|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 25

Gothic Revival in Canadian Architecture

by Mathilde Brosseau

Illustrations and Legends

94

St. James-the-Less Chapel, St. James-the-Less Cemetery, Toronto,

Ont.

Constructed: 1857

Architect: Frederick Cumberland

Material: stone

It was certainly the prestige won by his St. James Cathedral commission

that enabled Frederick Cumberland to obtain the commission for the

funeral chapel in St. James Cemetery as well. Inspired by both the

highly picturesque quality of the site and the new direction of the

Gothic Revival style, Cumberland went into a more thorough exploration

of the expressive possibilities of its repertoire of forms. The chapel

is located on a slight rise, which it dominates with the upward thrust

of its spire. In addition, the composition develops a certain tension in

the treatment of the various elements of the plan: contrasts between

very low walls and plunging roof slopes — between powerful, heavy,

earthbound forms and other lighter, airier shapes — between the

short, pyramidal base of the bell tower and the sweep of its spire

— between the stocky tower flanked by a massive buttress and the

open volume of the the porch.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

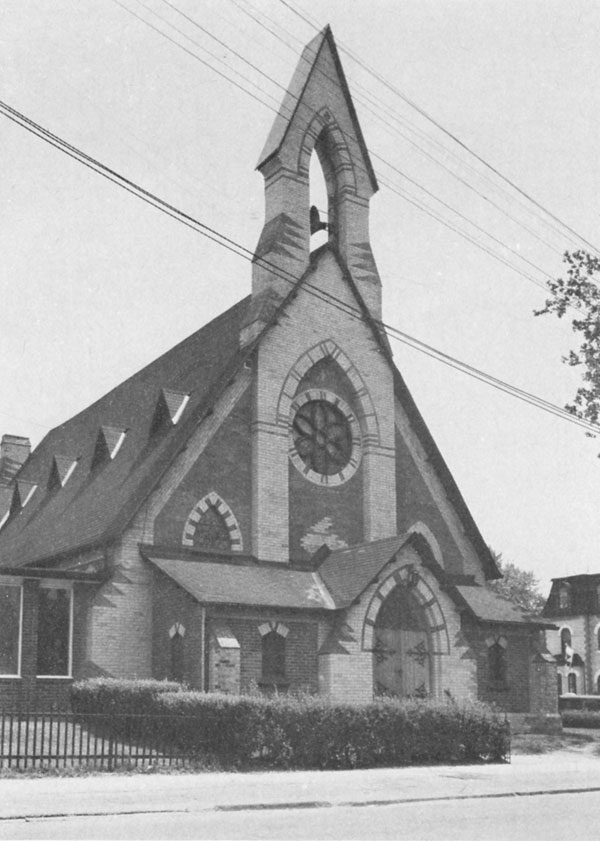

95

St. Peter's Anglican Church, Carlton Street, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: 1865

Architects: Henry Langley and Thomas Gundry

Material: brick

St. Peter's again reproduces the typical profile of the small 13th

century medieval churches, the stepped bell turret on the front, the

side porch and the chancel attached to the end of the nave. However, in

the case of St. Peter's, the architects worked with the proportions with

a view to creating visual effects, whereas they would probably have

attached more importace to harmony and balance fifteen years earlier.

The exterior design shows a desire to integrate the principle of

polychromy: for certain strong points in the composition, such as the

frontispiece, the angle buttresses and the façades on the small porches,

the architects used a yellow brick in sharp contrast with the other red

brick wall surfaces. On a smaller scale, these contrasts are reproduced

over the windows and in the structure of the bell turret.

Originally, the small front porch, which was much less salient than

shown here, was more in keeping with the overall design; the small

adjacent structures hiding part of the windows were also later

additions. The need for expansion also led to the addition of

transepts.

(Photo: G. Kapelos.)

|

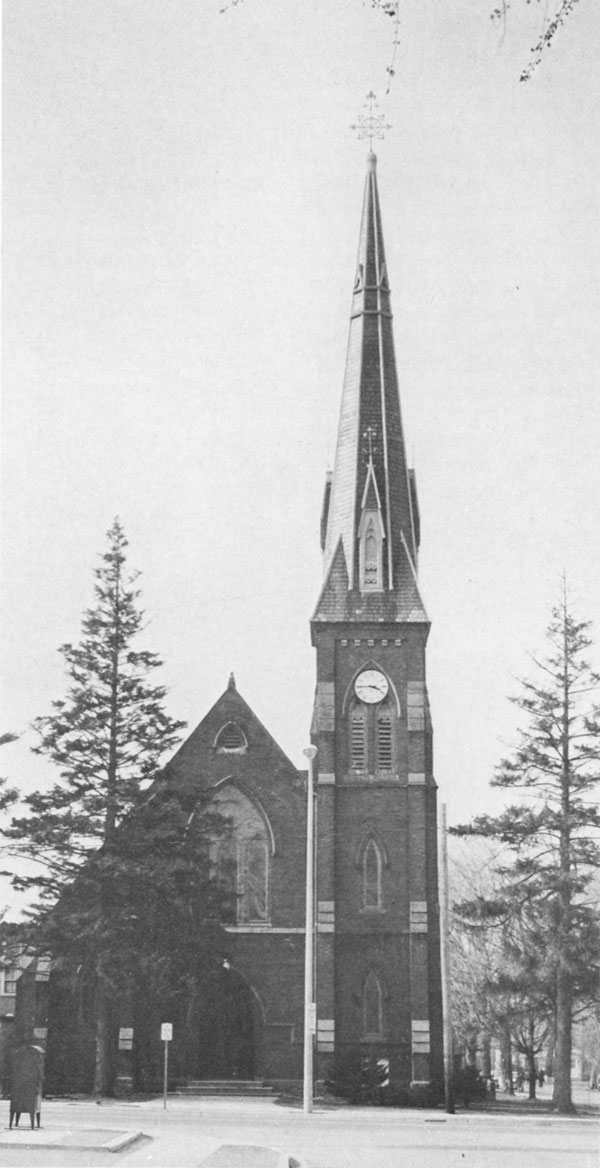

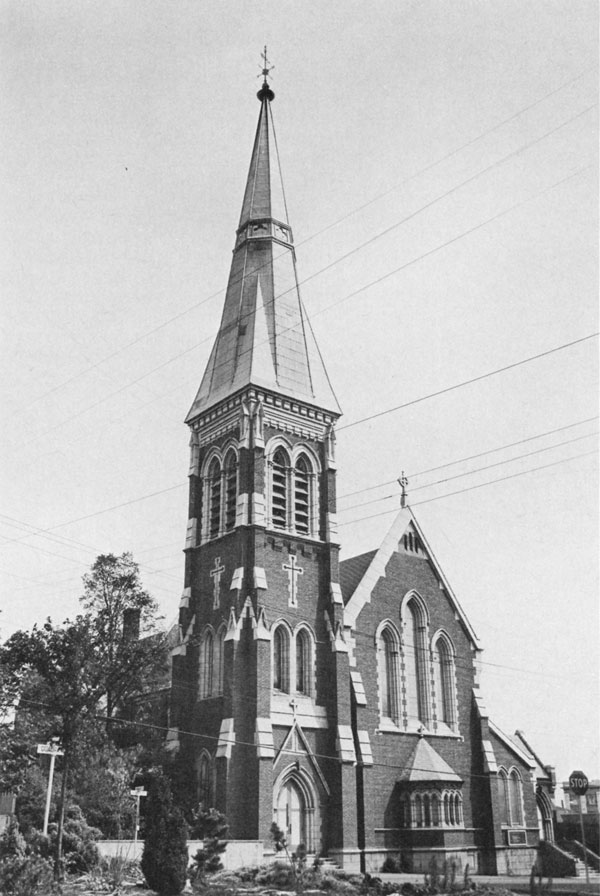

96

All Saints Anglican Church, 300 Dundas Street West, Whitby, Ont.

