A Brief History of Canada's National Parks

Chapter 2

Expansion in the West (1900 to 1981)

Introduction

The early popularity of Rocky Mountains Park and its principal vacation centre, Banff, was due in a large measure to the enterprise of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. For the first 25 years of its existence, the national park, later to become known as "Banff", was accessible only by railway. The company erected, with funds derived from sales of land, hotels at strategic points along its line through the Rocky and Selkirk Mountains. The company also carried on an advertising program that extolled not only the luxury of its hostelries, but also the magnificence of their surroundings. As visitor traffic increased, it was inevitable that Canadians would soon realize that a park area of 673 km2 would no longer serve the needs of a growing population. As events transpired, the demand for more and larger parks was met by the establishment of a chain of national areas that, midway into a new century, spanned the continent from the Atlantic almost to the Pacific Ocean.

As recorded in the first chapter of this history, park reserves or 'forest" parks had been established on the line of the Canadian Pacific Railway west of Banff at Lake Louise, Field and Glacier; at Waterton Lakes in the southwestern part of what is now Alberta; and at Jasper on the line of the projected Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. These reserves, together with Rocky Mountains Park, formed the nucleus of Canada's National Park system. By 1912, the motor vehicle, in various forms, was replacing the horse as a means of local transportation, and the pioneering instincts of early motorists exerted a profound influence on the expansion of the parks movement in Canada. In the following pages will be found details of the circumstances relating to the enlargement of the earlier park reserves, their confirmation as national parks, and the establishment of additional parks representative of the nation's outstanding scenic regions or its unique and varied wildlife.

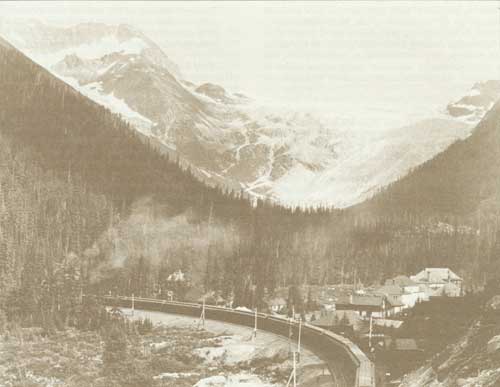

Glacier House Hotel and Station, Canadian Pacific Railways

Banff National Park

Before the close of the nineteenth century, the Government of Canada was urged to extend the boundaries of its national park. Early in January, 1899, A.E. Cross of Calgary, a member of the Legislative Assembly for the Northwest Territories, wrote the Honourable Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior, calling attention to the destruction of "big game" in the Territories. He suggested that Rocky Mountains Park be enlarged to incorporate lands between the Canadian Pacific Railway to the north and the Crows Nest Pass Railway to the south, extending easterly from the crest of the Rocky Mountains to the foothills. 1 Apparently Mr. Cross enlisted support for his proposal, for on February 25 Arthur L. Sifton of Calgary wrote to the Minister also recommending extension of the park boundaries. He enclosed a description of the lands he believed should form the extension, which lay south of Township 34 between the western boundary of Range 7 and the British Columbia boundary. 2

Howard Douglas, Superintendent of the park, had recommended an increase in the park area in his annual report for 1898. He now joined the advocates by forwarding a long letter to his Minister on March 23, 1899. Douglas compared the insignificant area of Rocky Mountains Park (673 km2) with that of Yellowstone National Park in the United States (7,770 km2) and the recently established Algonquin (1893) and Laurentides (1895) Provincial Parks in Ontario and Quebec, both of which exceeded 4,662 km2.3 He also drew attention to the attendance at Rocky Mountains Park for the years 1895 to 1898, which had greatly exceeded that at Yellowstone Park.

Another reason for suggesting an extension of boundaries was the possibility that, following the creation of provinces from the Northwest Territories, the assembly of land for park purposes might be more difficult. A final agreement advanced by Douglas was the need of ensuring that the park was large enough to accommodate visitors who might wish to ride out into wilderness areas and enjoy scenic and natural attractions not accessible by carriage roads.

The Park is Enlarged

Support from the press of western Canada also was evident, as editorials in the Winnipeg Free Press and the Vancouver World emphasized the need for immediate action. As the Free Press stated:

By all means let the National Park at Banff be enlarged, as the Superintendent urges in his annual report. Its area is about 260 square miles; about one-tenth the area of that of the United States National Park on the Yellowstone. There is lots of elbow room in the Northern Rockies as yet, and the time to take action is now — before vested interests shall have made it difficult to enlarge this, the most beautiful playground possessed by any people.4

Clifford Sifton approved the enlargement suggested by his brother Arthur and by Superintendent Douglas, and a bill to amend the Rocky Mountains Park Act was drawn and printed. The proposed legislation, however, was deferred until 1901, when the bill was resurrected and revised. The amendment was passed by Parliament during the 1902 session and received royal assent on May 15, 1902.5 The enlarged park now contained an area of 11,396 km2 including the spectacular Lake Louise area which had been originally reserved in 1892, together with the watersheds of the Bow, Red Deer, Kananaskis and Spray Rivers, and made available to park visitors the outstanding scenic areas surrounding the Bow, Spray and Kananaskis Lakes.

The area of Rocky Mountains Park later experienced further revisions. In 1908, the administration of the parks had been placed under the Superintendent of Forestry, and a forest and game protection service was organized. Howard Sibbald, who had been appointed chief game guardian of the park in 1909, recommended to Superintendent Douglas the deletion of a portion of the park comprising foothill country in which timber cutting and grazing privileges had been granted. Sibbald believed that boundaries where possible should be more definite than those described by township lines, many of which had not been surveyed. Douglas agreed that existing boundaries were impossible to locate on the ground and that the cost of a survey would be prohibitive. He also considered that any reductions should be compensated for by the addition of territory north of the park to the North Saskatchewan River. Superintendent Campbell of the Forestry Branch pointed out that the inclusion of the lands to the north would reduce the area outside the park open to public hunting and thus limit the area to which outfitters brought their hunting parties. Eventually, action was deferred on instructions from the Deputy Minister, who concluded that instead of dealing with Rocky Mountains Park in particular it would be better to consider the areas of all the parks along the eastern slope of the Rockies and adopt a consistent policy in each case.

A New Parks Act

On May 19, 1911, the Rocky Mountains Park Act was replaced by the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act, which incorporated in Rocky Mountain Forest Reserve all lands formerly constituting Rocky Mountains Park.6 The new act authorized the establishment and proclamation by Order in Council of Dominion Parks from lands comprising forest reserves. On June 8, 1911, Rocky Mountains Park was re-established, but with an area of 4,662 km2, or less than half its previous dimensions.7 Available records contain little information on why a reduction of 6,734 km2 was made, but presumably the reason was to bring the park area within the administrative capabilities of the existing park staff. There is also reason to believe that neither the Minister, the Honourable Frank Oliver, nor Superintendent Campbell of the Forestry Branch were sympathetic to the cause of park extension. This assumption is supported by the explanation offered for a drastic reduction in the area of Waterton Lakes Park, reviewed later in this chapter.

Soon after the new Parks Act came into force, the administration of the national parks passed from the Forestry Branch of the Interior to the recently-established Dominion Parks Branch headed by J.B. Harkin as Commissioner. The new commissioner recognized the need for a more equitable distribution of public lands set aside for the purposes of forest reserves and national parks. Discussions between officers of the rival branches of the Department led, in 1917, to the re-inclusion in Rocky Mountains Park of the upper Red Deer and Panther River watersheds, together with part of the Kananaskis River Valley. This extension increased the area of the park from 4,662 to 7,125 km2.8

More Boundary Changes

Within the next few years, the boundaries of Rocky Mountains Park again were changed. By 1927, the Government of Canada was committed to proceed with Acts of Parliament by which the natural resources in the four western provinces would be vested in the provincial governments. As lands contiguous to park boundaries would no longer be vested in the same government that controlled the parks, it was essential that future park boundaries be decided well in advance.

Early in 1927 a study of the boundaries of Banff and Jasper National Parks was authorized by the Deputy Minister of the Interior. R.W. Cautley, D.L.S., a departmental officer with wide experience, was detailed to investigate and report on suitable permanent boundaries for the two parks, with the co-operation of the provincial government.

L.C. Charlesworth, Chairman of the Irrigation Council of Alberta, was appointed official representative of that province. Mr. Cautley travelled extensively during the summers of 1927 and 1928. His report recommended deletion of certain areas which had more value to the province by reason of their commercial possibilities, and the retention of areas which had outstanding park characteristics and potential. All recommendations had the unqualified approval of the provincial representative and, as a preliminary step, an area of 2,528 km2 south of Sunwapta Pass, which had formed part of Jasper National Park, was transferred to Rocky Mountains Park on February 6, 1929. At the same time an area of 267 km2 surrounding Mount Malloch was added to the park. These additions increased the area of the park to 9,920 km2.9

The withdrawal from Banff National Park of lands which failed to meet the new criteria was accomplished by the National Parks Act in 1930.10 Among the areas deleted were the Kananaskis River Valley which had been badly scarred by fire; a portion of the Spray Lakes watershed which had water-power potential; an area in the Ghost River watershed; much of the Red Deer River watershed; and an area of 976 km2 in the angle of the Cline and Siffleur Rivers which had been included in the transfer from Jasper to Banff Park in 1929. The 1930 Act established the name of the park as "Banff" and its area as 6,695 km2.

