Volume IV

by W.F. Lothian

Chapter 9

Guardians of the Wild

Introduction

In the preservation and administration of our national park heritage, the Park Warden Service fills an exacting and continuous role. For more than 75 years, these guardians of the wild have functioned as fire rangers, game guardians, fishery inspectors, police officers and members of mountain search and rescue teams. They also have, through long association with park visitors, served with distinction as information and public relations officers. Through changing seasons, in fine weather and foul, they fulfill a most important function in national park administration as conservation officers, counsellors and as friends in times of need.

An 'accident victim' is lowered to safety in a mine rescue basket at a park warden mountain rescue school in Banff National Park.

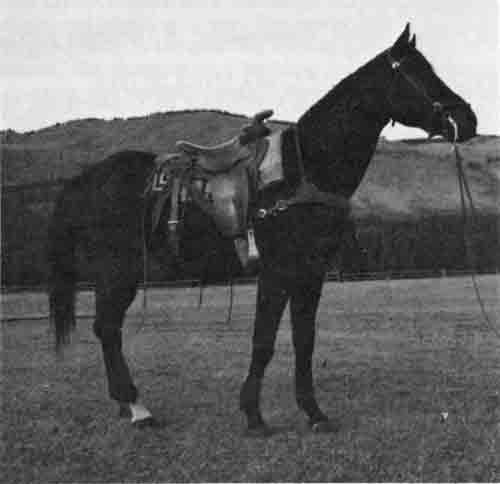

Brun, a registered stallion bred national park saddle horses at the Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch.

Chief Park Warden Howard Sibbald (right) and Park Warden Charles Phillips with new fire truck at Rocky Mountains (Banff) Park in 1915.

First Forest Ranger

The first person delegated to perform the duties of forest ranger in Rocky Mountains (Banff) National Park, following its creation in 1887, was John Connor. In its early days the national park suffered greatly from forest fires, many of which occurred along the right of way of the newly completed Canadian Pacific Railway. Connor's duties consisted mainly of making daily patrols along the railway line in a handcar, and in recruiting fire suppression crews when fire swept down the Bow River valley on the embryo town of Banff. Connor also was called upon by Superintendent Stewart to perform clerical duties as required. The date of Connor's appointment is not known, but he was one of a large group of Banff citizens recommended by the superintendent in 1887 for a lease on a townsite lot. Connor once held leasehold rights to a lot on Banff Avenue now occupied in part by the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Connor died in November 1890, and his widow conveyed her interest in the property to another party. No record of Connor's successor as forest ranger is available from existing departmental files.

Forest and game protection was apparently carried on in a haphazard manner in Banff and other western parks until 1909, when the park warden service was organized. Annual reports of the park superintendents indicate that a fire well under way was very difficult to control, unless providential rains intervened to extinguish it. In May 1903, a fire raged for three days a few miles west of Banff Station. In his annual report for 1906, Superintendent Douglas noted that twice-daily patrols of the railway line had prevented what might have developed into disastrous fires, caused by sparks from passing trains; but it was impossible, he said, to prevent fires from spreading. He recommended a special appropriation to combat, detect and suppress fires, especially if the prevailing dry seasons continued.1 Two years later he again complained about the difficulty in protecting both forests and game, and recommended the appointment of permanent staff whose duties would combine those of both game and fire warden.

Warden Service Organized

Superintendent Douglas's hopes for a protective service were realized in 1909. On June 21, 1909, the National Parks general regulations were revised by order in council, enabling the Minister of the Interior to appoint "game guardians" with authority to enforce the laws and regulations within the parks.2 Each game guardian was given a badge of office, which he was required to display "on every occasion when he is exercising the authority of his office." The new regulations also authorized better control of travel through the parks by visitors and better control of the lighting of open fires; to prevent railway fires, they required that every locomotive passing through a park be equipped with the most improved device to prevent the escape of fire from the smokestack, furnace or ashpan of the engine.

Better game and fire protection also was anticipated by new clauses in the regulations. Besides the rigid protection of all game, these clauses provided for the sealing of firearms carried by visitors through the parks, the control of dogs, the establishment of a season for sport fishing, and the prohibition of illegal fishing practices such as netting or trapping fish or exploding dynamite in park waters.

A forecast of the proposed organization of the warden service was contained in the report of the Commissioner of Parks for the year ending March 31, 1909. It read as follows:

They (the wardens) will patrol all portions of the parks and regular patrol trails, and small cabins will be constructed in different portions of the parks where the men can remain overnight and avoid the necessity of packing tents, etc. with them. Each will be furnished with a saddle pony and a pack pony carrying supplies, so that they can remain out for several days at a time or as long as their patrol duty in any locality may require.

... The instituting of a systematic patrol and the adoption of more stringent fire regulations in respect to the care of camp-fires by tourists should have the effect of greatly reducing the danger from this source and assist us in the effort to preserve the forests of the parks in the state of primeval nature which is one of their chief charms.3

The new warden service for Banff Park, consisting of three permanent officers, was headed by Howard E. Sibbald as chief fire and game warden. Sibbald had rare qualifications, having been raised and educated in the early west. His father, Andrew Sibbald, was a pioneer teacher in the Northwest Territories, who had trekked across the prairie from Winnipeg in 1875 to take charge of the Methodist Mission at Morley, Northwest Territories. Consequently, his son Howard had a background of more than 30 years of living and travelling in the foothill and mountain region of what is now Alberta, assimilating a vast practical knowledge of the area.

In the years following 1909, Sibbald developed, with the encouragement of the Commissioner of Parks, improved practices in game and fire protection, trail construction, forest patrols and other functions of a warden service. Before 1909 a few game guardians and fire rangers had been employed on a seasonal basis, but they were handicapped by a lack of direction and the statutory authority to carry out their duties effectively.

