A Brief History of Canada's National Parks

Chapter 4

National Parks in Quebec

Introduction

Public-spirited citizens advocated the establishment of a national park in the Province of Quebec as early as 1912, but nearly 60 years elapsed before the objective was realized. Barely a year after the formation of the Dominion Parks Branch of the Department of the Interior, in 1911, Ottawa newspapers published letters proposing that a park be established in the Gatineau River watershed north of the nation's capital. In a letter to the editor of the Ottawa Citizen on November 12, 1912, James M. Macoun, a biologist for the Geological Survey of Canada, suggested that part of the uninhabited region between the Gatineau and Coulonge rivers, north and west of Chelsea, Quebec, be set aside for the purposes of a national park.

Macoun's proposal was brought to the attention of the deputy minister of the Interior by the Commissioner of Dominion Parks, J.B. Harkin, who recommended that the Government of Quebec be consulted. The suggestion was approved and, on December 23, 1913, Commissioner Harkin wrote to the Honourable Charles Devlin, Minister of Colonization, Mines and Fisheries for Quebec.

Mr. Harkin asked Mr. Devlin if the Province of Quebec would be willing to establish a national park in the Gatineau district. Devlin's Deputy Minister, S. Dufault, replied by letter on January 3, 1914, that the matter would receive his minister's careful attention and would be brought to the attention of his colleagues. No further reply was ever received.

Public interest in the establishment of a national park in Quebec was maintained for some years in a desultory fashion by occasional newspaper articles and by talks by prominent conservationists at public gatherings. In 1922, J.B. Harkin arranged for the compilation of a report outlining a possible location for a national park in western Quebec, north of the Ottawa River and east of the Gatineau River, and the advantages that would result from its reservation. The report, prepared by town-planning expert Thomas Adams, was supported by maps and photographs of outstanding scenic features of an area containing about 10,360 km2.

In 1931, an organization known as the Fish and Game Protective Association for Gatineau, Hull, Papineau and Pontiac Counties of Quebec began to lobby for the establishment of a national park in western Quebec. Its executive met with Thomas G. Murphy, Minister of the Interior, who expressed sympathy for the proposal but was unable to take any action until it was evident that Quebec would make lands available for a park.

In July, 1937, the Honourable Onésime Gagnon, Minister of Mines and Fisheries for Quebec, and his Deputy Minister, L.A. Richard, interviewed the Honourable Thomas Crerar, federal Minister of Mines and Resources, about the possibility of having a park established in Quebec. Although they reviewed the steps involved in the establishment of a national park, no positive action resulted from the meeting.

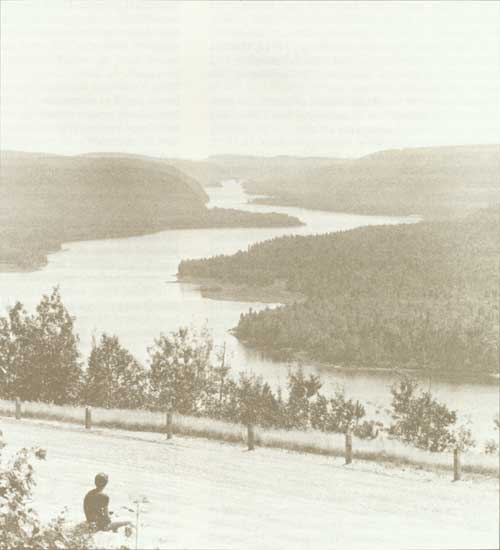

Lake Wapizagonke, La Mauricie National Park

Numerous Representations Made

By early 1940, representations made to the Government of Quebec aroused the interest of the officials responsible for the administration of parks. On February 15, Deputy Minister Richard sent a letter to Frank Williamson, Controller of the National Parks Bureau in Ottawa, enquiring whether the Government of Canada would consider the establishment of a national park in Quebec if his minister opened negotiations.

Evidently, the efforts of the Quebec government officials to have a national park established in the province were sincere, for in February, 1941, the Honourable Emile Côté, Minister of Lands and Forests, reopened the subject with Thomas Crerar. Mr. Côté suggested that a joint federal-provincial survey of possible sites would help to lay plans for a new national park in the post-war period. Mr. Crerar agreed that there was little likelihood that a park would be established before the end of World War II, but said that the federal government would participate in a joint inspection of any site Mr. Côté had in mind.

In the early summer of 1941, James Smart, Controller of the National Parks Bureau, and Ernest Menard, general inspector for the provincial Department of Mines and Fisheries, jointly inspected the Gaspé provincial park area.

Mont Tremblant Area Examined

National parks officials were unable to examine the Mont Tremblant provincial park area until March, 1943, when James Smart, accompanied by the author, spent several days assessing the capabilities and attractions of the southern portion of the park and adjoining privately owned land on which services for visitors had been developed. In June, Controller Smart returned to the Mont Tremblant region and examined areas that had not been readily accessible during our winter visit. Preliminary reports describing both the Mont Tremblant and Gaspé provincial park areas were later compiled and held for reference.

Although the establishment of a national park in the Province of Quebec seemed to be within reach by early 1944, the provincial government's interest apparently collapsed following an election in August that year. The Liberal administration was defeated and succeeded by the Union Nationale party under the leadership of the Honourable Maurice Duplessis. For the next 16 years, the political climate in Quebec was unfavourable to the transfer of provincial lands to the federal government for the purposes of a national park.

In June, 1960, however, the Liberal party, headed by Jean Lesage, regained power in Quebec. Lesage had been federal Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources — the Minister responsible for the administration of national parks — from 1953 to 1957, and hopes were now high that an offer of lands for a national park in Quebec would be forthcoming. On November 7, the Honourable Walter Dinsdale, federal Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources, wrote to Premier Lesage to inform him that the federal government would welcome any proposal to establish a national park in Quebec. Lesage replied that the Honourable Lionel Bertrand, Provincial Secretary, had been delegated to take up the matter with Mr. Dinsdale. Later in November, during the Federal-Provincial Tourism Conference in Ottawa, Bertrand discussed the possibility of a national park in Quebec with Ernest Côté, Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs and National Resources. Bertrand mentioned that he had in mind the transfer of Mont Tremblant Provincial Park to federal administration.

Mr. Dinsdale received communications from members of Parliament representing several Quebec constituencies, all of whom appeared eager to support the establishment of a national park in their province. Following a series of public meetings at various cities and towns in Quebec in the autumn of 1962, the Tourism Council of Quebec submitted a brief to Provincial Secretary Bertrand. It contained 18 major recommendations, one of which strongly endorsed the establishment of one or more national parks in Quebec.

During the 1962 Federal-Provincial Tourism Conference in Ottawa, Bertrand advised Assistant Deputy Minister Côté that early in 1963 he again would be raising the matter of a national park in Quebec.

Changes in Political Power

In April, 1963, the Liberal party won the federal election, and Walter Dinsdale was succeeded by the Honourable Arthur Laing, Member of Parliament for Vancouver South, as Minister responsible for national parks. Laing lost little time in assuring Premier Lesage that the new federal government would welcome proposals for the establishment of a national park in Quebec. The files do not contain a reply from Lesage, and any hope for his participation vanished on June 5, 1966, when his party was defeated in a provincial election.

Land Studies in Quebec

Although Arthur Laing had been unable to reach agreement with the Province of Quebec, other forces and activities were leading to the establishment of a national park in the province. On January 21, 1966, A.T. Davidson, Assistant Deputy Minister for rural development in the federal Department of Forestry and Rural Development, advised Ernest Côté, who was now Deputy Minister, that his branch was participating in a large-scale rural development project in the lower St. Lawrence region. The project, whose objective was a comprehensive development plan for nine counties, including the Gaspé region, was being undertaken by the Agricultural Rehabilitation Development Act (ARDA) program, through which agreements providing for development of marginal or sub-marginal lands were possible. The financing of such projects was shared by the appropriate provincial government and the federal government.