The name "Banff" came into use in 1888, when the railway station was moved from its original site at "Siding 29" to a permanent one adjoining the park townsite. In turn, the townsite took the name of the station. The name was suggested by Sir Donald Smith, later Lord Strathcona. A director of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, Smith was born near Banff, a town in northeastern Scotland.

Latest Adjustment in Area

A minor adjustment to the eastern boundary in 1933 followed the transfer to Canada by Alberta of 84 ha to facilitate the construction of a new park entrance building on the Calgary-Banff Highway. The latest revision in the Park boundaries occurred in 1949 when adjustments were made in the vicinity of the Spray Lakes reservoir which had been developed by the Calgary Power Company.11 At the request of the Province of Alberta, 54 km2 in the vicinity of Goat Range were withdrawn by an amendment to the National Parks Act. This withdrawal facilitated the completion of a hydro-electric power development on provincial land, and left Banff National Park with an area of 6,641 km2.

The Automobile Arrives

The automobile was responsible, more than any other factor, for the expansion of visitor services in Banff and subsequent national parks. Although barred from park roads by regulation until 1910, the now ubiquitous "car" rapidly attained popularity and influenced the development of an extensive inter-park highway system. By 1911, Rocky Mountains Park was accessible from Calgary by road and the extension of a motor route westerly from Banff was undertaken that year. By 1920 a connection with Lake Louise was made, and access to Banff from southeastern British Columbia was made possible by the completion of the Banff-Windermere Road in 1923. An extension of the road from Lake Louise to Field in 1926 permitted motor travel to Yoho Park, and the following year the Kicking Horse Trail to Golden was opened.

The depression years of the "thirties" gave rise to a new motor road. Construction of the Banff-Jasper Highway was undertaken in 1932 as an unemployment relief project and was completed in 1939. Its opening, early in 1940, resulted in a direct motor route between Lake Louise and the Townsite of Jasper, traversing a magnificent scenic region replete with snow-crowned peaks, waterfalls, icefields and glaciers.

Successive improvements to the main highway through Banff and Yoho Parks were climaxed by the construction of the Trans-Canada Highway. The route, selected after intensive surveys, by-passed much of the original road construction. Completion of the highway through Banff Park in 1958 resulted in a greatly increased volume of visitor travel.

Original Upper Hot Springs, Banff, 1930

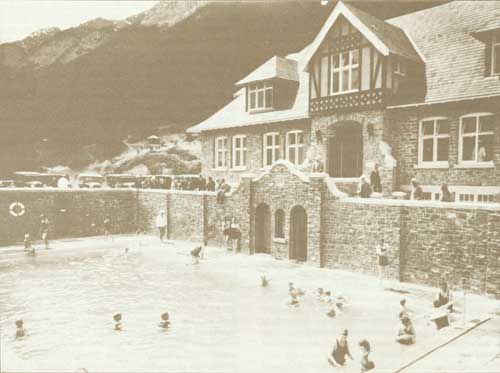

New Upper Hot Springs, Banff, 1932

Improvements at Banff

Increased public use of Rocky Mountains Park led to the expansion of the Townsite of Banff and the development of additional visitor accommodation and services. Horse-drawn vehicles, including the picturesque tally-ho, were discarded for buses and taxis. Several of the early hotels in Banff gave way to modern structures. Both the historic Banff Springs Hotel and the Chateau Lake Louise emerged in new form from the ashes of earlier construction devastated by fires.

The development of bungalow cabin camps in Banff National Park began in 1934, when sites for this form of visitor accommodation were advertised by the Park Superintendent. Located on the outskirts of Banff Townsite and along park highways, these innovations enjoyed a good patronage. In turn, the cabin developments later were supplanted by motels and motor hotels, constructed mainly in the Townsite of Banff. By the mid 1960's, motel accommodation had largely replaced other forms of public accommodation.

Development of the first visitor services centre outside a park townsite was undertaken at Lake Louise Station in 1964. This innovation, which concentrated in one area a public campground, trailer park, picnic area and modern motel accommodation, permitted the Department to ban future ribbon development of visitor services along park highways.

Hot Springs Development

Banff's mineral hot springs continued to hold their attraction for visitors. The original bathing establishments at the Upper Hot Springs operated by private enterprise were supplemented in 1904 when a new outdoor pool and a bath-house were constructed by the park administration. The bath-house contained not only dressing-rooms for men and women but also hot plunge baths, steam rooms, hot and cold showers and modern lavatories. Its popularity soon necessitated extensions to provide essential dressing-room accommodation.

Eventually this public facility became outdated and below the standard befitting a national park. In October, 1931, the site of the former Grandview Villa hotel, which had been damaged by fire earlier that year, was acquired from the Brett family for $6,500. Here construction of a new stone bath-house and outdoor pool was undertaken. Completed and opened in June, 1932, the new building incorporated many desirable features including indoor plunges, steam rooms and commodious dressing rooms and was operated the year round. A program of modernization carried out in 1961 resulted in a new bathing pool, improved access to interior services, and provision for coffee shop and massage concessions.

Cave and Basin Springs

By the turn of the century, the Cave and Basin bathing pools were no longer capable of accommodating the number of patrons wishing to use them. Late in 1902, Park Superintendent Douglas commenced construction of a new pool, which was completed and opened for use in 1904. It measured 15 by 30 m, had a maximum depth of 2.7 m, and was complemented by additional dressing-rooms built that year and in 1905. Eventually, existing facilities became inadequate and, in 1912, excavation for a large new bathing establishment, designed by Walter Painter, a Calgary architect, was commenced. Difficulties in its construction delayed the opening of the new structure until 1914. Much of the superstructure was erected on piles driven into the porous underground tufa. Walls of the building and the pool were constructed of concrete, and exterior walls were faced with Rundle limestone. Two belvederes at the eastern end, capped with red tiles, formed a striking feature of the design. One gave access to the cave, and both provided vantage points from which spectators could view the swimming area. The roof over the dressing-rooms located along the south side of the pool also formed a promenade and viewpoint. With dimensions of 41 by 11 m, the new pool was believed to be the largest in Canada.

Later Reconstruction

Substantial renovation was undertaken at the Cave and Basin bath-house in 1935, during which the wooden dressing-rooms erected in 1887-1903 were demolished and replaced by a new structure faced with stone. The basin hot pool also was upgraded, a wading pool developed, and improved access to dressing-rooms was provided. Original construction of the dressing-rooms' roof had employed glass panel pavers, the joints of which leaked. Natural diffused light beneath was cut off when the roof had to be repaired by overall tarring. Hot spring waters heavily impregnated with minerals caused a severe plumbing problem, particularly after chlorine was introduced for sanitary reasons. Water in the large pool presented a heavy murkiness that resulted in a fatal accident when lifeguards were unable to observe a bather in distress. Consequently, in 1960 the natural spring water in the pool was replaced with chlorinated water from the townsite water system, artificially heated to maintain a comfortable temperature. In 1970, it was found necessary, for sanitary reasons, to close the Basin "hot" pool and the adjoining wading pool. In 1980, the indoor hot plunge baths also were closed.

Plans for Centennial

By the mid-1970's, planning for the celebration of the National Parks Centennial in 1985 had begun. The Cave and Basin springs, regarded as the "birthplace" of our national park system, obviously would occupy a very important place in objective planning. However, by 1976, a deteriorated building, serious maintenance problems, and costs of operation had prompted the closing of the Cave and Basin bath-house. Early planning proposals favored permanent closing of all bathing facilities and the use of the bath-house as an interpretation centre. Residents of Banff and vicinity, however, objected strongly to this proposal, and a local committee dedicated to the retention of the Cave and Basin bath-house as an active recreational centre was formed. It sponsored petitions that eventually collected several thousand signatures advocating the preservation of the Cave and Basin in its original state.

Reconstruction Decided On

Reconstruction of earlier proposals by Parks Canada, coupled with public consultation, resulted in the receipt of several concepts for future use of the historic establishment. Eventually, a proposal combining an outdoor swimming pool with an interpretation centre was chosen. The future Cave and Basin Centennial Centre as proposed would provide year round activity. During a summer season of some 80 days, swimmers clad in their own bathing attire, or alternatively in 1914 style rental suits, would be able to use the large open-air pool filled with chlorinated and filtered water from the thermal spring in the Cave. Provision of modern change-rooms on the ground floor of the 1914 "longhouse" would include facilities for the handicapped. Also, the end of the reconstructed pool would rise to zero depth, permitting its use by the very young and by persons in wheel chairs.

