|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 13

Table Glass Excavated at Beaubassin, Nova Scotia

by Jane E. Harris

Late 18th-Century English or American Glassware

Most of the glass artifacts from Beaubassin were of English

manufacture. A few were of suspected American manufacture, but all were

made after the middle of the 18th century. The variety of types —

wine bottles, case bottles, snuff bottles, medicinals and lead glass

tableware —seems to indicate an almost continuous occupation of the

site after the expulsion of the Acadians up to the early 1800s.

Cylindrical Wine Bottles, ca. 1750-1770

Throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries, wine was commonly

bought and stored in wooden barrels, and wine bottles, such as the

globular bottles discussed earlier, were merely used for serving in

taverns and at the table (Price 1908: 116; Leeds 1914: 290). In the

first half of the 18th century it became a custom to bin wine in bottles

at first upside down and then on their sides (McKearin 1971:125, 127),

thus necessitating a change in bottle shape, for bottles with bulbous

bodies were inconvenient storage vessels for these methods. The sides of

the body then became straighter, and by about 1750, wine bottles

commonly had short, cylindrical bodies with broad bases. Their necks

were still tapered but had a slightly more complicated finish than

previously. The lip was everted over a down-tooled string rim, a style

consistent throughout this period which NoŽl Hume dates as about 1750 to

1770 (NoŽl Hume 1961: 104). Between 12 and 20 bottles of this type were

represented by 22 fragments varying in colour from 10Y to 5Y.

Figure 3 illustrates a typical neck and base of this style of bottle.

The neck (Fig. 3, a) is olive green (7.5Y), vertically striated

and lightly seed-bubbled. It is short and tapered, finished with an

everted lip and down-tooled string rim. Its dimensions are included in

Table 1 with the dimensions of six other finishes of this form and

period from Beaubassin. The base (Fig. 3, b) is of heavy, seed

bubbled, olive green (7.5Y) glass. Its base is broad, 119 mm. in

diameter, and has a distinct basal sag. The push-up is bell shaped, 37

mm. high, and bears two marks, one of which is a pontil mark 59 mm. in

diameter. The other mark is a shallow quatrefoil impression, 40 mm. in

diameter, formed by pushing the base up with a quatre foil-tipped rod

(Jones 1971: 66). The pontil mark was left by a sand pontil which

somewhat diffused the first mark as the sand-covered glass of the pontil

followed the contour of the basal surface (Jones 1971: 69).

Table 1. Cylindrical Wine Bottle Necks

|

| Dimensions (in mm.)

|

Specimen

No. | Lip

diam. |

Lip

Ht. | Str.

Rim

diam. |

Str.

Rim

ht. | Finish

ht. |

Neck

ht. | Neck

diam. |

|

| 7B2D1-1 | 28 | 4 | 34 | 7 | 11 | 82 | 25,32,48 |

|

| 7B102-7 |

| 50 |

|

| 7B1C2-15 | 27 | 3 | 34 | 6 | 9 |

| 25 |

|

| 7B1D2-1 | 27 | 4 | 32 | 5 | 9 |

| 25 |

|

| 7B203-2 |

| 33 |

|

| 7B3E3-1 |

| 4 |

| 5 | 9 | 80 | 34,51 |

|

| 7B3B1-19 |

| 33,50 |

|

3 English wine bottle fragments, ca. 1750-70: a, bottle neck

(7B2D1-1); b, bottle base (782A2-2).

|

Of the remaining fragments there were seven bases large enough to be

positively included in this group, along with several smaller fragments

which satisfied most of the conditions of description such as basal

shape and diameter, empontiling technique and colour. Their approximate

diameters ranged from 110 mm. to 130 mm. with a mean of 116.8 mm.

Cylindrical Wine Bottles, ca. 1770-1800

In the years between 1770 and 1800, wine bottles changed considerably

into what NoŽl Hume (1961: 105) calls the "evolved cylindrical form."

The body was now tall and slender with a much smaller basal diameter

than before. The neck had become longer and more cylindrical and was

often bulged in the middle. Additional glass was sometimes used to form

the lip and the string rim, making finishes generally larger and more

varied in shape.

The specimen shown in Figure 4 is a good example of this form. It is

a tall (265 mm.) cylindrical bottle of seed-bubbled, olive green (10Y)

glass with an iridescent patina. It has a sand pontil mark close to the

edge of the base and a flat, circular impression at the tip of the

push-up. A description of this bottle is given in Table 2. There were

only about a dozen bottles of this type, represented by 12 fragments.