In November, 1966, Mr. Côté received from Guy Lemieux, Director of Policy and Planning for the Department of Forestry and Rural Development, a copy of the final draft of the plan prepared by the Bureau d'Aménagement de l'Est du Québec [Bureau of Management of Eastern Quebec]. Of the 10 volumes in the report, volume 5, which covered the tourism sector, was of particular interest to National Parks officials at Ottawa, because it recommended the establishment of a park at the extremity of the Gaspé Peninsula.

Gaspé Peninsula Investigated

In February, 1967, Arthur Laing asked Deputy Minister Côté what sites had potential for national park status if the political climate respecting national parks in Quebec should change. Côté replied that no field studies had been undertaken in Quebec for 20 years, and suggested the initiation of basic studies concentrated within the 322-km belt between the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers, with special attention to the Gaspé Peninsula, where studies had indicated that tourism and park development could stimulate the depressed economy.

On June 14, Lloyd Brooks, Chief of the Planning Division, National Parks, was invited by ARDA to participate in a short tour of the Chic-Chocs mountain region of the Gaspé Peninsula. A study team including Paul Boisclair, Director of the Montreal-based ARDA region; Pierre Franche, Assistant Director; Chester Brown, former ARDA recreation land controller; and Lloyd Brooks completed a three-day reconnaissance in September. Its assessment, conducted by air and ground surveys, focused on two regions — the Chic-Chocs and Gaspé Provincial Park.

The proposed Gaspé area, which incorporated most of the Forillon peninsula east and north of the town of Gaspé, also had been studied thoroughly by a team of two landscape architects engaged by the Bureau d'Aménagement de l'Est du Québec. Its report, submitted in July, 1966, contemplated a park area of about 300 km2, featuring archaeological, historical and cultural attractions.

The ARDA-National Parks study team found the Gaspé region, with its appealing open seascapes and picturesque fishing villages, to be similar in character to Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island. It concluded that, if the means could be found to retain several of the key fishing villages in their existing form and to maintain the open landscape of marginal farmland, the peninsula could be developed as an outstanding national park.

Administrative Changes

Changes in the federal Cabinet and in National Parks administration in 1968 had a significant influence on the future establishment of parks in the Province of Quebec. Arthur Laing was appointed Minister of Public Works on July 5, and was succeeded as Minister responsible for national parks by Jean Chrétien, Member of Parliament for St. Maurice, Quebec, who had been Minister of National Revenue. J.R.B. Coleman retired as Director of the National and Historic Parks Branch in April, and was succeeded by John I. Nicol. Jean Charron, formerly Chief, National Parks Service, became an Assistant Director of the branch.

Jean Chrétien, a native of Shawinigan, Quebec, a lawyer, sportsman and lover of the out-of-doors, promptly identified himself as a strong exponent of the extension of the national parks system. He was familiar with the work undertaken to have Quebec represented in the system, and his inclusion in the Cabinet as member for a region with strong national park potential added strength to the national parks movement.

In a series of talks to his constituents and others, Chrétien stressed the role of national parks in conservation. At the annual meeting of the Lake St. John Fish and Game Association at Saint-Félicien on November 10, 1968, he urged the establishment of national parks not only in his province but also in others. He added that, to meet the public demand for recreation without impairing the conservation program, 40 to 60 new national parks should be developed before 1985. Of those parks, he hoped that five to ten would be in Quebec.

Federal-Provincial ARDA Agreement

The support and assistance of officers responsible for the administration of ARDA eventually was reflected in the completion of an agreement dated May 26, 1968. The agreement, which provided for the economic development of the lower St. Lawrence, Gaspé and Îles-de-la-Madeleine, was signed on behalf of Quebec by Premier Daniel Johnson, and on behalf of Canada by the Honourable Maurice Sauvé, Minister of Forestry and Rural Development. Clause 55 of the agreement was of special interest to National Parks administrators in Ottawa:

... Canada shall undertake to develop a park in the Forillon Peninsula. The land shall be acquired by Quebec and leased, free of charge, to Canada for a period and under conditions acceptable to both parties.

On the strength of this commitment, Jean Chrétien was able to seek a closer association with the provincial government in the establishment of a national park in Quebec. He stepped nearer to the goal on September 19, when he met with the Honourable Gabriel Loubier, Minister of Tourism, Fish and Game for Quebec. After an hour of solid discussion, during which Chrétien dwelt exhaustively on the benefits that would accrue to the province from a national park, officials of both governments joined their ministers to learn the basic elements of the agreement in principle.

Chrétien and Loubier had agreed that at least one park, and preferably two or three parks, should be established in Quebec, and that lands in the province would be provided to the federal government for park purposes by 99-year lease. The term lease was a necessary compromise because Mr. Loubier was unable to promise fee simple ownership of land to the federal government. A lease would be renewable or, alternatively, administration of the park would revert to provincial control, with perpetuation of the park assured. The administration and operation of the park and the provision of amenities would reflect the linguistic duality of Canada and, more particularly, the cultural character of the region and the province.

An agreement was drawn up by officers of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, discussed with officials of the Ministry of Tourism, Fish and Game for Quebec, and left with the ministry for study and comment. As well, Quebec officials and officers of Canada's national parks system completed a reconnaissance survey of the proposed boundaries of the new park.

Forillon Park Agreement

The fiscal year 1969-70 was a busy one for officers of the National and Historic Parks Branch engaged in negotiations with their counterparts in the Province of Quebec. Much of the liaison fell to Jean Charron, who was fluent in English and French and was conversant with the political concerns and the personalities of the Quebec negotiators. National Parks officers undertook inspections of the Forillon peninsula and discussed details with officials of Quebec's Ministry of Tourism, Fish and Game.

On April 16, 1969, addressing an enthusiastic Chamber of Commerce at Gaspé, Jean Chrétien outlined his efforts to reach an agreement with the Quebec government to establish a national park on the Forillon peninsula. He stressed the importance of a national park to the region, stating that a park would provide an incentive for visitors to remain longer in the area and would furnish a strong stimulus to the current efforts of the tourism industry in neighbouring portions of the Gaspé region.

On May 21, Chrétien formally announced in the House of Commons that the governments of Canada and Quebec had reached an agreement for the establishment of the first national park in Quebec, on the Forillon peninsula. As outlined by Mr. Chrétien, "the province of Quebec will place the site of the Gaspé park at the disposal of the government of Canada for a period of 99 years. The agreement states, as well, that the province of Quebec will have the right to regain possession at the end of 60 years on repayment of all federal capital expenditures incurred by the federal government during the 60-year period. In either case, the government of Quebec agrees that the land would be used for the purposes of a park and conservation in perpetuity. This arrangement is renewable by agreement of the two parties."

Policy to be Maintained

The provision in the agreement for tenure of the park land for a determinate period rather than for outright ownership drew questions from the federal leader of the opposition. On May 30, the Honourable Robert L. Stanfield asked in the House of Commons whether the policy for national parks had been changed and whether the government was "now prepared to offer to all provinces arrangements relating to national parks on the same terms as the minister arranged with the province of Quebec regarding the national park in Gaspé." Mr. Chrétien replied: "We have no intention of changing our policy on parks or of signing new agreements of the same nature, and the federal government is legally the owner of the land in the Forillon peninsula". Prime Minister Trudeau explained that the Province of Quebec had insisted, under the terms of the ARDA agreement, that the transfer of this particular territory be for a limited time: "Speaking for the government, I have no intention of signing any further agreements with provinces, including Quebec, which would permit this kind of arrangement."

Formal Agreement Signed

Intensive preparatory work by officials of the federal and provincial governments permitted the completion, on June 8, 1970, of a formal agreement confirming the establishment of the first national park in Quebec. This agreement, which gave birth to Forillon National Park, was signed on behalf of Canada by Jean Chrétien and on behalf of Quebec by Madame Claire Kirkland Casgrain, Minister of Tourism, Fish and Game, and by Gerard D. Levesque, Minister of Inter-governmental Affairs.