Constructed: 1865-66

Architects: Henry Langley and Thomas Gundry

Material: brick

In terms of arrangement of forms, All Saints Church closely follows the

requirements of the Cambridge Camden Society. In terms of decoration,

particularly in the window design, it remains faithful to the formal

repertoire of the 13th century. But an innovative effect is seen in the

treatment of volume, which plays on the contrast between the wide

triangle of the nave and the slenderness of the adjacent spire, and

also in the use of a simplified form of polychromy indicating the

assimilation of the ornamental principles cherished by Ruskin.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

97

First Baptist Church, 5 Pine Street, Brockville, Ont.

Constructed: 1878

Material: stone

A building like the Brockville Baptist Church places the observer in

the presence of the sensitivity that animates the best works of the

Victorian period. This church breaks with an architectural tradition

that, for a long time, had favoured a compact building with proportions

creating an effect of equilibrium and repose. Here, the basic volume

splits into five distinct masses that nevertheless retain their unity

through their interpenetration and plasticity. The split stone walls do

not lend themselves to polychrome effects, but the gay coloured shingle

effects of the roof contribute to the animation of the overall design.

In order to give more vitality to the composition, the shape and

arrangement of Gothic Revival motifs were varied from one mass to

another, although care was taken to include reminders to reinforce the

overall cohesion. The church is even more striking because of the key

position it occupies on the courthouse square in Brockville, one of the

most beautiful urban spaces in Ontario.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

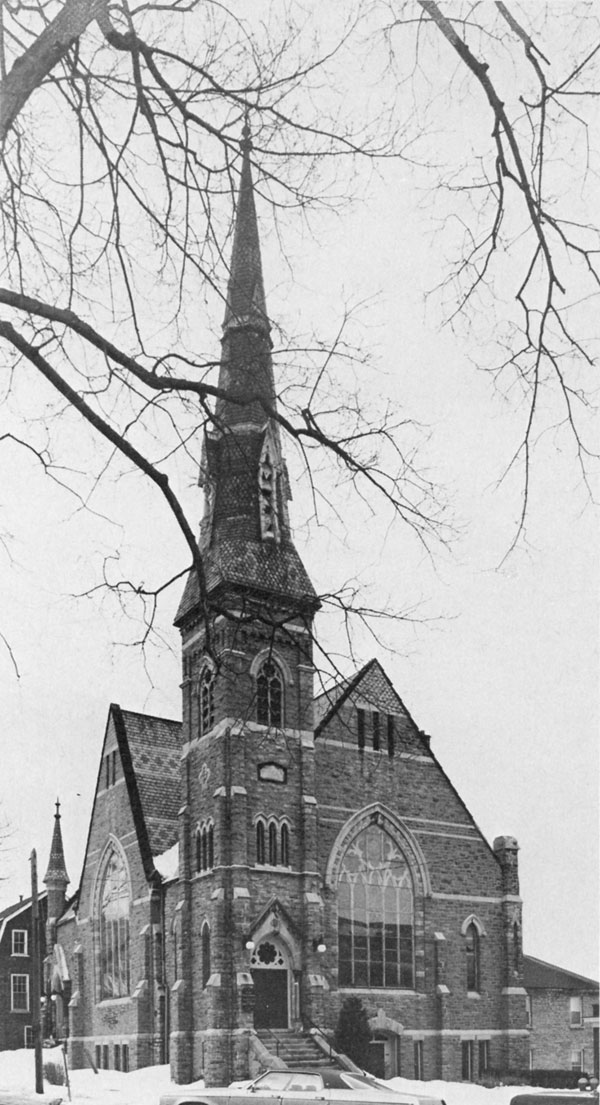

98

First Presbyterian Church, 10 Church Street, Brockville, Ont.

