|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 21

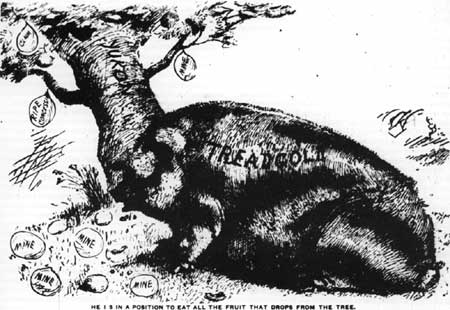

by Edward F. Bush Political Agitation and Journalistic Ferment, 1900-09(continued)The Concession Controversy The concession controversy was to muddy the political waters of the Yukon for over two years. Both the Nugget and the News were strongly committed against the practice while the Sun took a more moderate line. The issue hinged upon the government practice of granting large tracts of long-term leases to companies and syndicates for working creek gravel by hydraulic processes, requiring expensive equipment and abundant capital. The practice was held to be detrimental to the interests of the individual prospector and placer miner, without whom there would have been no gold rush and no Dawson. The largest concession was issued to an Englishman, A.N.C. Treadgold, who obtained from the minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton, rights to the richest creeks — Bonanza, Eldorado, Bear and Hunker. Treadgold's scheme was at once seen as a monopoly inimical to the interests of the individual miner. Before the lease was cancelled by order in council on 22 June 1904, at Treadgold's own request for want of the necessary capital, the press and the politicians of Dawson had plunged to their armpits in the melee.

The News was as militant as the Nugget on the subject; concessions for hydraulic operations on a large scale should only be granted when the ground was no longer rich enough for the placer miner. The News stated its opinion in a typical editorial of 19 April 1902. The object of keeping the ground idle is so that more claims will lapse and fall into the lease, and the condition will obtain until all the miners have deserted the district. If the intention is to give over the country to monopolists, well and good. The present methods will very effectually accomplish this; but if the country is to be developed by the individual miner compel the concession owners to get to work or take the ground away from them. [38] The Nugget referred to the Treadgold concession as "the greatest mining octopus that has ever fastened tentacles on Klondike." [39] On the other hand, the Sun opined that the whole concession issue should be suffered to die a natural death for the few still operative would lapse if their terms were not met. Agitation on the issue discouraged business and particularly capital. Leaving aside the concession controversy, which was to flare anew throughout 1903 and the first half of 1904, an editorial in the Nugget dated 19 August 1902 was a portent of the future. Dawson is undeniably quiet. There is lacking the air of life and activity which in the past has been characteristic of the town, and to anyone unfamiliar with the substantial character of the resources of the district it might easily appear that Dawson is on the decline. [40] Both the News and the Nugget agreed that the recession was temporary and induced by the restrictive measures imposed by the government. The Election of 1902 The federal election of 1902, the second held in the Yukon for the parliamentary seat, featured the resignation of the commissioner, John Hamilton Ross, in order to run, and his subsequent victory at the polls. Both the Nugget and the Sun supported Ross on the basis that one who had served as chief executive best knew the needs of the territory. To this the Nugget rashly added, in the heat of the campaign (8 November 1902), that Ross was en route to Ottawa there to be sworn in as Sifton's successor. This, averred the Nugget, made their candidate's victory a virtual certainty; certainly with such a man as minister of the interior, the Klondike's troubles would soon be over. The Sun supported the rumour, or ruse, which in any case was to backfire when no such appointment was forthcoming and the unfortunate Ross was for a period too ill to carry out the simple duties of member. Much to the scorn and obloquy of its rivals, the News supported Joseph A. Clarke despite his tarnished reputation and predilection for cheap demagoguery. The News opened its campaign on 23 August 1902 with a wholesale denunciation of the government of the Yukon to date. "If the history of the administration of the Yukon could be written it would stand forever as an example of incapacity, inefficiency and dishonesty." [41] Whether a stronger opposition candidate could have been found than Clarke is debatable; the News backed him as the champion of the miners' rights against the concessionaires and represented itself, as always, as the champion of the people against bureaucracy and privilege. Each paper accused the others of base motives; the News ridiculed the Sun for referring to a man who had been only a year in the territory as "the darling of the people." In November, during the mounting climax in the closing phases of the campaign, the News and Nugget disputed Ross's