The restoration concept would present the Basin pool in its 19th-century appearance, with a replica of its 1887 bath-house on its margin. However, because of present-day sanitary and safety standards, the Basin spring would not be available for bathing. The Cave would be featured, and the second floor of the longhouse portion of the building would exhibit lively items commemorating the history of Canada's national parks. The bath-house also would incorporate a photo-gallery, an Edwardian lounge, and a small theatre providing multi-image audio-visual programs recalling outstanding events which occurred in Canada's national park system during the preceding 100 years.

Reconstruction of the Cave and Basin bathing establishment began in 1981 and was carried on to its completion early in 1985. In addition to restoration of the pool and other components of the building as outlined above, the tunnel leading to the Cave was made accessible to wheel chairs. Interpretation facilities at the Centennial Centre are open year round, a large parking lot was completed, and two interpretive walking trails constructed. The Discovery Trail highlights the history and geology of the hot springs, and the Marsh Trail focuses attention on the plant and animal life associated with warm sulphur water.

On June 15, 1985, the restored Cave and Basin Centennial Centre in Banff National Park was formally opened by the Minister of the Environment, Hon. Suzanne Blais-Grenier, in the presence of several hundred guests and other park-minded visitors assembled for this tribute to the completion of 100 years of national parks in Canada.

Campground Extension

The provision of campgrounds was a logical sequence to the development of motor travel. The first major campground in the park was laid out along the Bow River in 1916, below its confluence with the Spray. Later, when the site was required for an extension of the Banff Springs golf course, a new campground was developed on Tunnel Mountain in 1927. It was expanded gradually to accommodate both trailer and tent accommodation. A continuing demand for camp sites influenced the development in 1967 of a new campground east of the original one on Tunnel Mountain. By 1969 the expanded campground — the largest in the national park system — provided the ultimate in camping amenities including water, sewer and electric power services. Two additional serviced campgrounds, together with nine satellite areas, provided additional sites for camping parties.

Winter Sports Activity

The transformation of Banff National Park from a summer vacation area to a year-round resort followed the expansion of winter sport activities. An annual winter carnival was carried on at Banff for more than 50 years. Curling was organized in 1900 and a local club built its first closed rink in 1922. Its base of operations was relocated in 1962 following the completion of the Banff Recreational Centre.

Skiing was introduced in 1900 and gradually through the years attained a fantastic popularity. Early ski developments were concentrated on the slopes of Mount Norquay overlooking the town of Banff, where a local club erected a club-house and the Park Superintendent co-operated in the development of a jumping hill and down-hill runs. The first chair lift, which doubled in summer as a sight-seeing conveyance, was installed in 1948. Development of a ski centre on Mount Whitehorn near Lake Louise was undertaken in 1959 when a gondola lift was constructed by private enterprise on the lower slopes of the mountain. This installation later was augmented by several lifts. New down-hill runs were developed and a large parking area was constructed. The nucleus of another popular ski centre northwest of Banff at Sunshine Valley was built in 1936. Early tows and lifts were improved in 1956, and in 1963 a major redevelopment of the area was undertaken by private enterprise. New installations including three chalets providing overnight accommodation, a day lodge, T-Bar tows and chair lifts all contributed to the development of Sunshine Village as a major ski resort.

Cultural amenities in Banff were broadened following the construction of the Banff School of Fine Arts between 1947 and 1968. This extensive complex, located on the slopes of Tunnel Mountain overlooking Banff, was sponsored and constructed as an extension to the University of Calgary. It offers a variety of courses in fine arts, music, languages, and business management. The erection of a modern building in 1968 within the town of Banff to house the Archives of the Canadian Rockies provided local citizens and visitors with a modern library, an art gallery, and a repository for papers, books, records and artifacts relating to the Canadian Rockies.

As the oldest, one of the largest, and the best known of Canada's National Parks, Banff has maintained its early popularity. Its magnificent scenery, excellent highways, unique natural attractions and its man-made amenities have attracted visitors in increasing thousands during its 85 years of existence. Each year since 1967, more than two million visitors have enjoyed unique and diversified attractions confirming the prediction of one of its original sponsors, Sir John A. Macdonald, that it would become "a great watering-place".12

Endnotes

1. National Parks Branch File B.2, vol. 1, 21 Jan. 1899.

2. Ibid., Feb. 25, 1899.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Statutes of Canada, 2 Edward VII, chap. 31.

6. Statutes of Canada, 1-2 George V, chap. 10.

7. Order in Council P.C. 1338, June 8, 1911.

8. Order in Council P.C. 2594, Sept. 18, 1917.

9. Order in Council P.C. 158, Feb. 6, 1929.

10. Statutes of Canada, 20-21 George V, chap. 33.

11. Statutes of Canada, George VI, chap. 5.

12. Canada, House of Commons, Debates, May 3, 1887.

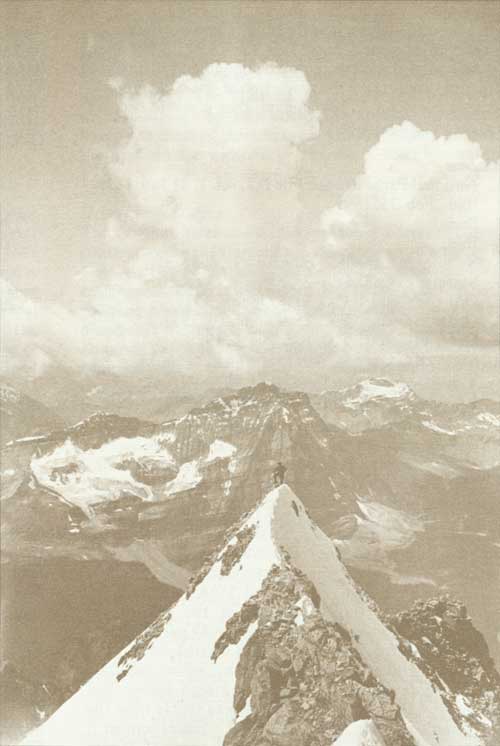

Mount Lefroy, Banff National Park

Guide Rudolph Aemmer on the summit of Mount Victoria, Banff National Park, 1933

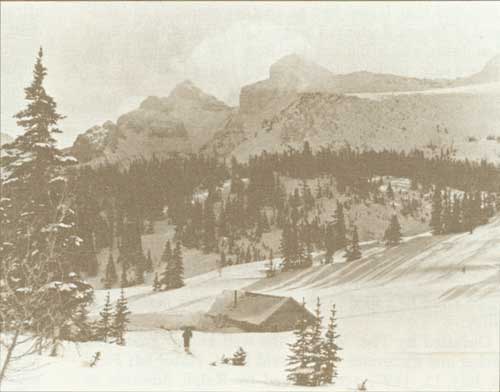

Sunshine Pass, Banff National Park

Yoho National Park

The national park movement gathered considerable momentum in December 1901, when the park reserve around Mt. Stephen in British Columbia was enlarged to incorporate an area of 2,144 km2.1 Described as the Yoho Park Reserve, it included the spectacular Yoho Valley, Emerald Lake, Lakes O'Hara and McArthur, and the major portion of the watersheds of the Beaverfoot, Ottertail, and Amiskwi Rivers. This timely park development stemmed from the explorations carried out in 1897 by Dr. Jean Habel of Berlin, Germany, whose ambition was to explore the area surrounding a high glacier-clad peak beyond the Yoho Valley which was visible from the line of the Canadian Pacific Railway.2 Habel termed it "Hidden Mountain". It was given the name of Mount Habel in 1898, but later was changed by the Geographic Board of Canada to "des Poilus" commemorating the French soldier in the First Great War.3 In his interesting book "The Trail to the Charmed Land", Ralph Edwards contended that Habel had as another objective the conquest of Mount Balfour. This peak dominated the Wapiti Mountains which flanked the Bow River Valley on its western side, northerly from Kicking Horse Pass.4

Yoho Valley Explored

A professor of mathematics, a scientist and mountain climber of considerable skill, Doctor Habel arrived at Field in June, 1897. Attempts to reach and climb Mt. Balfour had been made from the Bow River Valley on the eastern side. Habel was informed that the valley of the Yoho River, or north fork of the Wapta River as it was then known, was impenetrable — a tangled wilderness of canyon, rocks and trees.5 Undaunted, Habel decided to approach his objective by way of Emerald Lake, from which point he hoped to reach the reputedly inaccessible valley.