In 1913 Sibbald undertook a forest survey of the Bow River valley within the park. The following year he advocated cutting a fireguard west of the Cave and Basin Springs at Banff as a protective measure against fires. Although this work had been advocated by the Whitcher report of 1886, it was not completed until 1916. A fire lookout was stationed at the weather observatory on Sulphur Mountain, and the telephone line from that point to Banff was reconditioned. Concurrently, in 1914, a start was made in the construction of a field forest telephone system, which eventually provided communication from all warden districts and main patrol cabins to park headquarters. By March, 1915, a 28-mile line had been constructed from Banff to Canmore, and another line 9 miles long was built from the warden's cabin at the eastern end of Lake Minnewanka to its western end. Later, lines were extended to Stoney Creek up the Cascade River, to Healy Creek where it enters Bow River, and to Castle Mountain.

Fire Pump Developed

From five years of practical experience, Sibbald found that the warden service was handicapped for want of modern fire suppression equipment. For years, fires had been fought with green pine tops, wet gunny sacks, axes, shovels, mattocks and water pails. What was required was a mechanical device whereby water could be taken from a natural source of supply to the scene of a fire in sufficient quantities to make the use of such equipment practicable. Commissioner of Parks J.B. Harkin referred the problem to the Board of Railway Commissioners, where it was turned over to Harry C. Johnson, its fire inspector, for a solution.4

Johnson studied various types and arrangements of engines and pumps available. Keeping in mind the vital matters of weight, portability and easy manipulation, he decided upon a marine type of two-cylinder gasoline motor of about six horse-power to supply energy. This was coupled to a special rotary pump, and the assembly, with necessary attachments, was mounted on a single base. After testing, in which many factors were considered, a gasoline portable pumping unit designated No. 1 was built. This combination was found to be capable of pumping 20 gallons of water per minute and lifting water to a height of 172 feet. During a capacity test, water was pumped through 1,500 feet of 1-1/2 inch hose to a height of approximately 85 feet.5 The unit weighed 118 pounds stripped and 143 pounds with an oaken base. Two pumping units could be transported on a single horse, with hose carried by a second animal.

Units of the new pump were tested in two locations in Ottawa, one at the foot of the Rideau Canal locks, and the other in the yards of the Grand Trunk Railway. Tests also were carried out in both Banff and Jasper Parks, as photographs in possession of the National Parks Branch confirm. In field service, it was planned to use pumping units in relays, whereby No. 1 pump would supply water to No. 2 pump, which in turn would supply a third unit, and so on. To permit rapid transport along park roads, a Ford automobile chassis was purchased and equipped with a suitable box body capable of carrying hose and pump units as required. In addition, a specially designed wagon three feet wide and capable of being hauled either by hand or by horse, was built for use on park trails.

In its field tests, the fire engine and pump exceeded expectations. Chief Warden Sibbald reported that "we carried the water in one instance over a steep hill 200 feet high, and along a clearing for 600 feet, the gauge showing a pressure of from 85 to 90 pounds." Park Warden Charles Phillips reported that the whole apparatus was given a very fair four-day test at the Alien Detention Camp near Castle Mountain, where large piles of brush and small timber were burned in perfect safety. During the season of 1915, in which the new equipment was introduced, the park superintendent purchased a motor launch from a Banff boat operator for use by wardens engaged in fire and game patrols on Lake Minnewanka.

Modifications of the original motor-driven fire pump units were made during subsequent years, although the basic design was retained. In his annual report for 1920-21, the Commissioner of Parks reported that the great success which had attended the use of the portable firefighting equipment developed for the Branch suggested the construction of a larger engine to use in combatting fires along motor roads in the parks. Consequently, the branch ordered for use in Banff Park a new 3/4 ton Reo chassis, on which was installed a pumping unit capable of delivering 130 gallons of water per minute at a pressure of 120 pounds per inch. The new fire truck also was equipped with 2,000 feet of 2-1/2 inch linen hose.

The original type of fire pump used by the park warden service of the various parks has long since been supplanted by more advanced types. The newer fire pumps presently in use are of a more compact design, are lighter and thus easier to transport. Consequently they are more adaptable for varying situations which must be met. The 1915 fire pump unit, however, was a great step forward in helping to combat and control an ever-present threat to national parks — forest fires. Its creator, Harry Johnson, lived to witness many changes, for he died at Ottawa in January, 1980 — 99 years old.

Forest Conservation Stressed

With practical fire-fighting equipment now assured, Commissioner Harkin next instituted a campaign of public education about the need to prevent forest fires. As he observed in his annual report for 1915-16: "Practically, there are only two kinds of fires, so far as the parks are concerned: those arising from human causes and those caused by lightning. We cannot prevent fires that are caused by lightning but those of human origin are nearly always the result of carelessness or ignorance. It is simply another case of 'not knowing it was loaded', because the necessity for care is not realized."

The commissioner arranged for the printing of suitable fire-warning notices on articles that were commonly used in the woods, so that a warning should constantly be before park visitors when they were liable to start fires. Two leading Canadian manufacturers of matches agreed to print warnings on practically all the match boxes they sold. Eddy's matches boxes, both large and small, carried the admonition: "Do not throw away burning matches, especially in the woods. Printed at the request of the Dominion Government." Notices were inserted in rifle and shotgun ammunition boxes; labels affixed to axes by Canadian manufacturers called to attention the need for fire prevention in the forest; and a leading tent manufacturer in Ottawa inserted on its trade-name label the words, "Save the Forests. Extinguish your campfire thoroughly." The Bell Telephone Company, the Canadian railway companies, operators of livery rigs and pony concessions, and hotel owners in the parks, also cooperated in conveying the need for care in the use of fire.6

Consequently, the users of park highways and trails were confronted, at suitable places and intervals, with metal or linen signs stressing the need for care in the use of campfires, matches, tobacco products and any other medium that could cause a devastating forest fire.

