Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

The Old Fort Point Site: Fort Wedderburn II?

by Karlis Karklins

Introduction

Historical Background

Although the Canadian fur trade had been expanding westward from its

inception, the period of major English expansion northwest of the Great

Lakes began in the 1770s (Smythe 1968: 10, 17). During this period, the

Montreal pedlars began turning their attention to the country that lay

to the north of the Saskatchewan River. The Frobisher brothers were the

first to enter the area and had penetrated as far as

Ile-à-la-Crosse by 1776 (Smythe 1968: 16). Their profitable

ventures proved that the area was rich in furs, and as a result other

traders followed shortly thereafter.

One of the first to exploit the new territory was Peter Pond who, in

1778, established Pond's Fort on the Athabasca River, about 30 to 40

miles from its mouth. Operating as a "free trader" for the first few

years, Pond became a partner in the newly formed North West Company in

1785 which thereby gained the only post in Athabasca (Chalmers 1974:

51). Pond's Fort functioned for another three years and was then

abandoned for a site on Lake Athabasca since the old establishment was

not in a suitable location either as a base for the exploration of the

country to the north and west of the lake or to adequately trade with

the Indians of the region. Further, it lacked the resources to support

an establishment large enough to meet the future requirements of the

Athabasca area (Smythe 1968: 249).

The new post, Fort Chipewyan I, was constructed in 1788 by Roderick

Mackenzie on a small peninsula on the south shore of Lake Athabasca,

about 6 miles to the east of the Athabasca River delta. This location

was in the centre of excellent fisheries and near the mouths of the

Athabasca, Slave and Peace rivers and at the hub of a vast network of

water routes. It was also about as far west as a post could be placed

and still allow canoes from the fort to rendezvous at Grand Portage in

the summer, exchange furs for supplies and return to the north before

the rivers and lakes froze over (Chalmers 1971: 8).

Although relatively little is known about this post, it was a

sizeable operation, being deemed "the compleatest Inland House I have

seen in the Country" and "the Grand Magazine of the Athapiscow Country"

by Philip Turnor who visited the site in 1791-92 (Tyrrell 1934: 398).

During the 12 years of its existence, Fort Chipewyan I served as company

headquarters and as the chief trading establishment in Athabasca, as

well as a base of operations for the exploration of the northwest and

the subsequent expansion of the North West Company into the explored

regions. The fort was also a redistribution centre for furs coming from

and supplies going to the other posts in the district.

In the late 1790s, the importance of Fort Chipewyan I began to

decline. The tremendous expansion of the Athabasca Department during

this period was at the root of the difficulty (Smythe 1968: 250). With

posts westward along the Peace River and north on the Mackenzie

diverting some of the concern's attention, Fort Chipewyan suffered.

Consequently around 1800, the post was relocated on the lake's northwest

shore in the immediate vicinity of the present settlement of Fort

Chipewyan, Alberta. This locale was free of ice sooner than the old

site, thereby allowing the earlier departure of the traders in the

spring. It was also much closer to the Slave and Peace rivers, as well

as nearer to the major fur suppliers, the Chipewyans, whose territory

lay to the east and north of the lake.

The move did not end the post's troubles however. At about the same

time that Fort Chipewyan was relocated, Alexander Mackenzie's XY Company

established a post in the immediate vicinity (Smythe and Chism 1969:

89). Further competition in the form of the Hudson's Bay Company

appeared in 1802, when Peter Fidler established Nottingham House on

English Island about two miles from Fort Chipewyan II. Nevertheless, the

competition was short-lived. By 1806, the North West Company had

absorbed Mackenzie's concern and driven the Hudson's Bay Company from

the area (Smythe 1968: 246, 248). With the two companies out of the way,

the Nor'Westers once again had a monopoly in the Athabasca region.

It was not until 1815 that the Hudson's Bay Company reentered

Athabasca to challenge the North West Company's hold on the area once

again. In that year John Clarke, a former Nor'Wester, built Fort

Wedderburn on Potato Island opposite Fort Chipewyan. This post was

occupied until October of 1817, when it was decided that a residence on

the island would not be feasible that winter because of a lack of dogs

to haul fish to the fort from the outlying fisheries (Krause 1972: 28).

Temporary headquarters (Fort Wedderburn II) were, therefore, erected on

Old Fort Point which had always been considered an excellent fishery.

However, the new location did not prove to be any better than the old

one had been; by 25 March 1818, the Hudson's Bay Company men were back

on Potato Island (Krause 1972: 29).

Fort Wedderburn continued in existence until 1821, when the union of

the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company brought an end to

the bitter rivalry between the two establishments. Fort Wedderburn was

subsequently abandoned and Fort Chipewyan II became the Hudson's Bay

Company's district headquarters and principal northern depot for western

Canada.