Outfitted by Tom Wilson, the well known guide and packer and discoverer of Emerald Lake, Habel left Field on July 15, 1897, accompanied by Ralph Edwards as guide, Fred Stephens as chief packer and Frank Wellman as cook.6 The outfit was carried by four horses but Habel chose to travel on foot. Emerald Lake was accessible by trail but from then on the route lay through primitive forests and across glaciated slopes. Making their way over Yoho Pass the party reached a point where the glacier-hung walls of the spectacular Yoho Valley and the glittering cascade of Takakkaw Falls met the eyes. As Habel described the scene:

The torrent from the hanging glaciers, which cover the eastern terraces of the valley, descended directly opposite to us in a very powerful waterfall. Rushing from under the ice at about the height of our standpoint, this fall plunges over a nearly perpendicular wall down to the very level of the valley bottom in beauty and grandeur hardly to be excelled by any other on our globe. An entire view of the falls can only be got from a point like that at which we stood, and not from the lower parts of the valley.7

Working their way down to the floor of the valley the party explored the upper Yoho or "Waterfall" valley, Twin Falls, Yoho Glacier and the Waputik Icefield. Habel was able to climb an outrider of Mount Balfour which he named "Trolltinder" but was obliged to cut short his exploration and any attempt to climb "Hidden" Mountain when supplies ran low. A return was made to the Kicking Horse valley and Field by travelling along the floor of the Yoho Valley to the canyon, which was avoided by a climb up the forested slopes around the northwestern side of Mount Field.

Park Reserve Established

A description of Habel's travels was read to members of the Appalachian Mountain Club at its annual meeting in 1898, but it was not until 1901 that the remarkable scenic attractions of the area were brought to the attention of the Department of the Interior at Ottawa. Ralph Edwards, Habel's guide, had described the Yoho Valley and its wonders to his employer, Tom Wilson. In turn Wilson was able to impress officers of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company with the possibilities of the region as a tourist attraction, provided it was opened up by construction of a road. Eventually, in February 1901, Charles Drinkwater, assistant to the president of the railway company, described Habel's discoveries to James A. Smart, Deputy Minister of the Interior, during a visit to Ottawa. Drinkwater followed up his interview with a letter to Smart and recommended that the Yoho Valley be set aside as a park reserve. Obviously impressed with the tourist possibilities of the recent discoveries, Drinkwater also made a formal application for a grant of an area of 9.3 ha near the railway station at Field, on which the railway company proposed to construct stables, a corral and other improvements that might be required to serve the visitors that would be attracted by the scenic wonders that had been disclosed.8

After considerable deliberation, during which the name "Wapta Falls" was considered and discarded, the "Yoho Park Reserve", containing 2,146 km2, was established on December 14, 1901, to preserve the "glaciers, large waterfalls and other wonderful and beautiful scenery within its boundaries". Attached to the enacting Order in Council was a plan which outlined in red the boundaries of the reserve. The name "Yoho" was suggested by the Surveyor General, Edward Deville, who, in a memorandum to the Deputy Minister, observed that the correct name of the principal waterfall was "Takakkaw" which had been selected by Sir William Van Horne, Chairman of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. At the time, Mr. Deville observed that the name "Takakkaw" was the Cree Indian for "it is magnificent".9

Yoho Becomes a Park

In 1911, the Yoho Park Reserve was re-established under authority of the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act as Yoho Dominion (National) Park.10 In common with several other park reserves established at the same time, it suffered a reduction in area to 1,450 km2. Eleven years later, a further reduction was made to eliminate several timber berths from the park. This withdrawal reduced the park area to 1,233 km2. Concurrently with the passing of the National Parks Act in 1930, the park boundaries again were adjusted to follow, as far as possible, heights of land, rather than township lines, and increased the park's area to l,313 km2.

Park Development Commenced

Development of the enlarged park reserve was undertaken by the Department of the Interior shortly after its establishment. From 1902 until 1908 its administration was supervised by Howard Douglas, Superintendent of Rocky Mountains Park, with the help of an assistant superintendent. After 1908, the local administration of the park was carried out by a resident superintendent. Douglas undertook construction of a network of roads including one to Emerald Lake which was completed in 1904. The task of opening up Yoho Valley was commenced in 1903 but limited funds, rugged terrain, and primitive equipment all combined to extend the construction period to seven years. By 1909, Takakkaw Falls were accessible by horse-drawn carriages and the following year the road was completed.11 Douglas also built a diversion in the Emerald Lake road to provide access to the natural bridge over the Kicking Horse River west of Field and converted an abandoned railway grade leading westerly from Field to Ottertail to a carriage road.

Following construction by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company in 1908-09 of the spiral tunnels in Mounts Ogden and Cathedral, which reduced the grade of the "big hill" east of Field, Superintendent Douglas utilized the abandoned railway right of way to construct a scenic drive easterly up Kicking Horse River Valley almost to Wapta Lake. Most of the roads previously used by horse-drawn vehicles were opened to motorists in 1919, and the Yoho Valley Road was made accessible to automobiles in 1920.12 Public demand for a motor route to Yoho Park from Lake Louise led the Department of the Interior in 1924 to commence construction of a road to Field, together with an extension from Field to the western boundary of the park. The section to Field was completed and opened to travel in July, 1926. By the end of that year construction had been carried to the park boundary, where it linked with a road constructed by the Province of British Columbia from Golden. The combined route, known as the Kicking Horse Trail, was formally opened to traffic in July, 1927. The main highway through the parks served as a link in a transcontinental motor route from the Prairies to British Columbia, until the Trans-Canada Highway project was instituted. Over the years, other roads in the park were improved. The Emerald Lake road was relocated in places in 1959 and paved in 1962. The Yoho Valley road also has been given a "face-lifting" by relocation. The spectacular. switch-backs lost most of their hazards to timid motorists when the grades were widened by the use of steel bin-wall in 1956.

Hotels and Lodges

The original hotel at Field, the Mount Stephen House, constructed by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company in 1886, served as the principal visitor accommodation for many years. Later it was turned over to the Y.M.C.A. as a rooming house and recreational centre for railway employees. It was finally demolished in 1963 after staff was accommodated in a modern bunk-house. Additional accommodation in the form of lodges and bungalow camps was constructed by the railway company at Emerald Lake in 1903 and at Yoho Valley, Wapta Lake, and Lake O'Hara in the "nineteen-twenties" but gradually these concessions were sold to individual operators. Cathedral Mountain Chalets were built in 1933 near the junction of the Yoho Valley Road and the Trans-Canada Highway. Wapta Lodge was gutted by fire in 1961 and was rebuilt in 1963 as a modern motor hotel by a Calgary group.

Park Administration

Although Yoho National Park was placed in charge of a resident superintendent in 1908, the duties of the latter were expanded some years later to take in the administration of the three other parks in British Columbia — Kootenay, Glacier and Mount Revelstoke. In 1957, Glacier and Mount Revelstoke parks were placed under separate administration, and an individual superintendent was assigned to Kootenay Park. The first park office was built in 1905 on railway land near the telegraph office at Field. In 1933, the superintendent and staff moved to a building on Stephen Avenue, formerly occupied by a bank. Later the lot and building were acquired by the Department, and in 1955 the premises were enlarged and modernized.

The Townsite of Field dates from 1884, when construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway reached its site. It was named after Cyrus W. Field, promoter of the first Atlantic cable, who was in the vicinity that year. 13 Early residents lived on both sides of the Kicking Horse River, but houses on the north side were almost totally destroyed or impaired by an avalanche which occurred in 1909 on the slopes of Mount Burgess. The present townsite was first surveyed in 1904, after which a number of additions were made. Field has the distinction of being the only townsite in a national park in which all lots are not leased to residents by the National Parks Administration. After the railway was completed, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company surveyed part of its station grounds as a subdivision, and a portion of the townsite north of Stephen Avenue still remains under railway control and ownership.