Constructed: 1878-79

Architect: J.P. Johnston

Material: stone

Although a less generous composition than that of the Baptist Church

(Fig. 97), First Presbyterian Church also makes ample use of

interpenetrating forms and texture and polychrome effects, and it also

aims at a virtuosity of form that is particularly visible in the skyward

sweep of the spire.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

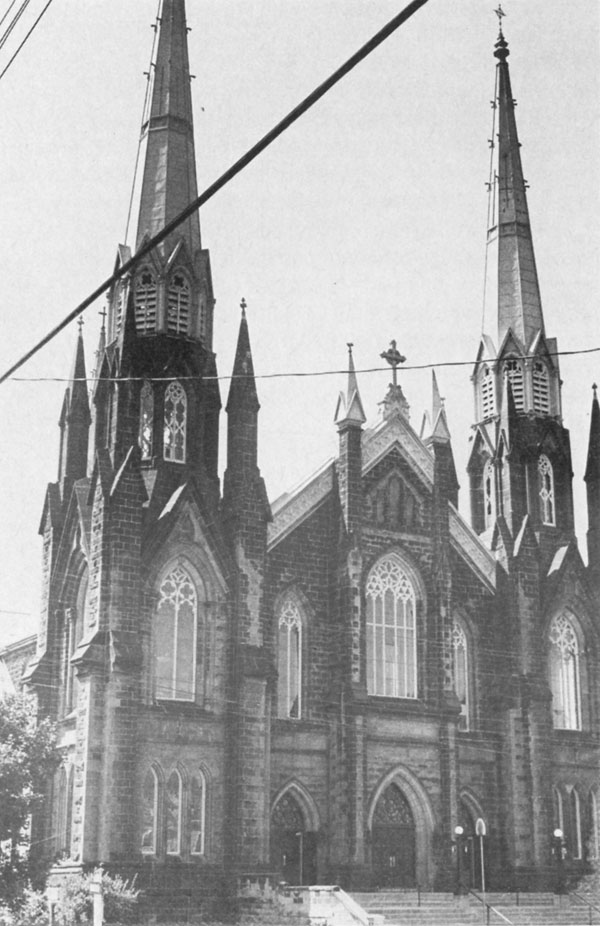

|

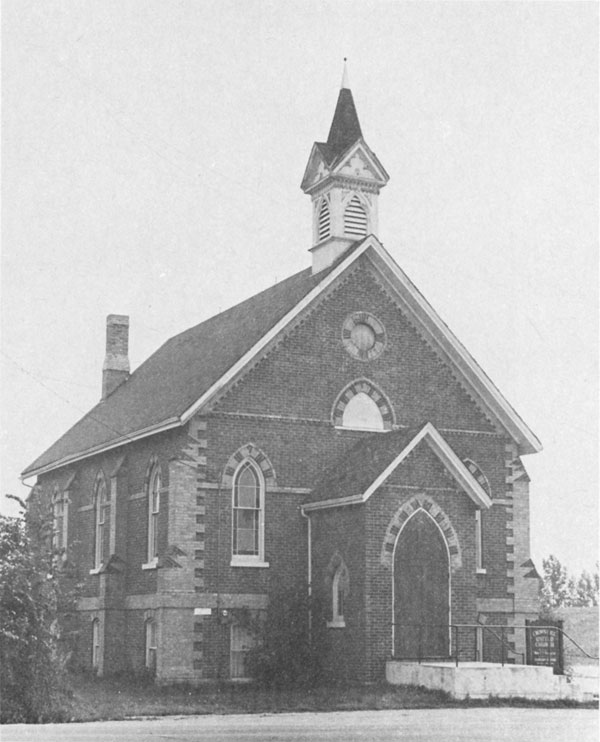

99

United Church, Crown Hill, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1880

Material: brick

The very simple scheme of this church perpetuates a tradition rooted in

the vernacular architecture of the country from the beginning of the

19th century. However, various elements associate the building with the

High Victorian Gothic: first, a raised basement giving a vertical thrust

to the building and then the use of a brick colour contrast to highlight

the bay details.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

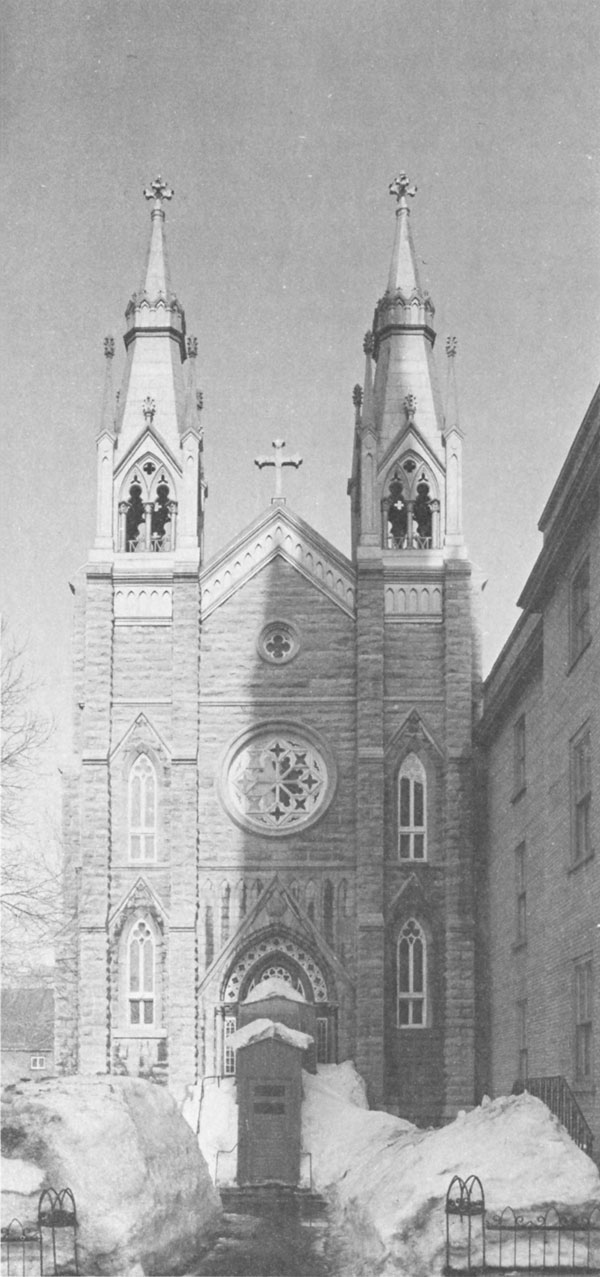

100

Chapel of Notre-Dame du Sacré-Coeur, 69 Sainte-Ursule Street, Quebec,

Que.

Constructed: 1909-10

Architect: François-Xavier Berlinguet

Material: stone

The double tower principle is usually seen on large urban churches, but

in this case it is applied to a chapel of rather modest dimensions. This

may result from a desire to reproduce the characteristics of a

prestigious church on a smaller scale. However, this basic inspiration

must have been quite vague, since the choice and treatment of details

are in no way exotic. On the other hand, the rigidity of the façade is

characteristic of the architect François-Xavier Berlinguet, as it is

found in several of his works.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

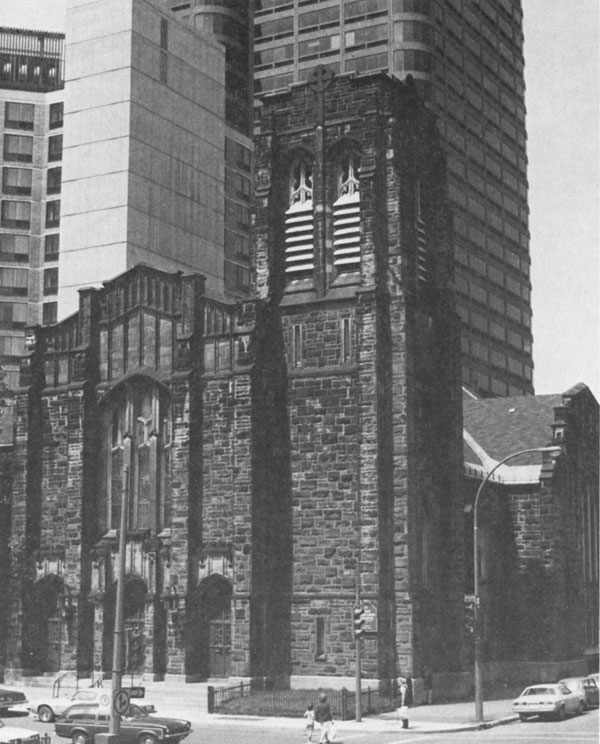

101

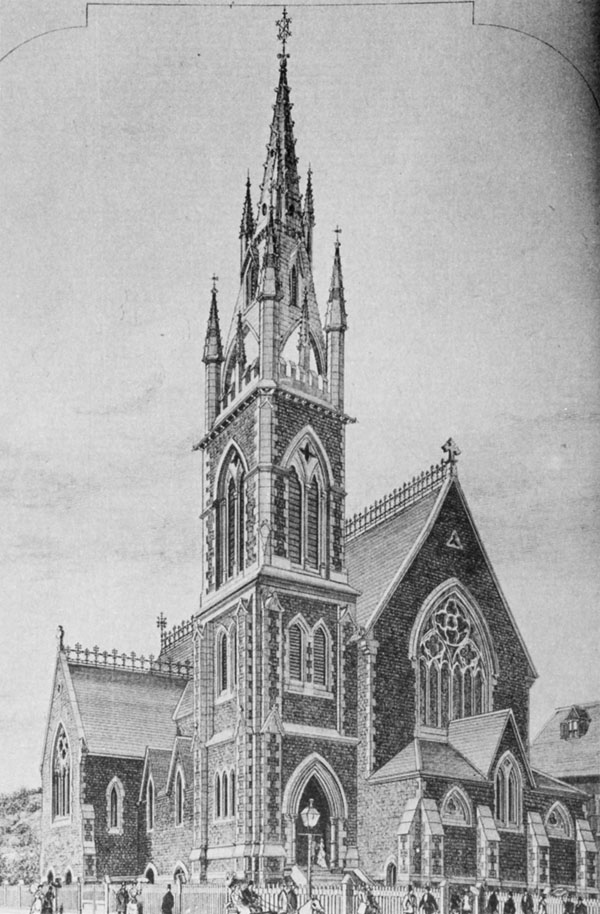

Saint Martin's Anglican Church, Saint-Urbain Street, Montreal, Que.