Although the importance of Fort Chipewyan II declined gradually after

1821 due to the depletion of the fur resources of the area, it remained

the main trading post in the Athabasca District for over a century

(Smythe 1968: 247); however, as the fur trade in the district

diminished, the need for the post diminished as well. Hence, in 1939-40,

the buildings at the site were either torn down or moved to new

locations to serve as storage facilities and a modern Hudson's Bay

Company store was erected in the town that had grown up around the post

over the years. Now only a stone cairn marks the site of the post that

was once called the "Emporium of the North."

Geographical Setting

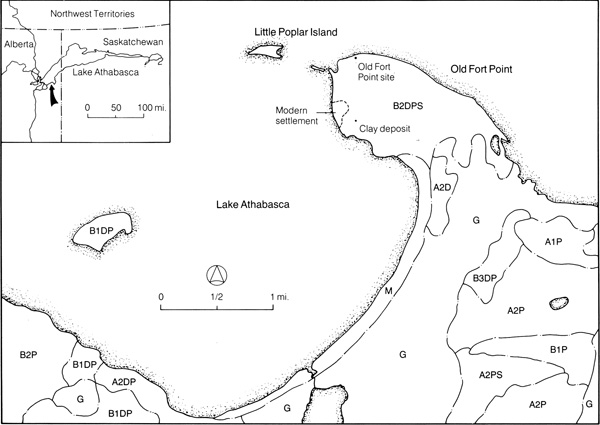

The site discussed in this report is located on Old Fort Point, a

small peninsula at the west end of Lake Athabasca in the extreme

northeast corner of Alberta (Fig. 1). The point is approximately 21

miles to the east-southeast of Fort Chipewyan, the nearest community, at

latitude 58° 39' N. and longitude 110° 36' W.

1 Map of the Old Fort Point area showing site location and vegetation

zones. Forest density: A, sparsely stocked; B, medium

stocked. Tree height: 1, up to 31 ft.; 2, 31 to 60 ft.;

3, 61 to 80 ft. Vegetation type: D, deciduous trees;

G, treed grassland; M, graass marsh; P, pine;

S, white spruce.

(Drawing by S. Epps.)

(Click on image for a PDF version.)

|

The peninsula, approximately 0.75 miles wide and 1.75 miles long,

juts northwest from the south shore of the lake approximately 6 miles to

the east of the Athabasca River delta. A small, sheltered bay is located

west of the point and Old Fort Bay, which is larger, is to the east.

The land at the extreme northwest tip of the peninsula is very low

and moist; dry land is just slightly above the level of the beach at an

elevation of 701.97 ft. ASL (Canadian Engineering Services, Ltd., Bench

Mark 36). From here, the land rises gradually toward the mainland,

achieving an altitude of over 900 ft. ASL in a prominence about 0.75

miles east of the bench mark. The land is below 800 ft. ASL elsewhere on

the peninsula.

The Old Fort Point site is approximately 600 ft. east of BM 36, at an

estimated elevation of 718 ft. ASL. It is on the crest of a gradual

slope up from the west and 25 ft. to the south of the edge of a

15-ft-high steep bluff that forms a portion of the north side of the

point (Fig. 2). The land continues to increase in elevation east of the

site, while it slopes down toward a marsh to the southeast.

Although the bluff is stable adjacent to the site — being

overgrown with moss and trees — several old, narrow, slumped

terraces indicate that erosion has taken place at some time in the past.

The extent of erosional activity and its effect on the site, if any, are

not known. A wide cobblestone beach extends to within 7 ft. of the

bluff's base.

Old Fort Point is situated in the southern fringe of the permafrost

region at the transition between the Upper Mackenzie and the Athabasca

South sections of the Boreal Forest Region of Canada (Rowe 1972: 44-5,

154). In the Upper Mackenzie Section, west of Old Fort Bay, white spruce

(Picea glauca [Moench] Voss) and balsam poplar (Populus

balsamifera L.) constitute the main forest cover on the alluvial

flats bordering the rivers. Few other species occur although balsam fir

(Abies balsamea [L.] Mill.) and white and Alaska birch (Betula

papyrifera Marsh. and B. neoalaskana Sarg.) are prominent

south of Lake Athabasca. On the benches above the flood plains an

entirely different forest pattern exists. Here jack and lodgepole pine

(Pinus banksiana Lamb. and P. contorta Dougl.), trembling

aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.), black spruce (Picea

mariana [Mill.] B.S.P.) and tamarack (Larix laricina [Du Roi]

K. Koch) predominate, while white spruce occurs only in minor quantities

(Rowe 1972: 45). The soil cover in the section typically consists of

deep deposits of glacial tills or more recently deposited lacustrine and

alluvial materials overlying Devonian and Cretaceous bedrock. Gray

luvisols and eutric brunisols are developed on well-drained sites in the

Athabasca area, although immature profiles are more usual in alluvium

(Rowe 1972: 45).

