|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 25

Gothic Revival in Canadian Architecture

by Mathilde Brosseau

Illustrations and Legends

63

Hydraulic Power Station, Blair, Ont.

Material: wood

This tiny power station is a further indication of the enthusiasm for

Gothic Revival even in industrial architecture. Its board-and batten

siding shows a desire to identify with the Neo-Gothic style, in the same

way as the treatment of the small pointed windows. In this particular

case, the thoroughly romantic surroundings may have affected the choice

of the Gothic Revival style.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

64

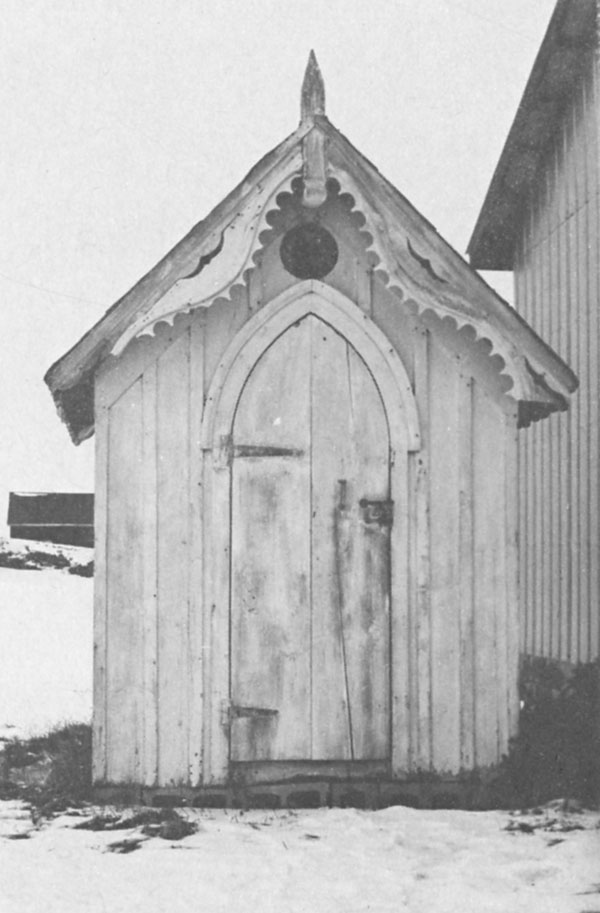

Outhouse, 112 Main Street, Waterford, Ont.

Material: wood

In the same way as some birdhouses, this small outhouse mimics the style

of the nearby family dwelling. It seems to confirm the fact that, once

the Gothic Revival was established as a popular fashion, few

architectural sectors could resist its influence!

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

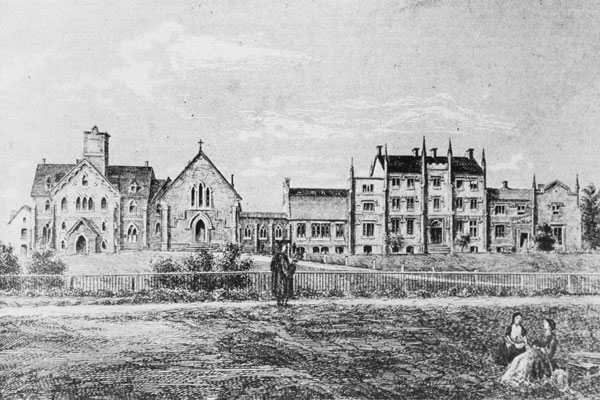

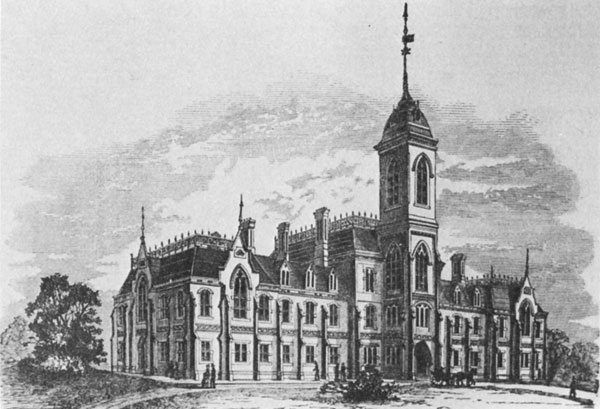

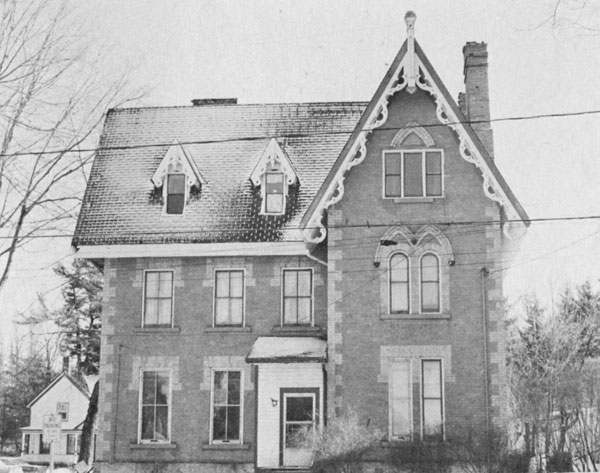

65

Trinity College, Queen Street, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: 1851 (demolished: 1956)