health and whereabouts. On 11 November the News asserted that the previous evening it had received word from the Toronto Mail and Empire that there was no truth whatever in the rumour that Ross was to be taken into the cabinet. In the same issue the News printed a telegram received from the Los Angeles Times stating that Ross had been confined to the Hospital of the Good Samaritan for three weeks with rheumatism. With all due sympathy to Ross in his affliction, a stern sense of duty compelled the News to reveal the truth to the people. The following day the Nugget contradicted the News, stating that Ross had fully recovered and was about to leave Los Angeles for Vancouver or Victoria momentarily. On 13 November the Nugget printed a telegram under Ross's signature from Los Angeles stating that he had not had a day's illness since leaving Whitehorse and that the report was a cruel rumour devised by his political foes. The News thereupon accused the Nugget of having printed a bogus telegram dated 12 November, signed Hospital of the Good Shepherd, Los Angeles; the News's contention was that there was no such hospital in Los Angeles, proof of the fictitious character of the Nugget telegram. On 15 November the Sun came to the aid of the Nugget, printing a telegram purportedly from Ross, in which the convalescent referred to the Hospital of the Good Shepherd, whereupon the Sun in righteous indignation delineated upon "the dastardly attack on Mr. Ross, the most infamous the Sun has ever known . . . . A more cruel and cold-blooded attempt at political assassination has never been made in Canada." [42] The alleged telegrams agreed on one point — the identity of the patient and the locality, but as to whether in the Good Shepherd or the Good Samaritan infirmary remains a mystery to this writer. It is plain that one or other of the papers was lying. The News story gains a little more credence by inference inasmuch as Ross's health was so poor after his election that he was forced to neglect his duties in the House. The News accepted Ross's victory (by about 900 votes) with good grace, attributing it to the force of his personality. The "creek vote" came as a surprise to the News, which had always championed the miner, but no doubt the miners believed that Ross could secure them the reforms they needed more effectively than his opponent. The News could not forbear a sharp crack at the Nugget. "As everybody knows filthy lucre is the pivot upon which everything turns with the Nugget, and when that is arranged the inexplicable jumble of truncated sentences fellows in nauseating succession." [43] A letter from Congdon printed in the Sun on 6 December deprecated that paper's description of the election result as a Liberal victory; on the contrary, wrote Congdon, it should be considered a victory for the better man, in which Conservatives had thrown party loyalties aside to vote for Ross. The year 1902 closed with a Sun challenge to its two competitors; in its Christmas Day issue, the Sun offered to pay a forfeit of $100 to the town's hospitals if its claim to a November circulation of 33,545 copies could be bettered by either of its contemporaries. The News does not appear to have replied. The Dawson Free Lance In the increasingly competitive world of journalism in the early years of this century, many ventures fell by the wayside. Such a one was the Dawson Free Lance, a Saturday weekly, whose manger and editor was E.J. ("Stroller") White, mentioned earlier in connection with his several columns of chit-chat in the Nugget. Described as the "family paper of the Yukon," the four-page, six-column weekly devoted itself to local news. The reader might well doubt that the little sheet was to be a family paper on reading its first issue of 22 January 1903. On the front page, under the heading "Inch Rope Reminiscences," the editor defended capital punishment and reminisced fondly on a long series of lynchings in the United States. Clearly the "Stroller" held that, in the absence of a legal execution, a lynching was an acceptable and salutary alternative. In the same issue, White commended his sheet to the residents of Dawson and the denizens of the creeks: "A daily paper is fresh for one day only, while a weekly paper is read for a week. The Free Lance contains spice enough to relieve the monotony of life and enough common sense to commend it to all sensible people." [44] On the editorial page of the first issue appears this homely directive reflecting the rough and ready conditions of the Klondike: "Any subscriber paying in cord wood will please bring it free from knots in order that a woman may be able to split it." [45] For all its drolleries and appeals to family sentiment, the Free Lance lasted for only a season. The 1902 Election Aftermath The backwash from the 1902 federal election rolled well into 1903, with the News roasting its two contemporaries on the Ross