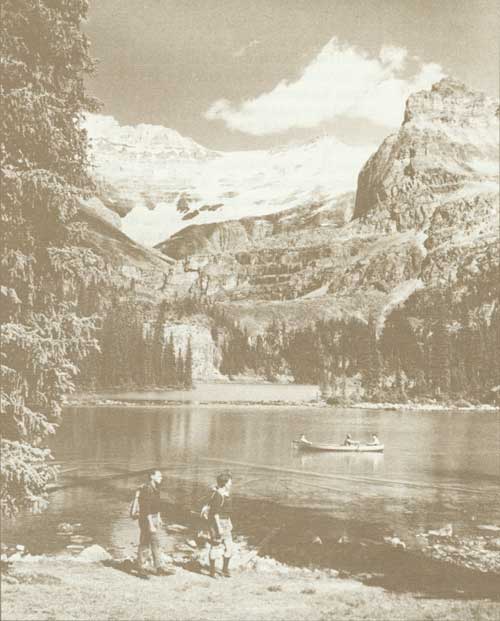

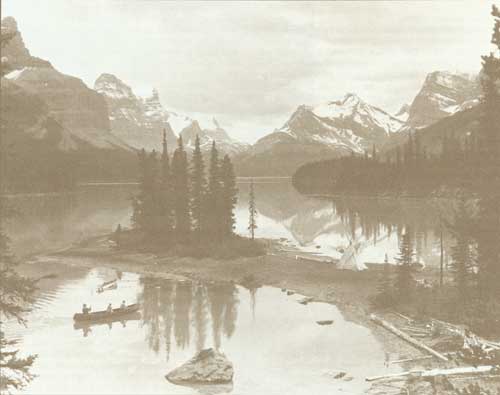

Lake O'Hara, Yoho National Park

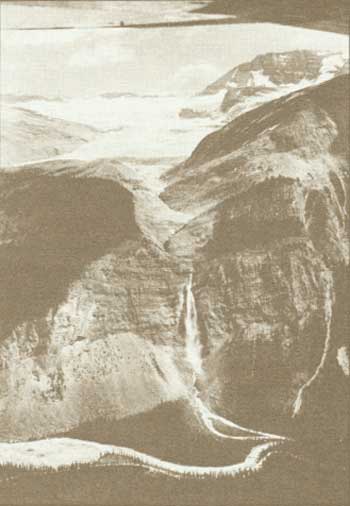

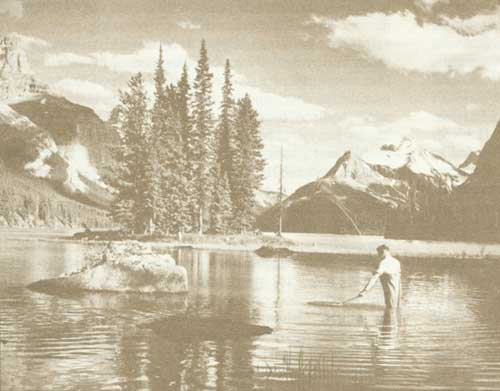

Daly Glacier and Takakkaw Falls, Yoho National Park

Highway Access Improved

Prior to 1926, access to the park from distant points was possible only by railway. Most of the early visitors disembarked from the trains at Field, where they were accommodated at the Mount Stephen House or driven by tally-ho to Emerald Lake or to other available accommodation. Early visitors to Wapta Lodge and Lake O'Hara Lodge had the option of leaving the train at Hector Station overlooking Wapta Lake. From this point they reached their destinations by boat to Wapta Lodge or by riding trail to Lake O'Hara.

The completion of the main park highway, the Kicking Horse Trail, from the eastern to the western boundaries of the park in 1927 opened a highly scenic route to motorists and in a few years the largest proportion of visitors to Yoho Park arrived by motor vehicle. In turn, this motor traffic stimulated a demand for campgrounds and picnic sites which were developed by the National Parks Service at strategic points along the principal avenues of travel. Construction of the Trans-Canada Highway through the park began in 1955 and was carried on for the next three years. By the end of 1958, the highway had been completed and hard-surfaced with the exception of a final lift of asphalt which was laid in 1963. The opening of the Trans-Canada Highway over Rogers Pass and through Glacier and Mount Revelstoke National Parks in 1962 helped swell the tide of visitors, which in Yoho Park now exceeds 900,000 each year.

Recreation

Outdoor recreation enjoyed by residents of and visitors to the park included riding, hiking and mountain climbing. Horse liveries were operated at Field and Emerald Lake in the early days of the park existence and at Yoho Valley and Wapta Lodge following their opening in the early 20's. The Alpine Club of Canada held its first camp in the park in 1906. For many years it held a lease covering the site of a summer camp on the south shore of Lake O'Hara. In 1931, the club was granted the occupancy of the two cabins left in the Alpine Meadow after the balance of the C.P.R. buildings comprising Lake O'Hara Lodge were moved to the lakeshore in 1925 and 1926. The club erected a lodge in the little Yoho Valley in 1941. The area between Yoho Valley and Emerald Lake has been a popular one for hiking and riding, and trails used extensively include those crossing Yoho Pass and along the upper slopes of the President Range overlooking Takakkaw Falls. A nine-hole golf course was built on the Kicking Horse flats in the mid 1930's, and was used by residents for some years. A ski hill was developed by the Field Recreation Commission on a slope cleared west of Field on the Trans-Canada Highway. A curling club, formed at Field in the early 1930's, has continued operation, and skating on an outdoor rink has been popular for years.

The Monarch Mine

Openings on the steep faces of Mount Stephen and Mount Field on opposite sides of the Kicking Horse River bear witness to a mining operation carried on east of Field for nearly sixty years.

The Monarch claim was located in 1884 on information supplied by Tom Wilson and was Crown granted in 1893. Hand-sorted shipments of lead ore were shipped intermittently to Vancouver until 1912, when a small gravity-type concentrator was erected by the Mount Stephen mining syndicate on railway land below the mine opening. Milling began that year and was continued off and on until 1924. In 1925, the Monarch mine, together with the adjoining St. Etienne and other claims on Mount Stephen as well as a group of claims across the valley known as the Kicking Horse Mine, were acquired by A.B. Trites, president of the Pacific Mining Development and Petroleum Company. Trites obtained a licence of occupation in 1926 for three parcels of land in Kicking Horse Valley from the Minister of the Interior for works and buildings. He also entered into an agreement which granted the Company certain privileges. In return, the agreement provided that at the end of the 21-year term, title to all Crown-granted and other mineral claims held by Trites and his company would revert to the Crown in right of Canada.

In 1929, Trites sold his interest in the two mines to Base Metals Mining Corporation. The Corporation built a new mill below the Monarch claim on railway land, installed an aerial tramway, erected accessory buildings and commenced operations in November, 1929. The Kicking Horse Mine, which included claims first located in 1910, was brought into production in 1941. The installation of an aerial tramway permitted the conveyance of ore from the mine portal to a bin on the valley floor, from which it was trucked a distance of three kilometres to the mill below Mount Stephen.

During the war years, production of lead, zinc and silver reached a high level and in 1947 the corporation requested and was granted an extension of two years in which to remove all remaining minerals. In 1948 the term of the licence was extended to 1957 but by November, 1952, the corporation had closed both mines. During the next two years it disposed of much of its mining equipment. With Departmental consent, the corporation sub leased a number of its buildings to contractors engaged on the Trans-Canada Highway and to the federal Department of Public Works. Early in 1958, the Company agreed to convey title to the Crown covering all claims which it then held. Acceptance of a surrender from the Company of its interests was delayed until the lands formerly occupied had been cleaned up and the portals to the mines had been sealed to the satisfaction of the park superintendent.

During the periods of operation a large heap of mine tailings had been dumped on the bank of the Kicking Horse River, creating an unsightly deposit and, in dry weather, clouds of dust in the vicinity. The unsightly piles of tailings were eliminated in July, 1960, during a period of high water, when they were bull-dozed by park forces into the Kicking Horse River. The former mining camp had been cleared by 1961 but compliance with the portal sealing requirement had not been obtained by the Department in 1968, in spite of correspondence and negotiations carried on for ten years. Finally, in May, 1968, the corporation completed a conveyance of title covering its land and mineral holdings to the Crown in right of Canada.

Endnotes

1. Order in Council P.C. 1901-2181, Dec. 14, 1901.

2. Jean Habel, The North Fork of the Wapta, Appalachia, vol. V III, 1898.

3. Geographic Board of Canada, "Eighteenth Report" (Ottawa: King's Printer, 1924).

4. Ralph Edwards, The Trail to the Charmed Land (Saskatoon: H.R. Larson Co., 1950).

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Habel. See above, note 2.

8. National Parks Branch File Y.2, Feb. 18, 1901.

9. Ibid., Nov. 26, 1901.

10. Order in Council P.C. 1911-1338, June 8, 1911.

11. Department of the Interior, "Annual Report", 1911, part V, p. 37.

12. Department of the Interior, "Annual Report", 1921, p. 38.

13. Geographic Board of Canada. See above, note 3.

Glacier National Park

For more than fifteen years after its establishment in 1886, the mountain park reservation around Glacier Station in the Selkirk Mountains remained relatively undeveloped by the federal Government. Located in the heart of a rugged alpine wonderland, it was accessible only by the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The route across the mountains lay over Rogers Pass, down the precipitous sides of which thundered avalanches carrying before them rocks, trees, ice and snow. Protection to railway cars and passengers was provided by lines of snow sheds and glances, built of heavy timber and capable of diverting or sustaining the great masses of snow and debris that rolled down during the winter months.

Glacier House and Station

Near the summit of the pass, the railway company had established at Rogers Pass Station a maintenance headquarters including a round-house where extra locomotives, snow plows and other equipment were stored. A small settlement developed along the right of way, which eventually was surveyed by N.C. Stewart, D.L.S., in 1912 as Rogers Pass Townsite. This small subdivision accommodated the dwellings of railway employees, a boarding house, store, a post office and a recreation hall. At Glacier Station, 4.8 km to the west, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company had constructed in 1886 a restaurant and small hotel known as Glacier House. This was one of four mountain hotels developed by the Canadian Pacific Railway to facilitate the hauling of trains up the heavy mountain grades. As explained by J.M. Gibbon in his history of the Canadian Pacific Railway:

There is no hotel so expensive to operate as a dining car on wheels, the labour on which doubles the primary cost of the meals, and as the train carried passengers of every class and purse, station restaurants had to be built as suitable places in the mountain districts, lessening the number of dining cars to be hauled and providing the initial cost of a tourist hotel.1

Alpine Centre

Similar developments had been installed at Field, Revelstoke and North Bend, all in British Columbia.

