of 1728,

was to be used. In some cases, as in the questions of deaths and

inventories, the Marine ordinance of 1689 and the military

ordinance of 1731 were both applied to find a solution.5

Where no regulations applied, a pragmatic approach was adopted.

Barracks, for example, were not mentioned in the 1689 ordinance, in

which it was assumed that soldiers would be billeted in private homes.

Yet when the first Louisbourg settlers and soldiers arrived from

Newfoundland, which had been lost to France by the Treaty of Utrecht in

1713, no houses were available. A barracks was the obvious solution to

military housing, but there were no rules or specifications outlining

what should be included or how one should be built.6 The

first contract for works at Louisbourg was a nine-page document

outlining what was to be done,7 but a contract some 18 years

later had grown to 24 pages and was much more precise and

detailed.8 With few precedents to follow, officials had many

difficulties establishing procedures for the construction and occupation

of the main barracks in Louisbourg.

Of course, other factors contributed to problems with the barracks

during its construction. Despite optimistic first indications, local

building materials were not readily available. The first engineer at

Louisbourg reported with characteristic overstatement, but also with

some element of truth, that firewood was more expensive than the best

French wood.9 Difficulties were encountered with masonry:

unless the sand was thoroughly washed, the salt from the sea water acted

as a corrosive in walls exposed to the weather, and the mortar failed to

act as a proper binding agent. Other building materials, slate, stone

and brick, were of poor quality or in short supply.

There was also the problem of the short construction season. The

chief engineer reported that there were seven months of snow or harsh

weather leaving only five months in which building could be carried on.

Omitting Sundays and holidays and at least 20 stormy days, this left, he

calculated, only 93 days in the year during which there could be

effective construction.10

There were constant difficulties in obtaining qualified and competent

craftsmen. Engineers spoke of the carelessness, laziness and indolence

of workers paid by the day,11 and a new contractor, in 1726,

complained of the lack of skilled workmen for the elaborate woodwork in

the chapel.12 There were laments that the men who came to

Louisbourg were not good physical specimens.13 Little is

known of the average workers' age, but in a group of 40 new arrivals in

1726, who were referred to as being a good lot, the majority were 15 to

16 years old.14 Drunkenness among the workers was a constant

problem; the governor once complained that when the men were paid they

left their work in spite of all he could do. Numerous ordinances were

issued regulating taverns and their hours,15 but the

repetition of these prohibitions throughout the history of Louisbourg

indicates that they were not easily enforceable.

Finally, work on the barracks was hampered by conflicts among the

senior officials of the colony. In the early years at Louisbourg there

was more than the usual amount of bitterness in relationships between

the military administrators and the builders. The leading officials of

the colony were the governor, who was the principal military officer,

and the commissaire ordonnateur (often simply called the

ordonnateur), the chief civil and financial officer. Both

reported individually to the ministry of marine in France, and, on

matters of mutual concern, wrote joint reports. Without a clear

delineation of functions, quarrels were inevitable, especially with

regard to the barracks which was within the jurisdiction of both

officials. To complicate matters, the chief engineer was in frequent

opposition to one or both officials. The chief engineer's function was

to draw up plans and supervise construction. He was a member of the

engineering corps, a separate department whose members were attached to

military units where needed. Being more familiar with land forces, the

first engineer was criticized for not doing things the Marine

way. In an effort to mitigate this difficulty a special memorandum

describing work procedures was prepared in consultation with all

parties.16 Most of the officials in Louisbourg were of the

nobility, some from established families (d'épée) and others from

recently ennobled ones (de plume); a Mémoire du Roy of

1718, probably issued in reaction to reports of friction, urged both

groups to get along for the good of the service.17 Also

involved in the construction was the contractor who arranged for

materials, provided some of the workmen, and had to have his work

approved by the other officials before he received his money.