Park Trails

Many of the earliest walking trails developed in the western national parks were constructed and maintained by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company for the benefit of guests at their mountain park hotels. Glacier House in Glacier Park was closed in 1925 and dismantled four years later, but Canadian Pacific trail maintenance crews continued their operations in the vicinity of Chateau Lake Louise, Lake O'Hara, Emerald Lake Lodge and Yoho Valley Camp until the end of the 1952 season. The maintenance of these trails was then taken over by the park superintendents. Saddle pony trails, however, were the responsibility of the national park administration. They not only permitted visitors to enjoy outings on horseback far beyond the confines of park townsites, but also provided routes for patrols and for the transport of fire-fighting equipment by the park warden service as required. In turn, many of the earlier and more important horse trails were widened and improved to the status of fire roads, capable of accommodating motor vehicles engaged in various phases of park administration.

One of the earliest riding trails developed by the superintendent in Banff Park led from the town of Banff to Lake Louise Station, then known as Laggan. It followed the valley of the Bow River along the north side, and was improved by Superintendent Douglas in 1904-05. After the park warden service was organized, trail development got under way in earnest; and at the end of the 1911 season, the superintendent was able to report that 167 miles of horse trails had been constructed. In 1912, trails were cut from Canmore to White Man Pass, a distance of four miles, at a cost of $100; Brewster Creek trail was extended for 3 miles at a cost of $100; and a trail extension from the logging road up Spray River to Spray Lakes was built for $300. At that figure, it was a bargain for a 12 mile stretch. By April 1, 1914, the number of trails either constructed or improved in Banff Park numbered 60, and entailed 759 miles of construction. The shortest trail listed was one mile; the longest, from Banff to Laggan, was 38 miles.

Similar trail development work was undertaken in other national parks. In 1909, Lake O'Hara, one of the most beautiful lakes in Yoho Park, was made accessible by pack trail from the railway line at Hector. Forest ranger "Kootenai" Brown reported in 1911 that a trail had been constructed from Cameron Falls, in Waterton Lakes Park, southerly along the west side of the upper lake to the international boundary, a distance of 5 miles. Jasper National Park, then the largest in the park system, offered almost unlimited opportunities for trail development, and eventually the length of trails in that park exceeded 580 miles. One of the longest led from Jasper southerly to the summit of Sunwapta Pass, a distance of 70 miles. It joined up at the pass with the trail system in Banff Park to the south, and provided a continuous saddle-pony trip through the mountain ranges from Lake Louise to Jasper, a distance of about 142 miles. The route is now followed, with a few deviations, by the inter-park Icefields Highway. By the end of 1955, the total length of the national park trail system, excluding that of Wood Buffalo Park, was 2,300 miles.

Trail Riding and Hiking

Although the improvement and development of motor roads in the national parks cut heavily into the horse livery business in the mountain parks, riding was given a decided lift when the Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies was formed in 1924. This organization was sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company to encourage travel on horseback through the central Canadian Rockies; to encourage life outdoors; to assist in preserving national parks for public enjoyment; and to conserve the native wildlife. The organization meeting was held in Yoho Valley; Dr. C.D. Walcott, of the Smithsonian Institution at Washington, was named honorary president, and J.M. Wardle, chief parks engineer at Banff, was elected president. At this meeting a plaque was unveiled to commemorate the services of Tom Wilson, one of the best known guides in the Rockies, who was believed to be the first white man to see Lake Louise, Emerald Lake and the Yoho Valley. The annual ride, which has been carried on for years, usually involves a five-day outing with overnight stops at prearranged camps, with a final windup at the Banff Springs Hotel or Chateau Lake Louise.

A companion group who preferred to explore the national park trail system on foot was organized in 1933 by J.M. Gibbon, then general publicity agent of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He had the assistance of others interested in hiking, and the group was named the Skyline Trail Hikers. The annual hike is carried out along the lines of the trail rides, with a planned itinerary and overnight stops in tents. These outings are conducted as all-expense tours with everything supplied except clothing and personal effects.

Warden District Organization

After its organization in 1909, the small force of game and fire guardians — since termed the park warden service — grew slowly. For want of roads and trails, early patrols were concentrated on areas paralleling railway lines, where motorized velocipedes were used. Following the opening of the Banff-Calgary coach road in 1911, and the completion of a road to Castle Mountain and Vermilion Pass, the construction of a system of trails and fire roads got under way. Patrols were extended and overnight accommodation provided for the warden staff in the form of patrol cabins. Warden districts were laid out, and permanent warden cabins erected at key points where hunting parties planning to enter park territory might be intercepted. Among the earliest cabins constructed in Banff Park were those on the Kananaskis River and on Panther River in the northeast section of the park. The original Panther River log cabin with its sign Warden Patrol Cabin — Rocky Mountain Park No. 3, was declared an historic building in 1976, and was moved to grounds of the Archives of the Canadian Rockies in Banff towinsite on August 29, 1977. The sign carries the signatures of many of the original wardens who sought shelter within the cabin's walls.

By April, 1914, warden accommodation on park trails had been increased to nine units, and in 1914-15 five more were added. These were at White Man Pass, Healy Creek, Ghost River, Cuthead Creek and Vermilion Pass. As the commissioner of parks observed in his annual report for that year: "The value of these cabins in the forest service can hardly be overestimated. They enable the men to almost indefinitely prolong their patrols when, in other circumstances, they would be compelled to return to town or some other habitation each night."

Current policy was not to restrict the use of cabins to the warden force. They were available to all travellers in the vicinity, subject to reasonable care in their use. As explained by Park Superintendent Clarke in his annual report, the house rules were summarized by a notice in each cabin which read:

In his absence, it may be used by campers, but must be left clean. Any person who takes from this cabin any tool or utensil, except for the purpose of fighting a forest fire, is liable to a fine of $100.8

Early Warden Stations

Most of the early warden headquarters or district cabins were peeled log structures. Usually they were complemented by a separate stable and barn and by an equipment building, sometimes attached to the main residence. Water supply was obtained from wells or by tapping a nearby stream. A supply of firewood usually was available nearby. Lighting was supplied by kerosene lanterns and lamps, later replaced by gasoline lights, and eventually by Delco electric lighting units. Most of the early structures have since disappeared. They have been replaced by attractive bungalows finished in wood siding, and designed to include office space, together with modern plumbing, heating and cooking equipment.