Glacier House opened for business on January 1, 1887, and very soon its unique location, magnificent setting, and its excellent service began to attract visitors, especially those with the resources and leisure to frequent alpine areas. One of the principal attractions of the area was the immense variety of mountains which offered unlimited scope to mountain climbers. Ascents in the vicinity of Rogers Pass had been made by its discoverer, Major A.B. Rogers, and his nephew in 1881, as well as by Professor John Macoun and his son James.2

In 1888, the Reverend W.S. Green of the British Alpine Club inaugurated what might be termed the "climbing era" in the Selkirks. Green undertook the task of mapping the peaks and glaciers surrounding Rogers Pass and in 1890 published an account of his climbs in his descriptive book, "Among the Selkirk Glaciers".3 That year, members of the English and Swiss Alpine Clubs visited the area and achieved a number of notable ascents, including that of Mount Sir Donald, formerly Syndicate Peak, which was accomplished by Emil Huber and Carl Sulzer. In 1897, a party of British climbers including Professor J.N. Collie, H.B. Dixon, and J.P. Baker brought out the first Swiss guide, Peter Sarbach.4 Two years later the Canadian Pacific Railway imported two accredited guides from Interlaken, Switzerland, Edouard Feuz and Christian Hasler, the first of a colony of guides who served an enthusiastic clientele over the years at Lake Louise, Field and Glacier. A steady increase in visitors necessitated two extensions to Glacier House Hotel, the second of which was made in 1906 and brought the accommodation up to 90 rooms.5

In its original form, the park reservation at Glacier comprised a rectangular area about 10.5 km long by 7 km wide. It enclosed Rogers Pass, the railway loop below Glacier Station, Mounts Macdonald and Avalanche, and the tongue of Illecillewaet Glacier. Oddly, it did not include Syndicate Peak, later named Mount Sir Donald, although the order in council which first authorized the reservation specifically mentioned it.6 Early improvements carried out in the vicinity of Glacier House consisted mainly of walking trails constructed by the Railway Company, which provided access to the Illecillewaet, or "Great" Glacier, Marion Lake on the slopes of Mount Abbott, and other nearby points. By 1903, Glacier House was a well established alpine centre and a great many of the mountains in the vicinity had been climbed. A table of first and second ascents of some of the higher peaks in the reserve, compiled by A.O. Wheeler, indicated that by the end of 1903 nearly 40 major mountains or crests had been climbed for the first time.7

Glacier Park Enlarged

On November 26, 1903, Glacier Park reserve was enlarged to include sixteen townships or 1,492 km2.8 The order in council did not elaborate the reason beyond stating "it is now desirable to enlarge its boundaries so as to include the best scenery in the neighbourhood". There seems little doubt, however, that the Minister of the Interior acceded to popular demand that a larger area of outstanding alpine scenery be set aside for public use. Following the enactment of the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act in 1911, reductions were made in the areas of several national parks. Glacier Park was reduced by 280 km2 to 1,212 km2, in order to eliminate lands considered unsuitable for park purposes.9 In 1930, new boundaries following heights of land were established, and the resulting area of the park was 1,349 km2.10

Nakimu Caves Discovered

The discovery of the Nakimu Caves in 1904, by C.H. Deutschman of Revelstoke, attracted additional attention to Glacier Park and resulted in the first active development of the park by the Government. Although born in the United States, Deutschman was a naturalized Canadian citizen. He made his remarkable find while prospecting in the vicinity of Cougar Creek. Earlier in the year, Deutschman had visited the area on snow-shoes but was unable to make progress in the deep soft snow. In October, he returned and, while following the creek up the valley, suddenly realized that the creek bed had gone dry.

I could hear the water rushing ahead of me and when I investigated, I found that the stream disappeared into the ground through a large hole at the bottom of the big falls. Nearby, I found another large opening in the rock and went into it as far as daylight permitted. Through later explorations, I was to learn that I had that day, October 22, 1904, discovered the largest system of caves in Canada. I spent the next few days hunting for more entrances to the caverns and located a total of seven, some large and others just big enough for me to squeeze through.11

Deutschman consolidated his find by staking two mineral claims covering an area of 914 by 457 m, and recorded them at Revelstoke. In April, 1905, Deutschman escorted his first visitor, the editor of the Revelstoke Mail-Herald, A. Johnston, through the caves. In May, he returned with a party of twelve including Howard Douglas, Superintendent of Rocky Mountains Park, W.S. Ayres, a mining engineer, and R.B. Bennett of the Associated Press at Vancouver. Douglas later negotiated the purchase of the two claims by the Crown and Deutschman surrendered his titles in consideration of a payment of $5,000.12

Cave and Trail Development

When Deutschman agreed to sell his interest in the caves, apparently an understanding was reached with Howard Douglas that he would be employed in the development and operation of the caves.13 Whether or not Deutschman's statement in this respect was correct, Douglas recommended that he be hired as a caretaker, and Deutschman subsequently was engaged on a seasonal basis. Early in 1906, Douglas arranged for the construction of a trail from the railway water tank east of Ross Peak Station to the caves. Deutschman was given authority to construct log cabins for the use of visitors near the station and at the caves. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company opened and maintained a trail from Glacier House to the water tank that linked up with the trail made to the caves. Between 1911 and 1914, the trail from Glacier House to the caves, then used by saddle-horse riders, was developed by the Park Service to the status of a carriage road. In 1915, a tally-ho service was inaugurated from the hotel to the end of the road, which terminated about 1.6 km from the cave entrance. During the period of his employment each year, Deutschman continued his exploration of the caves, built a caretaker's quarters, and installed ladders, hand-rails and other aids for persons visiting the caves. A more accessible entrance to the lower caves was made in 1915 by tunnelling through rock, following a survey by O.S. Finnie, an engineer of the Department of the Interior.

The earliest reports on the unique character and features of the caves were written by W.S. Ayres and Arthur O. Wheeler and appeared in the annual report of the Surveyor General of Canada.14 Ayres had accompanied an inspection party to the caves on May 29, 1905, and, in company of Deutschman, had made further inspections on the last three days of the same month. Wheeler, a staff member of the Topographical Survey of Canada, also made a detailed inspection of the caves in August, 1905. Wheeler's report, accompanied by a plan showing the extent of the caves, contained a very detailed description of the various caverns and passages explored to date. A survey of the lower caves was undertaken in 1927 by another departmental engineer, C.M. Walker of Banff. During the depression years of the "thirties", park appropriations were drastically reduced, and caretaker services at the caves were terminated in 1932. Shortly after, the caves were closed to the public as a safety measure.15 Admission to the caves in later years was authorized by permit, mainly to individuals engaged in scientific observation. Studies carried on by a consultant from 1965 to 1969 increased knowledge of the caves, and disclosed additional passages and caverns previously unknown.

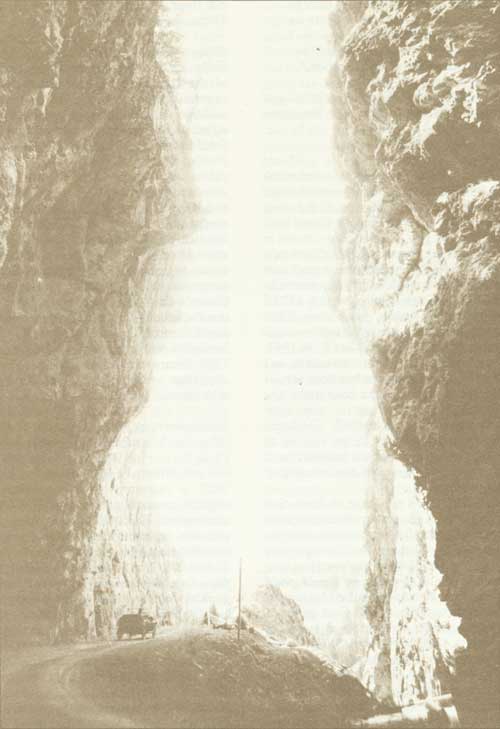

The Connaught Tunnel

The opening of the Connaught Tunnel through Mount Macdonald in December, 1916, by the Canadian Pacific Railway foreshadowed future events in Glacier Park. The heavy grades, the high cost of operating its line over Rogers Pass including the maintenance of kilometres of timber snow sheds, and occasional casualties from slides influenced the Company to commence construction of the tunnel in 1913. The most disastrous slide occurred in March, 1910, when a work crew engaged in extricating a stalled train was engulfed, with a loss of 62 men.

Construction camps were established at each end of the proposed tunnel — 8 km in length — and 1.6 km beneath the summit of Mount Macdonald. The drilling crews met on December 9, 1915, and the Governor General, H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught, officiated at an official opening on July 17, 1916. The new line went into service on December 9 of the same year.16 In addition to eliminating the need for snow sheds through Rogers Pass, the tunnel had the effect of lowering the grade over the summit by 164 m.