issue: that he was to be taken into the cabinet and that his health was sound. On 22 June the News called for the member's resignation on the grounds that his health had been so poor that he could not attend to his duties in the House and he had accomplished nothing since going to Ottawa. It was a grave mistake to send Mr. Ross to Ottawa. The News contended throughout the election that his return would be regarded as an endorsement of Sifton, and that the poor health enjoyed by Mr. Ross would militate against his usefulness . . . . Yukoners are accused in the house of endorsing the government and finding fault at the same time. Mr. Ross neglects his duties because he is said to be too sick to attend the session. [46] By this date the Nugget too was reviewing its espousal of Ross's interest. On 1 July 1903 the Nugget owned itself disappointed in the member's poor performance. The Nugget had supported Ross because he gave assurance of being the better candidate, but the paper had not undertaken to endorse a repudiation of campaign promises. The Sun attacked the Nugget for its abandonment of Ross. It was well known that Ross was not well at the time of the election, but his supporters had confidence nonetheless that he would accomplish more for the territory than his opponent. This had been borne out, continued the Sun: reduction of miners' licence fees and appointment of a commission to investigate concessions, maintaining the import of mining machinery duty free, and a liberal appropriation in the budget for Yukon development. At least the News had been consistent in its opposition to Ross, but the Nugget was changing sides. [47]

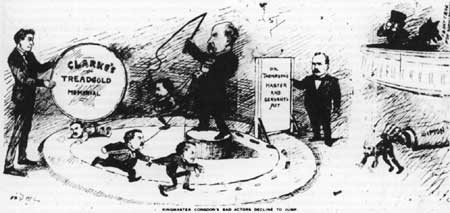

Concessions and Press Rivalry The News renewed its stand on the issue of the Treadgold concession in a leader of 28 April 1903 in which it claimed to have been the only one of the three papers to have opposed the enterprise from the outset. Early in May the News editor clarified the paper's stand on the issue: the principle of hydraulic concessions was not wrong per se, but should only be resorted to when the ground no longer offered a return for placer mining. Obviously the Klondike had not yet reached that stage and yet large tracts were reserved in idleness for future development by concessionaires. This was strangling the economy of the district and it was this to which the News was so adamantly opposed. Sifton was responsible and with his resignation, the News could only rejoice, but the damage was done. On 22 July the editor gave vent to his sentiments regarding the maladministration of the territory. The fact that Clifford Sifton will no longer be empowered to administer the affairs of the Yukon is a source of much congratulation, but "the evil that men do lives after them." The evil that Mr. Sifton has done in this country will be permanent, and the present condition of its mining industry, and commercial paralysis are monumental evidence to his narrow-minded views and limited administrative capacity. [48] On 14 August 1903 the News announced in banner headlines that the royal commission appointed to investigate the concession issue had arrived in the persons of Byron Britton, K.C., and Benjamin T.E. Bell, an engineer. The latter warned, on the day of his arrival in Dawson: The people must come to realize that mining is not a gamble, but a business. It must be conducted along the lines of the utmost careful management and strictest economy. The people of the Yukon will do well to awaken to this fact. [49] On 26 August a mass meeting held in the Auditorium Theatre passed a resolution condemning the Sun for its equivocal policy in the government interest and paying but lip service to the interests of the miners. Then on 8 September the commissioners arbitrarily closed the hearings in the course of a sharp exchange of words between councilman Clarke and Judge Britton. The News saw nothing to be gained from the inquiry and charged Britton with being partisan. Predictably the Britton report defended concessions, but this did not affect the outcome for by June of the following year the remedy had been applied by order in council. Undoubtedly the News displayed a more mature and broader outlook than the other two Dawson papers; its editorials are proof of this. Still, by current standards, its ready acceptance of violence in human affairs and its nationalistic and jingoistic sentiments seem archaic. Consider the News's attitude to boxing, street brawls and war. On 22 February 1904 the News took up the defence of prize fighting against the strictures of the Dominion Ministerial Association which had attacked the sport as brutal and degrading. The News contended that war and prize fighting were close to the heart of Anglo-Saxons; this might be decried, but was fact. Therefore a newspaper must feature these items in order to sell copies. On the whole, continued the editor, this