Architect: Kivas Tully

Material: brick

Trinity College was one of the first great Gothic Revival architectural

complexes in the Canadian institutional sector. Its architect, Kivas

Tully, was to spread the style in the sector throughout Ontario. The

prestigious design of the college draws its inspiration from the plan

and, to some extent, the formal repertoire of the great British colleges

of the Middle Ages.

In 1916, it was decided to build a second Trinity College, this time on

the University of Toronto campus. Impressed by the prestige of the

former Trinity College, the architects for the new project designed an

imitation of the old one. The first Trinity College survived until 1956,

when the city decided to demolish it.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "Trinity College,

Toronto," Vol. 3, No. 24 [June 24, 1871], p. 388.)

|

66

Bishop's University, Lennoxville, Que.

Constructed: 1846 (later additions)

Material: brick

Bishop's College was incorporated by a law passed by the provincial

legislature in 1843 and it was given the status of a university in

1853. Its beginnings were quite modest. The initial project of 1846 was

limited to a three-storey building seen at the right of the engraving.

To it were added an auditorium, a primary school, a chapel and a

residence for professors, so that the complex already reached the stage

shown in the engraving by 1865. Later, there were several fires in the

college. The various reconstructions did not succeed in preserving the

original character of the complex.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "University of Bishop's College,

Lennoxville," Vol. 6, No. 10 [April 27, 1872], p. 258.)

|

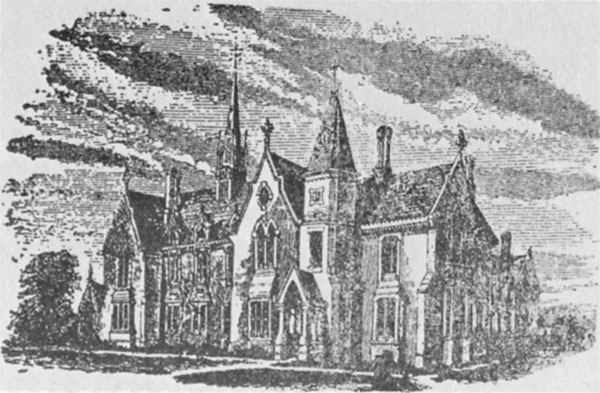

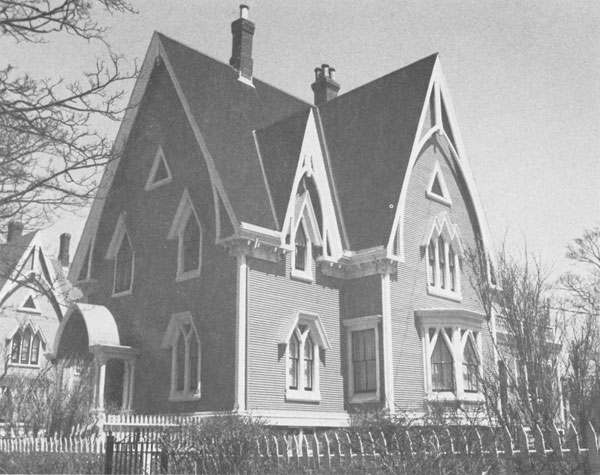

67, 68 Angela College or Mount St. Angela, 923

Burdett Street, Victoria, B.C.

Constructed 1865

Architect: John Wright

Material: brick

In a town like Victoria, which had cherished its British mores and

tastes since it was founded the construction of a Gothic Revival

college, even as early as 1865, is not particularly surprising. The

funds required to build the college were generously provided by Lady

Angela Burdett Coutts, an extremely wealthy English lady who had also

provided the young colony with an Anglican Bishop by supplying the funds

for his salary. Architect John Wright's initial project was an ambitious

one clearly influenced by the type of Gothic Revival College that was

being built at that time in England. But only the main body was built.