Constructed: 1874 (demolished)

Material: stone

St. Martin's Church concurs with the Catholic churches of the region in

the use of split stone, which was very widespread at that time. The

general articulation is more in keeping with the contemporary taste for

a vigorous, aggressive Neo-Gothic style in search of asymmetry and

exuberant formal effects. The raised basement allowed for the

installation of Sunday School classes — a common practice in

Protestant churches at that time.

(Canadian Illustrated News, "St. Martin's

Church, Upper St. Urbain Street, Montreal," Vol. 13, No. 13 [April 8,

1876], p. 234.)

|

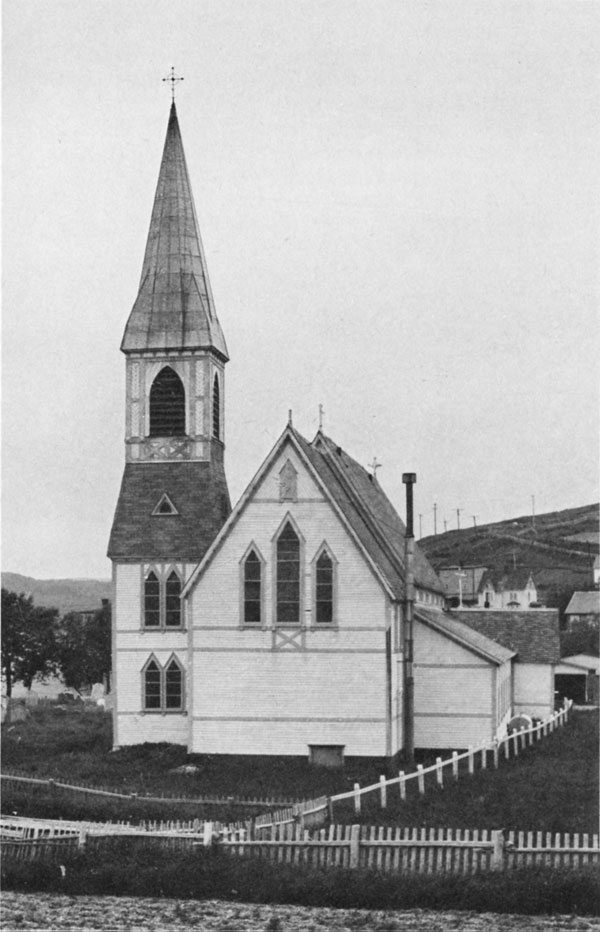

102

St. Paul's Anglican Church, 1 Church Street, Trinity, Nfld

Constructed: ca. 1894

Material: wood

St. Paul's Anglican Church is a modest rendition of the spirit of High

Victorian Gothic forms. The theories of the Cambridge Camden Society

still govern the arrangement of masses. However, the forms are slightly

more aggressive in the relatively steep angle of the gables and the

thrust of the spire. In addition, the building design is steeped in

Maritime architectural effects such as the half-timbering features of

certain ornamental boards on both the walls of the bell tower and on the

chancel façade. These are ornamental effects found primarily on the

wooden domestic buildings of Newfoundland toward the end of the 19th

century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

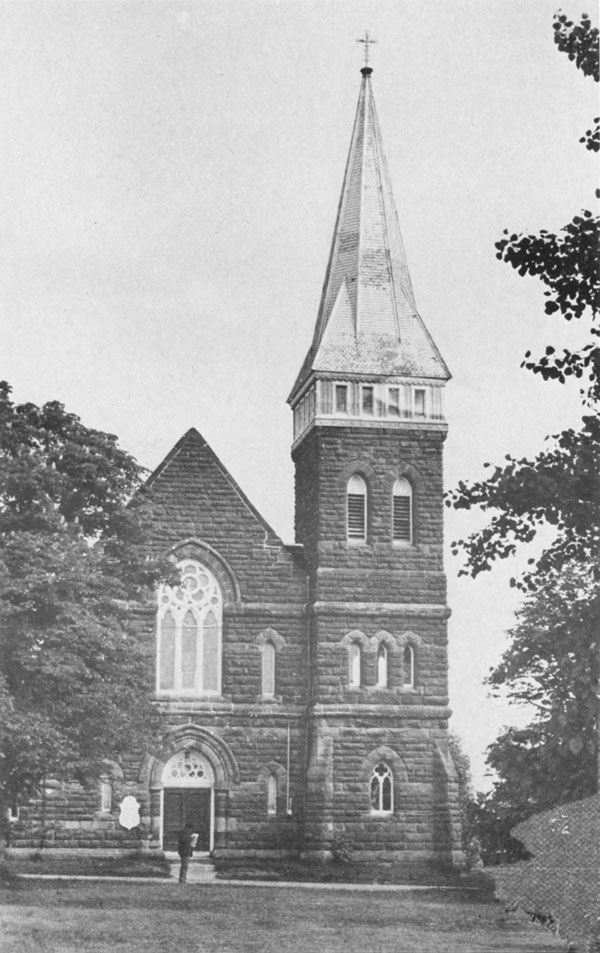

103

Catholic Church, Sturgeon, P.E.I.

Constructed: 1888

Architect: William Critchlow Harris

Material: stone

Despite its Gothic fenestration, the Sturgeon Catholic Church bears the

mark of a Romanesque influence. The sandstone walls are made up of very

large blocks that decrease in size as they move upward; the surface

treatment includes protuberances that contribute to a powerful,

monumental impression. The simple, infrequent details are in keeping

with the immobile quality of its masses. Despite an articulation that is

typical of High Victorian Gothic churches combined with pointed

fenestration, the Sturgeon church is more in keeping with the

Neo-Romanesque spirit promoted by the American architect Henry Hobson

Richardson, than the spirit of High Victorian Gothic.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

104

St. Dunstan's Catholic Basilica, 61 Great George Street, Charlottetown,

P.E.I.

Constructed: 1914-18

Architect: J.M. Hunter

Material: stone

The architect designed a stone church of imposing dimensions with a

particular character resulting from the intricate composition of the

façade dominated by two towers. A forest of pinnacles grows out of the

façade and towers, producing an effect that is reminiscent of the

profuse treatment of the famous cathedral of Milan. The pinnacles and

the highly intricate window tracery indicate an inspiration drawn from a

late Gothic phase — Flamboyant Gothic. Built at a time when a

taste for monumentalism and simplicity of volumes was already

developing, the Charlottetown Basilica remains faithful to a

picturesque approach derived from the end of the 19th century.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

105

St. Paul's Anglican Cathedral, 1 McIntyre Street, Regina, Sask.