It was widely known that the acquisition of privately owned land required for the establishment and development of the new park would result in the relocation of a substantial number of the local inhabitants. On July 17, the National Assembly of Quebec gave assent to the Forillon Park Act, the terms of which enabled the government to acquire ownership of any land necessary for the park. Title to the park land was registered in the registry office for Percé, Quebec, in right of the Government of Canada on July 22, 1970, and was formally accepted under the authority of the governor in council for Canada on July 27, 1971. When a number of amendments to the National Parks Act received royal assent on May 7, 1974, a description of the lands contained in Forillon Park was incorporated in the schedule to the act.

Additional Park Area Sought

By April, 1969, strong public sentiment for the establishment of an additional national park was evident in the Shawinigan area of Quebec, and during the following months resolutions from numerous municipalities and chambers of commerce were received in the office of the minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. On May 30, a conference of mayors of municipalities in central Quebec, held at Trois-Rivières, adopted a resolution urging the provincial government to reach an understanding with federal authorities for the establishment of a national park in the valley of the St. Maurice River. On June 21, a committee for the establishment of a national park in the area known as La Mauricie was formed in Shawinigan.

The National Parks administration began to study the area north of Shawinigan and Grand Mère in the heart of La Mauricie to determine its potential as a national park. The study area, embracing portions of Champlain and St. Maurice counties, was composed of some 518 km2 lying west of the St. Maurice River, south of the Matawin River, east of Lac Wapizagonke and northwest of the city of Grand Mère. Punctuated by lakes, rivers, mountains and valleys, it represented a typical example of the Laurentian Plateau.

Jean Chrétien, accompanied by John Gordon, his senior Assistant Deputy Minister, and Denis Major, a national parks planner for the federal government, made a brief aerial reconnaissance of the area. They flew over several small lakes north of Grand Mère, continued up the St. Maurice River to its junction with the Matawin, proceeded east for 13 km and then turned southeast and passed over a chain of lakes including Lac des Cinq and lacs Édouard, Isaïe, a la Pêche and des Piles. By automobile, they visited Lac à la Perchaude, Lac à la Pêche and Lac la Truite. Their brief survey confirmed that the area contained the natural requisites for a national park.

Land Exchange Possible

From the mid-1960s, the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), then part of the National and Historic Parks Branch, had actively tried to maintain adequate populations of migratory waterfowl throughout Canada by leasing or purchasing wetlands. In 1969, CWS purchased approximately 2,300 ha at Cap-Tourmente, on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River about 48 km east of Quebec City, to protect the habitat of the greater snow goose.

Subsequently, CWS was confronted with the prospect of surrendering some of its land to Hydro-Quebec, which wished to acquire a site for a phase of its operation in the Cap-Tourmente area. Jean Chrétien referred the matter to Prime Minister Trudeau for advice. Mr. Trudeau suggested that it might be appropriate to study, with the Province of Quebec, the exchange of land at Cap-Tourmente not essential to the sanctuary but essential to Hydro-Quebec for land elsewhere in the province suitable for a national park. The prime minister clearly stated that any exchange should be unconditional as to title and should have the conditions normally associated with national park lands in other provinces.

Discussions at Quebec

On July 23, Jean Chrétien met in Quebec City with Gabriel Loubier, Minister for Tourism, Fish and Game for Quebec. After long discussion, Loubier agreed to an exchange of land at Cap-Tourmente for land in the St. Maurice-Matawin River area considered suitable for a national park. Loubier requested that Chrétien first complete arrangements with the city of Shawinigan for the inclusion in the proposed park of Lac a la Pêche, the source of the city's water supply, and also obtain general agreement from Consolidated-Bathurst Limited for the establishment of a national park on lands for which it held timber leases essential to its paper-manufacturing operations.

On August 14, Assistant Deputy Minister J.H. Gordon informed J.I. Nicol, Director, National and Historic Parks Branch, that Mr. Chrétien had obtained from the mayor of Shawinigan a copy of a letter addressed to Mr. Loubier confirming that the city was prepared to surrender its rights to Lac a la Pêche and environs for national park purposes. As well, the minister had received from the vice-president of Consolidated-Bathurst a letter indicating the company's willingness to waive its timber rights in those parts of the St. Maurice area that would be included in a national park.

Meetings with the Paper Company

In September, Jean Chrétien requested information on the forest stands and pulpwood production in the proposed La Mauricie park area and comment on the effect that withdrawal of timber-cutting privileges would have on Consolidated-Bathurst and the National and Historic Parks Branch. Meetings of the paper company and the branch were held in Ottawa on October 8 and in Grand Mère on October 24. Officials from Consolidated-Bathurst claimed that timber rights in the proposed park area represented a tangible asset in the magnitude of $1,500 for each 2.6 km2 of leased area and that the phasing out of part of its operation in the St. Maurice Valley would result in a loss of two million dollars a year to the local economy. J.G. MacLeod, Vice-president of the woodlands division of Consolidated-Bathurst, suggested that consideration be given to an alternative area east of the proposed site that was held under lease by Domtar Limited.

Discussions with Consolidated-Bathurst revealed that the company owned outright about 26 km2 of the proposed park area; that its leasehold contributed to the operation of four mills; and that a 13-km2 forest experiment station was located within the park site. Company officials expressed the hope that a multiple-use type of park might be considered, but national parks officers explained that such was not possible under the terms of the National Parks Act.

The meetings with Consolidated-Bathurst prompted John Carruthers, Chief of the National Parks Systems Planning Section, to report that the site of the park would be hard to defend unless alternative areas had been examined. He also stated that if it was decided to establish the park in the area under review, consideration should be given to the deletion of the company's leasehold, including areas on which tree plantations had been established. He recommended that the company continue to use the Matawin and St. Maurice rivers for log and pulpwood drives.

Formal Agreement Prepared

Meanwhile, a draft agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of Quebec providing for the transfer and control of the land described in the schedule had been prepared by a legal officer of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. It provided for an unqualified transfer of land from the province to Canada, and contained commitments by both parties to prevent exploration for or development of minerals, to prevent pollution of any waters and to prevent impairment to the flow or quality of waters within or flowing through the park. The agreement also provided for the transfer of certain lands within the Cap-Tourmente wildlife sanctuary to the Province of Quebec.

Mr. Chrétien forwarded the agreement to Mr. Loubier at Quebec City on November 4, 1969. Loubier acknowledged its receipt and remarked that he was hopeful that it would be submitted to the Quebec Cabinet for study and discussion during the week following.

Alternative Area Examined

The suggestion by officers of Consolidated-Bathurst that National Parks officials examine an alternative area for a national park in La Mauricie was not overlooked. In fact, a strong lobby for a site east of the St. Maurice River had developed, backed by the town council of La Tuque and supported by other communities. On February 4, 1970, John Carruthers and Gerald Lee, of the National Parks Systems Planning Section, made a reconnaissance flight by helicopter over an area northeast of Grand Mère and the St. Maurice River. In spite of very cold weather, it was possible for them to observe about 70 per cent of a 1295-km2 area, and to obtain an appreciation of its potential as a national park. The area contained two large lakes, Mékinac and Missionnaire, in a physical setting common to the Laurentian plateau and having a general elevation of about 305 m above sea level. Most of the area was under lease to two large paper-manufacturing companies, and one logging camp was visible.

The party observed nine dams, which kept the levels of a number of small lakes in the area artificially high. Saint-Joseph-de-Mékinac, a small settlement of about 400, occupied the centre of the area, and a wide right-of-way for a power line scarred the eastern portion, which also was traversed by a railway line servicing La Tuque. There were summer cottages on the shores of some lakes and a few sandy beaches. Most of the forest roads, which had been opened by Canadian International Paper Limited, had been made available to visitors, and picnic sites had been developed along some of them. Although the area appeared to have potential for both summer and winter recreation, existing resource development and general public use detracted from its suitability as a national park.