With the railway line relocated, the railway settlement and work camp at Rogers Pass Station was closed down and a new station constructed immediately west of the western end of the tunnel. All buildings were moved or demolished, and only the walls of the round house remained. Glacier House, which had been bypassed by the railway relocation, was connected with the new station by a road which utilized part of the abandoned grade. From 1917 on, Glacier House was open during the summer months only, but for several years it operated almost at capacity. In 1923, the C.P.R. built a tea-house with overnight accommodation at the Nakimu Caves, and operated it from 1924 to 1927. An era came to an end, however, when the Railway Company closed Glacier House forever on September 15, 1925.17 The building was allowed to stand for four years. After all furniture and fixtures were removed, it was dismantled under contract late in 1929, and the debris burned. The title to the land occupied by Glacier Station and Glacier House later was surrendered to the Crown.

Visitor Travel Declines

Following the closing and demolition of Glacier House, visitor travel to Glacier Park dwindled. The Swiss guides departed and the saddle horse concession and the tally-hos disappeared. The owner of the store at Rogers Pass Station had moved to a new site near the new Glacier Station. A few visitors were accommodated in the store building but others had to "camp out". Only when mountaineering clubs held an outing in the park was there any concentration of visitors. The Nakimu Caves, however, were open to visitors for several years. C.H. Deutschman accepted more renumerative employment in the United States in 1919, and his successor as caretaker, George Steventon, carried on for several years before the caves were closed. Deutschman died in Connecticut in 1967.

Avalanche Control

The selection of a route over Rogers Pass for the construction of the Trans-Canada Highway from Golden to Revelstoke brought new activity to Glacier National Park. Following surveys by the governments of Canada and British Columbia, clearing of the right-of-way was undertaken by park forces. Construction of the highway under contract was commenced in 1958 and completed, with an initial coat of asphalt, in 1962. Difficulties in maintaining the completed highway were accentuated by a need for the control of avalanches which was met in part by the construction of more than 823 m of concrete snow sheds at critical points. Additional control of avalanches between the eastern boundary of the park and Albert Canyon was developed by the construction of an avalanche observation station on Mount Fidelity. Here highly trained staff equate information obtained and transmitted by automatic equipment from two high-altitude observatories. These observations provide advance warning of avalanche conditions. Dangerous slopes are then stabilized by explosives detonated in the trigger zone of the avalanche by means of howitzers manned by a detachment of the Royal Canadian Artillery. The first observation station was erected on Mount Abbott in 1956 and an additional one at Balu Pass in 1958. The main control station on Mount Fidelity was completed in 1961.

Administration

From the date of its establishment until 1908, supervision of Glacier Park was carried on by the Superintendent of Banff Park. In 1909, a superintendent of Glacier and Yoho Parks, with headquarters at Field, was appointed. Later, when construction of the Trans-Canada Highway through Glacier and Mount Revelstoke Parks was decided on in 1957, a superintendent for the two parks was appointed, with headquarters at Revelstoke. The administrative offices are located in rented premises.

Park Buildings

The first warden cabin in Glacier Park was constructed in 1914 on the Nakimu Caves Road near Glacier Station. In 1916, three seasonal wardens were on duty and wardens' stations were established at Stoney Creek, at Flat Creek and at Glacier Station. In 1921, a bunkhouse, stable, and a new wardens' cabin were erected in the vicinity of Glacier House. In 1936 the Stoney Creek cabin, originally a C.P.R. building, was replaced with a new structure. The Flat Creek Station was rebuilt in 1947. Patrol cabins were built at Grizzly Creek in 1929, Beaver River in 1941, Mountain Creek in 1952 and Bald Mountain in 1953. The construction of the Trans-Canada Highway required relocation of the warden station at Glacier and a new building was built at Rogers Pass Summit in 1961. The Stoney Creek warden station was relocated in 1964 when a new cabin was built in the vicinity of the eastern gateway on the Trans-Canada Highway.

Between 1962 and 1965 an administrative headquarters for the park was developed in Rogers Pass, involving construction of vehicle maintenance and stores buildings and an administration building containing staff quarters and dining facilities. Additional accommodation for staff in the form of apartment blocks was added in 1968. Visitor traffic is controlled at a gateway building inside the eastern park boundary which was erected in 1962.

New Visitor Accommodation

The first visitor accommodation available in the Park since 1925 — Northlander Lodge — was constructed in 1964 by private enterprise. A large motor lodge situated at the summit of Rogers Pass provides modern amenities, including dining services, a heated swimming pool, and a small store and gasoline service station. The needs of campers are met by semi-serviced campgrounds completed in 1963 at Loop Creek and Illecillewaet Creek adjacent to the Trans-Canada Highway. Construction of an additional major campground at Mountain Creek 19 km east of Rogers Pass summit was commenced in 1964. Its completion in 1970 made available 260 tent and 46 trailer sites.

Recreation

Riding, hiking and climbing were or have been the most popular forms of recreation in Glacier Park. Glacier House Hotel formed the headquarters for the alpine fraternity for years and, after its demolition in 1929, mountaineers were obliged to establish tent camps. In 1945 the Alpine Club of Canada acquired a former C.P.R. section house for seasonal use. In 1947, the Club erected the A.O. Wheeler Hut almost opposite the site of the former Glacier House Hotel. The earliest hiking and riding trails in the park were established by the C.P.R. in the vicinity of Glacier House. These included trails to Glacier Crest overlooking Illecillewaet Glacier, to Marion Lake and to a lookout on Mount Abbott. Between 1909 and 1911, the Park Service built a trail from Rogers Pass up Bear Creek to Balu Pass and westerly to join the Nakimu Caves Trail. A fire trail was built from Glacier House to Rogers Pass over the abandoned railway grade between 1911 and 1914 and reconstructed to the status of a fire road between 1940 and 1950. Trails were also constructed from Stoney Creek south up Grizzly Creek to Bald Mountain Summit, and up Flat Creek from the wardens' cabin to the head of the stream. An access road to the Mount Fidelity snow research and avalanche forecasting station was completed in 1961.

Some skiing is carried on in Glacier National Park during the winter months. During the construction of the Trans-Canada Highway, a small rope tow was installed in Rogers Pass on the slopes of Mount Cheops, in the vicinity of the highway construction camp. Later, when Northlander Motor Hotel was opened, the operator extended the ski slope and installed two rope tows. The nature of the hill and the surroundings limit future expansion.

Glacier National Park incorporates many unique features of interest to visitors, including snow-fields, glaciers and deep forested valleys. Its peaks, many of them glaciated, still present a challenge to the ambitious climber, and the Nakimu Caves, when reopened to visitors, will provide a remarkable example of underground caverns formed mainly by water erosion. It has been said "no snows are so white as the Selkirk snows and no clouds so radiant, no forests so darkly, beautifully green". Since the park, after many years, was made easily accessible by a modern highway, its attractions have been enjoyed by a steadily increasing number of visitors.

Endnotes

1. J.M. Gibbon, Steel of Empire.

2. A.O. Wheeler, The Selkirk Mountains (Winnipeg: Stovel Company, 1912), p. 20.

3. Ibid., p. 23.

4. Ibid., p. 27.

5. F.V. Longstaff, "Historical Notes on Glacier House", Canadian Alpine Journal 1948, p. 195.

6. Order in Council P.C. 1886-1880, Oct. 10, 1886.

7. A.O. Wheeler, The Selkirk Range (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1905), p. 374.

8. Order in Council P.C. 1903-1950, Nov. 26, 1903.

9. Order in Council P.C. 1911-1138, Jan. 8, 1911.

10. Order in Council P.C. 1930-134, Feb. 11, 1930.

11. C.H. Deutschman, "Old Grizzly", unpub. manuscript, National Parks Branch File G.324, vol. 2.

12. Order in Council, Dec. 26, 1906.

13. Deutschman. See above, note 11.

14. Report of the Surveyor General, year ended June 30, 1906 (Ottawa: King's Printer, 1906).

15. National Parks Branch File G.2, May 7, 1935.

16. National Parks Branch File G.17 CP1, Dec. 15, 1916.

17. F.V. Longstaff, letter in Vancouver Star, Feb. 9, 1929, National Parks Branch File G.17 C.P.8.

Waterton Lakes National Park

Following the establishment of the Waterton or Kootenay Lakes Forest Park in 1895, it was used as a camping and picnic resort by residents of nearby settlements and communities including Pincher Creek, Cardston, Fort Macleod, and Lethbridge. Visitors to the park apparently were content to occupy the area in its primitive state, for nothing in the form of development or the provision of amenities had been undertaken by the Department of the Interior. Essentially, it was a forest reserve without special supervision or protection. Its timber was available to settlers under permit and prevailing regulations permitted prospecting for petroleum and the reservation of potential oil-producing lands. The early oil rush of 1890-91 had waned, but interest in the petroleum resources of the area had been rekindled in 1898, when the reservation of lands for prospecting of oil and their subsequent sale was authorized by order in council.1 John Lineham, of Okotoks, a former member of the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly, had reserved lands for oil exploration one year earlier along Oil Creek, now known as Cameron Creek, and in 1901 had organized the Rocky Mountain Development Company. Linehain later purchased about 1,600 acres (647.5 ha) of potential oil-producing land at a cost of from $1 to $3 an acre. By November, 1901, Lineham had hauled a drilling rig up the narrow valley of the creek, established a drilling camp, and planned the townsite of "Oil City". Oil was encountered at 311 m in 1902. By the end of 1907, three additional holes had been drilled, but they failed to produce oil in a volume that would make the operation profitable.2

Efforts to locate oil in commercial quantity were carried on by the Western Oil and Coal Company which in 1906 had a hole down to 521 m on a site now situated within Waterton Park Townsite. A flow of one barrel a day had been obtained in October, 1905, but after walls of the well caved in only pockets of oil were found.3

Larger Park Recommended

By 1905 more than half of the sections of land comprising the forest park had been reserved for petroleum exploration, and the associated activities had generated some concern among the conservation-minded residents of the vicinity. On September 21, 1905, F.W. Godsal of Cowley wrote the Secretary of the Interior suggesting that the interest of the public be safeguarded and that consideration be given to an extension of the park reserve. Godsal had sparked the original reservation in 1895, and, as his letter indicated, those using the park were fully aware of its scenic and recreational attractions.