Constructed: 1895

Architect: Frank H. Peters

Material: stone and brick

St. Paul's Cathedral has a modest, austere appearance resulting from its

dimensions, its arrangement of forms and its architectural

ornamentation. The building is built on fieldstone foundations that

create a pleasing contrast with the red brick walls. The proportions

amplify the roof to a considerable extent and the plain volume of the

roof harmonizes well with that of the sturdy tower. To meet the needs of

a rapidly growing parish, the church vestry decided to place the

construction of the transepts and chancel in the hands of architect W.R.

Riley in 1905. He integrated them perfectly with the original

design.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

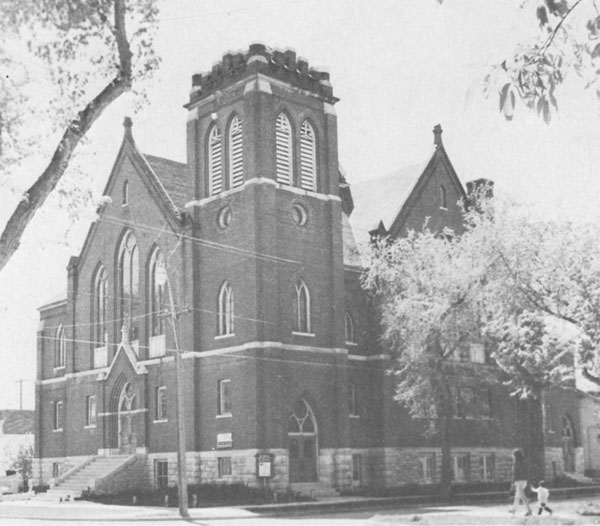

106

St. Giles United Church, 289 Burrows Street, Winnipeg, Man.

Constructed: 1907

Material: brick

This church stresses an asymmetrical arrangement of forms, but it lacks

the inventive freedom and taste for daring contrasts of form that

animate the most successful High Victorian Gothic compositions. The

composition of St. Giles Church is faithful only to the letter of the

style, not its spirit.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

107

St. John the Divine Church, 1611 Quadra Street, Victoria, B.C.

Constructed: 1910

Material: brick

It is difficult to draw a chronological line between works belonging to

the formal approach of the High Victorian Gothic style and those

influenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. A few buildings

affected by the academic tradition of the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts appear during the first decade of the 20th century,

but others such as St. John the Divine church continue to show the

influence of High Victorian Gothic forms. The designer of this church

continues to stress vertical proportions, relatively rich ornamentation

and highlighting with grey stone polychrome accents against a red brick

background.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

108

St. Andrew's Cathedral, Blanshard Street, Victoria, B.C.

Constructed: 1892

Architects: Maurice Perrault and Albert Mesnard

Material: brick

On first sight, it is surprising to find that the commission for this

large church in Victoria was awarded to a Montreal architectural firm.

However, this is explained by the reputation of Perrault and Mesnard in

religious architecture. For St. Andrew's Cathedral, the architects

remained faithful to the double tower principle, but they gave it more

picturesque effects than those of most churches of this type in Quebec.

The composition is asymmetrical in the treatment of its towers, of

which only one has the vertical sweep that is so characteristic of High

Victorian Gothic. In addition, there is another visual variant in the

treatment of the outer walls. The principle of construction polychromy

is present in the form of grey stone stringcourses inserted in the

brick masonry; textural effects are also seen in the beehive designs

worked into various points in the wall surfaces and providing a contrast

with the rhythm of the roof tiles on the two bell towers.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

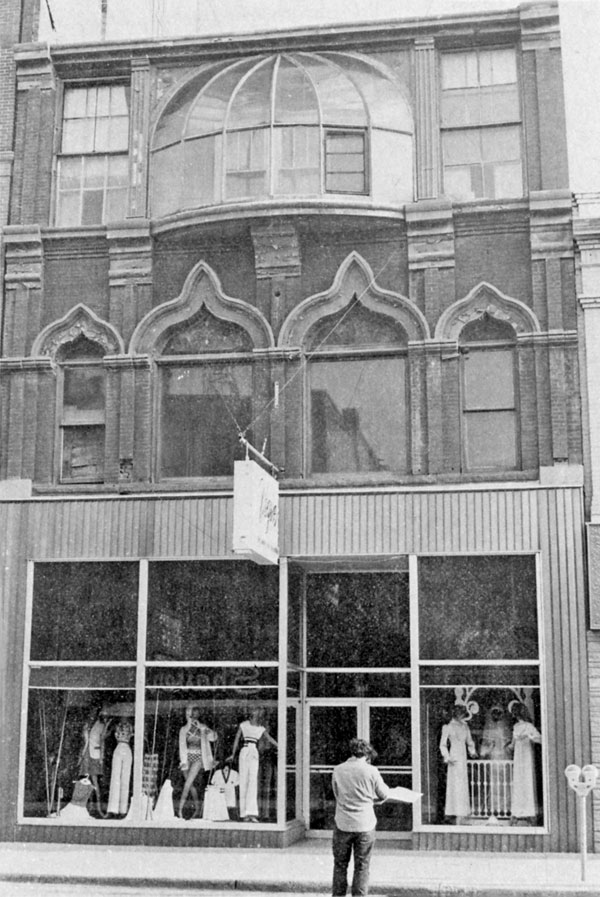

109

836 Rosser Avenue, Brandon, Man.

Constructed: ca. 1910

Material: brick

Although this building very probably dates back to the first decade of

the 20th century, it still shows the taste for fanciful forms found in

late 19th century architecture. The upper stories are punctuated by

pilasters that are partially covered on the second storey by Neo-Gothic

windows with something of an oriental influence in the curves of their

openings. On the third storey, the Gothic Revival touches give way to

windows with a maximum of glass surface. However, the graceful tracery

of the bay window in the centre provides an interesting counterpoint

with the two wide Neo-Gothic windows on the second storey.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

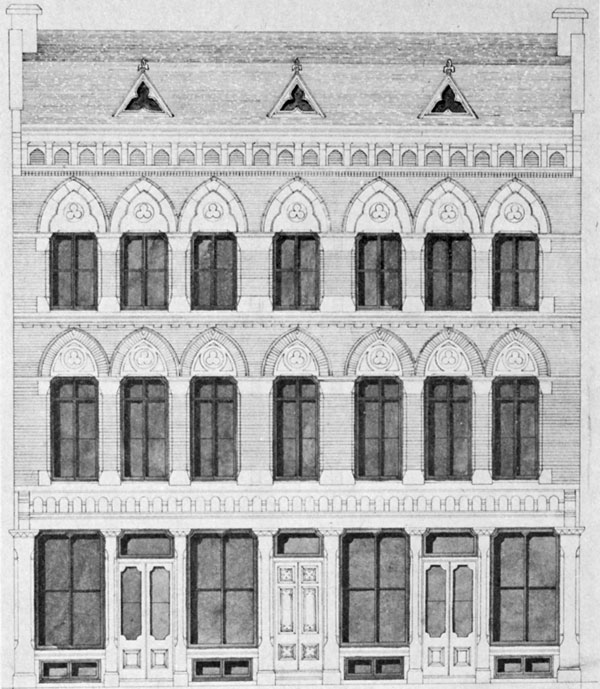

110

James Brennan Stores, Saint-Jean Street, Montreal, Que.