The Athabasca South Section east of Old Fort Bay is characterized by

jack pine, black spruce and tamarack. White spruce, trembling aspen and

balsam poplar are uncommon except along river valleys and lake shores

where there is good growth. The sandy soils are derived from the

underlying sandstones (probably late Precambrian) by glacial action.

Humo-ferric podzols, gleysols and organic (peat) soils are present (Rowe

1972: 44).

On Old Fort Point itself, the forest cover is of medium density and

consists of white spruce, jack pine, trembling aspen, balsam poplar,

white birch and alder (Alnus sp.). Shrubs are represented by the

common juniper (Juniperus communis L.), saskatoonberry

(Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.) and choke cherry (Prunus

virginiana L.). Wild raspberries (Rubus sp.) and strawberries

(Fragaria sp.) occur in scattered patches, and there are several

species of flowers, including wild roses (Rosa sp.). Grass and

moss grow in areas not choked with the omnipresent juniper bush. Willows

(Salix sp.) and horse tails (Equisetum sp.) are common

along the beach.

In the vicinity of the site, the dominant growth on lower ground (to

the west of the site) is trembling aspen, white birch and juniper. To

the east, on higher ground, the dominant types are white spruce and

birch with scattered jack pine. The site is located at an elevation

where white spruce and jack pine first appear, and was probably chosen

for a building location so it would be adjacent to a source of good

timber.

The soils are, for the most part, podzols consisting of Pleistocene

and post-glacial sediments and are characterized by a distinct, leached,

strongly acidic whitish or grayish Ae horizon underlain by a reddish Bf

horizon in which accumulate oxides of iron and aluminum (Lindsay et al.

1962: 30, 33; Rowe 1972:164). The soil cover rests on Precambrian

Athabasca Sandstone which forms a part of the Precambrian Shield

(Lindsay et al. 1962: 33).

The climate in the Athabasca Region is classified as dry subhumid

(Rowe 1972:155). The average annual rainfall is 7.6 inches while the

average annual snowfall is 44 inches. Average rainfall and snowfall are

highest in July (1.8 inches) and November (9.1 inches) respectively

(Canada. Department of Transport. Meteorological Division 1954:

20-21).

The annual mean temperature in the area is -6.7°C. January is the

coldest month with an average daily mean temperature of -23.9°C. The

warmest month is July with an average daily mean temperature of

17.2°C. From November to April, the average daily mean temperature

is below 0°C (Canada. Department of Transport. Meteorological

Division 1954: 15).

The prevailing wind in the vicinity of Old Fort Point is from the

north and is frequently quite strong since there is nothing to break its

force as it sweeps across the lake. Subsequently, the lake is usually

choppy along the south shore and often unnavigable by small boats,

swells over five feet in height not being uncommon. The area is also

subject to sudden storms which can come up in a matter of minutes. On

one occasion during the 1971 field season, the author witnessed the

approach of a storm front from the northwest wherein the wind speed

changed from perfect calm to an estimated 40 to 50 miles per hour in

less than 15 minutes. Similar occurrences were also recounted by several

local residents.

Archaeological Techniques

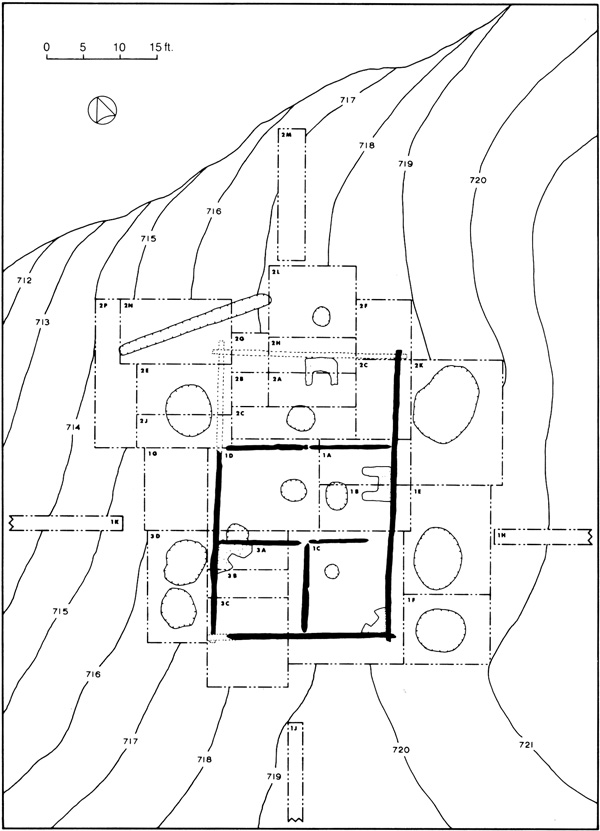

When the archaeological field party arrived, the Old Fort Point site

was marked by eight depressions and three probable fireplace mounds

which occupied an area approximately 45 ft. square. The area was

overgrown with a dense stand of vegetation and had not been previously

disturbed.