fascination with the prize ring was a good thing for prize fighting and the spirit it engendered were closely associated with war. It would be a sorry day when the great Anglo-Saxon race lost its martial ardour. In its 26 March 1904 issue the News devoted fully half its front page to the Britt-Corbett fight, but felt it necessary to defend a sport as yet assailed by few. In an editorial in the same edition the editor branded opponents of the prize ring as weaklings and cowards; every Briton and American worthy the name loved prize fights and only the hypocritical denied it. A description of a one-sided street brawl reported in the 2 September 1903 edition of the News further illustrates the point. Robert Anderson, a concessionaire (and this factor may have coloured the account), and George T. Coffey, manager of the Anglo-Klondike Company, had been testifying before the two-man royal commission previously referred to, in the course of which Anderson had made some belittling remarks about Coffey. On leaving the hearings, Coffey attacked Anderson, driving him off the sidewalk into the gutter, thence across and down the muddy street, raining blows on him at will, while a crowd looked gleefully on. Poor Anderson, totally outclassed by his agile opponent, cried for help as he back-pedalled his way down the street, finally making a pitiful attempt to arm himself with a stick. With relish, the News continues, When they reached the gutter on the other side of the street Anderson went down and fell in the mud. He seized a stick which was imbedded in the earth, probably intending to use it as a club but Coffey came down on top of him and the fight continued until a couple of policemen arrived and pulled Coffey off the concessionaire. Anderson's face after the fight looked as if some one had tried to print the map of the Lynn canal on it. [50] Coffey was fined five dollars while the case against his badly mauled victim was dismissed. The News's racism. is apparent in an editorial of 16 November 1903, commenting on President Roosevelt's concern over the foreign influx into the United States. The question which appeals to the observer today is whether a government, the genius of which is Anglo-Saxon, is altogether safe in the hands of Huns and Slavs . . . . The change of racial stock in America is so rapid, many now living will yet be alive when America's Anglo-Saxon ancestry will be but a memory as the Norman conquest is but a memory in England today. [51] The News on Higher Education On the subject of university education the News displayed an almost rustic pragmatism, very dated today when so much is made of university degrees of whatever sort and wherever obtained. Schools of journalism may well have been in their infancy in 1903; in any case, they had yet to gain the respect of the News. The contempt the News editor affected for higher education runs through the editorial. The art was "not to be bestowed by a gowned professor, nor to be acquired in the lecture room." [52] The News may well have had a point in its commentary on the plight of graduates with general degrees in the humanities who were thereby fitted for no specific profession or calling. Citing an example of a young man of his acquaintance who had an expensive education, the editor observed, The man's education had fitted him for nothing and had unfitted him for everything, and the alleged mental training he had received at great cost to his parents finally left him stranded in a restaurant as a waiter — and a very poor one at that. [53] In taking issue with a Harvard professor who had ventured the opinion that culture, not earning power, should be the prime goal of the university, the editor of the News gave himself over to a spate of philistine abuse of a liberal education all too typical of a frontier society. For coarse pragmatism and cheap eloquence, the following passage from the editorial columns of the News of 7 January 1904 is hard to equal, let alone surpass. To an observer at a distance the equipment of the college graduate would appear to be less literature than that possessed by an ordinary library attendant; less Greek than was known by the bathhouse attendants of ancient Greece; less Latin than was spoken by Caesar's cook; less practical mathematics than is known by a bank employee at $25 a week; less art than is in the possession of many art studio scrub attendants; less baseball than the ordinary professional graduated from the highways and byways; less watercraft and oarmanship than an ignorant fisherman out of St. John's; less theology than a Salvation Army convert; less powerful oratory than a sandlot demagogue; less practical knowledge of the world as it is than the bootblacks and newsboys on the streets. This is about the equipment of the ordinary collegeman as seen in the Klondike. [54] This was probably the work of W.A. Beddoe, an Englishman who at that time was a News