Delay in Reaching Agreement

The hopes of federal government officials for an early completion of the park agreement forwarded to Gabriel Loubier in November, 1969, were not realized. At a meeting in Quebec City on February 23, 1970, Jean Chrétien and officers of his department discussed with ministers of the Quebec government some matters affecting the establishment of national parks in the province. The Honourable Marcel Masse, Minister of State in the Government of Quebec, advised the meeting that the provincial government had approved the principle of establishing a national park in the St. Maurice Valley, although the specific location of the park would have to be confirmed. Masse also stated that Quebec would recover the rights to prospect for minerals, and that, on transfer to Canada, lands would be free from all encumbrances. Later, on April 19, the Honourable J-J. Bertrand, Premier of Quebec, wrote to Prime Minister Trudeau to confirm that the provincial government had approved the establishment of a national park in the St. Maurice region and that he had so informed the president of the La Mauricie National Park Committee on March 18.

Election to be Held

By late winter, however, a provincial election had been called, and in central Quebec the establishment of a second national park became an issue.

The results of the election held on April 29, 1970, brought defeat to the Union Nationale government, which was again replaced by a Liberal administration. Federal officials promptly initiated negotiations with Claire Kirkland Casgrain, Quebec's new Minister of Tourism, Fish and Game, to complete the proposed agreement on La Mauricie Park. On July 2, Jean Chrétien forwarded to Prime Minister Trudeau a memorandum to council seeking authority to enter into the proposed agreement with the Government of Quebec. The order in council received approval on July 8, 1970.

La Mauricie Agreement Signed

A little more than a month later, on August 22, the federal-provincial agreement covering the establishment of a park in the St. Maurice River Valley was signed at St-Jean-des-Piles — 11 km northeast of Grand Mère. The document was signed on behalf of the Government of Quebec by Claire Kirkland Casgrain, and on behalf of the Government of Canada by Jean Chrétien.

Prolonged negotiation on land acquisition between officers of the two governments delayed expropriation proceedings by Quebec. Eventually, Quebec and Canada agreed that Lac à la Pèche and land to the southeast would be included in the park, and a bill providing for the establishment of La Mauricie Park was introduced in the National Assembly in March, 1972. It was given third reading on May 12 and received the assent of the lieutenant governor on May 16. The new act authorized the lieutenant governor in council to give the Government of Canada free possession of the lands set out in Schedule "A" to the act. It also authorized the minister of Public Works for Quebec to acquire or to expropriate any right or property within the proposed park area. Documents covering the expropriation of the lands concerned were registered in the Land Registry Office at Shawinigan. Quebec, on August 3, 1972.

Formal transfer of the administration, management and control of the park lands was made by letters dated October 16, 1972, and July 4, 1973, from the minister of Public Works to the minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development for Canada, pursuant to provincial legislation. The inclusion of Lac à la Pêche in the park was contingent on Canada's recognition of Shawinigan's right to continue using the lake water for its water system. These water rights were later outlined in a formal agreement between the city and the Government of Canada.

In June, 1974, authority to resurvey the perimeter of the lands for La Mauricie National Park, according to provincial survey instructions by a Quebec land surveyor, was granted by the Surveyor General of Canada. A revised plan and description of the park boundary was completed in May, 1975. After title searches had been undertaken by an agent of the minister of Justice, the director of legal services for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development advised the Director General of Parks Canada, J.I. Nicol, on October 11, 1976, that surveys and an amended description of the lands concerned were sufficiently satisfactory to permit formal acceptance of title for the purposes of the national park. Authority for such acceptance was obtained by order in council dated December 9, 1976.

National Park Proclaimed

The order in council cleared the way for completion of the remaining formalities: the transfer to the Province of Quebec of a portion of the Cap-Tourmente wildlife sanctuary, as provided for in the formal agreement of August, 1970; and the proclamation as La Mauricie National Park of the lands transferred to Canada by Quebec. The transfer of the Cap-Tourmente area was accomplished by the terms of Order in Council P.C. 1977-1225 of May 5, 1977. The proclamation, authorized by order in council of May 12, 1977, was published in The Canada Gazette of June 25, 1977, and two subsequent issues.

Forillon and La Mauricie national parks will be remembered not only as exceptional physical attractions but also as outstanding achievements of Jean Chrétien, Member of Parliament for St. Maurice, while Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. His ambition to have Quebec represented in Canada's system of national parks had been realized through ingenuity, persistence, logic and persuasion.

Descriptions of the new national parks and their development for public use will be found in succeeding paragraphs.

Forillon National Park

The establishment of Forillon National Park in 1970 extended the national parks system to the Province of Quebec and ensured the preservation, as a national heritage, of a spectacular portion of the Canadian landscape bordering the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The park occupies much of the eastern portion of Cap Gaspé known as the Forillon peninsula and contains an area of 238 km2. Its interior constitutes a typical example of the Gaspesian mountain region — the easterly end of the Appalachian range, which extends from a point deep in the United States north and east to its extremity in the Forillon peninsula.

Long before the establishment of a national park in the area was considered, the Gaspé region was a cherished destination for many touring motorists. The completion of the Perron Boulevard (now Highway 132) in the mid-1920s provided an entrancing 402-km drive from Sainte Flavie on the lower St. Lawrence River to the town of Gaspé on the Bay of Gaspé.

For most of the route, the road skirts the St. Lawrence River and the gulf, passes picturesque little fishing settlements, climbs steep grades, and descends to coves with sandy or pebbled beaches. As the motorist continues easterly, the views become spectacular. The mountains slope upwards on the right, the seashore becomes more precipitous, and off in the distance, far from the highway, the almost vertical limestone cliffs of Forillon peninsula rise from the sea. A complete circuit of the Gaspé Peninsula, a journey of about 885 km, provides one of the most spectacular motor drives in eastern Canada.

Early History

"Gaspé" is believed to be an Indian word, probably Micmac, meaning land's end. It referred to the prominent rocky cape that is the first land seen on approaching the Gulf of St. Lawrence from the southeast. The name has been applied not only to Cap Gaspé, originally called "Honguedo" by Jacques Cartier, but also to the Bay of Gaspé and the entire Gaspé Peninsula.

Archaeological investigations have revealed evidence that humans inhabited the Gaspé Peninsula centuries before Cartier's recorded landing at the Bay of Gaspé in 1534. It is believed that groups of hunters migrated from the south and west to the Gaspé territory 10,000 years ago and lived by hunting big game — probably caribou — and by catching fish and gathering wild fruit. Traces of this prehistoric occupation have been found in ancient stone tools on the Penouille peninsula in the Bay of Gaspé.

The early history of Gaspé is irrevocably bound to the fishing industry for which it became famous. Cabot's documented voyages to North America in 1497, Verrazano's in 1524, and Cartier's landing in the Bay of Gaspé in 1534 influenced the westward movement of European fishermen to the shores of Newfoundland, Acadia and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. For years, however, few fishermen from abroad wintered in Canada, for they cured their catches of cod along the shores and sailed for home before winter.

Of the early navigators, Jacques Cartier is best remembered. Under the authority and with the assistance of King Francis I of France, Cartier sailed westward from St. Malo on April 30, 1534, to find a route to India. He landed off Newfoundland in mid-May, then passed through the Strait of Belle Isle to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. On July 24, he landed near the present site of the town of Gaspé and, in the presence of a group of Indians, raised a nine-metre wooden cross bearing a shield and an inscription claiming possession of the adjoining territory for the King of France. Four centuries later to the day, Canada's National Parks Branch erected a cross to commemorate Cartier's landing. Hewn in one piece from Vermont granite, this nine-metre cross occupies a prominent site in Gaspé overlooking the harbour.

Indian Occupation

Although the Indians met by Jacques Cartier in 1534 were Iroquois and Hurons, the earliest Indian residents of the Gaspé area were Micmacs, members of the Algonquin confederation who came regularly on summer expeditions to the rich fishing grounds around Gaspé Peninsula. A migratory people, the Micmac hunted in the woods in winter and moved in the spring to the seashore to gather shellfish and to angle at the mouths of rivers. Indian settlements still exist at Restigouche, Carleton, Maria and Gaspé. A presumed Indian camping site on the Forillon peninsula is now known as Anse-aux-Sauvages (Indian Cove).