(F.A. Peake, The Anglican Church in British Columbia [Vancouver,

Mitchell Press, 1959], p. 75; Canadian Inventory of Historic

Building.)

|

69

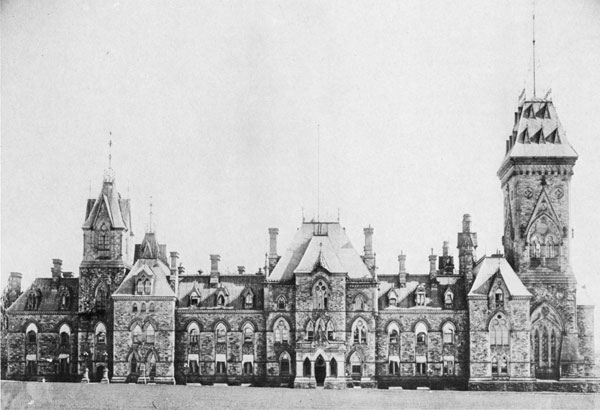

Government House, Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ont.

Constructed: 1859-66

Architects: Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones

Material: stone

These are the prestigious Parliament Buildings as they were seen by

passersby on Wellington Street when they were completed in 1866. The

composition shows the architect's desire to highlight two aspects: the

dignity inherent in the building's function and the imaginative,

vigorous aspect of the Gothic Revival as interpreted at that time. To

heighten the eminence of the parliamentary institution, the architects

used a traditional articulation: a long rectangular building governed by

a plan of corresponding axes, symmetrically articulated and punctuated

at regular intervals by mansard-roofed pavilions. But it was the

treatment of proportions and materials, as well as the choice of

ornamental motifs that gave this elevation the spirit of High

Victorian Gothic.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

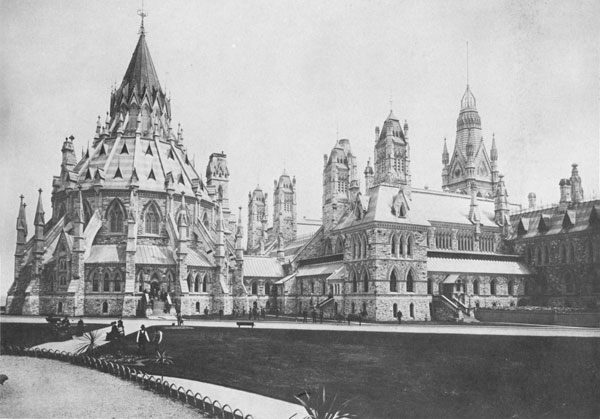

70

Government House (rear elevation), Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ont.

Constructed: 1859-66

Architects: Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones

Material: stone

In the rear elevation of the Parliament Buildings, the architects seem

to have devoted themselves to unbridled exploitation of the picturesque

visual possibilities of the site along the steep bluffs running down to

the Ottawa River. This photo is a good illustration of the vivacity

contained in the Fuller and Jones composition through its irregular

design, spontaneous projections and numerous towers meant much more to

please the eye than meet functional needs. This elevation is dominated

by the stout silhouette imitating a medieval chapter house adapted for

the occasion to the function of library. Since its appearance in the

Oxford Museum in 1855, this design has been included in many Gothic

Revival compositions. Only this library survived the devastating fire

that destroyed the Parliament Buildings in 1916.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

71

Right wing of the parliamentary complex, Wellington Street, Ottawa,

Ont.

Constructed: 1859-66

Architects: Thomas Stent and Augustus Layer

Material: stone

This right wing of the ministerial building reflects the 1859

central building in both the overall spirit and the use of identical materials.

The privacy of a residential building is in keeping with its function as

ministerial offices and the architects chose to amplify the theme of

picturesqueness and irregularity. Instead of the solemn plan designed by

the Fuller and Jones firm for the Parliament Building, the architects

for this building used a more flexible L-shaped form along which the

civil service offices are arranged in an ordered series. In the

exterior treatment, the mansard-roofed pavilion articulation is

reproduced, but the solemn aspect is countered by the intrusion of

unexpected projections and towers with humourous silhouettes.

This is the only building in the parliamentary complex that has remained

almost intact to the present day. Only an additional wing built in

1910-11 to house the Department of Finance has altered the original

articulation by turning the L-shaped plan into a quadrangle.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

