|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 12

Lime Preparation at 18th-Century Louisbourg

by Charles S. Lindsay

Lime Preparation in France

Limestone

Limestone, when considered as a constituent of mortar, is classified

on the basis of its ability to set under water. That which will set

produces "hydraulic lime" and contains more than 10 per cent alumina and

silica impurities. That which will not set, "non-hydraulic lime,"

contains less than 10 per cent of these elements. In general,

non-hydraulic lime is obtained from chalkbeds and oolitic limestones,

and hydraulic lime is obtained from argillaceous, siliceous,

carboniferous and lias limestones.

In the 18th century, however, limeburners, being generally uneducated

in the chemical composition of their raw materials, classified limestone

on the basis of its hardness. The darker and harder the stone, the

better lime it produced when burnt. However, the softer beds of stone

and the upper, less well-compacted beds were often used because they

were easier and cheaper to quarry.

To change the limestone into a form suitable for use in mortar it

must first be burnt, which drives out the carbon dioxide

(CaCO3 + heat = CaCO3 — CO2 =

CaO). The result is quicklime, which is then slaked with water to form

calcium hydroxide or hydrated lime (CaO + H2O =

Ca[OH]2) which, when mixed with sand to make mortar, loses

water through evaporation during setting (Ca[OH]2 —

H2O = CaO) and absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

(CaO + CO2 = CaCO3) where by the cycle is

completed and the finished product returns to limestone.1

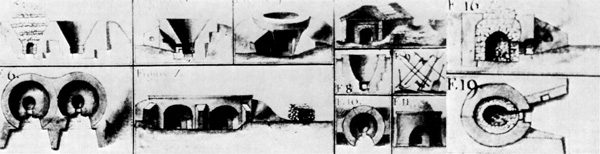

1 Eighteenth century French lime-kilns (Figs. 2-11, 16, 19) illustrated

by Masse. Described as "king's kilns," they purportedly are drawings of

actual existing structures.

(Bibliothèque du Génie.)

|

Lime-kilns

Lime-kilns, where the quarried stone was taken to be burnt to form

quicklime, were a common feature of the landscape in the 18th century,

both in limestone regions and in areas where building was taking place.

Such a ubiquitous type of structure inevitably manifested itself in many

forms, the variations being the product of regional styles, different

methods of operation, the relative longevity intended for the kiln and

the varying skills and knowledge of the builder.

A few sources of detailed information on the subject of lime-kilns

and their operation have survived from the 18th century. The most

comprehensive is a work entitled L'Art du chaufournier written by

Fourcroy de Ramecourt in 1766. This work deals in detail with the

design, operation and economics of lime-kilns, mainly along the

northeastern and eastern borders of France. The illustrations are

plentiful, detailed and well described. Diderot's Encyclopédie

contains an article on a "flare" kiln in volume 3, published in 1753,

which was copied verbatim by de Ramecourt with the comment that he had

never seen such a kiln and that it was probably an idealised version of

a type that existed in the Ardennes. In 1766, Diderot returned the

compliment by copying a section on a "running" kiln from de Ramecourt

and publishing it verbatim in the second volume of the supplement to the

Encyclopédie. A third source of information is an illustration of

several types of lime-kilns attached to a treatise on military

construction written by the French engineer, Masse, and found in the

archives of the Corps of Engineers.2 This treatise, published

in 1728, has little to say about lime-kilns, but the illustrations are

useful since they purport to be of actual examples of lime-kilns

existing in various regions of France.

2 An idealised version of a flare kiln having a sub-floor air channel.

(Encyclopédie, s.v. "Agriculture et Economie

Rustique, Fout à Chaux.")

|

A later source of information is Traité sur l'art de faire de bons

mortiers by Raucourt de Charleville. Although this work was not

published until 1828 and therefore contains some elements of design and

operation that were not known in the 18th century, it is very useful for

the detailed descriptions of the operation of kilns and the selection of

fuels. The anonymously authored Architecture rurale published in

1820 also has a few useful comments on the subject of lime-kilns.