Architects: Hopkins, Lawford and Nelson (as attributed by the

Quebec National Archives)

Material: brick and cast-iron

The articulation of this building divides it into three horizontal

registers. The problem of adapting the fenestration to the Gothic

Revival style was solved by surmounting the rectangular windows with a

sort of blind arch containing decorative tracery based on a trefoil

motif. In addition, the wall surfaces between the windows are

highlighted by a series of pilasters that receive the springings of the

broken arches over the windows. This project had the merit of blending

the building into a cityscape of older commercial buildings while

providing the eye with a Neo-Gothic "disguise" that was quite

acceptable to contemporary tastes.

(P. Bédard, N. Cloutier and A. Giroux, "Inventaire des

plans architecturaux des Archives civiles du Québec à Montréal,"

History and Archaeology/Histoire et archéologie, No. 4, Vol. b

[1976], p. 99.)

|

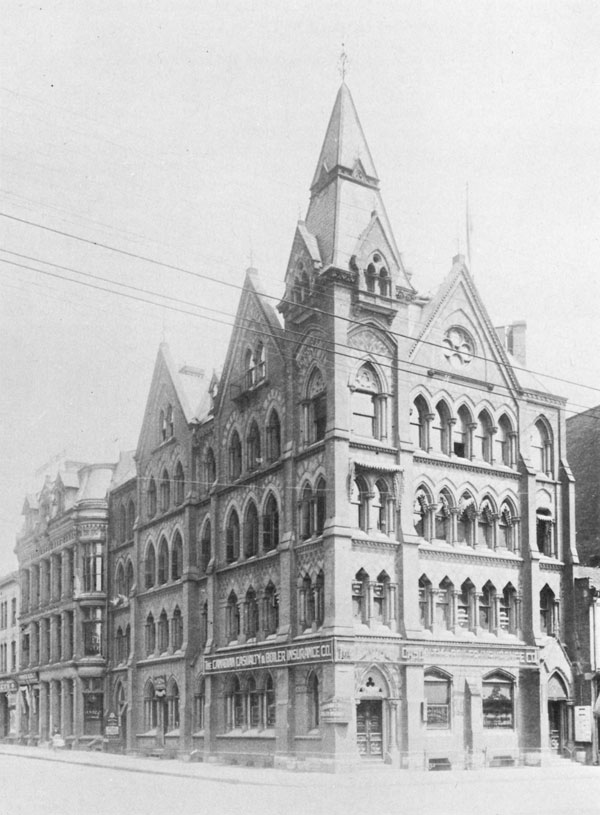

111

Equity Chambers, Adelaide and Victoria Streets, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: ca. 1878 (demolished)

Material: brick

The Equity Chambers office building took maximum advantage of

picturesque possibilities; the eye of the observer was immediately

drawn by the lively silhouette of the building and the corner tower and

a roofline broken up by high ornamental gables. In the walls, this

animation took the form of varied window arrangements interrupted at

irregular intervals by buttresses running from top to bottom of the

building. The wall surface treatment adhered faithfully to the principle

of construction polychromy advanced by Ruskin. Coloured materials

traced out geometric and trefoil patterns that were highly reminiscent

of the visual effects on Venetian Gothic palaces. The windows,

particularly those of the second floor, illustrate this analogy; they

had broken arches without frames and were separated by small columns

topped with delicate capitals.

(Public Archives Canada.)

|

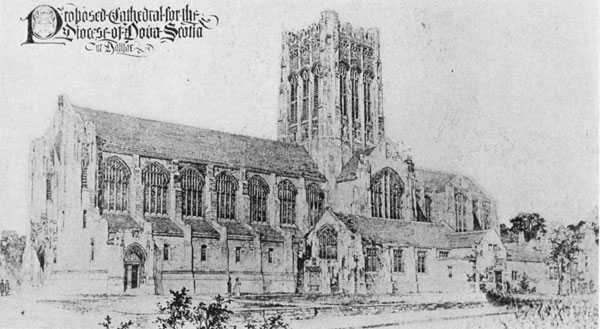

112

All Saints Anglican Church, 5732 College Street, Halifax, N.S.

Constructed: 1906

Architects: Ralph Cram and Bertram Goodhue

Material: stone

This church was built with stone from the Halifax region and complied

with the final design except for the tower, for which only the base was

built. With a view to creating an impression of order, monumentalism and

grandeur in accordance with the tradition of the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts, the architects chose the formal repertoire of the

late Gothic period, the Perpendicular Gothic of the 15th century; thus

the use of broad windows with highly visible ornamental tracery.

Contrary to the High Victorian Gothic spirit, the outline of forms is

simple and the emphasis is placed on an impression of calm regularity,

which is enhanced by the horizontality of the composition.

(Montgomery Schuyler, "The Works of Cram, Goodhue and

Ferguson, a Record of the Firms most Representative Structures

1892-1910," Architectural Record, Vol. 29, No. 1 [Jan. 1911], p.

18.)

|

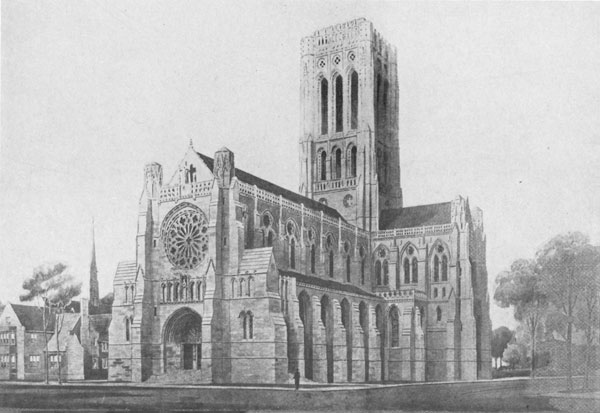

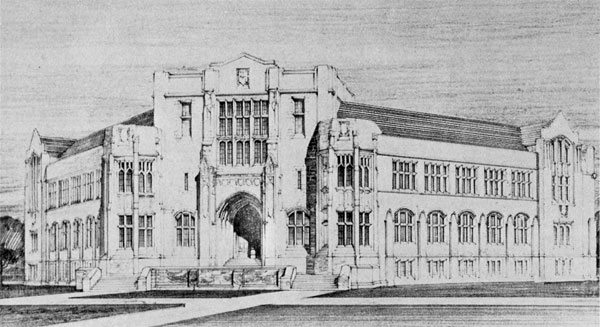

113

Project for St. Alban the Martyr Anglican Cathedral, 100 Howlands

Avenue, Toronto, Ont.