A wardens' workday equipment varied according to the location of his station, but items issued from wardens' stores in each park were bound to include hand pumps, motor-driven fire pumps, axes, shovels, mattocks or grub hoes, crosscut saws, water pails and bags, lanterns and a first aid kit. Small hand tools including files, grinders, a hammer, a handsaw and drills also were supplied. Pumping units might be of either rotary or centrifugal type. Each warden also was issued with a good supply of linen hose for use with fire pumps. Most wardens were provided with one or two riding horses, several packhorses for carrying supplies on patrols, and at least one corral in which to keep their animals from straying. Normal equipment also included a saddle, halters, harness, robes and other equine necessities.

Warden Uniforms

For years, wardens wore no special uniform. Many of the early wardens in the mountain parks were recruited from packers and guides, who favored clothing similar to that worn by men whose duties required the use of horses. Hats invariably were of the cowboy type, although Howard Sibbald and some of his early assistants affected a stiff-brimmed Stetson type hat similar to that used today by boy scouts. Each warden, of course, wore his badge of office.

After long deliberation, the National Parks Bureau in 1938 issued each warden with a formal uniform, designed and tailored by Tip Top Tailors of Toronto, Ontario. The fabric was a dark green wool whipcord topped off by a light brown hat with a semisoft rolled brim. A warden's issue included tunic, breeches, slacks, Stetson hat, badge, riding boots, ankle boots, shirts, belt, ties, parka, raincoat and overalls.9 The uniform was issued to wardens at half the actual cost, the other half being absorbed by the department. Wearing the uniform was mandatory while the warden was on duty, except in special cases when permission for non-use was granted by the park superintendent. Former Chief Warden J.C. Holroyd was issued with badge No. 10, believed to be the lowest number issued. Although withdrawn from service in favor of a bilingual issue, this badge number has been perpetuated, and is still in use in the warden service.

Personnel Expansion

Boundary changes affecting Banff and Jasper Parks from 1911 to 1917 influenced the size of these parks, and also affected the organization of warden districts. The last major boundary changes were made in 1930 with the passing of the National Parks Act. At that time several hundred square miles of territory, considered to be of more value for resource development than for national park purposes were withdrawn. From 1930 onwards, a greatly expanded system of roads, trails and telephone lines helped improve communication between warden stations and park headquarters, making possible a more permanent organization of game and forest protective forces.

Some idea of the increase in warden personnel may be gained from a comparison of permanent and temporary staff positions in 1937 with those in 1957. In 1937-38 department estimates provided for 10 supervising or chief park wardens, 49 permanent park wardens and 13 temporary wardens spread over 17 parks. For 1957-58, the number of park warden positions listed in the annual park estimates included 14 supervising wardens, 72 permanent park wardens and 15 temporary park wardens. The average warden districts in the two largest parks, Banff and Jasper, were 230 and 300 square miles respectively.

Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch

The saddle horse has been an integral part of the national park warden service since its inception. During the formative years of the service, horses provided the principal means of transportation for the wardens, for they were particularly suited for travel on narrow mountain trails where vehicles could not penetrate. As fire roads and improved secondary roads were developed throughout the national park system, the motor vehicle partially supplanted the saddle horse for the transportation of fire fighting equipment, for patrol duties and for personal use, but a substantial number of horses have been maintained in the mountain parks and to a lesser extent in other park regions.

Before 1917 the winter grazing of park horses was carried out at suitable areas either within or outside park boundaries. Since 1917, most horses not retained at various park headquarters have been transferred to an area north of the Red Deer River and just east of the main range of the Canadian Rockies. Known for years as the Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch, it contains an area of 9,750 acres and embraces a beautiful rolling landscape, partly wooded, and covered with prairie grass over several hundred acres. Its name is believed to be the Stoney Assiniboine Indian for "Little Prairie in the Mountains".

Early Occupation

In the early days, access to Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch was from the east by road through the town of Sundre, Alberta, and thence by trail up the valley of the Red Deer River. Later, fire trails and fire roads were constructed north from Lake Minnewanka in Banff National Park up Cascade River, Cuthead Creek, and Wigmore Creek, and over Snow Creek Pass to Red Deer River. The site of the ranch and its amazing possibilities as a horse-grazing area were first brought to the attention of the Department of the Interior in 1904, when Jim and Bill Brewster of Banff applied for a grazing lease in the vicinity; they wished to graze some 300 horses used mainly in Banff and Yoho Parks. The ranch then formed part of Rocky Mountains (Banff) Park, and the application was rejected on the advice of the Departmental legal adviser, as inconsistent with the provisions of the Rocky Mountains Park Act. The Brewsters, however, resubmitted applications for grazing privilieges in 1905 and 1907; the third application, in 1907, was approved by the minister, Frank Oliver.10 A condition of continued operation was a formal survey by the lessee of the land to be covered by a grazing lease.