editor, a man for whom Woodside had so little respect that he consistently cut him dead in the street. In writing to Steele in September 1910, Woodside referred to Beddoe as a "spy, blackmailer, turncoat, blowhard, and a liar." [55] Whatever Beddoe was, he was not a man of letters. The News maintained that the hallmark of a good editor lay in accurately gauging public opinion and catering to popular taste. If the above editorial reflects in any way the mentality of Dawsonites in 1903, then (economic factors aside) Dawson was well along the road from mining camp to tank town. The Sun took a middle-of-the-road approach to the value of higher education, but the attitude of both was stricly utilitarian. The Demise of the Nugget Early in 1903 the Nugget renewed its charges of a News-Sun combine directed against the Nugget in a bid by the News to gain a newspaper monopoly in Dawson. In a defensive mood the Nugget announced on 29 January a lowering of its subscription rate to stimulate circulation. Early in February the Nugget repeated its allegations against the News, stating that the latter's policy was not in the public interest. By this time Nugget news coverage was declining noticeably, indicative of the paper's languishing state. On 29 January 1903 the Sun announced a reduction in its subscription rate to $1.98 per month, undercutting the Nugget by two cents. On 4 April the Sun proclaimed that its Sunday edition would total 16 pages by May and that it was the only Dawson paper with an Ottawa correspondent. A four-page colour art supplement was to be added to the Sunday Sun. On 4 June the Sun announced the shipment of two Mergenthaler typesetting machines to replace its present monoline equipment. Coloured supplements and halftone illustrations were in the offing. On 1 July 1903 the Nugget made a special subscription offer in conjunction with the Toronto Globe. Arrangements had been made to include a six-month subscription of the Weekly Globe with an equivalent number of issues of the Nugget for only $12. This is a curious development in view of the fact that on 11 July 1903 George M. Allen informed his readers that both the Daily Klondike Nugget and the Semi-Weekly Nugget, together with plant, stock and fixtures, had been sold to the Record Publishing Company. The last issue of the Nugget, dated 14 July 1903, contained nothing in its six pages to intimate that the paper had appeared on the streets of Dawson for the last time. The two editorials in the final edition dealt with Alaskan self-government and the abuse of parliamentary privilege. There was neither farewell nor valedictory. The News bade farewell to the Nugget in a leader on 15 July 1903. While acknowledging their differences, the News paid tribute to its rival's spirit: the Nugget had never avoided a fight. Allen, a formidable editorial opponent, had yet been a personal friend "outside the editorial sanctum." Whatever the future may have in store for him he will leave Dawson with the assurance that among the friendships that will be cherished he must number among the most sincere, that of his friend, the enemy, and none wish him greater success in the sphere of usefulness in which he may find himself than the News and its staff. [56] The Sun was more frank on its relations with the Nugget. The Sun and the Nugget have had lots of trouble between themselves — hard, bitter, stern troubles — but between ourselves, gentle reader, most of that trouble never happened. Apparently we were the most bitter of enemies, at daggers drawn all the time, but (on the side) that never prevented our borrowing paper and ink of each other whenever the necessity arose — we never borrowed money of each other, because neither has ever had any more money than was needed to keep going. [57] How seriously, one wonders, should editorial warfare be taken? Was much of the journalistic rodomontade written with tongue in cheek? Certainly to all intents the rival papers had gone at it hammer and tongs. Bankrupt on leaving Dawson, Allen returned to the United States where he continued in the precarious trade of catering to the public opinion. With the Sun's absorption of the Dawson Record on 1 November 1903, the government organ and the News had the Dawson newspaper field to themselves. The Record, edited by L.C. Branson and managed by V.H. Smith, had been a short-lived sheet, its first edition dating from 16 July of the previous summer. The six-page, six-column daily had been a morning paper catering to the creeks and was strictly a news sheet with no special features. Its editorial policy had been similar to that of the News: concessions were anathema and the woes of the territory were directly attributable to Sifton, but it was less implacably critical than the News. The Record had adhered to the basic Liberal principle that the Canadian economy was closely tied in with the American and in view of the discrepancies