Design: 1911

Architects: Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson

Material: stone

If this design for St. Alban's Cathedral had been built as planned, it

would have been one of the very first appearances of a new vision of the

Gothic repertoire in Toronto religious architecture. This illustration

of the exterior reveals a particular insistence on simplicity of form

and a powerful visual effect. This imposing smooth stone edifice

encompasses the various components of the plan (nave, aisles, transept

and chancel) in a geometric spatial arrangement leaving the horizontal

limits of the various roofs open to view. Emphasis is no longer placed

on the richness or picturesque effect of details or on bold formal

relationships, but rather on a highly organized spatial arrangement

combined with a preference for solemnity and repose in the forms. The

designers did not make any attempt at archaeological accuracy and chose

to draw free inspiration from medieval prototypes in order to convey

their own perception of forms. In this respect, the author of an article

on the Cram and Goodhue composition made the following observation: "An

effort has been made to epitomize the architectural impulse of the early

Middle Ages to reduce this to its simplest and most fundamental terms,

and then to vitalize the whole by the spirit of the twentieth century."

(Construction, "Cathedral of St. Alban the Martyr, Toronto,

Architects: Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson," Vol. 6, No. 1 [Jan. 1912], p.

50-58.)

|

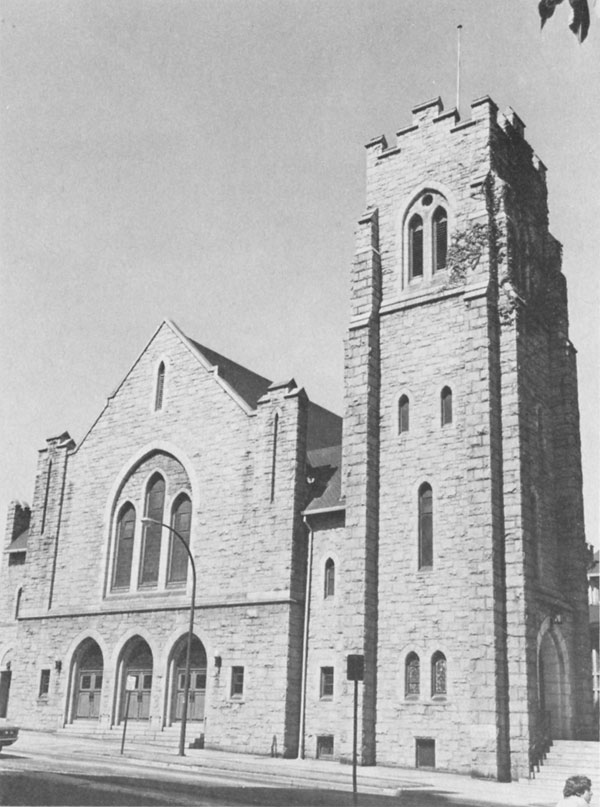

114

First Presbyterian Church, 3666 Jeanne Mance Street, Montreal, Que.

Constructed: 1914

Architects: Hutchison, Wood and Miller

Material: stone

Despite an asymmetrical façade derived from a style of articulation that

was very popular during the High Victorian Gothic period, this church

represents a considerable departure from the perception of forms proper

to that period in the evolution of the Gothic Revival style. As opposed

to the tension effect of High Victorian Gothic churches, this church has

a grandiose, solemn arrangement. The articulation of volume is almost

entirely based on pure, geometric forms. Apart from the simple outline

of the bays and the presence of a few ornamental panels, archaeological

motifs have almost disappeared from the wall surface leaving large

expanses of masonry untouched to emphasize the simplicity and power of

the design. The interior is arranged according to an auditorium plan,

which had regained favour since the end of the 19th century,

particularly in Presbyterian churches.

(Photo: M. Brosseau.)

|

115

First Baptist Church, 969 Burrard Street, Vancouver,

B.C.

Constructed: 1910-11

Architects: Burke, Horwood and White

Material: stone

This church was one of the first to introduce the Gothic Revival in the

Beaux-Arts manner to the city of Vancouver. Its design is an

arrangement of simple volumes that anchor the building to the ground by

the visual power of their mass alone. The taste for varied visual

effects found in the composition of High Victorian Gothic churches gives

way to a desire for monumentalism and grandeur. The simplicity (or even

monotony) of the decor is apparently one of the means used by the

architect to obtain a more solemn effect.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

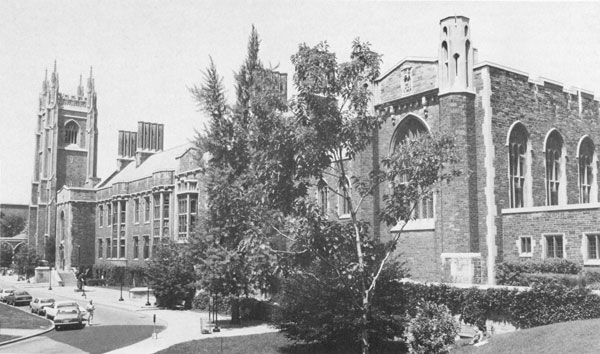

116

Hart House, University of Toronto campus, Toronto, Ont.

Constructed: 1911-19

Architects: Sproatt and Rolph

Material: stone

From the very first stages of the project, an intense collaboration

sprang up between the client, Vincent Massey, and the Sproatt and Rolph

firm. All three agreed on the choice of the Gothic repertoire in both

symbolic and practical terms thus permitting the harmonious additions to

the original plan, In this respect, Sproatt made the following remark:

"Collegiate Gothic is the one architecture developed for scholastic

work. It is a success and a joy. Why throw it away?" Partly as a result

of the discipline of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts tradition, the

architects were able to make a logical distribution of the various

activities in four wings surrounding a courtyard. The overall design

acquires a high degree of stylistic unity through the calm, monumental

impression it creates. There are several contributing factors: the

stress placed on masses rather than silhouettes, the horizontal lines

and the reduction of picturesque motifs to a minimum.

(Photo: G. Kapelos.)

|

117

Chemistry Building, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Sask.

Constructed: ca. 1920

Architects: David K. Brown and Hugh Valiance

Material: stone

The chemistry building is part of a second group of edifices built

during the 1920s. It is a good illustration of the stylistic effect the

firm gave to all the buildings on the campus. The Gothic Revival version

according to the principles of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts is

immediately identifiable. The yellow sandstone building is made up of a

main body flanked by two wings angled back from the central mass. This

perfectly symmetrical arrangement is made up of very simple volumes

that enhance the horizontality of the composition. A few Gothic

elements such as the Elizabethan gables, a few pointed bays and a series

of multiple mullion windows drawn from Tudor manors are superimposed

on this scheme.

(David Brown "The University of Saskatchewan,

Saskatoon," Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Vol.