Although there were numerous variations in design of kilns, they were

grouped in two types by most writers. The first type, known as grande

flamme or "flare" kilns, had a fire set on the floor beneath an arch

or dome supporting the load of limestone. The heat from the fire

penetrated between the stones to calcine them, without any direct

contact between fire and stone. When the load was burnt the kiln had to

be cooled before the lime could be removed. The second type of kiln,

petit feu or "running" kiln (equivalent to a draw-kiln), was loaded with

alternating layers of limestone and fuel and had openings around the

base to draw off the burnt lime. The fire was set at the bottom and

gradually worked its way up through the load. As the lower layers were

calcined, they were drawn off at the bottom and the upper layers sank

lower into the kiln. The gap at the top was filled with fresh layers of

stone and fuel, thus creating a continuously operating kiln. This type

of kiln had the obvious advantages of mass production, but also some of

its disadvantages, since the intimate contact of fuel and stone produced

a dirty quicklime compared with the product of a flare kiln.

The location of a kiln depended on the relative cost of three

elements; transport of limestone transport of quicklime and transport of

fuel. Because of this interdependency, kilns were to be found either at

the limestone quarry, near the building site, or occasionally near a

coal or wood source. According to de Ramecourt, the kilns of the Rhône

valley were situated at the spot most convenient to the quarry, whether

or not the best lime had already been removed.3 On the other

hand, the limeburners of Provence were semi-nomadic, setting up their

kilns wherever there was an immediate market and carrying their fuel

with them due to the scarcity of wood in that part of France. One effect

of this nomadism was that the limeburners, who often quarried their own

stone, used only the upper beds which were soft and easily calcined.

Unfortunately, these limestones expanded much less than most when

slaked; as a countermeasure a law was passed in Provence compelling the

limeburners to sell their lime already slaked.

3 Flare kilns from a, Provence; b, Lorraine; c and

d, Champagne. a, b and d, illustrate various

methods of loading flare kilns; c, shows in plan the common

practice of building the kiln into the side of a hill (C) with a ramp

(L) for access to the top.

(Fourcroy de Ramecourt, L'Art du

chaufournier [Paris: n.p., 1766], Pl. 3, 4, 5, 6.)

|

Flare Kilns

The simplest form of flare kiln was described briefly by

Diderot.

There are areas where they merely make holes in the ground and

arrange the pieces of limestone next to each other: they make a mouth

and a chimney and cover the holes and stones with puddled clay; they

light a fire in the centre which is maintained for seven or eight days

and when no more smoke or steam is given off the lime is supposed to

have been burnt.4 [Translation.]

The obvious cheapness of such a kiln was its main attraction to

individuals who required perhaps only a single batch of lime. However,

the saving in construction costs was partly offset by the lack of

control in the operation of such a kiln and the likelihood, therefore,

that much of the limestone would emerge uncalcined.

The more sophisticated flare kilns were often subterranean except for

the top of the wall. Such kilns were often built into the side of a hill

(Fig. 3, c) or reinforced with banks of earth. Sometimes

free-standing kilns were built, but the expense of constructing very

thick walls was prohibitive.

Most flare kilns were circular with a cylindrical interior, though

some tapered slightly toward the base (Fig. 3, b). In the late

18th, and 19th centuries, the interior form of these kilns was gradually

modified to an egg-shape truncated at top and bottom (Fig. 2).

Bottle-shaped kilns with constricted openings at the top were also known

in the 18th century, one being illustrated by Diderot.5 These

shapes resulted in less heat loss at the top.

The walls of these kilns were usually one or two pieds thick.

The author of Architecture rurale stated that the thickness of

the walls should be one-fifth the diameter of the kiln.6

Other writers contented themselves with noting that the walls should be

strong enough to withstand the heat of the fire.

Diderot's idealized kiln had a base 12 pieds square, and an

oval kiln above, 9 pieds in diameter at the widest point inside.