After the site had been cleared, three test trenches were dug in what

appeared to be strategic areas to recover a sample of artifacts which

might shed light on the date and identity of the site as well as to

obtain information concerning the orientation and size of the structure

or structures involved. When this had been accomplished, the site was

divided into horizontal units (Fig. 2) which would facilitate the

recording of uncovered features and the assignment of artifacts to

specific sections of the site for interpretative purposes.

2 Contour map of the Old Fort Point site showing the excavation units.

The solid black areas represent the remnants of building walls while the

dashed lines indicate where walls once existed. The stippled areas

denote fireplaces.

(Drawing by E. Lee.)

(Click on image for a PDF version.)

|

Each horizontal unit was subsequently excavated stratigraphically in

order to segregate recovered artifacts and structural components to

determine if the site had been occupied more than once. Due to the

shallowness of the overburden, the digging was performed using hand

tools such as trowels, grapefruit knives and brushes from the start so

that the recovery of cultural objects, faunal remains and structural

features would be as complete as possible. To further facilitate the

achievement of this objective, all flooring was removed after being

recorded and the areas beneath were excavated to sterile subsoil. In

addition, when small objects like beads and lead shot were encountered,

the soil in their immediate vicinity was screened through both 1/16-inch

and 1/4-inch hardware cloth to ensure the recovery of as many small

items as possible. Screening of the fill at other times was not

performed since the paucity of small objects during several trial

periods when all soil was screened indicated that constant screening was

not warranted.

During excavation, all features and stratigraphic layers were

recorded as they were uncovered so no information would be lost. To

facilitate the comparison of the features at the Old Fort Point site

with those described in historical documents and other site reports, all

measurements were recorded in feet and tenths of feet.

After the core area of the site (a single, large building) had been

excavated, a trench was dug perpendicular to each side of the area in an

effort to locate other features (Fig. 2). No evidence of any additional

structures or occupation areas was uncovered in any of the trenches. The

completion of these trenches marked the end of the project and the site

was backfilled to return the area to as natural a state as possible.

Stratigraphy

Five major stratigraphic layers and numerous localized zones were

encountered at the Old Fort Point site. The major layers were present in

all or most of the excavation units; the localized zones were spatially

restricted.

Layer 1

Moss and decaying vegetal material (primarily juniper needles)

comprised the uppermost layer which was 0.01 ft. to 0.5 ft. thick (0.14

ft. average). This detritus was deposited after the site fell into ruin

and was overgrown with vegetation.

Layer 2

Directly below layer 1 was a stratum of yellowish red and white sand

which contained scattered charcoal, artifacts and lenses of both dark

brown sandy clay and reddish brown sandy clay. This material was up to

1.65 ft. thick, averaging 0.48 ft., and originally covered the roof of

the solitary building at the site.

Layer 3

Under the sand was a discontinuous layer of dark brown sandy clay

which contained small lenses of sand, charcoal flecks, fish remains,

wood chips and birch bark. This stratum was up to 0.35 ft. thick, with

an average of 0.22 ft., and constituted the material used to chink the

roof of the building. This and the previous layer tapered out at a

distance which varied from 4.5 ft. to 9.5 ft. to the north, east and

south of the structure. To the west, where the ground sloped noticeably

and erosion had washed the material downhill, the sand and clay

terminated 18 ft. from the building.

Layer 4

The fourth layer was a charcoal deposit up to 0.3 ft. thick (0.07 ft.

average) which covered the sterile subsoil in the immediate vicinity of

the building, and apparently represents overgrowth burned off prior to

the construction of the structure. The charcoal tapered to a distance of

15 ft. to 25 ft. from the building on all sides, suggesting that an area

only slightly larger than the structure was thoroughly cleared.

Layer 5

Layer 5 was the undisturbed soil underlying the site, consisting of

well-drained, white sand overlying yellowish red sand which rests on

fine to coarse gravel. No clay was encountered, indicating that the clay

used to chink the building was obtained elsewhere on the peninsula.

The localized zones consist of pit fill and fireplace ash, and

are described in the 'Description of Features' portion of this

report.

|