Before considering the construction and occupation of the building,

some discussion of the building practices is necessary. At the start of

each major undertaking, the ministry of marine, in a document called the

Devis et Condition, outlined in general terms the kind and extent

of work to be done and specified the standard of work expected and

quality of materials to be used.18 The contractor then

submitted a bid listing his unit price for each item in the

construction. The bid for a fireplace, for example, would not give a

total estimate for the finished product, but rather would quote a price

per cubic foot of masonry. The contractor would then be paid that unit

price times whatever cubic measurement the engineer or his assistants

calculated for the feature. Labour was not a factor in these contracts,

and the contractor had to ensure that his quoted price covered this

expense. In some cases, as in masonry wall construction, the contractor

was paid for the entire wall even though there were openings for doors

and windows which did not contain masonry. The extra payment in this

case was to compensate for the labour involved in fashioning these

features. Similarly, chimney stacks were considered to be full blocks of

masonry to compensate for the labour it took to make the flues.

Transportation of materials in the first Louisbourg contract was at

royal expense though this was modified in later

contracts.19

The ministry then told the officials on the site how work was to

proceed. In a memorandum in the summer of 1718 it was stated that

nothing was to be done without orders or approval from

France.20 Once work was approved, the estimates were to be

prepared by the ordonnateur from the work orders submitted by the

engineer and were to be calculated in his presence as well as that of

the governor. At the end of each year, the engineer was to prepare for

the ordonnateur and the governor an account of work done that

year. This account would be forwarded for payment minus the sums the

contractor had already been paid. The engineer was to be given every

assistance, including the troops and officers he required. The

contractor would pay the troops according to a scale worked out between

them. If an agreement could not be reached, the governor,

ordonnateur and engineer would decide on a pay scale. The

sub-engineers, who, like the engineer, were military men, were

responsible only to the engineer.

In the early years at Louisbourg recruitment of workers was divided

between the king and the contractor. For example, in 1719 the king was

to provide 10 masons and two stonecutters and the contractor was to

provide carpenters, a locksmith, and two diggers. All were given free

passage to Louisbourg.21 There appeared to be no fixed system

of wage payment. Because of the short season, craftsmen charged five

livres per day in order to earn enough to live for the whole

year.22 Other workers who knew the French colonies by

experience or reputation demanded 80 livres per

month.23 It was expected that the men would do piece work,

but it appears they had a choice. In any case those who came were hired

for three years and then could settle in the colony with free grants of

land or return to France with free passage.24 It was hoped

that the colony would soon produce its own workmen who would charge

less. Workers were solicited from Quebec; presumably they would also

have been less expensive than those from France.25 This

situation was slow to improve, however. In 1725 the contractor

complained that the workers charged too much and did little, but since

there were no others they were able to have their way.26

The labouring jobs were done mostly by soldiers. In 1720, for

example, 78 soldiers were employed in excavation, 14 in what was called

simply labouring, 4 hauling cut-stone, and 3 hauling

limestone.27 Here, too, there were shortages. In 1722 the

engineer complained that there were only 198 soldiers available for all

the work at Louisbourg; 36 more men were required for the King's Bastion

and barracks alone. Even the 200 men promised for the following year

would not be enough for all the pressing work.28 However,

sometimes when men did arrive they could not be fully employed because

of poor planning, as in 1723 when six carpenters arrived to make gun

carriages only to find that the proper wood had not been

collected.28 The list of soldiers who were working on the

bastion-barracks complex in 1724 gives the distribution of workers and

shows that some of the soldiers were skilled:30 terracers,

41; labourers, 33; sand haulers, 16; flatstone workers, 5; limestone

workers, 7; gatherers of fascine for lime kilns, 5; sawyers, 3;

carpenters (heavy timber), 4; carpenters (fine work), 4; ironmongers, 2,

and boatmen, 4. In addition there would have been a number of civilian

workers, as well as engineers and sub-engineers supervising the work. In

all probability about 150 men worked on this complex during the peak of

construction.

|

|

|

|