De Charleville noted that the bigger the kiln, the more expensive and

difficult it was to construct. The internal diameters of de Ramecourt's

kilns ranged from 6 pieds to 15 pieds, though he

recommended that smaller ones be built. The Masse illustration (Fig. 1,

16) showed a flare kiln 11 pieds in diameter, but the

accompanying text explained that these drawings were of kilns in use by

the general populace while those used in the king's works were bigger

and often found in groups of two, three, four or six.7

The best material for building kilns was brick, but this was

expensive and most kilns were constructed of whatever stone was

available. The most durable stones were granite and flint, but other

hard stones such as sandstone were adequate. De Ramecourt recommended

that mortar should not be used in those parts of the kiln exposed to the

heat of the fire,8 but rather clay mixed with water (puddled

clay). De Ramecourt also noted that in Provence, kilns were lined inside

with well-beaten clay to protect the masonry.9 Others were

lined with brick.

In Diderot's idealized kiln there was a stone-lined channel running

beneath the floor of the kiln to supply air to the fire through holes in

its arch (Fig. 2). Diderot called this an ébrasoir, De Ramecourt

recommended that more kilns should have such a flue, but by 1820 when

Architecture rurale was published, it was noted that all the

simpler kilns still lacked this feature.10 The Masse

illustrations, drawn in 1728, do not show this flue on any kiln, so one

may assume that its introduction came later and its widespread adoption

did not occur until the 19th century.

The flare kiln was loaded so as to leave a gap at the bottom for the

fire. In Provence this was done by selecting flat stones for the

construction of a corbelled dome (Fig. 3, a). In Champagne, large

stones were selected and placed radially on a dome-shaped mass of fagots

supported on stilts (Fig. 3, d). Once the fire was started, the

stilts would burn away, but by that time the weight of the limestone had

stabilized the arch.

With the dome in place, the remainder of the kiln could be loaded.

Usually the larger pieces were placed near the centre and the smaller

ones near the edge. This distribution achieved two purposes. First, the

larger stones, being nearer the fire, were more easily calcined through

to their cores, and second, since this arrangement tended to leave

larger gaps between stones, the heat circulated more easily through the

kiln. In some kilns the heat was further distributed by means of

vertical chimneys which consisted of wooden logs set upright in the mass

of stones (Fig. 3, d). These quickly burnt out and created flues

to draw the heat to the top of the kiln.

Extreme care was necessary during the firing to achieve an even

degree of burning throughout the whole load of stone. Too much heat in

one place could turn the stone to powder which "killed" it and made it

impossible to slake. Too little heat elsewhere left the stone

uncalcined. Consequently a number of precautions were taken. First, the

opening at the base of the kiln, through which the fire was fed and the

burnt lime was later drawn off, was situated on the side opposite the

prevailing wind, and often was further sheltered with a sunken approach.

When the fire was started this opening was controlled by a door or by

masonry blocking which regulated the air supply to the fire. Second, a

wind baffle was erected around the top of the kiln. In some kilns this

was a fixed wall; in others the baffle was a moveable wooden screen

(Fig. 3, b). Third, on top of the kiln itself the limestone was

covered with large flat stones roughly set in clay, leaving a few holes

for smoke to escape.

The most complete description of the firing of a flare kiln is given

in de Charleville.

Whatever the size of the kiln one should always start with a slow

fire, especially for new kilns.

The nature of the stone which often breaks when the fire seizes

it, and the nature of the wood can alter the duration of the slow-firing

from twelve to forty-eight hours.

At the start of the firing the stone becomes wet, the water which

comes out covers the surface, and it is not until eight or twelve hours

after the fire has been lit and burning gently and continuously that the

stone is completely dry. Then the smoke sticks to the stone which

becomes black; one must increase the strength of the fire a little and

keep it to the same heat until the smoke is completely burnt off, which

will be noticed because the stone returns to its original colour:

subsequently one can safely gradually increase the intensity of the fire

and carry it to its highest point.

The fire is increased in intensity in the ratio of 1, 2, 3, 6, so

that after thirty-six hours it is at its maximum heat....