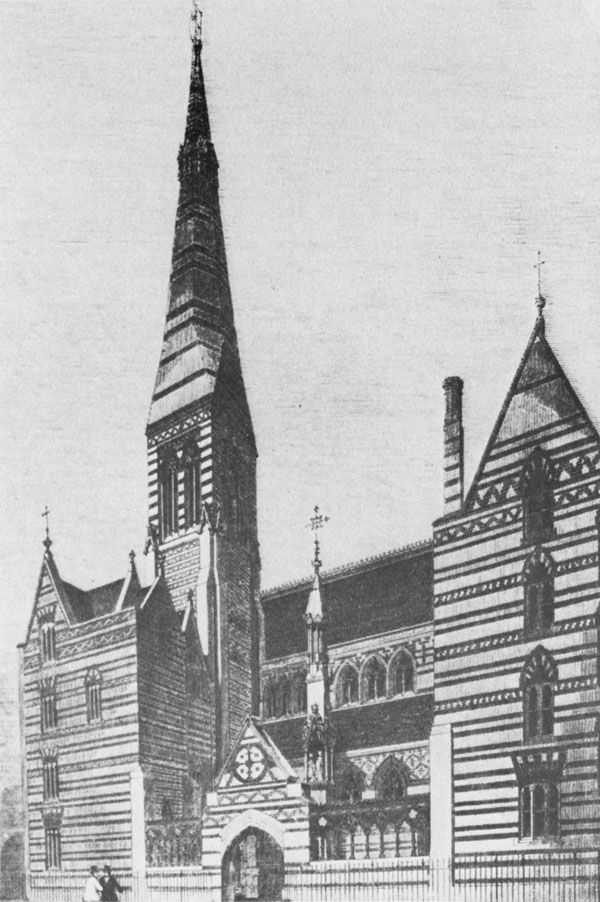

72

All Saints Church, Margaret Street, Saint Marylebone, London,

England

Constructed: 1849-53

Architect: William Butterfield

Material: brick

In this building, the architect revived the use of brick, which had long

been decried in London, and goes so far as to include strip of black

brick in its red walls, thus adhering to the principle of construction

polychromy propounded by the aesthete John Ruskin. But the originality

of this composition goes further: stimulated to a great extent by the

cramped site, Butterfield gave a vertical expansiveness to each element

of the composition and gave preference to interpenetrating forms. These

were features of a new freedom of expression that was to influence the

design of many Gothic Revival churches during the last decades of the

19th century, both in Europe and in North America.

(The Builder [London], No. 57 [Jan. 1853].))

|

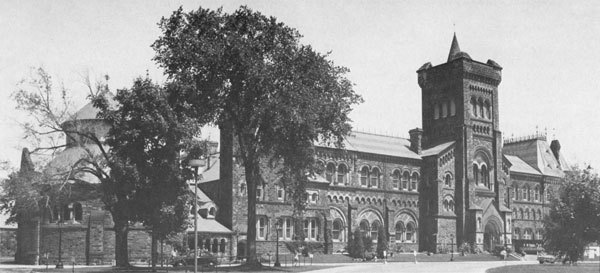

73

University College, University of Toronto campus, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: 1856-59

Architects: Frederick Cumberland and William Storm

Material: stone

University College stands out as an illustration of the great talent of

Cumberland and Storm, who managed to meet all the functional

requirements of a university-college while creating a composition in

which beats the heart of an architectural era. On February 14, 1890, the

building was heavily damaged by a fire. Its prestige dictated a faithful

restoration of the original composition, which was carried out by

Toronto architect David Dick.

(Photo: G. Kapelos.)

|

74

Oxford University Museum, Oxford, England

Constructed: 1855 (demolished)

Architects: Deane and Woodward

Material: stone and marble

This building was an object of fascination in European and American

architectural circles. It is the only building directly influenced by

Ruskin in the choice and treatment of its decorative repertoire. The

building consists of a rectangular block interrupted by a central

tower. The laboratory attached to the central building imitates the

chapter houses of the English Middle Ages. However, the innovation of

this composition is found more in the details than the articulation. The

windows on the ground floor imitate those of medieval Venetian palaces;

they are paired and divided by a marble mullion and decorated by

delicate tracery surrounded by sculpted motifs. In other parts of the

outer wall, pieces of marble in varied tones enhance the chromatic

effect of the roof covered with green and mauve shingles.

(George L. Hersey, High Victorian Gothic: A

Study in Associationism [Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press,

1972], p. 194.)

|

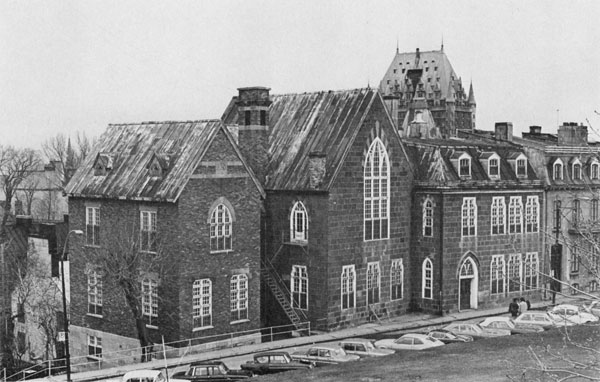

75

Quebec High School, 30, Saint-Denis Street, Quebec, Que.