In March, 1909, the Brewsters had 48 cattle and 150 horses on their ranch, together with a cabin and barns. The ranch, in charge of Frank Sibbald, was used to raise and "break" horses for an extensive guide and outfitting business. Meanwhile, some difficulty had developed in the issue of a grazing lease, although arrears of rental were collected by the park superintendent. By January 10, 1910, a submission to Privy Council recommending the issue of a lease, renewable on a yearly basis, was ready for the signature of the minister, but it was returned to the Superintendent of Forestry, then responsible for park administration, endorsed "No action at present".11

Ranch Withdrawn from Park

In June, 1911, the area of Rocky Mountains Park was substantially reduced, and Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch was left outside the new park boundaries as part of the Rocky Mountains Forest Reserve. Consequently the Forestry Branch of the Department of the Interior took over the administration of the reserve. From 1911 to 1915, national park records contained no correspondence concerning the ranch, although its occupation by the Brewster Trading Company was continued. Early in 1915, Superintendent S.J. Clarke of Rocky Mountains Park advised the Commissioner of Parks that the ranch occupied a strategic position in relation to the protection of the park's wildlife. It was pointed out that the main trail from Banff to Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch ran through the principal breeding grounds of the Rocky Mountain or bighorn sheep. Some of the ranch employees had been convicted in the past of poaching within the park, and Clarke recommended termination of the Brewster grazing privileges which had been enjoyed by permissive lease, although lacking formal documentation. The recommendation was approved by the minister, and the Superintendent of Forestry was instructed to have the ranch property vacated by the occupants, now incorporated as the Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranching Company Limited. L.S. Crosby, a director of the company, requested time to relocate the business; but meanwhile, the Department of the Interior had instructed the Department of Justice to institute legal proceedings to obtain repossession of the ranch lands.

On September 18, 1917, the boundaries of Rocky Mountains Park were extended under authority of an order in council, and Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch again became part of the park.12 Later that year, the Department regained possession and from then onwards, the ranch was used as headquarters of a park warden district, and as a winter grazing area for park horses.

Many years later, the writer discussed with W.A. (Bill) Brewster, his company's use of the ranch. Brewster conceded there may have been some infractions of the park game regulations, but he believed that employees of the Brewster ranch often were blamed for poaching actually carried on by others who had ready access to the area. Meanwhile, the Brewster organization had relocated its ranching activities elsewhere outside park boundaries.

Early Buildings Replaced

Over the years, considerable building construction was carried on in the Ya-Ha-Tinda area by park authorities. A one-room bunkhouse was erected in 1918, along with a garage and a barn with stabling facilities. The bunkhouse was still occupied as staff quarters in 1977. A ranch house, containing a kitchen, living room and two bedrooms was added in 1920. Constructed of logs, it had few modern features. Water came from an outside well, and sanitary features were primitive, providing little comfort to ranch residents in winter.

During World War II, a few buildings were added to the establishment. A one-story log residence for farm laborers was erected in 1942, together with a two-story log barn, incorporating a tack room and stall space for nine horses. The upper story was given over to storage space for oats and hay. A blacksmith shop was built in 1946.

The postwar years witnessed considerably building development in all national parks, and Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch shared some of the funds provided. A frame storage shed for a tractor and other farm implements was built there in 1951. It was complemented in 1952 by another frame building for the storage of fire-suppression equipment, along with storage facilities for gasoline and oil.

A new ranch house built in 1960 for the ranch foreman and his wife undoubtedly brought joy to its occupants. Designed as a fully modern building, it contained three bedrooms, a large living room and a substantial kitchen which served as a mess hall for spring and autumn labor crews engaged in seasonal roundups of horses. The old ranch house was demolished in 1961.

Further additions included a small bungalow hauled to the site from Banff, which was made available to the assistant foreman. It had once formed a unit of the Carrot Creek Bungalow Camp on the Trans-Canada Highway east of Banff. A new powerhouse was constructed in 1960 to house a Delco lighting plant, and in 1963 the ranch acquired a new stable. A quonset building, 34 by 92 feet, it provided stall space for 43 horses. The powerhouse was replaced in 1975 by a metal fire-resistant building.

Jurisdictional Difficulties

When the Transfer of Natural Resources Agreement with Alberta was being negotiated, arrangements were made for substantial reductions in the areas of Banff and Jasper National Parks. These reductions were confirmed by enactment of the National Parks Act in May, 1930. The Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch was included in one of the areas to be withdrawn from Banff Park, but a reservation was made under the Dominion Lands Act on March 14, 1930 by order in council, so that it might be reserved for grazing purposes.13

Provincial authorities for many years thereafter were reluctant to recognize the interest of the federal government in the ranch area, believed to contain 18 square miles. They appeared to be particularly concerned with the ownership of mines and minerals, no doubt because of the interest of individuals and companies engaged in oil exploration. The ranch lies some 1-1/3 miles northeast of the park boundary, and unsuccessful efforts were made with the province to negotiate a corridor that would permit incorporation of the ranch in the park. In 1956 a legal survey of the ranch boundaries was made. By following a strict interpretation of the "metes and bounds" description under which the ranch was reserved for park grazing in 1930, a substantial area of choice grazing land was excluded by the new plan of survey.14

In May, 1956, it was learned that the Province of Alberta had issued a permit for oil and gas exploration in the ranch area. The Department of Justice was requested to provide an opinion on the ownership of mineral rights beneath ranch lands. On June 19, 1956, the Deputy Minister of Justice advised that the national park administration should take the position that the Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch area included the mines and minerals when the ranch was retained by Canada, by virtue of Section 18 of the Natural Resources Agreement with Alberta. Subsequently, the Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources obtained authority from the Governor in Council to enter into an agreement with two Canadian oil companies for the right to explore lands within the ranch for oil and gas.15

Agreement with Province

Eventually, a compromise on land jurisdiction was reached with the province. In September, 1957, Alberta's Deputy Minister of Mines and Minerals, H.H. Sommerville, visited Ottawa and discussed the ownership of mines and minerals beneath the ranch with Assistant Deputy Minister Frank Cunningham of the federal Department of Northern Affairs. They agreed that although the ranch was under reservation when the Transfer of Natural Resources Acts were passed in 1930, there was no real reason for Canada to have retained the mines and minerals. Sommerville suggested that the federal government formally surrender the land comprising the ranch, including mines and minerals, and receive back from the province title to surface rights only.

This proposal was accepted, and, under authority of the Governor General in Council, the administration and control of Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch as described in the 1930 reservation was transferred to the Province of Alberta on February 7, 1958.16 In return, a duplicate certificate of title to the surface area of the ranch dated April 29, 1958 as shown on the latest plan of survey confirmed May 8, 1957, was subsequently received from the province by the director of the National Parks Branch. This action effectively terminated the dispute over the ownership of Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch.