One knows that the lime is burnt when the top of the kiln does not

give off any more smoke, when the load of lime settles about one-sixth

of its total height, and when the centre of the mass of stone is a nice

bright red and whitish pink. All the degrees of fire mentioned can be

recognized by the colour of the flame that escapes from the top of the

kiln. Generally it appears first black, brown, then red, then violet,

finally blue, and it finishes by being yellow and white that is scarcely

visible.11 [Translation.]

Other authors described similar processes but there is some

disagreement as to the length of time necessary for firing. Diderot

stated that the normal firing time was 12 hours which seems rather short

but still within the 12-to 48-hour range of de Charleville.12

On the other hand it is difficult to equate Diderot's figures with those

of de Ramecourt, who suggested that a firing lasted four to six

days.13

4 Cross-section and plan views of a type of flare kiln, found in Alsace,

with a rectangular furnace and two openings for fueling fires set

beneath the two tunnel arches of limestone. This type of kiln was

designed to ensure more even burning throughout the load of limestone.

(Fourcroy de Ramecourt, L'Art du chaufournier

(Paris: n.p., 1766], Pl. 7.)

|

There were also some differences of opinion concerning the best type

of wood fuel for flare kilns. De Charleville went into the subject most

thoroughly and came to the conclusion that the best woods were pine,

aspen, willow and fir because they burnt with a lot of flame and little

smoke.14 Green wood could be used if it had been heated and

dried before being placed in the kiln. De Charleville recommended that

the fire be started with fascines of brush-wood and reeds, then brought

to a higher temperature with white woods, followed by oak and a resinous

wood to keep the fire at maximum heat.15 However, Diderot

stated that fascines of brushwood were sufficient for the whole firing,

and many of the kilns described by the Ramecourt used this fuel

exclusively.16 For those kilns using other woods, de

Ramecourt recommended poplar since it flamed very easily.17

Per Kalm on his travels through Quebec in 1749 noted that cedar was

there regarded as one of the best fuels.18 The Masse treatise

commented that the kilns shown in the illustrations were normally fired

with brushwood or pine fagots, but that the king's kilns were fired with

coal.19 It is not certain, however, whether he was referring

to flare or running kilns. De Ramecourt and de Charleville recommended

coal only for the latter.20

In Alsace there was an unusual type of flare kiln that was square

with a low central partition and two arched entrances (Fig. 4). The

partition served principally as a ledge for the jambs of the two

tunnel-like arches of limestone that ran through to the back wall. The

tunnel shape and the use of two arches resulted in an easier and quicker

circulation of heat through the mass of stones.21 A

modification of this type of kiln was used to fire bricks and tiles at

the same time as calcining limestone. However, the method was not

economical in France, and contraction of the limestone caused

disturbance and distortion of the bricks and tiles lying on top.

Running Kilns

It appears from the statements of contemporary writers that by the

mid-18th century, running kilns were as common as flare kilns for

supplying large amounts of lime.

The most common interior shape was an inverted cone or pyramid. The

latter shape was used when the kiln was fired with wooden logs and was

necessary to allow the large pieces to entirely cover the inside of the

kiln. Inverted cone-shaped kilns were usually fired with coal, partly

because it was cheaper, and partly because the smoke from burning

vegetal matter, including wood, was believed to block the pores of the

limestone and make calcination difficult.