The Cod Fisheries

Little was known of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Gaspé region before Jacques Cartier's first voyage to North America. Although early entrepreneurs had hoped to trade in furs as well as in fish, the abundance of cod led to its dominance in the region's economy.

For more than a century, fishing operations by Europeans were migratory. Vessels engaged in the Gaspé fisheries had to be of substantial size, for they had to carry the fishermen, provisions for a six-month stay, fishing gear, chaloupes and large quantities of salt. The only supplement to the sailors' diet was that obtained from small gardens planted ashore, meat from occasional hunts, and, of course, cod and mackerel.

The pursuit of cod and other species of fish off the shores of Gaspé dates back as early as 1542, when Jean Alphonse, Roberval's pilot, commented on the quantity and quality of the species available. France had an excellent market for fish and also had large quantities of salt required for what was known as the green cod fishery. Green curing was the salting of fish on board the mother ship, which left for the home port when full. Alternatively, the dry cod fishery was dry curing on land, which required less salt and also left more room on board ship for cured fish. Usually, Gaspé cod were more easily dried than those caught off Newfoundland because they were smaller.

Sedentary fishing from year-round settlements in the Gaspé region was slow to take form. The dry curing of fish onshore along the Gaspé coast reduced the need for the transportation of large quantities of salt from France and allowed more space on ships returning home with the catch. Eventually, sedentary fisheries were established at several points around the Bay of Gaspé and also along the gulf coast to the south at Percé, Grande-Rivière, Pabos, Port-Daniel and Paspébiac.

The French regime in Gaspé ended during the Seven Years War. The French stronghold at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island fell to Brigadier-General James Wolfe and Major-General Jeffrey Amherst in July, 1758. In early September, Wolfe and a fleet of at least 15 ships entered the Bay of Gaspé and wiped out the settlements. About 6,000 quintals of fish were destroyed, four schooners and 200 chaloupes seized, and most of the 300 inhabitants rounded up for transportation to France via Louisbourg.

Although fishing as a livelihood for residents of Gaspé has probably declined from the status enjoyed in the 19th century, it is still carried on from communities along the gulf coast. Much of the catch, which includes cod, redfish and herring, is taken with the aid of large boats known as seiners, longliners and draggers, and is processed and marketed from centres such as Rivière-au-Renard, Paspébiac and Grande-Rivière. Other industries, including agriculture, lumbering and tourism, also provide employment for residents.

Fishing Communities Preserved

The park boundary along the northeast coast of the Gaspé Peninsula was drawn approximately 1.6 km from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to permit the continued existence of eight long-established communities between Rivière-au Renard and Cap-des-Rosiers. Near Trait Carré, the boundary was extended to accommodate a reception centre for park visitors arriving over Highway 132 from the west.

An almost continuous belt of settlement along the shores of the Bay of Gaspé also was excluded from the park. In the park's southeastern section, including the Forillon peninsula, the owners or occupants of lands and buildings within the communities of Cap-des-Rosiers-Est, Petit-Gaspé, Grande-Grève, Anse-aux-Sauvages (Indian Cove) and Cap Gaspé were required to leave when their holdings were expropriated by the Quebec government. Displaced residents received compensation for their lands and buildings from the province and, with one exception, the names of all expropriated communities were retained. The area around the main visitor activity centre, formerly located within Cap-des-Rosiers-Est, was renamed Le Havre. Proposals for the development of the park called for the retention and renovation, where required, of a number of buildings, including an ancient church. Some of these structures are used in the interpretation program.

Evacuation of Park Lands

Before some of the major developments in Forillon National Park could be initiated, the evacuation of park lands within the newly established boundaries had to be arranged. Altogether, about 2,500 separate parcels of land were involved and slightly more than 205 families were affected. Under the terms of the federal-provincial agreement, the Government of Quebec was responsible for vesting titles to park lands in right of Canada and for paying compensation for land acquired. All privately owned land required for park purposes was carefully examined by professional valuators engaged by the province and financial settlements were made on the basis of valuations.

In addition to cash settlements for expropriated land and buildings, former residents were entitled to a relocation grant of up to $2,000. A great many of them obtained employment in Gaspé and Rivière-au-Renard. Later, the provincial government constructed low-cost modern housing units in Gaspé, Cap-des-Rosiers and Rivière-au Renard and made them available to 110 families.

Early Park Planning

Although the formal agreement between Canada and the Province of Quebec to establish Forillon National Park was not completed until 1970, the National Parks administration began to prepare for development of the park following Jean Chrétien's announcement in the House of Commons in May, 1969.

A provisional master plan detailed the development concept for the park. It provided for resource conservation, definition of major use areas and their development, transportation within the park, visitor services and interpretation. The plan designated future land use by grouping areas in classes to protect natural and cultural features. These classes were (1) special preservation areas containing unique fauna and flora; (2) wilderness recreation areas with access restricted to non-mechanized transportation systems; (3) natural environment areas serving as buffers between preservation and development areas; and (4) general outdoor recreation areas. As a result, lands in Class 1 would be restricted to interpretation, study and observation, and lands in Class 2 to interpretation, hiking, horseback riding, fishing and observing nature. Lands in Class 3 would permit interpretive and outdoor activities such as camping, picnicking, boating, swimming, fishing and using a major road corridor; and those in Class 4 would permit recreational use and visitor activity centres.

Conceptual Plan

The conceptual plan proposed five major public-use centres. Cap-des-Rosiers-Est, on the gulf coast — since renamed Le Havre — was designated the main activity centre. Petit-Gaspé, on the Bay of Gaspé, was designated a sub-centre, and Cap Bon Ami, Grande-Anse and Penouille peninsula were designated secondary activity centres. The plan also envisaged the construction of a scenic parkway to provide access to lookout points, picnic areas and walking trails. To reduce the need for main thoroughfares, transportation facilities to move visitors from a central point to key locations also were proposed. The experience of outdoor life was to be enhanced by the development of campgrounds, hiking trails and picnic areas.

Public Hearings

In 1971, the National Parks administration made available the preliminary development plan, supported by maps and plans, for discussion and review at public hearings in the town of Gaspé on November 17 and in Rimouski on November 19. Recommendations made at these hearings or in briefs and letters received from individuals and organizations resulted in several changes to the plan. Following a review of all suggestions and objections, a revised master development plan was produced.

One major change to the preliminary plan was the decision not to proceed with the construction of a scenic parkway wholly within park boundaries. Responding to the wishes of community groups from L'Anse-au-Griffon and Cap-des-Rosiers, National Parks officials decided instead to relocate portions of the Laurencelle Road linking Cap-des-Rosiers on the gulf and Cap-aux-Os on the Bay of Gaspé, and to reconstruct the entire length of the road. They also decided to close to the public the secondary road between L'Anse-au-Griffon and a point on the Bay of Gaspé east of Penouille. This road now functions as a service road and multiple-use trail closed to vehicular traffic, and thus helps to conserve the area as a wilderness zone.

Early Development

The development of Forillon National Park began in 1970. Robert Marois, a bilingual officer of the National and Historic Parks Branch at Ottawa, was appointed superintendent. He established an administrative headquarters in the town of Gaspé and began to recruit a warden service, an interpretation officer and support staff.

The establishment of visitor services, including camping and picnic facilities, had priority. Camping was provided at Cap Bon Ami, a few kilometres east of Le Havre on the gulf coast, where a small provincial campground had existed, and at Petit-Gaspé on the Bay of Gaspé. A day-use area for bathing and picnicking was developed on the Penouille peninsula, for which tractor trains provided transportation to and from a 300-vehicle public parking area on the mainland.

Highways and Trails

The relocation of Highway 132 between Le Havre (Cap des-Rosiers-Est) and the Bay of Gaspé, now known as the Laurencelle Road, began in 1972. A system of hiking trails also was begun, and among the early routes completed were those leading to Cap Bon Ami and to Cap Gaspé.

Another achievement was the development of an interpretation program for the park. Guided hikes introduced visitors to the flora, fauna and geological character of the Forillon peninsula. The park naturalist also undertook off-season studies of birds and mammals, geology, forest cover, and marine wildlife.