Constructed: 1865

Architect: Edward Staveley

Material: stone

Without straying far from the architectural conservatism of Quebec,

this composition by Staveley does include some innovations. Student

facilities are divided into two different structural bodies: the first,

housing the main classrooms and dormitories, has a mansard roof which

would never have been associated with the Gothic Revival in the 1830s

or 1840s. A more picturesque quality is produced by the juxtaposition

of a wing with a very steep roof that serves as a chapel. There is even

a timid attempt at construction polychromy in the inclusion of voussoirs

of contrasting colours on some of the bays in the composition. The brick

wing at the left was added toward the end of the 19th century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

76

Ontario Institute for the Blind, Brantford, Ont.

Constructed: 1871 (demolished)

Architect: Kivas Tully

Material: brick

In its article featuring the opening of the Ontario Institute for the

Blind, the Canadian Illustrated News described the style of the

building in the following terms: "The building is designed in the 'Tudor

style' adapted to modern requirements, a style which now prevails in

England, the only innovation being the application of the 'Mansard

roof,' by which more convenient rooms will be available in the third

storeys, and afford additional height on the centre building and the

wings." This description highlights the eclecticism of the composition,

which is attributed by the author to the need to adapt the building to

modern living requirements, for which the mansard roof was used. In this

context, the reference to the Tudor style would appear to be more of an

attempt to dignify a building that includes details, such as false

buttresses, stepped gables and large pointed windows with drip

mouldings, that were very freely interpreted in terms of the different

periods of the Gothic era.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "Ontario Institute for the

Blind, Brantford, Ontario," Vol. 2, No. 11 [March 18, 1871], p.

172.)

|

77

Knox College, 1 Spadina Crescent, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: 1873

Architects: Smith and Gemmell

Material: brick

The proud silhouette of Knox College stands at the head of the large

Spadina artery, from which it is separated by a lawn interrupted by

crescent-shaped driveways. The articulation of the building no longer

has the informal aspect of the Gothic Revival institutions built in the

middle of the 19th century. The symmetrically arranged masses around

the main body of the building show the formal discipline revived by the

Second Empire style. However, unlike many contemporary colleges and

institutions, Knox College does not adopt the mansard roof, which was

also a Second Empire feature. It gives preference to the vertical accent

of the gable roof, which is well in keeping with the linear treatment

of the decorative gables and fenestration.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

78

St. John's College, Winnipeg, Man.

Constructed: ca. 1883 (right wing only) (demolished)

Architects: Charles Arnold Barber and Earl W. Barber

Material: brick

The project for the construction of a new complex for St. John's

Anglican College was to rank among the great architectural creations of

this period. Encouraged by the general atmosphere of prosperity, the

Barber brothers designed a project of remarkable scope marked by the

formal vitality that was so characteristic of High Victorian Gothic.

Mansard-roofed towers with highly fanciful profiles alternated with

pavilion-like structures decorated with ornamental gables gave the

composition a mobile silhouette that was considerably enhanced by the

treatment of the walls. In 1883, the building boom declined considerably

and the St. John's College project, like so many others, had to be

drastically cut back; only the right wing of the structure could be

built.

(Manitoba Archives.)

|

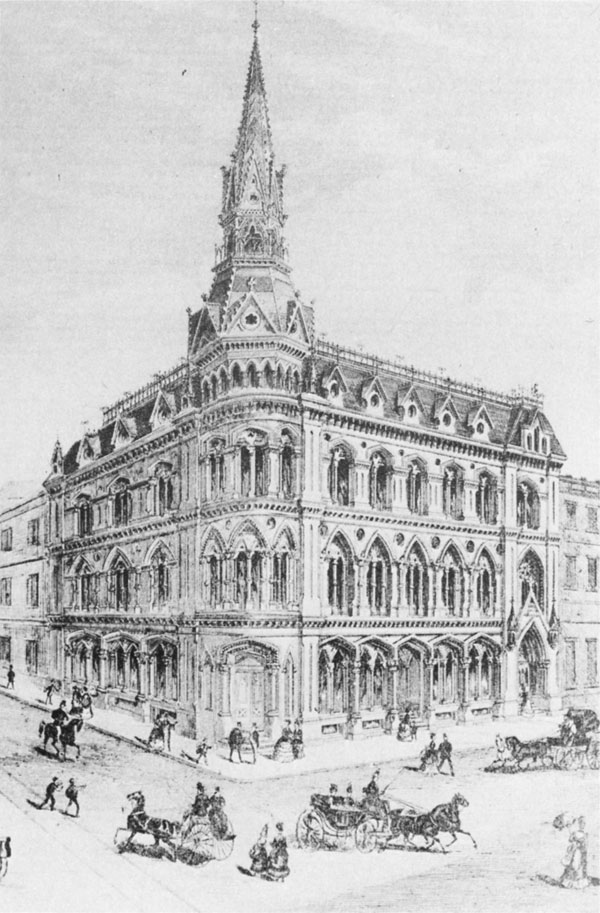

79

Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) building, Victoria Square,

Montreal, Que.