De Ramecourt believed that the best type of running kiln was found in

Flanders. His description of it was copied verbatim into the supplement

of Diderot's Encyclopédie, together with a reproduction of the

illustrations (Fig. 5), which show a double-walled circular kiln

approximately 11 pieds high with a shallow loading ramp built at

a tangent. The interior of the kiln was an inverted cone, 7 pieds

in diameter at the top, decreasing to 20-28 pouces at the

cendrier or ash-box which was 15-17 pouces deep (Fig. 5,

4, G). Around the base of the kiln there were three draw-holes,

12-13 pouces wide, closed by metal doors that opened into the

cendrier (Fig. 5, 5, F). Access to these was gained by

means of short covered passageways which ran through the body of the

kiln (Fig. 5, 2, D). In those kilns that were built into the side

of a hill, access to these passageways would necessitate excavating long

sunken pathways into the hillside. To avoid this expensive task such

kilns were frequently built with a circular covered corridor around the

kiln wall giving access to all the drawholes (Fig. 5, 8, 9). The

drawhole arches were supported by iron bands since they were subject to

damage when the lime was being drawn off (Fig. 5, 7, i). At

springer level each of the drawholes had an iron bar running across the

opening and anchored in the masonry jambs (Fig. 5, 7, e). Other

iron bars were laid across these iron bars spanning the cendrier to form

a grille on top of which the fuel and limestone were placed (Fig. 5,

5, E). To load this type of kiln the limeburner

arranges three or four armfuls of well dried wood [on top of

the grille] which he covers with a layer of three or four pouces

of coal in pieces the size of a fist....

Then the limeburner takes a basket of pieces of limestone... and

throws them upon the bed of coals...: he roughly arranges these pieces,

usually with his foot... so they cover all the coal. On top of the bed

of stones which is called a charge and is 3 or4 pouces

thick at the most, he spreads a bed of coal or charcoal.... The

limeburner repeats the same sequence of charge and charcoal until

the kiln is completely filled. He is careful only to make the

charges a little thicker the higher he goes, especially toward the

centre of the kiln where the fire is often hottest.22

[Translation.]

To fire this kiln the following method was used.

To light it a bundle of straw is thrown into the cendrier

to which is added a few pieces of dry wood; the drawhole into which

the wind is blowing most directly is the one chosen [for lighting

the fire]. If the wind is too strong, such of the other drawholes as

will carry the flame out of the cendrier are closed. In a few

minutes the wood on the grille catches fire; when it is burning well and

smoke starts to come out of the top of the kiln, all the drawholes are

blocked with stones and earth or sods so the fire does not burn too

quickly.23 [Translation.]

5 A running kiln from Flanders. a, plans and elevation; b,

Fig. 4, cross section; Fig. 5, enlarged plan view of the cendrier

with the iron bars in place; Fig. 6, a rod for removing the burnt lime;

Fig. 7, one of the doors so the cendrier; Figs. 8 and 9, plan and

cross-section through a similar kiln with an encircling tunnel for

access to the drawholes.

(Supplément à l'Encyclopédie, s.v.

"Chaufournier.")

|

6 Running kilns from a, the Rhône valley, with a pillar occupying

the cendrier; b from Méziers; c, from Maubenge, a simple

type that was operated as a hybrid flare/running kiln.

(Fourcroy de Ramecourt, l'Art du

chaufournier. (Paris; n.p., 1766], Pl. 14, 15.)

|

The fire was then left to burn its way up through the lime. When all

the fuel at the bottom of the load was consumed, the limeburner opened

each of the drawholes in turn and removed the bars of the grille. The

burnt lime then immediately fell into the cendrier where it was

shoveled into barrows and carted away, while the load above settled

further into the kiln. Once the bars had been removed at the base,

drawing off the lime became an almost continuous process that was

carried out equally from all three drawholes to minimize uneven slumping

of the load. As the process continued, the drawholes gradually became

blocked with ashes. When this happened, the bars were forced back into

position and the ashes cleared out. These ashes could then be sold for

mixing into mortar that was to be used in damp places.24

At the same time as the lime was being drawn off at the base of the

kiln, more stone and fuel were being added at the top in the void

created by the slumping and settling of the mass within the kiln. It was

from the continuous nature of the firing and loading process that these

kilns were known as fours coulants or running

kilns.25

De Ramecourt stated that he had seen kilns similar to those from

Flanders in the Rhône valley (Fig. 6, a). They were more simply

made from local fieldstone, usually sandstone, and mortar was used as a

bonding agent, but the over-all shape was similar with the exception of

a short pillar occupying what would have been the cendrier. This

pillar served two purposes: first, it supported the wooden planks that

carried the load of fuel and limestone in a manner similar to the iron

bars in the Flanders kilns; second, it channeled the burnt stone to the

three drawholes by dispersing the mass of stone as it descended through

the kiln.26

Other types of running kilns were used for different fuels. It seems

that hard limestones were often burnt with charcoal in special

cylindrical kilns, though de Ramecourt could see no reason why ordinary

kilns could not be used.27 However, many limeburners did not

like charcoal as a fuel since it was supposed to make the lime "bitter"

and difficult to mix with sand. These kilns were approximately 10

pieds in over-all diameter, but only 4.5 pieds wide

inside, and up to 18 pieds high (Fig. 6, b). There was a

single opening at the base with a short flue running to the centre of

the kiln.