Park Activity Centres

The activity centres, which have been developed along the main thoroughfare — Highway 132 — or along park roads leading from the highway, are probably the greatest attraction for visitors. The centres are staffed by park personnel who are fully conversant with the features and amenities available in the park, and who are able to answer questions or to provide assistance when required.

At Trait-Carré, about 4.5 km east of Riviere-au-Renard, a park reception centre was constructed where visitors may obtain information, maps, brochures and suggestions for fuller enjoyment of the park's attractions. Le Havre, the park's main activity centre, has many attractions. A sheltered harbour with modern wharves provides anchorage for fishing vessels, and visitors may join the daily boat excursions operated by private enterprise along the coastline of the Forillon peninsula to its extremity, Cap Gaspé. Adequate parking for motor vehicles is available, and a modern campground provides accommodation. Day-use areas with washroom facilities and camp-tables also help to make picnicking enjoyable.

A new interpretation centre opened in Le Havre in 1983. Located on a site eminently suited for its purposes, the centre includes a theatre for audio-visual programs and a variety of exhibits explaining the geology, fauna, flora and marine life of the park and the Forillon peninsula and is a base for guided hikes along the rugged and precipitous shoreline.

Changes at Forillon

Over the centuries, Forillon peninsula has undergone great physical changes. About two kilometres southeast of Le Havre, this eastern extension of the Gaspé Peninsula narrows into a headland with sheer walls rising as much as 215 m above the sea. In his descriptive book La Gaspésie, Alfred Pelland states that Forillon is the remains of a mountain that in 1851 was precipitated into the sea. Apart from its almost vertical cliffs, the peninsula's most prominent feature is a lighthouse that guides navigators past the formidable headland.

Cap Bon Ami

A three-kilometre drive southeasterly along the Gulf of St. Lawrence takes visitors to Cap Bon Ami, where another modern campground has been developed. This area is very popular with hikers, for it is the starting point for a scenic trail that encircles Mont Saint-Alban — one of the higher points on the peninsula — and commands views of both the gulf and the Bay of Gaspé to the south.

Petit-Gaspé

Petit-Gaspé lies about four kilometres east of the junction of the Laurencelle Road and Highway 132 on the Bay of Gaspé. It is accessible over what is known as the "peninsula" road. One of the oldest of the former fishing communities on the bay, Petit-Gaspé was a tourist attraction even before the national park was established. The community's original settlers migrated from the British Channel Islands, and one of its outstanding show-pieces is St. Peter's Anglican Church, a small chapel that helps to link early settlement and commercial endeavours with the present.

At Petit-Gaspé, an adequate parking area, a modern campground, and picnic areas provide the usual amenities for visitors, and closeby are the sites of an early lead mine and a grist mill operated by the Simon family. In an outdoor amphitheatre, the park's interpretation service shows films, presents talks on features of the natural environment, and sponsors other activities. During the winter months, visitors are encouraged to ski along the peninsula road and adjacent trails.

Grande-Grève

At Grande-Grève, an original Gaspé settlement has been re-created to illustrate the national park theme — Harmony between man, the land, and the sea. This recreation, which includes the restoration of old houses, commercial buildings, and other structures that formed a part of the original settlement, is intended to portray the traditional life-style of Grande-Grève. It presents a look back at the self-sufficiency of the farmer-fisherman; at cod-fishing as an essential economic activity; at the monopoly of the trading company operating in the vicinity; and at the physical environment, social organizations, and socio-economic development of the settlement up to the present.

Grande-Grève has adequate parking for vehicles, a wharf where boats may tie up, and stretches of beach where scuba diving may be enjoyed.

Indian Cove and Cap Gaspé

Following a "walk-about" among the buildings and former dwellings at Grande-Grève, visitors may complete their tour of the Forillon peninsula with a trip to its rugged and towering extremity at Cap Gaspé.

The peninsula walking trail is the final leg of the journey. A hike of about three kilometres leads to the lighthouse, which marks the eastern extremity of Gaspé Peninsula and provides nightly guidance to vessels plying the gulf or entering the Bay of Gaspé.

Fort Peninsula

A return westerly over the peninsula road to Highway 132 takes visitors to a heavily settled belt of land bordering the Bay of Gaspé, which was excluded from the park because of its concentration of population. Highway 132 recrosses the park boundary just east of its junction with the road up L'Anse-au-Griffon Valley, which is now closed to public-owned vehicles.

About 1.5 km west of the boundary is one of the most interesting features in the area — Fort Peninsula — a relic of Canada's participation in World War II. After the collapse of France in the summer of 1940, plans for the defence of the Atlantic coastal area were expanded. In August, a Canadian-American Permanent Joint Board of Defence was formed. At a meeting in Ottawa on August 27, the board adopted a recommendation that both underwater and harbour defences be completed at Halifax, Sydney, and Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and Gaspé, Quebec. Gaspé had become very important to naval planners because of its suitability as an anchorage for fleets of British or American warships in the event that Great Britain was invaded.

The Fort Peninsula installation comprised part of a naval base constructed on the Bay of Gaspé during the summer of 1941 at Sandy Beach on the south shore of the inner Gaspé harbour, four kilometres east of the town of Gaspé. Two fixed-defence batteries also were constructed — Fort Peninsula on the north side of the Bay of Gaspé just east of Penouille, and Fort Prevel on the south shore of the Bay of Gaspé almost opposite the tip of Forillon peninsula.

The Gaspé naval base was never attacked, nor were its guns ever fired in anger, but it was a point of great activity. During 1942, 23 ships, including two warships, were sunk in the Gulf of St. Lawrence by enemy submarines. The base not only exercised control over naval countermeasures, but also assisted in the rescue and care of survivors of sinkings.

Occupation of Fort Peninsula was discontinued in June, 1945, following the end of the war. With the exception of the two large bombardment guns, the site was cleared of wartime installations. Park visitors may now freely use a park picnic area with benches, tables and other day-use amenities.

The Penouille Area

The Penouille peninsula has the finest bathing beaches and the warmest sea water in the park. Playground areas and a service building have been constructed nearby, and visitors may use dressing rooms and washrooms and obtain light meals and food supplies at a lunch counter.

In the 19th century, Penouille and Anse-aux-Cousins, across the Gaspé harbour, were the sites of whaling operations, but whaling from Gaspé waned as the whale population declined from over-killing, and by 1867 the industry was no longer viable.

A Hikers' Paradise

I have mentioned some of the opportunities for recreation awaiting visitors to Forillon National Park, notably swimming, bathing and underwater exploration. For hikers, the network of trails throughout the park is most attractive. In addition to excursions along the rocky and precipitous shores of the Forillon peninsula, pedestrians can find much of interest along the undulating and leafy trails leading through the hilly or mountainous areas of the western portion of the park. These excursions may vary in length, according to personal choice, from a few kilometres to all-day trips of up to 30 km.

Conclusion

Forillon National Park is a key element of tourism in the Gaspé Peninsula, for it is strategically situated at the entrance to the Gaspé-Perce tourist route. Long before the area was completely redeveloped as a national park, visitor attendance was increasing annually. During the fiscal year 1974-75, more than 300,000 visitors were recorded; by 1978-79, visitation had reached 650,000; and in 1980-81, nearly 730,000 visitors were recorded. As Forillon's unique attractions become more widely known, it is expected that public use will continue to increase.

La Mauricie National Park

La Mauricie National Park, a typical example of the Quebec Laurentian mountain area, was established in August, 1970, to preserve as a national heritage a representative example of the Laurentian Shield. The park theme is Laurentian Heritage, and its numerous wooded hills, lakes and streams contrast sharply with the lowlands of the St. Lawrence River Valley. Almost equidistant from Quebec City and Montreal, the 549-km2 park is easily accessible from Trois-Rivières, about 50 km to the south.