Constructed: 1872 (demolished)

Material: stone

In the 1870s, prestigious YMCA headquarters were established in various

cities across the country. Many of these preserve the Gothic Revival

stylistic mantle that the public easily identified with the educational

sector. The Montreal YMCA was designed to present a stately fašade on

Victoria Square and preserved the typical articulation of Second Empire

public buildings in the form of tiered orders, its corbelled cornice and

mansard roof. On the other hand, almost the entire decorative repertoire

belongs to the "Ruskin style" Gothic Revival which is well illustrated

by the refined fenestration.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "The New Building

of the Montreal Young Men's Christian Association, Montreal," Vol. 6,

No. 10 [September 14, 1872], p. 163.)

|

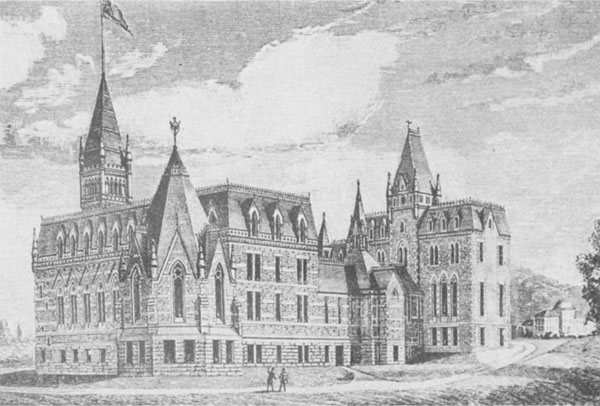

80

Presbyterian College, McTavish Street, Montreal, Que.

Constructed: 1876; wings, 1881

Material: stone

When the library and student residence were added to the main edifice in

1881, the Presbyterian College of Montreal became a complex of several

Gothic Revival buildings laid out around a central chapel. Certain

typical features, eclecticism and picturesqueness can be seen in the

design of this college. The gable roof is replaced by the typical

mansard roof of the Second Empire style and the towers have a pavilion

roof flanked by miniature turrets often associated with Castle Gothic.

The presence of the library in the form of a chapter house is an element

that returned to some colleges at the end of the 19th century. The

polygonal shape of this element, as well as the sharp roofs of the other

three towers in the complex created a pleasing contrast with the

regularity of the main body. Only the 1881 edition remains today; it is now

an integral part of the campus of McGill University.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "Addition to the

Montreal Presbyterian College," Vol. 23, No. 22 [June 18, 1881], p.

396.)

|

81

Normal School, Queen Street, Fredericton, N.B.

Constructed: 1878 (demolished)

Material: brick

On each side of this building there is a projection that appears to be

an attempt to offset the massiveness of the structure. A similar attempt

at movement is more freely expressed in the roof, which boldly combines

the mansard and the pavilion and is decorated with cast-iron cresting.

The variety of forms is also combined with a polychrome wall effect

produced by contrasting red brick and grey stone stringcourses and

voussoirs. In a building like this, the use of Neo-Gothic features,

particularly in the entrance arches, is associated with elements of

other styles to produce an overall composition inspired by a desire for

variety in both forms and stylistic associations.

(New Brunswick Provincial Archives.)