1, No. 4 [Oct.-Dec. 1924], p. 109-13.)

|

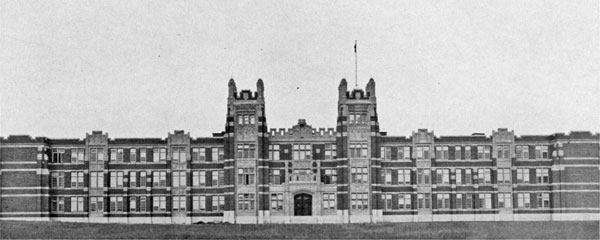

118

Institute of Technology and Art, Calgary, Alta

Constructed: 1922

Architect: Richard P. Blackley

Material: brick

The Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary is highly representative

of the general appearance of many schools built during the second and

third decades of the 20th century by the Departments of Education of

the various Canadian provinces. The building has a rectangular form that

has been extended further and further in either direction; its plan now

has only a relatively standardized distribution of functions on either

side of a stately vestibule. There are ornamental features on the

exterior and it retains a vague medieval inspiration that is lacking in

vitality, being limited to crenelations and a pointed arch marking the

entrance.

(Construction, "Institute of Technology and

Art, Calgary, Alberta, Architect: Richard P. Blackley," Vol. 15, No. 11

[Nov. 1922], p. 336.)

|

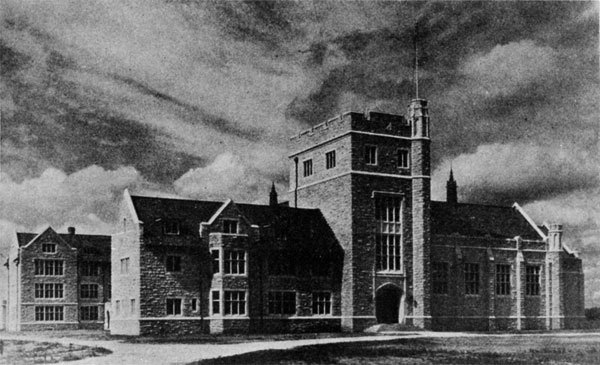

119

The Manitoba School for the Deaf, 500 Shaftesbury Blvd., Winnipeg,

Man.

Constructed: ca. 1920

Architect: John D. Atchison

Material: stone

When this building was opened in the early 1920s, it was used as a

school and residence for more than 200 young deaf mutes from the three

Prairie Provinces. The general plan, designed according to the hierarchy

propounded by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, distributes the various

functions of the edifice in an H-shaped scheme. This photograph shows

the main body dominated by a square tower erected in memory of the

school's founder. This is the most prestigious section, which was

designed to house the administrative offices (to the left) and the

chapel, which is identified from the exterior by the series of

buttresses. The decorative repertoire is made up of typical Tudor

features (multiple mullion windows, bay windows and parapet gables),

working them into a composition that gives priority to a national

spatial organization.

(Construction, "Manitoba School for the Deaf,

Winnipeg, Architect: J.D. Atchison," Vol. 16, No. 6 [June 1923], p.

193.)

|

120

The Second Government House, Wellington Street, Ottawa, Ont.

Constructed: 1916-19

Architects: John Pearson and Omer Marchand

Material: stone

The parliamentary committee in charge of the reconstruction of this

building stipulated that the new seat of Parliament should be in the

greatest possible compliance with the appearance of the original

composition, both in terms of masses and the choice of decorative motifs

and materials. Because of increased requirements, it was decided to add

a storey to the building and make a few alterations in the plan. The

photograph clearly shows that despite a similar articulation, the

general character of the design has been considerably modified. The

strength and energy of the picturesque forms of the first building give

way to an abstract touch that primarily stresses the highlighting of a

strict articulation of masses. In this context, the Gothic motifs

acquire a greater symbolic value. The new atmosphere of this composition

owes much to the influence of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Omer

Marchand was one of the first Canadian architects to demonstrate skill

in the Beaux-Arts manner as a result of a prolonged training

period in the famous Redon and Laloux shop in Paris.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

121

Park Building, 3414-3418 Park Avenue, Montreal, Que.

Material: stone (façade), brick (other sides), cast-iron (ground

floor)

Here we see the Gothic Revival style in the Beaux-Arts manner

applied to the façade of a commercial building. On the ground floor,

broad windows are outlined by a pointed arcade. The two upper stories

are regularized by fenestration based on the arch and spandrel system.

The cornice of the building boldly combines a border of geometric

patterns with gargoyles that appear to look down on passersby. This

façade is executed in smooth, nearly white stone as recommended by

Beaux-Arts teachings.

(Photo: M. Brosseau.)

|

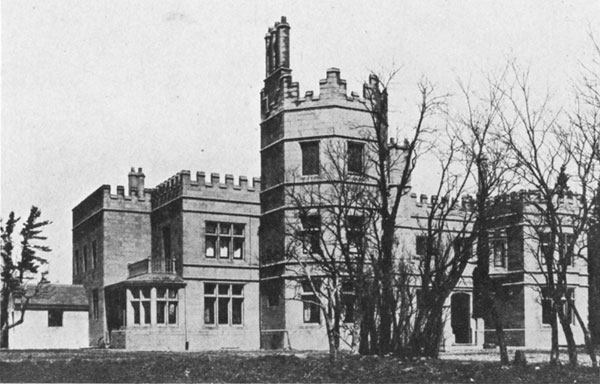

122

Glengrove or Ainsley House, 100 Glen Grove Street West, Toronto,

Ont.

Constructed: 1909 (demolished)

Architect: George W. Gouinlock

Material: stone

The archaeological source of this composition is recognized at once: the

Tudor period in England. This is indicated by the pseudo-fortress

appearance created by a sharply crenelated roofline, a main tower with

tall ornamental chimneys and windows broken up by multiple mullions. The

architect opted for the highly stylized aspect of a composition based on

the teachings of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts; thus the treatment of

the nearly white stone provides a very smooth surface in keeping with

the highly geometric character of the masses. In the final analysis, it

is probably the combination of the formal "signs" of a medieval

architecture and the academic handling of forms and materials that give

an impression of strangeness before a building like Ainsley House.

(Construction, "Residential Structure in 'Tudor' Design,"

Vol. 2, No. 9 [Sept. 1909], p. 51.)

|

123

Brenchley House, 3351 Granville Street, Vancouver, B.C.

Constructed: 1912

Architects: Samuel Maclure and Cecil Fox

Material: wood and stucco

This house is one of the most well-known examples of the Tudor house for

which the architect Samuel Maclure was renowned in both Victoria and

Vancouver. Like all buildings of this type, the house retains from the

Tudor period only the half-timbered effect produced by strips of wood

alternating with white stucco rectangular surfaces.

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

124

116 Roslyn Road, Winnipeg, Man.

Constructed: 1909

Architect: John D. Atchison

Materials: stone, brick, cement and wood

This is one of the many examples of houses derived from the

half-timbered structures of the Tudor period that were built in Canada during

the first decades of the 20th century. Needless to say, the structural

realism of the old half-timbered houses has been abandoned and the

architects retain only the rhythmic effect created by the beams. This

house combines a brick-faced ground floor with a second storey covered

with cement stucco and broad planks (no longer beams) which have been

fastened to battens before the stucco is applied. The anachronism of

this composition is indirectly expressed by the author of an article on

the construction of this house, who describes it as "a recent example of

the English half-timbered house built according to modern methods of

construction"!

(Canadian Inventory of Historic Building.)

|

|