In Picardy a very simple type of kiln was used for burning soft

limestones. These inverted pyramid kilns were 5 pieds wide at the

top and 6 pieds high. They were cut into the earth and lined with

brick, leaving a single opening at the base. Peat was the normal fuel

for these kilns.28 No illustration is given of this type of

kiln, but it sounds very similar to the simple lime-kiln structure

number 47 found at Jamestown, Virginia in a late 17th-century

context.29

Finally there was a type of kiln that was neither flare nor running

yet had characteristics of both. This kiln, commonly used by individuals

for a single load of lime, was a circular structure 18 pieds in

diameter. It consisted of a shallow depression with a stone-lined

channel running to the centre from a small pit on the perimeter (Fig. 6,

c). Baskets of medium-sized stones were thrown into this hollow

forming a flat layer. On top of this a thin layer of powdered coal was

laid leaving a gap around the edges. On top of the powdered coals

alternating layers of coal and stone were laid up to a height of 14

pieds. The whole cone-shaped mass was then plastered over with

clay and the lower parts were reinforced with stone.30

This kiln can hardly be described as a flare kiln since the fuel and

limestone were arranged as for a running kiln. But, since the kiln had

to be demolished to be emptied, it does not qualify as a running kiln

either. As with the simple flare kiln described by Diderot, this one was

cheap to build but the cost of lime from it was high.

Slaking

After lime had been burnt to form quicklime, it had to be slaked to

form a hydrated lime suitable for mixing with other materials to make

mortar. Slaking involved adding water to the lime, which absorbed it as

water of crystallization, giving off heat up to 300°C. and causing

rapid expansion. During slaking, especially with hydraulic limes, the

silica and aluminum impurities combined with the lime to form

cementitious compounds that were insoluble in water. This resulted in a

mortar capable of setting under water. A non-hydraulic lime could be

converted to an hydraulic lime by the addition of various materials

(e.g., pozzolana, crushed tile, burnt shale).

Slaking had to be carried out as soon as possible after burning since

the quicklime was liable to absorb moisture from the atmosphere and

start spontaneous air-slaking, which reduced the quicklime to a pulpy

powder that would not properly expand when fully slaked.

There were two methods of slaking described in numerous 18th-century

treatises on building. One which most authors accredited to Philibert de

Lorme, but which probably was a very ancient method of slaking, was

designed to produce large quantities of high quality lime that could be

stored and used over a long period of time. The other was better suited

for producing lime to be used immediately.

Although Diderot claimed that de Lorme's method was an old-fashioned

one, it was still described in 1777 by J. F. Blondel as the best method

of slaking lime.

The best way to slake lime is to put in a pit the number of stones

of quicklime that one thinks one will use, after having crushed them

with a sledge-hammer to reduce them to pieces of almost equal size, in

order that they may be slaked equally. It is then necessary to cover the

lime equally over-all with one or two feet of good sand, and throw onto

the sand as much water as is necessary to sufficiently soak it and slake

or fuse it without burning; if the sand cracks and allows the smoke to

escape, the holes are at once covered with fresh sand, after which the

lime can be left to rest as long as one wishes: it will become smooth,

rich, and perfect for masonry.31 [Translation.]

A slightly different description of de Lorme's method in Diderot

advised a wait of two or three years before using the lime.32

One treatise written in 1743 stated that lime made this way would keep

for 20 years.33 Another treatise written in 1728 recommended

lime slaked by this method for lining walls and backing frescoes, since

it did not absorb the paint.34

The second method of slaking was more efficient since it enabled the

mason to eliminate unburnt lumps of limestone from the mass of lime in

the initial slaking process (Fig. 7). Again, Blondel gave the most

complete 18th-century account of this process.