La Mauricie's physical outline resembles a huge horseshoe, with the St. Maurice River forming its eastern boundary, the Matawin and St. Maurice rivers enclosing its northern limits, and a chain of long, narrow lakes flanking its western boundary. The southern boundary follows a surveyed line in the form of an arc, extending north from the Shawinigan River to a point south of Lac Écarte, and then southeast to the southern limits of Lac à la Pêche.

Three large natural corridors lie within the park: the valleys of Lac Wapizagonke and Lac Anticagamac; the valleys of Lac à la Pêche, Lac Édouard and Lac des Cinq; and the valley of the St. Maurice River. The last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, sculptured the round hills, clear lakes and sandy beaches within the park area. Although traversed through the timeless past by early nomads, including Indians, the area has never been settled permanently and is an oasis of peace and tranquillity. Its forests of various species of hardwood and evergreen shelter an abundant and varied fauna. Criss-crossed by numerous rivers and dotted with many small bodies of water, the park appears to have been designed by Nature for the purposes of both conservation and recreation.

Before the park was established, much of the area was held under timber leases by Consolidated-Bathurst paper company, which operates large mills in the nearby cities of Grand-Mère and Shawinigan. More than a dozen private clubs, most of them established for sport fishing, operated here from 1890 to 1970, leasing their building sites from the Government of Quebec. Today, all private interests in the park have been extinguished, but three club buildings have been retained for use as a park warden station, a public shelter (Wabenaki) and a youth camp.

Private use of the lands that now form the park left few scars because access was possible only over primitive roads and trails or by canoe or aircraft. Consequently, the relative wilderness of the park has allowed carefully planned development to provide amenities necessary for its use and enjoyment by the public.

La Mauricie is well situated to meet the recreational needs of a highly industrialized area of Quebec. The development of hydro-electric power along the St. Maurice River at La Tuque, Grand-Mère and Shawinigan Falls, now known as Shawinigan, has contributed to the manufacture of paper, newsprint, aluminum and chemicals. Shawinigan contains Canada's oldest aluminum smelting plant, which was established in 1900. From the early 1900s until 1963, when its rights and properties were taken over by Hydro-Quebec, the Shawinigan Water and Power Company generated much of the electric power required in central Quebec.

Prehistoric Occupation

Archaeological studies have confirmed pre-European occupation of the La Mauricie region by members of North American Indian tribes, probably of the Algonquin confederacy. More than 30 sites used in prehistoric times have been identified along the banks of or on islands in lacs Wapizagonke, Caribou and Anticagamac. This chain of lakes along the western side of the park formed a natural route to penetrate northern areas by canoe from the great waterway, the St. Lawrence River. Although Indian occupation of these sites was largely transitory, evidence of use is found in the form of blackened stone hearths, primitive stone tools and pictographs, or rock paintings, which adorn a steep cliff of Lac Wapizagonke.

After Laviolette's founding of a trading post known as Trois-Rivières at the junction of the St. Maurice and St. Lawrence rivers in 1634, fur traders and Indians favoured the canoe route through rivers and lakes of the La Mauricie region to avoid the Iroquois nation, which had established control over the upper St. Lawrence River. The route lost much of its commercial prestige, however, after the founding of Ville-Marie (now Montreal) in 1642. Destined to become the nation's metropolis, Ville-Marie rapidly became a very important trading centre and siphoned off much of the early fur trade.

Iron Deposits Developed

Another early development in the region was Canada's first iron and potash industries at Les Forges du St. Maurice, about 11 km northwest of Trois-Rivières. The complex operated from 1730 until about 1883. In 1923, on the recommendation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to commemorate Les Forges du St. Maurice, the National Parks Branch of the Department of the Interior erected a stone cairn supporting a bronze tablet. Fifty years later, in May, 1973, the governments of Canada and Quebec entered into an agreement that permitted Parks Canada to plan, develop and operate Les Forges du St. Maurice as a national historic park.

The Forest Industries

Before the iron industry reached its apex in the region of La Mauricie, the harvesting of the forests in this part of Quebec had begun. Rights to cut timber over large areas were obtained by Quebec entrepreneurs in 1831 and the years following. The first log shanty for winter forest operations was built by Edward Grieve in the vicinity of Lac à la Pêche in 1830. By 1852, timbered lands in the St. Maurice River area were held by at least 10 individuals or companies, one of whom controlled 3,522 km2 and another, 4,921. Among the operators of these large holdings were George Baptist, George B. Hall, Gilmour and Company, and the William Price Company.

The lumber trade subsequently employed thousands of lumberjacks along the St. Maurice and Matawin rivers and their tributaries. Some of the timber was sawn into lumber for domestic use, but a great proportion was shipped from Trois-Rivières or Quebec to Great Britain or exported by rail to the United States. The first timber slide on the St. Maurice River at Shawinigan Falls was built in 1852, no doubt to facilitate the passage through turbulent waters of square timber, a product greatly in demand for many years by Great Britain.

The Shawinigan Water and Power Company's construction of hydro-electric power facilities at Shawinigan Falls between 1898 and 1903 led to the development of the area as a centre for the pulp and paper industry. For many years, the leading manufacturer was the Laurentide Paper Company. Eventually, its assets, together with those of competitors, were acquired by Consolidated Paper Company Limited, which merged with Bathurst Paper Limited in 1967 to form Consolidated-Bathurst Limited. As outlined earlier, rights held by Consolidated-Bathurst Limited within the boundaries of La Mauricie National Park were repossessed by the Government of Quebec to facilitate the establishment and development of the new national park.

Planning and Development

Following the federal-provincial agreement on August 22, 1970, to establish a second national park in Quebec, the director of the National and Historic Parks Branch at Ottawa took steps towards its development. By early 1971, administrative offices had been obtained in the city of Shawinigan and the first park officers had been appointed. These officers — Alfred Tremblay, superintendent; Fernand Dionne, works manager; Gilles Ouellette, park naturalist; and Jean LaFrance, chief park warden — all had previous experience in natural resource administration either in Quebec or in Ontario. As development of the park proceeded, park personnel changed. In 1978, when the District of La Mauricie was created, the responsibilities of the superintendent of La Mauricie National Park were expanded to include supervision of the administration of Les Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Park.

In December, 1970, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development contracted with Sereq Incorporated of Montreal to prepare a master plan for the development of La Mauricie Park. The plan, which was submitted to the National and Historic Parks Branch in July, 1971, provided for the preservation of substantial portions of the park where ecological studies had revealed the presence of fauna and flora of special interest. The planners suggested that it was possible, by limiting the access of visitors to zones of unusual ecological concern, to concentrate zones of development in the southern part of the park, which was more accessible, and, by providing diversified activities, to make this portion of the park a major area of attraction for visitors.

Park Zoning

The planners recommended that the park be divided into four zones. Zone 1 would consist of areas having rare, unique or representative qualities. It would preserve and protect, among other things, landscapes, forest cover, fauna and archaeological sites. Zone 2 would incorporate wilderness areas, in which public activities would be restricted to hiking, cross-country skiing, canoeing, sport fishing and primitive camping. Zone 3 would consist of natural environment areas, in which developments might include primitive campsites, canoe campsites and trails leading into wilderness areas and might provide departure points for back-country use. Zone 4 would consist of outdoor recreation areas, and would make provision for permanent developments for visitor use, including a parkway and secondary roads. It would include campgrounds, picnic areas, observation points, a convenience store, canoe rental facilities, parking areas and visitor reception centres. General access to developed areas would be provided by a parkway linking the eastern entrance near Saint-Jean-des-Piles to the western entrance near the village of Saint-Mathieu.

Following studies, committee meetings and internal decisions, many of the planning contractor's proposals for the development of the park were adopted. In September, 1972, a provisional management plan for the development and operation of La Mauricie National Park was completed by the planning section of the Quebec Region Office under the direction of Denis Major, Regional Planning Chief. It provided for a fifth zone to accommodate intensive-use areas, permitting activities classed as almost urban in character.