between the two countries in terms of power and wealth, Canada should govern itself accordingly. On Branson's retirement, the Sun at once took over the Record. The Sun had not long swallowed its short-lived contemporary when misfortune struck in a form all too common in the days of early Dawson. Shortly before four o'clock on the afternoon of 19 November a tin of benzine exploded in the Sun's basement. Fire partially destroyed the printing plant, covered by only $5,000 worth of insurance. [58] The Sun thereupon moved in with the News, which placed stock and plant at its unfortunate neighbour's disposal. By 9 December the Sun had returned to its own premises: enough of the plant had been salvaged to continue publication. Before taking leave of its host, the Sun acknowledged the timely and generous help received. We are deeply grateful to the Dawson Daily News management and force for kindness shown us since the fire. All the News has in the way of equipment and paper stock (and it has about all there is in the Yukon) has been at our disposal without money and without price. [59] The News and the Congdon Machine Early in 1904 Commissioner Congdon began to move to ensure his tighter control of the Yukon's political destiny and as one means of doing so he was instrumental in establishing another newspaper. Congdon decided that the Sun was too blunt an instrument to use to influence the voters even though the Sun, barring the Treadgold issue, had supported the government faithfully. Congdon instructed his henchman, William. A. Temple, a sometime railroader supposedly in charge of diamond-drill operations, to establish a new government organ and to secure the services of Beddoe of the News as editor. This Temple did and the result was the appearance of the Yukon World, published daily except Monday, a four-page, seven-column paper selling for 25 cents per copy or two dollars per month. It carried the twin slogans at its masthead: "Reliable and Newsy," "Aggressive, Courteous." Although the World soon demonstrated its aggressiveness, courtesy was foreign to its editorial columns. In the first issue, 29 February 1904, the editor stated the paper's policy. Today the Yukon World enters the field of Dawson journalism. In politics the World will be Liberal, supporting the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, but with a Yukon policy well defined and quite obvious. The World has an abiding faith in Yukon and its future, and also entertains the view that the government has done much and may be confidently expected to do more to encourage those who have made this remote portion of the Dominion famous. [60] The World commented that the Sun has had no comprehension of the importance of the functions it was expected to perform, and as a newspaper it may properly be described as a failure. The World entered the field because the field was not covered, that was not our fault, but our opportunity. [61] The News reacted coolly: "Papers may come and papers may go, but the News goes on forever." [62]

The Sun fought back, still maintaining its position as the government organ and mouthpiece of the Liberal party in the Yukon and asking how the World could claim such a role while employing as editor one who had served the principal opposition paper for years? Although the World relegated the Sun to spokesman of a mere splinter group within the Liberal party, the Sun insisted that there was no split in the party and that it still was the one Liberal paper in Dawson. This was little more than bravado, however, for by the end of March it had been announced officially that after 2 April 1904 the Sun would no longer contain the Yukon official gazette. [63] The Sun had been deprived by the commissioner of government patronage, so long a source of contention in the Dawson journalistic world, in line with his policy to replace it with a paper more to his liking. It is surely no coincidence that on this same date, the Sun denounced Congdon for ignoring his splendid opportunity to redress long-standing grievances on becoming the chief executive of the territory and instead choosing to surround himself with time-servers and party hacks in his endeavour to dominate the territory in his own interest. It is only right to state the Sun is distinctly and mightily embarrassed over having to come to this point. The Sun stands for the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal party, believes in it and can conscientiously preach to all . . . . That Commissioner Congdon will be replaced, and soon, is as certain as that the Liberal government of Canada is right . . . . Commissioner Congdon, W.A. Beddoe and the commissioner's select coterie of paid supporters must travel together in future to the end, for the Sun must stay with the Liberal party which they are attempting to disrupt. [64] In effect, the faithful Sun was forced into opposition. |

|||||||||||

|

||||||||