|

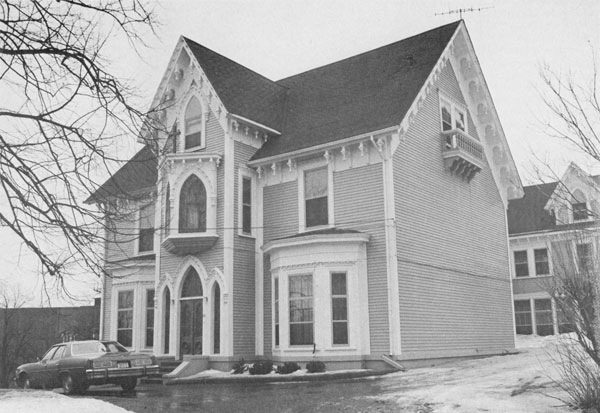

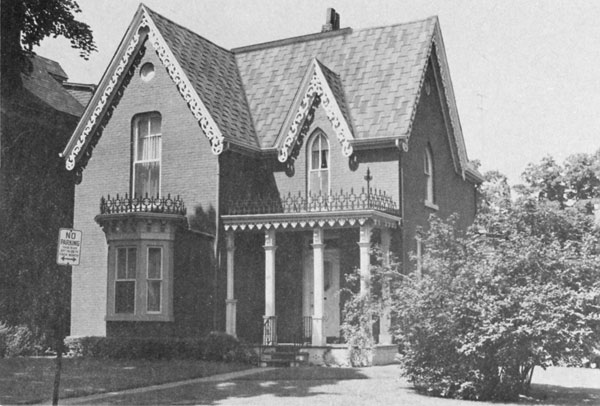

82

Burpee House, 101 Burpee Street, Saint John, N.B.

Constructed: ca. 1865

Material: wood

When this residence was built, it was a villa in a vast country estate on

the outskirts of the city. With its two-and-a-half storeys, Burpee House

was on a grander scale than most Gothic Revival houses in the Atlantic

provinces. The fašade has three bay windows — a feature that was

often characteristic of Gothic Revival houses in the Maritimes. From the

High Victorian Gothic style, it drew its vertical proportions and a

freedom of expression seen in a series of pendants under the eaves

— a pleasing substitute for the fretwork fascia boards usually

associated with the Gothic Revival house.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

83

House in Rothesay, N.B.

Constructed: ca. 1880

Material: wood

This house is a good illustration of how the evolution of forms toward

the end of the 19th century affected the expression of the Gothic

Revival style in New Brunswick domestic architecture. The proportions

clearly indicate a preference for verticality; also, under the influence

of a taste for picturesqueness the rectangular block of the house is

broken up by the sharply projecting elements of the central frontispiece

and the decorative gables on either side of it. However, these

differences are not enough to overcome the balance and harmony

underlying the vernacular architecture of the Atlantic provinces

throughout the 19th century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

84

55 William Street, Yarmouth, N.S.

Constructed: ca. 1870

Material: wood

In Canadian domestic architecture, the High Victorian Gothic fashion

generally led to changes in the treatment of traditional prototypes

without resulting in the construction of truly innovative houses in

terms of plans and proportions and the handling of the decorative

repertoire. Nevertheless, some houses like this one stray further from

the beaten track. Here, there is a definite taste for multiple

projections that break up the traditional compact volume. Unbalanced

effects also strike the eye; the very steep roof almost covers two

storeys, creating a striking contrast with the modest height of the

ground floor. Angular effects are sought out in the handling of details,

such as the treatment of the window frames. Only the clapboard siding is

reminiscent of the calm balance of earlier prototypes.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

85

21 Richview Road, Etobicoke, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1875

Material: brick

Although the chromatic effects of late 19th century brick houses in

Ontario remain relatively conservative, a few examples show some degree

of fantasy. This house, for example, is brightened by a border of

trefoil patterns in keeping with the Gothic Revival repertoire. Also,

its imitation corner piers have a geometric aspect that shows a freedom

of interpretation of traditional motifs. The horizontal scar over the

ground-floor bay shows that a veranda once ran across the front.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

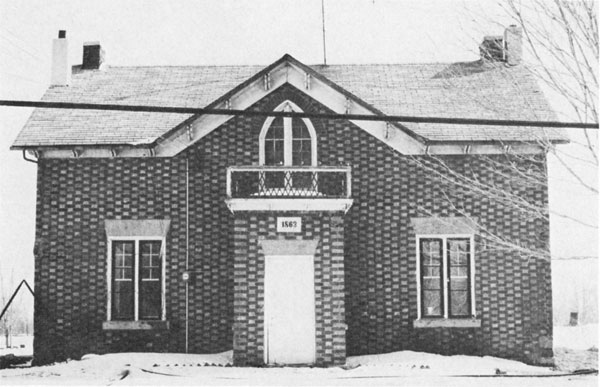

86

108 Albion Street, Brantford, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1875

Material: brick

A few features in the design of this house show how the High Victorian

Gothic style occasionally animated the type of house known as the

Ontario Cottage. The building retains an earthbound arrangement. Its

association with the Gothic Revival is based primarily on the pointed

window design and the finial through the peak of the small decorative

gable. However, the contemporary taste for polychrome walls is seen in

the yellow bricks around the bays and the border pattern along the

eaves.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

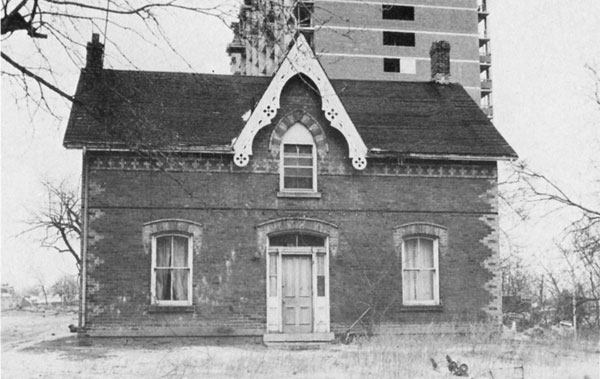

87

House in Milford, Prince Edward County, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1863