Present Status

Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch now serves a dual purpose. It provides winter grazing for horses transported from the national parks in the Rocky and Selkirk Mountains, and serves as a site for breeding and raising horses suitable for use by the national park warden service. The range will accommodate upwards of 200 horses, which normally are transported by truck to the ranch. Horses are brought from as far west as Glacier and Mount Revelstoke Parks in British Columbia, and from Jasper Park to the north. They are either fed and watered in corrals near the ranch administrative buildings, or moved as required to various ranges to prevent overgrazing.

Records of the horse-breeding activity began in 1938 with the use of a registered thoroughbred stud called September; they have been faithfully maintained since then. Horse breeding was undertaken to improve the quality of horses required to meet the particular needs of the national park warden service. In 1961 Superintendent D.B. Coombs of Banff National Park, accepted the gift of a registered Percheron stallion to the ranch; it was hoped this would produce an improved strain of packhorses. Later, the breeding stock consisted of quarter-horse stallions, registered stallions and a number of suitable mares. Some of the mares were acquired from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police at Fort Walsh, Saskatchewan, primarily because they were not black, and consequently undesirable for police purposes.

For the six-year period from 1960 to 1966 inclusive, the total number of foals born was 133. In 1968, the RCMP closed its remount station at Fort Walsh and re-established it at Pakenham, Ontario. A number cross-bred mares, together with a registered stallion known as Brun, were donated to the National Parks Branch and were transported to Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch. Brun had been a race-horse before being donated to the Police in 1962 by a California sportsman, R.J. McGowan, and prior to his departure from Fort Walsh, had sired 32 foals. After his acquisition by the Superintendent of Banff National Park, Brun assisted in the production of fine offspring, which were trained as riding horses. One of Brun's progeny was from a mare named Minx. This filly, now a brood mare, is a full sister to Burmese, a horse presented to the Queen and ridden by her at the ceremony of Trooping the Color. The sire, Brun, later was destroyed at Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch.

In the normal course of events, foals are taken in hand by ranch personnel at foaling. They are handled, gentled and trained until they reach the age of three years. Then they are allocated to one or more warden districts in the western national parks. A unique method of naming horses born at Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch was adopted in 1964, when all foals born that year were given names commencing with the letter 'A'. The following year, the names of new horses began with the letter 'B', and so on. Hence Isaac was born and named in 1972, and Morgan in 1976. Consequently, their ages can quickly be determined from their names.

The ranch area is shared with the park horses by a large herd of native elk, which has been known to number as many as 1,200 at one time. This intrusion of game animals from Banff National Park and adjacent provincial lands sometimes places considerable pressure on the available forage. In 1962 a special hunting season for elk was opened by the Alberta Fish and Wildlife Service to save the winter pasture. The hunting of elk during the provincial hunting season has since been encouraged, although hunters must confine their use of privately-owned vehicles to the road through the ranch.

Public Use of Ranch

Public use of the ranch for recreation other than hunting has increased consistent with the improvement of the access road from Sundre to the east. In turn, road improvement followed gas and oil exploration by drilling. Three wells drilled between 1951 and 1976 proved unsuccessful. All were in the vicinity but not on the ranch property.

Camping, hiking, riding and fishing are among the recreations enjoyed by visitors in a beautiful setting. A rudimentary campground was established on Bighorn Creek in 1960. Most visitors are drawn from Alberta although residents of the United States and Europe now are finding their way to the ranch. Visitors are not permitted to graze their horses on ranch land, but are free to ride the range at will.

The warden service has maintained a deep interest in Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch over the years, for it is there that one of a warden's most faithful helpmates — the horse — is born, trained and wintered. In the mountain parks of western Canada, and in Elk Island Park, horses are still the principal means of transportation for back-country travel. Through close association, a deep and lasting affection exists among wardens for their horses.

Park Warden Training

When Howard Sibbald organized the first group of men to serve as fire patrolmen and game protection officers in 1909, the force was called the Fire and Game Warden Service. Wardens then were gathered from various walks of life, but principally from guides and packers, to perform briefly outlined duties in districts larger than some of our present-day national parks. The work took them along railway lines by motorized velocipede, over roads and trails by horse, on foot or by canoe in summer. In winter, patrols were accomplished on snowshoes. Headquarters or district cabins were widely separated, and patrol cabins sometimes were built by wardens to their personal needs. A notable cabin-builder was E.W. "Bill" Peyto, who served as a warden in Banff National Park from 1918 to 1933. Before his service as a warden, Peyto was one of the best-known guides and packers in the central Rockies; and in the course of his prospecting excursions he discovered a large deposit of talc southwest of Redearth Creek in what is now Kootenay National Park. More about this deposit and its development as a mine will be found in the next chapter.

After World War I, increased travel to the national parks and greater use of roads and trails indicated a need to extend protection to visitors as well as to the creatures of the wild. Recognition of this need expanded the field of park warden activity. It was realized that the duties and functions of park wardens would become more complex, and in turn require the development of special skills and abilities through proper training.

First Warden Schools

The first warden training school was held in Rocky Mountains (Banff) Park in 1925. The early schools gave instruction not only in the use of hand tools and fire hose but also in the use of "newfangled" equipment such as motor-driven fire pumps, automobiles and fire trucks. Qualified instructors, however, were few in number. One superintendent overcame this problem by escorting driver trainees to a local well-fenced race track. The warden in training and his motorized mount were then detained in the enclosure until his driving performance brought no more cheers from the spectators.17

By 1928 a number of parks were holding annual refresher training classes, some of them in alternating sessions of one week's duration. The scope of the training classes was extended to include field telephone maintenance, trail construction methods, wildlife management, first aid and horse packing. In Banff Park, the schools concluded with a wardens' annual rifle shoot. During the early 1940s general warden training classes covered a wide range of subjects, and guest lecturers were invited to provide instruction in various fields. A few shortwave radios capable of two-way communication had been acquired, and in some parks these were a source of interest and bewilderment. The first regional warden school was held at Banff in 1942, when arrangements were made for attendance by wardens from the four national parks in British Columbia.