I have lately visited the vicinity again and I may inform you that the beauty and grandeur of the scenery there is unsurpassed, I do not think equalled by anything at Banff. Further, a very large number of people from Pincher Creek, MacLeod, Cardston and other towns resort there every year for camping, it being the only good place now left for the purpose. It is therefore very essential that the interest of the public should be properly safeguarded in this "beauty spot". Firstly, I doubt if the reserve is large enough for its purpose as the land around is very stoney and quite unfit for agriculture or settlement. It can be enlarged without hurting anyone. Further, if parties are allowed to bore for oil there, which personally I regret, but perhaps scenery must give way to money-making, very careful restrictions should be insisted on so that no unnecessary damage or ugliness be done as is insisted on I believe at Banff .... I hope that this letter may reach the eye of the Minister of the Interior himself as I am known to him and he has at heart every interest of the people of Alberta.4

Godsal's letter prompted instructions for an inspection of the area which was carried out by W.T. Margach, Chief Forest Ranger of the Department of the Interior at Calgary. Margach reported on May 4, 1906, to the Secretary of the Interior on the "oil fields of Alberta", including the activities of the Western Oil and Coal Company, the only operator carrying on oil exploration in the reserve at the time. Although it had failed to locate satisfactory oil deposits, the Company had used in its operations over a period of seventeen months more than 2,956 lineal metres of timber for construction purposes and 1,100 cords of wood in generating steam for its drilling rigs.5 More than 50 years later, the residue of the lands within the park which had been granted to John Lineham for oil production were acquired by the National Parks Branch from his heirs at a cost of more than $50,000.

Margach's report also reflected the views of most departmental field officers in respect of resource development. He observed that "owing to the development of the oil wells I think the area of the park quite large enough, as, in my opinion, playgrounds come second with development of the mineral wealth and industries of the country, and can see no area in close proximity to the present reserve that would add value to it as a game preserve or has any features that the present area has not".

Margach, however, did recommend that development should not be permitted to extend to the shore of Upper Waterton Lake and that surface rights should be confined to areas essential to the particular development concerned. A summary of Margach's report was referred by the Superintendent of Forestry to the Deputy Minister of the Interior with the recommendation that no action be taken pending the introduction in Parliament of a bill to establish forest reserves which would incorporate Kootenay Lakes or Waterton Forest Park.

Kootenay Lakes Forest Reserve

The Dominion Forest Reserves Act came into force on July 13, 1906.6 It established the forest park around Waterton Lakes as the Kootenay Lakes Forest Reserve and placed it, along with other reserves, under control and management of the Superintendent of Forestry at Ottawa. On May 27, 1907, Inspector Margach was asked by the Superintendent of Forestry for a report on the area "as it is the intention to make a provision for the proper administration of the reserve in question".7 Departmental records do not contain a copy of the requested report, but action toward setting up a local administration was taken by the Department of the Interior in April 1, 1908, when Rocky Mountains Park and other park reserves were placed under the administration of the Superintendent of Forestry at Ottawa. A move for the establishment of the Kootenay Lakes Forest Reserve as a National Park was supported by John Herron, M.P., and John George (Kootenai) Brown who, since 1892, had occupied the only freehold in the reserve. After consultation with Brown, Herron recommended to the Superintendent of Forestry that Brown be placed in charge of the park. A recommendation by the Superintendent of Forestry to the Deputy Minister was later approved and Brown was appointed Forest Ranger in charge of the park on April 1, 1910.8 Although Brown was then 70 years of age, his qualifications for the position were exceptional, as he had served as Fishery Officer for the Department of Marine and Fisheries in the district since January 1, 1901. This post he retained until March 31, 1912, and he continued as acting park superintendent until September 1, 1914.

Waterton Lakes Park Created

The future of the Kootenay Lakes or Waterton Reserve was affected profoundly by developments in 1911. The first was the enactment of the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act9 which provided for the administration of both Forest Reserves and Dominion (National) Parks, and for the establishment as Dominion Parks of lands situated within forest reserves. The second development was the creation of a new branch of the Department of the Interior, the Dominion Parks Service, to administer under the direction of a commissioner both existing and new parks. Subsequently, out of an enlarged Rocky Mountain Forest Reserve, was established on June 8, 1911, Waterton Lakes Dominion Park with a reduced area of 35 km2.10 This reduction, which left the park with little more than the slopes of the mountains bordering the west sides of Upper and Middle Waterton Lakes, must have been a severe disappointment not only to the new park ranger but to those who had been recommending enlargement of the park. It seems clear that the new Commissioner of Parks at Ottawa, J.B. Harkin, had no part in the reduction of the areas of not only Waterton Lakes, but also Rocky Mountains and Jasper Parks. In fact, the new act elevated the status of the newly enlarged forest reserves at the expense of the older parks and park reserves. A partial explanation of the reasoning behind the action was provided by the Superintendent of Forestry, R.H. Campbell, in a letter addressed to F.K. Vreeland of New York City, an active member of the Campfire Club of America. This group had been advocating the enlargement of Waterton Lakes National Park as a natural continuation of the recently established Glacier National Park in Montana, with a view to protecting the native wildlife which was in danger of extinction. Mr. Vreeland had expressed his disappointment over the withdrawal of lands from Waterton Lakes Park when an enlargement had been expected. As Mr. Campbell explained the situation:

The policy of the former Minister (The government had been defeated in the September, 1911, election) of the Department in regard to Forest Reserves in Parks is apparently not very well understood. The position he took in regard to the matter was that forest reserves should be formed for the protection of the forest and also the fish and game where it was considered necessary. By the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act which was passed by Parliament during the past summer, the whole eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains in Canada was made a Forest Reserve and that Act, a copy of which I enclose herewith, gives authority to make any necessary regulations for the protection not only of the forest but the fish and game also. ... His idea of parks was very different from the idea as accepted by many others. He considered a park as a place where people could be induced to come as much as possible to be given as much freedom to travel as could possibly be given. For this purpose he considered that the parks need not to be of large area but might be smaller even than those which had been previously established. You will see therefore that the reduction in the area of the park was not carried out with the intention of reducing the area in which the game would be protected but merely of reducing the area to which free access would be given and to which people would be invited, and that the protection of the game was to be provided under forest reserve regulations.11

Park Area Enlarged

Fortunately the area of Waterton Lakes Park was to be readjusted in less than three years. Recommendations by the new commissioner, J.B. Harkin, supported by public opinion, led to the extension in June, 1914, of the park boundaries to include an area of 1,096 km2.12 The enlarged park encompassed the colourful main range of the Rockies east of the continental divide, from the International Boundary north to North Kootenay Pass and the Carbondale River. The expanded park also included the portion of Upper Waterton Lake in Canada, together with the middle and lower lakes and a portion of the Belly River Valley. Inter-departmental rivalry for the control of game populations in the enlarged park led to enactment of an order in council which placed the park area containing the watersheds of Castle River and Scarpe Creek under the control of the Director of Forestry, exclusive of the game population, which continued to be the responsibility of the Commissioner of National Parks.13 This arrangement, however, proved to be unsatisfactory both to the Forestry Branch and the National Parks Service and, in 1921, the northwesterly portion of the park which had been under dual administration was withdrawn and later reincorporated in the Rocky Mountains Forest Reserve.14 The resulting park area of 570 km2 remained intact until 1947 when 41 km2 of burned-over timber land at the southeastern corner of the park were withdrawn. This action followed negotiations with the Province of Alberta about national park land requirements, which resulted in the acquisition of additional territory for the enlargement of Elk Island National Park. The latest reduction in the area of Waterton Lakes Park was made in 1955, when 305 ha in the vicinity of Belly River were withdrawn to facilitate access by the Blood Indian Band to its timber limit which was located in the southeastern portion of the park.

Townsite Surveyed