Material: brick

This house is of particular interest because of its fanciful fašade in

which red bricks are alternated with yellow bricks to create a

checkerboard effect. This interest in polychromy was apparently

encouraged in Ontario by a wave of British immigration during the second

half of the 19th century. The enclosed porch is also an indication of

British influence. Although the Canadian climate would appear to have

required this type of entrance, it had never been very popular in this

country. On the other hand, Loudon's Encyclopedia contains houses with

small entrance porches like this in the form of a compact block against

the centre of the building.

(Canadian Inventory c/Historic Building.)

|

88

Earnscliffe, Sussex Drive, Ottawa, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1857

Material: stone

This residence was first erected by John Kinnon, who was the son-in-law

and partner of Thomas McKay, one of the most active master masons of

Ottawa's early days. But the building is associated more with John A.

Macdonald, who bought it in 1883 and lived in it until his death in

1891. Since 1930, this house has been the home of the British High

Commissioners.

Earnscliffe is one of the most refined examples of the L-shaped Gothic

Revival house. Its general appearance retains the characteristic

reserve of Ottawa domestic architecture. The handling of proportions

gives the composition a feeling of great stability which is heightened

by the strongly three-dimensional effect of the Gothic Revival motifs:

drip mouldings, fretwork roof trim, pendants and bay windows.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

89

90 Emerald Street, Hamilton, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1875

Material: brick

In Ontario, the L-shaped house proved to be as popular in the city as in

the country. This example is treated with all the elegance and

conservatism of Hamilton middle class houses. Its rather imposing scale

is heightened by ample fenestration. The lively motifs on the veranda

and the bay window add vitality to the exterior composition.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

90

413 King Street West, Brockville, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1885

Material: brick

A definite taste for polychrome brick spread through Ontario in the last

decades of the 19th century. This influence is seen here on an L-shaped

house with proportions that create the vertical thrust fashionable at

that time. As in most houses of this type in Ontario, the polychrome

effect is reduced to a single contrast between details of yellow brick

and the surrounding red brick walls.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

91

76 Main Street East, Ridgetown, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1875

Material: wood

The builder of this house definitely had a penchant for the

picturesque. The exterior composition has rich, varied effects like those

proposed in the 1870s by the drawings in the architectural sections of

American periodicals, The L-shaped plan is set off by the entrance and a

mansard-roofed tower placed at the point of intersection between the two

wings. These two elements are highlighted by a veranda with finely

worked columns. Other decorative details are drawn to a great extent

from the formal repertoires of the Gothic Revival and Second Empire

styles, with a slight preference for sensual Second Empire roundness.

Finally, the varied forms and motifs are heightened by the polychrome

effects of the roofing shingles.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

92

The Price houses, 2138-1246 Brunswick Street, Halifax, N.S.

Architects: J.A. Mitchell and Edward Elliott

Constructed: 1873-74

Material: brick with sandstone detail

In 1873, a philanthropist named William P. West offered the parish of

the Church of the Redeemer the lands required to build the church of

that name and its rectory (2138 Brunswick Street). The following year,

West bought two more adjacent lots and had two houses built with the

same design as the rectory and donated the proceeds from their rental

to the vestry of the Church of the Redeemer. Both of the architects for

these houses were from Boston and they seem to have drawn their

inspiration from the famous Back Bay area of their home town, which was

at about the same time being built up with elegant mansard-roofed town

houses. In Halifax, the Neo-Gothic details on these Second Empire houses

associates them with the nearby church.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

93

144 Military Road, St. John's, Nfld

Constructed: ca. 1875

Material: wood

This house is a good illustration of the noncommittal approach which was

characteristic of the way this style was interpreted in this region.

This spacious house has the asymmetrical L-shaped plan so popular at

that time in other provinces in the country and its proportions indicate

an early preference for verticality. Ornamentally, the house uses a

contrast between the clapboard sides and the front with its

board-and-batten fašade combined with the two strips of ornamental

boarding of the Stick Style. Only the gable windows retain the pointed

Gothic effect.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

|