The two neck fragments illustrated in Figure 5 possibly belong to the

early part of the time period (1770-1800), whereas the bottle in Figure

4 with its more advanced finish could be closer to the end of the

period. The specimen shown in Figure 5, b is a very ordinary,

almost cylindrical neck with an everted lip and downtooled string rim.

Figure 5, a varies slightly in having a less common uptooled

string rim; however, a finish of this form was found at Rosewell,

Virginia, in a post-1770 archaeological context (NoŽl Hume 1962: 215).

Neck dimensions can be found in Table 3.

4 English wine bottle, ca. 1770-1800 (7B1C5-2).

|

|

| Table 2. Description of Cylindrical Bottle (Fig. 4) |

|

| Dimensions (in mm.)

|

| Body part | Shape | Height | Diameter(s) |

|

| Lip | Downtooled | 9 | 37 |

|

| String rim | Downtooled | 6 | 34 |

|

| Neck | Roughly cylindrical | 90 | 27,37,44 |

|

| Body | Cylindrical | 150 | 94,91,88 |

|

| Base | Basal sag |

| 94 |

|

| Push-up | Rounded | 33 |

|

|

5 English wine bottle fragments, ca. 1770-1800: a, bottle neck

(7B2C3-4): b, bottle neck (7B2C1-2); c, bottle base

(7B1C2-11).

|

Table 3. Cylindrical Wine Bottle Necks

|

| Dimensions (in mm.)

|

Specimen No.

and

Colour | Lip

diam. |

Lip

Ht. | Str.

Rim

diam. |

Str.

Rim

ht. | Finish

ht. |

Neck

ht. | Neck

diam. |

|

7B2C1-2

10Y | 31 | 4 | 35 | 6 | 10 | 94 | 27,35,46 |

|

7B3C3-4

10Y | 31 | 4 | 34 | 11 | 15 | 65+ | 26,30 |

|

7B3A3-2

7. 5Y | 27 | 4 | 32 | 5 | 9 | 67+ | 26,35 |

|

The base illustrated in Figure 5, c is almost identical to

that of Figure 4, save for a slightly larger diameter, 102 mm. The same

empontiling technique has been used and the base has been pushed up in

the same manner. In this case the sand pontil mark is 60 mm. in diameter

and the circular impression at the tip is 24 mm. in diameter. The

push-up has a rounded profile and is 33 mm. high. The glass is olive

green (10Y), slightly patinated and heavily seed-bubbled.

The remaining specimens are mainly base fragments with rounded basal

profiles. Their colour, olive green, varies from 10Y to 7.5Y, one

fragment being 5Y. Approximate base diameters range from 95 mm. to 105

mm. on six base fragments measured.

Case Bottles

Square-sectioned bottles blown in dip moulds were being manufactured

as early as the first half of the 17th century in England, and

apparently preceded circular bottles as containers for wine (NoŽl Hume

1969a: 33). Their popularity decreased in the latter half of the 17th

century with the manufacture of stronger circular bottles, but increased

again greatly in the 18th century when they became containers for a

variety of substances such as medicines, blacking and gin.

Case bottles from the 18th and early 19th centuries can be

distinguished by their bodies which taper from shoulder to base, their

horizontal shoulders and very short necks. Finishes were rudimentary,

consisting only of an applied lip or collar. Most often the bases were

concave resulting in a four-point bearing surface. Frequently the basal

surface was marked with simple embossed designs. The style remained the

same until the early 1800s when the use of hinged moulds increased

(Toulouse 1969b: 535). There were at least six case bottles represented

by the 33 fragments.

The specimen illustrated in Figure 6, a is a very typical case

bottle base. It has a four-point concave bearing surface which has a

ring-shaped pontil mark at the centre. Corners of the body are very

sharp, and distinct withdrawing lines can be seen on the body. The

dimensions of this base and the other measureable case bottle base

fragments from be found in Table 4.

|

| Table 4. Case Bottle Bases |

|

| Dimensions (in mm.)

|

Specimen No.

and Colour | Base | Push-up

ht. | Pontil

diam. |

|

7B3B1-11

2.5GY | 69+ | 10+ |

|

|

7B193-7

10Y | 86+ | 10+ | 11,23. |

|

7B192-2

10Y | 91 x 92 | 6 | 55 |

|

7B1C2-2

7.5Y | 8 4x 85 | 1B | 14,24 |

|

6 Case bottle bases: a, base with ring-shaped pontil mark, 18th

century (7B1C2-2); b, base with sand pontil mark, 16th century

(7B1B2-1).

|

Beaubassin can

The second specimen in Table 4 is identical to the base in Figure 6,

a with one exception. Embossed on the basal surface and partially

obscured by the pontil mark is a simple Greek cross, a common mark found

on case bottle bases.