Training for wardens involving a broader outlook took form during the following decade. In 1950 and in 1951, composite conservation schools were convened at the Banff School of Fine Arts in Banff for wardens from the western national parks, the Yukon and Northwest Territories, and for rangers from the Alberta Forest Service. The session continued for almost one month. This training scheme, however, was abandoned when the Alberta Forestry Service withdrew its representation to concentrate on a Forestry Training School at the provincial level.

Snowcraft Schools

The first national parks ski and snowcraft school was held in Yoho National Park, British Columbia, early in 1949, attended by wardens from Banff and Yoho Parks. In 1951, the school was held in Glacier National Park British Columbia. Wardens in attendance were provided with the latest equipment in boots, skis and poles, and were given a rigorous course by qualified instructors. In the years following, the ski school was held in either Banff or Glacier National Park.

In February, 1955, three wardens from the mountain national parks in Canada were sent to Alta, Utah, for an avalanche rescue course. On their return, a winter training school was held at Banff where, in addition to alpine ski training, basic instruction was provided in the causes and results of avalanches, and methods of avalanche rescue work.

During the ensuing years, this form of rescue training has taken on a wider implication. The development of additional ski centres in the national parks of the Canadian Rockies has attracted thousands of winter visitors interested in this sport. However, in spite of an intensive educational program about the dangers in avalanche-prone areas, casualties still occur among skiers who venture into areas designated unsafe. Rescue equipment is maintained in the vicinity of all developed ski areas, and skiers travelling afield are warned to register with park wardens and to ascertain the location of field telephone stations from which to call for assistance.

Mountain Rescue Responsibility

The popularity of mountain climbing with visitors unskilled in the sport became apparent in the early 1950s. This development also added responsibilities to the national park warden service, in rescuing stranded or injured climbers. For many years the superintendents of Banff, Yoho and Glacier parks — which were centres for activities sponsored by the Alpine Club of Canada — relied on the professional guide service maintained by Canadian Pacific Railway Company for assistance in emergencies. Its guides, recruited mainly from Switzerland, had served the needs of guests at the company's mountain hotels since 1899. They were stationed originally at Glacier House hotel in Glacier Park. After this famous hostelry was closed in 1925, the guides were relocated at Chateau Lake Louise. The families of the guides lived in a small colony two miles west of Golden, British Columbia, known as Edelweiss.

Early Swiss Guides

The first Swiss guide to climb in the Selkirk Mountains was Peter Sarbach of Zermatt, Switzerland, who accompanied a few members of the Alpine Club of Great Britain to Glacier and Banff in 1897. Sarbach's visit is commemorated by Mount Sarbach on the Banff-Jasper Highway. In 1899 the CPR brought out Edward Feuz and Christian Hasler from Interlaken, Switzerland, to Glacier House. The following year, Hasler was detailed to the Mount Stephen Hotel at Field in Yoho Park, and Edward Feuz was joined at Glacier by Karl Schlunnegar, Frederick Mitchell and Jacob Muller. In subsequent years these guides were followed by others, some of them lineal descendants of members of the original group. They included Edward Feuz, Jr. (1903), his brothers Ernest (1909) and Walter (1912); and Christian Hasler, Jr. (1912). Another notable addition was Rudolf Aemmer in 1912.18 Following World War II, mountain climbing held less attraction for the hotel guests, and replacements for the older professional guides were becoming hard to obtain. The third generation of the original guides showed no interest in following the occupation of their fathers, and in 1950, the CPR recruited Walter Perren and Edmond Petrig as the last guides from Europe to supplement the remaining guide staff. In 1954 the railway company learned that Walter Perren, the chief guide, was not prepared to renew his contract when it expired the following year. In view of the difficulty experienced in recruiting a suitable replacement, the company decided to discontinue its guide service in 1955.

Spectacular Rescues

Over the years the Swiss guides conducted visitors on innumerable climbs, and also participated, in cooperation with park wardens, in the rescue of persons injured or trapped at high altitudes. In 1954 one of the most tragic alpine accidents on record in the Canadian Rockies occurred on the south peak of Mount Victoria, at the western end of Lake Louise. On July 30 a group of young women from Mexico, accompanied by a Mexican guide, Eduardo Sanvincente, completed the ascent of the south peak of the mountain from the alpine hut in Abbot's Pass between Mounts Victoria and Lefroy. The climbing party, on two ropes, had made the final ascent up the steep eastern snow-covered face of the peak, rather than by a longer but safer route along the rock ridge from the summit of the pass. All were equipped with crampons on their boots, which provided good footing on ice and hard snow, but were useless on snow which had warmed and softened in the sun. While retracing their route down the steep face of the peak, one of three women roped to the guide lost her footing in the snow and fell. In so doing she pulled the others down. The entire party of four then slid down the precipitous slope and over a precipice to Lefroy Glacier, 2000 feet below. All were killed. The remaining three climbers on the other rope, now unable to obtain a secure footing, remained on the slope in hope of rescue.19

The accident had been witnessed through binoculars by an employee of Brewster Transport at Chateau Lake Louise. Walter Feuz, one of the staff employed at the hotel, also had been following the progress of the climbers with the aid of binoculars, and noticed that only three of the seven were still on the mountain face. The accident was reported promptly to the hotel manager who organized a search and rescue party. The rescuers, headed by guide Ernest Feuz, were transported up the lake by boat to its western end by Walter Feuz. They located the bodies of the climbers in Abbot Pass, and proceeded up to the alpine hut. Here they found an eighth member of the party, who had not participated in the climb, and who not only was unaware of the accident but spoke no English.