In order to rid the limestone of lumps which may occur in it, one

takes precautions in this respect where building is being carried out

that requires some care. Consequently, one digs two pits, next to each

other and of unequal size, which are joined by a channel. The smaller,

which is at the same time higher, is used for crushing the quicklime,

and retaining the lumps found there; the larger is intended to serve as

a sort of reservoir, designed to contain a load of slaked lime

proportionate to the size of the building to be erected. In order to let

into the latter pit only what is supposed to get there, one takes care,

not only to place a grille of wood or iron in the channel, to stop all

the larger pieces, but also to keep the bottom of the smaller pit higher

toward the channel, in such a way that the lumps are caught there. These

precautions having been taken, one cleans thoroughly the first pit and

fills it with lime on which one first pours a little water to start the

slaking: while that water is being absorbed one pours on more until the

lime is completely dissolved, after which one pours on more to conclude

the slaking, taking care to stir it and work it well during this

operation with a wooden rabot. It is necessary to avoid using too

much or too little water; too much water will drown the lime or lessen

its strength, and too little on the other hand will burn it, destroy the

pieces and reduce it to powder. The lime held in the small pit, having

been sufficiently stirred many times over, is run off by itself into the

larger one by opening the communicating channel, continuing to stir

until the pit is empty. Then, one closes the passage and immediately

repeats the operation until the second pit is full. Finally, when the

lime thus slaked has taken on a little hardness in the large pit, one

covers it with one or two feet of sand, in order to be able to keep it

as long as is desired, and use it when one needs it, without fear that

it will lose its quality.35 [Translation.]

7 Plan (Fig. I) and cross-section (Fig. II) of

slaking and storage pits. The lime was slaked in the smaller circular

pit (A), then run off through a channel (C) to a large rectangular

storage pit (B).

(Jacques Françoise Blondel, Cours

d'architecture (Paris: Desaint, 1771-77], Vol. 5, Pl. 64.)

|

Briseux wrote that after the lime had been poured into the larger

basin it was watered for four or five days until no more cracks appeared

and the lime became one homogeneous mass, after which it was covered

with sand.36

There are two articles by different authors in the

Encyclopédie dealing with slaking that describe a similar

procedure to that of Blondel except that one of them, in contradiction

to the other, states that too much water will not hurt the lime, and

cautions only against using too little water.37 Diderot

regarded the main advantage of this method to be its ability to provide

lime for immediate use, and, therefore, made no mention of covering the

lime in the larger pit with sand.

De Charleville, writing in 1828, made no mention of de Lorme's

method, but did describe in detail a method similar in principle to the

second one described by Blondel.38 It differed in the use of

a wooden tank instead of the smaller pit, although he did note elsewhere

that a pit may sometimes be used. De Charleville agreed with Blondel,

against Diderot, that a very precise amount of water should be used, but

he also concurred with Diderot against Blondel, that the purpose of this

method was to provide lime to be used almost immediately.

One method of slaking for high-quality lime was to make a depression

in the centre of a mound of sand into which was placed some quicklime.

The quicklime was watered and covered with a layer of sand for seven or

eight hours until the slaking was completed.39 By this method

the lime turned to a fine powder rather than the pulpy mass resulting

from the other methods.

Other methods of slaking that came into use in the 19th

century—immersion, complex and spontaneous slaking—were

mentioned by de Charleville and other later authors.40

De Lorme's method was not mentioned in any of the available

19th-century sources. Instead the emphasis was on the method described

by Blondel. The reason for this is clear: de Lorme's method was not

susceptible to mass production in any age when the scale and speed of

production were becoming ever greater. His method involved a long wait

between slaking and use. By contrast, Blondel's method, especially as

seen by de Charleville, was ideally suited to continuous production.

There is, therefore, the same movement from intermittent to continuous

production in slaking as occurred in the burning of lime.

|