Another specimen differs from the other case bottle bases in having a

large sand pontil mark on an almost flat base (Fig. 6, b). The corners

of the body are rounded, possibly due to the thicker glass used.

Of the remaining case bottle fragments, that shown in Figure 7, a is

a typical neck and shoulder. The shoulder is horizontal and joins a

short neck with an applied trumpet-shaped lip. Including the lip, the

neck is only 30 mm. high. The lip itself is uneven, varying from 8 mm.

to 11 mm. in height, and has a diameter of 39 mm. The neck tapers under

the lip, its diameter ranging from 24 mm. to 34 mm. at its base. The

shoulder is approximately 80 mm. square.

7 a, case bottle neck and shoulder fragment, 18th century

(7B3A1-3); b, snuff bottle neck, 18th century (7B2A1-1).

|

The remaining fragments are flat-sided body fragments, some with

part of a 90-degree corner extant. They range in colour from 5GY to

7.5Y. Bubbling varies from light to heavy.

Square-sectioned bottles such as the case bottles just described did

not always have narrow necks. Some were for substances such as snuff,

jalap or pickles, in which case a wide mouth would be necessary. Wide

mouthed bottles are illustrated in McKearin and McKearin (1948: Pl.

227), Watkins (1968: 151) and Munsey (1970: 86). Most of them have

straight sides and almost flat bases similar to 17th-century case

bottles (NoŽl Hume 1969a: 34).

Snuff Bottles

The practice of taking snuff in England and America extended from the

18th century until well into the 20th century. Containers for snuff were

varied, bottles being used mainly for selling snuff and not for storing

it in the home (Munsey 1970: 77).

Snuff bottles were either mouth-blown into an octagonal or

square-sectioned dip mould, or blown and then "paddled" (Munsey 1970:

77) into shape, presumably by means of a wooden paddle used to flatten

the sides. They had a wide mouth with a short, rudimentary neck.

Finishes were not limited to any particular form. The lip, often

everted, could also be plain, downtooled or rounded. String rims, when

present, were often downtooled. The base was usually almost flat and

generally bore a sand pontil mark. The snuff bottle shape changed little

through the 18th and 19th centuries; however, bottles manufactured after

the 1860s can be distinguished by the absence of a pontil mark. It was

at this time that the snap case was developed (Scoville 1948: 17;

Toulouse 1969a: 532).

At least four snuff bottles were found at Beaubassin, represented by

14 fragments. One specimen (Fig. 7, b) is a typical snuff bottle

neck and finish of olive green (2.5GY), seed-bubbled glass. Its lip has

been sheared or cracked off and then everted. It is 49 mm. in diameter

and 6 mm. high. The applied string rim is approximately 5 mm. high. 50

mm. in diameter and roughly downtooled. Below the string rim the neck,

with a slightly concave profile, is 40 mm. in diameter and only 22 mm.

high.

Two snuff bottle bases in the collection are both octagonal, though

only one is measureable. Its base is 60 mm. wide and approximately 85

mm. long. The basal surface has been empontiled in some manner, leaving

an irregular pattern of chips of glass on the surface. It is difficult

to determine whether the bottle was paddled or blown-moulded.

The remaining fragments are base, body or shoulder fragments. Those

from the base and body have corners greater than 90 degrees and colours

ranging from 2.5GY to 7.5Y. Most of the fragments have a pitted outer

surface texture while a few are smooth and glossy.

Medicine Bottles

There were two different types of medicine bottles found at

Beaubassin: a patent medicine bottle and a cylindrical green phial.

A patent for medicine was first issued in England in 1711

(Griffenhagen and Young 1959:159). In 1744 Robert Turlington patented

his well-known cure-all, "Balsam of Life." In an effort to protect their

medicines from fraudulent imitations, patentees used specific bottles

made especially for them. In 1754 Turlington issued a broadside showing

the latest and final form of the Balsam of Life bottle. It was a small,

flat, pear-shaped bottle with chamfered corners and embossed lettering

on all four sides. Judging from the large number of variations of the

original bottle found. it would seem that Turlington's attempts to

thwart imitators were only moderately successful.