Residents of the region were invited to express their opinions on the proposals for the new park at public hearings in Saint-Jean-des-Piles, Saint-Mathieu, Saint Gérard-des-Laurentides, Grand-Mère, Shawinigan and Trois-Rivières. Among the projects endorsed was the construction of the parkway, with suggested increases in the number of road-side rest areas, picnic grounds, and points of access to adjacent lakes.

Park Development

Following the appointment of park personnel and the establishment of essential conservation services, early appropriations made provision for construction of access roads, a clean-up of the shores of the larger lakes and the development of major activity centres. A contract was awarded for the survey, clearing and construction of a parkway providing access to activity centres and permitting initial contact with the rich natural environment.

The first entrance to the park was developed near the village of Saint-Mathieu, following reconstruction of a road connecting the southern end of Lac Wapizagonke with provincial Highway 351. Another entrance was opened in 1974 at the southeast corner of the park, approximately six kilometres north of Saint-Jean-des-Piles, to offer direct access from the city of Grand-Mère. The first of five major activity centres was developed near the southern end of Lac Wapizagonke. Named Shewenegan, it occupied part of the property of the former Shawinigan Club, one of the largest clubs expropriated for park purposes. This area, which was opened to public use in 1972, provided a picnic ground, a beach, walking trails, a temporary interpretation centre, a lunch counter and a boat rental concession and served as a major departure point for canoeing and canoe-camping. The Mistigance campground, with service buildings and an amphitheatre, also was available to the public in that area of the park. In November, 1978, a final master plan was completed by the planning division of the Quebec Region of Parks Canada and approved by the federal minister responsible for national parks, the Honourable J. Hugh Faulkner.

Forest Fire Protection

From the beginning, the protection of forests from fire has been a concern of La Mauricie's administrators. Rather than depend on a system of fire roads for the transportation of fire-fighting equipment, the warden service charters, from private enterprise, aircraft equipped for landing on water. Natural landing areas for helicopters have been identified in each of 15 sectors of La Mauricie, and the park is a member of the Quebec-Mauricie Conservation Corporation, from which assistance may be obtained when the suppression of large or difficult fires is beyond the capabilities of the park staff. In 1980, the park's resource conservation service was able to control and suppress five separate fires in difficult terrain.

The Parkway

The most costly project undertaken in La Mauricie National Park was the construction of a 62-km parkway linking the eastern and western entrances and facilitating the visitor's first contact with this representative example of the Laurentian mountain wilderness. Separate contracts were awarded for clearing the right-of-way and for construction. The shorelines of many of the large lakes to which the parkway provided access were cleaned of driftwood, dead brush and flotsam.

In locating the road, park planners had sought to provide easy access to the various areas selected for visitor use, to make visible the spectacular scenery of the region, and to carry out construction at a reasonable cost. Construction began in 1972 and ended in the autumn of 1980 at a cost of 22 million dollars, including paving.

The parkway may be travelled throughout its length from either the eastern or the western visitor reception centre. The following is a brief description of the route from the eastern entrance, a few kilometres north of Saint-Jean-des-Piles.

The eastern visitor reception and interpretation centre, which was completed in 1982, is less than one kilometre north of the park boundary. It consists of several buildings, including parking facilities, a warden station, interpretation displays and a multiple-use theatre. From here, the parkway skirts the St. Maurice River for several kilometres and, after crossing Rivière à la Pêche, brings the motorist to the first major development area. This area, named Rivière à la Pêche, is open year round, and has been designed to offer special assistance to handicapped persons. It provides opportunities for camping, hiking and, in winter, skiing and has an amphitheatre for evening interpretation programs.

The next point of interest is Lac Bouchard, where a picnic area has been constructed to assist handicapped persons. From here, the parkway leads to Lac du Fou, where visitors may enjoy fishing and canoeing and picnicking. Eventually Lac du Fou will be an ideal point of access to back-country hiking trails. A little farther on, the visitor reaches Lac Édouard, the second major development area of the park. This area provides a wide variety of outdoor activities, including water sports, canoe-camping, picnicking, hiking and fishing and has an excellent beach, a snack bar, and a canoe-rental concession.

On the northern side of the parkway from Lac Édouard is Lac Soumire, which has a parking area for 70 vehicles. Lac Soumire is the main point of access to the Lac des Cinq corridor, which offers excellent fishing and canoe-camping. From Lac Soumire, the motorist continues westward to Lac Écarté, one of the largest bodies of water in the park. There is parking and excellent fishing here. A little farther on is Lac Alphonse, where the waters are reserved for fishing by senior citizens (65 years or over) and picnic tables and parking are provided.

Spectacular Area

Leaving Lac Alphonse, the visitor enters one of the most spectacular lengths of the parkway. The roadway climbs by easy switchbacks to a prominent lookout, Le Passage, which rewards the traveller with a magnificent southern view of the main expanse of Lac Wapizagonke. An interpretive exhibit at this viewpoint introduces visitors to the origin of the landscape of the Wapizagonke valleys. Proceeding downhill, the route crosses the north end of Lac Wapizagonke, which is nearly 16 km long. The Wapizagonke-north development area, accessible over a short sideroad, has the largest and most popular campground in the park and contains an outdoor amphitheatre, picnic areas, facilities for water sports and fishing, a canoe-rental concession and a campers' convenience store.

The parkway continues south from the Wapizagonke-north activity area, passing the eastern end of Lac du Caribou — a major departure point for back-country travel. Parking facilities here can accommodate 86 vehicles. The Lac du Caribou, Baie des Onze Îles, Baie Cobb, Lac Maréchal, Lac Tessier, Lac Webec, Lac Anticagamac, and Lac Wapizagonke system offers the finest opportunities for fishing and canoe-camping in the park. South of Lac du Caribou, the parkway rises again to the summit of a long ridge, west of Lac Wapizagonke, where two additional lookouts — Le Vide Bouteille and Île aux Pins — offer spectacular views of the lake and the rolling woodlands to the east. Le Vide Bouteille — literally, "the empty bottle" — was named so because it overlooks a sandy point where, over the years, fishermen have stopped for a drink.

Near the southern limits of Lac Wapizagonke, visitors may enjoy the attractions of another major day-use area — Shewenegan. The park's most popular picnic-ground, Shewenegan offers a beach, hiking trails, canoe-rental facilities and a snack bar. It also is an important departure point for canoe-camping on Lac Wapizagonke. The first temporary interpretation centre at this site was formally opened to public use by Jean Chrétien, then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, on August 14, 1972.

Nearby is the Mistagance campground, which is accessible by road from the parkway. L'Esker, a picnic area at the southern extremity of Lac Wapizagonke, offers parking, water-sports facilities, and a boardwalk with interpretive panels over a bog area. La Clarière, a group camping area, is also nearby.

Before leaving the park at its southwestern corner, the motorist will pass another reception centre at the Saint Mathieu entrance, where he may obtain information about the park, register for fishing and canoe-camping excursions, obtain any permits he may require and sample the services of Info Nature, a co-operative association that sells nature books, posters and souvenirs. Since 1982, Info Nature has assisted Parks Canada in promoting the natural and cultural heritage of the park. Profits from its operations are used to further La Mauricie's recreation and interpretation programs.

Other Recreation Areas

In addition to the activity centres described in the foregoing paragraphs, many other sites have been developed for the use of visitors. Most are located on or near one of the numerous lakes in the park and are accessible from the parkway, by roads or trails leading from the parkway, or through the park's main water corridors. Many of these sites have picnic tables and facilities for landing canoes. Most provide opportunities for the canoeist, fisherman or visitor seeking holiday relaxation. Indeed, La Mauricie offers some of the finest opportunities in Canada for canoe-camping, an activity for which its unique terrain is ideally suited. Park authorities have made the development of back-country facilities to assist canoe-campers a high priority. Consequently, this form of summer recreation has proven very popular: Some 19,000 canoe-campers are welcomed in the park each year.

Aid to Senior Citizens

Park authorities have also taken special care to meet the recreation needs of senior citizens. Three lakes have been reserved for their exclusive use, and one other lake is open for use by the physically handicapped. Suitable docks or ramps have been installed at these lakes.

Park Trail System