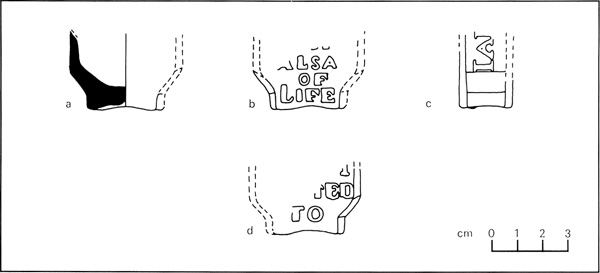

8 Turlligton Balsam of Life bottle, ca. 1754-1660: a, profile of

base; b, front panel of body; c, side panel; d,

back panel (781C5-1).

|

A fragment of a clear lead glass Turlington's Balsam of Life bottle

was found at Beaubassin. The lower part of the body is present to a

height of 29 mm., close to half of its complete height. It widens above

the base and has chamfered corners. The widest part of the body is 44

mm. wide and 22 mm. deep. It has a slightly pushed up (3 mm.) and pitted

basal surface 22 mm. wide and 30 mm. long, diagonally bisected by a

thick mould line. There is evidence of empontiling. The embossed

lettering, according to the broadside issued in 1754, is as follows with

the letters present on the Beaubassin specimen italicized: BY THE

KINGS ROYAL PATENT GRANTED TO / ROBT TURLINGTON FOR HIS INVENTED BALSAM

OF LIFE / JANUY 26 1754 / LONDON. The bottle from Beaubassin is

probably an original Turlington bottle, and since it is made of lead

glass it was most likely manufactured in England. According to Munsey

(1970: 65), embossed bottles were not common in the United States until

after 1810 and then they were probably made of non-lead glass. The

lettering and body shape, as much as is extant, are like those of the

broadside. The bottle probably arrived at Beaubassin with the British

who came to the area in the 1750s, but could, although it is not likely,

date as late as the 1850s or 1860s as it is empontiled. Turlington's

Balsam of Life was used up to the early 1900s; bottles were still being

advertised in the Illinois Glass Company catalogue of 1903.

The second medicine bottle type, a phial, is represented by a base

and a body fragment, both of green (2.5G) glass, and possibly from the

same bottle. The base (Fig. 9, a) has a high conical push-up with

a sheet of glass, the pontil mark, almost completely covering the

opening; thus measurement of the push-up height is difficult but it is

approximately 30 mm. high. Basal diameter and pontil mark diameter are

40 mm. and 23 mm. respectively. The body fragment is circular in

cross-section.

9 a, English phial push-up, pre-1750 (781H1-1); b, clear

lead glass bottle of uncertain use, early 1800s (7B1E7-5).

|

Phials were common during the first half of the 18th century (NoŽl

Hume 1969a: 42-3) but seem to have been gradually replaced by clear,

lead-glass bottles sometime after 1750. Medicine bottles of this type

had cylindrical or slightly steeple-shaped bodies with short necks and

flanged lips.

Unidentified Bottles

Five vessels were found at Beaubassin which were difficult to

identify positively. One of these is a small clear glass bottle, 46 mm.

in diameter at the base and present to a height of 25 mm. It is made of

poor quality but shiny lead glass, full of seed bubbles and non-glass

inclusions. The body has been mouthblown into a plain, vertically ribbed

dip mould, removed and marvered flat, forcing the ribs to appear on the

interior surface of the body. The bottle was then empontiled with a

glass-tipped or ring pontil which left a scar 20 mm. in diameter and a

push-up 7 mm. high. The neck was simply finished by rolling the

cracked-off lip down onto the neck, resulting in a downtooled "collared"

lip approximately 23 mm. in diameter and 6 mm. high. A hypothetical

reconstruction of this bottle appears in Figure 9, b.

Its manufacturing technique and style suggest it may be of early

19th-century midwestern American manufacture (McKearin & McKearin

1950: Pl. 107); however, the possibility of late 18th-century English

manufacture (Davis & Middlemas 1968: 54-55) cannot be overlooked.

Covill (1971: Fig. 224) illustrates a very similar bottle identifying it

as an inkwell.

The second bottle, possibly a pocket flask or perfume bottle, may

also be of early 19th-century, mid-western American manufacture. Only a

small fragment of a cylindrical neck with a slightly rounded, slanting

shoulder remains. The bottle has been mouthblown in a vertically ribbed

dip mould. On the neck the ribs have been flattened, possibly a result

of the tooling involved when shaping the neck.

A third bottle is represented by one base fragment of light green

(7.5GY) glossy glass. The base is either square or rectangular with

chamfered corners, and its complete width is 40 mm. There is a

glass-tipped pontil mark 21 mm. in diameter on the almost flat base. A

mould line diagonally bisects the basal surface. Glass colour and body

shape suggest this may have been a condiment bottle. Since the bottle is

empontiled it was probably manufactured after the late 18th century but

before the 1860s (NoŽl Hume 1970: 75), and could be of either English or

American manufacture,

Two more bottles are represented by fragments. Both are flat-sided

and of unknown origin or function. One specimen of green (10G) glass is

very densely seed-bubbled. One edge of the fragment has the beginning of

a corner. The side has an extant width of 63 mm. The other fragment, of

seed-bubbled, blue-green (5BG) glass, has the beginning of two rounded

corners giving it a side width of approximately 35 mm. There are faint

vertical ribs on the fragment which may or may not have been

deliberate.

Lead Glass Tableware

The lead-glass tableware from Beaubassin consists largely of

plain-stemmed glasses, the common utilitarian ware one would expect to

find on an 18th-century British site. There were plain-stemmed wine

glasses, firing glasses and one decanter stopper. A maximum of 16

objects was found.

Firing Glasses

Firing glasses are short, thick-stemmed glasses with heavy conical or

almost flat feet and usually trumpet-shaped bowls. Primarily of English

manufacture, they were popular in the last half of the 18th century

(Hughes 1956: 229), but were manufactured from about 1730 to well into

the 1800s (Ash 1962:84-6).

Firing glasses are represented by two stem fragments, one foot

fragment and one possible bowl fragment. The stems are 20 mm. in

diameter, the tallest having an extant height of 37 mm. The foot is 11

mm. thick and has an approximate diameter of 65 mm. The bowl fragment is

trumpet-shaped with an approximate lip diameter of 55 mm.

Plain-Stemmed "Wine" Glasses

The remaining plain-stemmed ware fragments are from the more familiar

"wine" glasses. There are at least 7 and possibly 10 glasses represented

by 10 fragments. Even though the sample is rather small, there is a

surprising amount of variety; no two glasses are alike. All of the feet

appear to be of a plain conical form, but one has the added feature of a

folded foot rim. Folded foot rims were common before 1745 (Elville 1951:

88; Thorpe 1969: 209) and again popular after about 1780 (Elville 1951:

89). This foot could easily belong to either period.

Two stems have air tears at the stem base. This is a difficult

decorative technique to date due to the differing views held by several

authors. Hughes (1956: 88) and Elville (1961: 55) maintain that tears in

stems disappeared by 1745-50, possibly due to the increased popularity

of air twist stems about this time, but Haynes (1959: 246) feels they

were more popular after the Excise Acts of 1745-46, and logically so, as

they would make a glass slightly lighter. In any case, tears in the stem

are an indication of 18th-century English manufacture.

Only two bowls were present to any extent. One specimen has a drawn

stem indicative of two-piece manufacture as was most common for

plain-stemmed glasses (Haynes 1959: 246). The other bowl was welded to

its stem indicating three piece manufacture. As a result the base of the

bowl is convex. This bowl seems to be later than the other, possibly

late 18th century (McNally: pers. comm.).

Decanter Stopper

A finial from a clear glass, ball finialled stopper was found at

Beaubassin. The ball is heavy and contains one large air tear. According

to Hughes (1956: 254) finials of this type containing a tear were not

manufactured in England until after 1710, and it seems likely they were

seldom made after mid-century with the changing styles away from heavy,

globular shapes as effected by the Excise Acts of 1745-46 (Thorpe

1969:201).

Similar finials have been found at Fort Beausejour, N.B. (McNally

1971a: 89) and Fort Amherst, P.E.I. (McNally 1971b: 13), although each

has several tears instead of only one. Both of these sites were occupied

by the British after 1755 and 1758 respectively, indicative either of

the repeated use and long life of tableware or a longer period of

popularity for this form than has been assumed. It is possible, of

course, that the finial from Beaubassin was manufactured in the first

half of the 18th century but not deposited until the last half.

|