Ernest Feuz, who had an intimate knowledge of the peak, made the final rescue dash, accompanied by Charles Rowland, a summer employee at Chateau Lake Louise. Normally a one-hour climb, it was accomplished in 35 minutes. They reached the three stranded members of the climbing party shortly after 7 p.m. and had them back in the alpine hut at 9.40 p.m. Later all four women were escorted down to the tea house at the foot of the Plain of Six Glaciers, where they were fed and put to bed. Although all of the victims, including the guide, were experienced climbers, apparently their ignorance of changeable conditions on steep snow-covered slopes in the Rockies contributed to the accident.20

Tragedy on Mount Temple

On July 11, 1955, another regrettable incident occurred on Mount Temple, near Moraine Lake in Banff National Park. A group of 16 boys, members of the Wilderness Club of Philadelphia, were caught high up on the slopes of the mountain by an avalanche, which took the lives of seven of the party. Although the mountain, which rises to a height of 11,636 feet above sea level and 5,400 feet above Moraine Lake, is not rated as a difficult climb, avalanche conditions prevail in early summer, and climbs undertaken without expert guidance can be hazardous.

Accompanied by the camp counselor, William Oeser, the 16 boys made their way up to the 8,500 foot mark, where the counselor and five boys dropped out. The remaining 11, under the leadership of two 16-year-old boys, decided to press on. On reaching an elevation of 9,500 feet, the party sensed danger from the sound of falling avalanches and turned back. Outfitted only in summer clothing, and equipped with only two light manila ropes, the group was engulfed in a small avalanche which buried four boys, injured three and left the others in various states of shock. One boy, Peter Smith, was sent down the mountain for help, and on the way informed the counsellor of the accident. About an hour after the accident Smith reached Moraine Lake, where park warden Woodworth began organizing a rescue party of experienced mountaineers. Two wardens, Gilstrof and Schuarte, reached the avalanche site ahead of the main party, and Gilstrof started down the mountain with one boy on his back.

Later, wardens Perren and Pittaway jointed Schuarte, who had made progress in digging out the missing boys. A second rescue party, under chief warden Herb Ashley, joined the search, and by 3 a.m., all seven victims had been accounted for, including one boy who had died from exposure to cold and rain. The rescue mission was completed by 7 a.m. the day after the accident.

A coroner's inquest revealed that the party was inadequately dressed for the climb, that no prior information on the route of the proposed climb had been obtained, that the ropes carried were below the standard required for mountain climbing, and that the party had failed to register out with the Moraine Lake park warden as required by park regulations. The coroner concluded that the boys were the victims of their own youthful enthusiasm and inexperience.21

Stricter Park Regulations

The Mount Victoria accident, together with other incidents requiring the assistance of park wardens and others in rescue operations, prompted national park authorities to review existing regulations governing field outings and climbs. For many years, park visitors who proposed excursions in areas of national parks distant from highways were required to register out at places provided by the park superintendent, usually at a park warden station. In December, 1954, the existing regulation was amended to include mountain climbing. As revised, the regulation required any person planning to climb a mountain "before departure to register with the Superintendent or at such place as may be provided by the Superintendent, the names and addresses of the members of the party, the date of departure, the route to be traveled, the proposed duration of their stay in such park...and such other information as may be required by the Superintendent".22 In effect, the district park warden would have prior knowledge of any excursion involving danger and also have some idea of when the return of the person registered might be expected.

Climbing Expert Engaged

After the Canadian Pacific Railway Company disbanded its Swiss guide service in 1955, Walter Perren was engaged by the superintendent of Banff Park on May 1 as a member of the park warden service. His first assignment was to initiate a mountain climbing and rescue program for park wardens. The first rescue school was held in June, 1955, at Cuthead in Banff National Park. The second, which was attended by several members of the RCMP, was held the following October. Similar schools were repeated annually under the direction of Chief Warden Perren until his death in 1967.

The schools usually took the form of two-week sessions with about 30 students in attendance. Wardens with little or no climbing experience were first taught the basic skills. In following stages the wardens were advanced, with the use of suitable equipment, to the point where they could participate in a difficult climb, or serve as a member of a climbing party or rescue team. The final stage involved further experience and instruction that would qualify a warden to lead a climbing party or direct a rescue operation.

Death Takes a Holiday

By 1961 the wardens who had graduated from the climbing and rescue school had reached a high state of proficiency. While none would claim that the graduates filled the climbing boots of the former Swiss guides, they completed some notable rescues. Their activities also influenced compliance by alpine-oriented visitors with park climbing regulations. During 1961 some 1245 parties registered out under the regulation for climbs in Banff National Park — twice the number recorded in 1955. A spectacular rescue, carried out five years later in August 1966, involved Chief Warden Perren and District Warden Walter McPhee of Banff Park. Two experienced climbers from Calgary became marooned on Mount Babel, a 10,175-foot peak between Moraine and Consolation Lakes in the Lake Louise District. One climber had slipped, fallen and broken his wrist. Both men by then were trapped on a spike-like ledge. Cries for help reached the ears of another party in the vicinity, and help was summoned through the district warden. A rescue team was then airlifted by helicopter to a landing site on the mountain within access of an anchor area. Warden Bill Vroom was lowered by block and tackle in a Gramminger seat — a form of bosun's chair — over a 150-foot overhang. Later he was brought up again with the injured man in the seat. A second descent followed, and, with the aid of the tackle and seat, the second climber and his rescuer were winched up the precipice to safety. The formal report of the incident finished with the words: "Although blessed with good weather, unbeatable men and fine equipment, the rescue crew in their ultimate success offered a silent prayer, thankful that death had taken a holiday."23

Warden training and techniques are under constant scrutiny to minimize hazards and improve the rescue service. The highest number of rescues carried out in any single year in the western parks was 134, a record established by the warden service in 1975. At the time of writing Parks Canada was the only organization in North America allowed to belong to the International Commission of Alpine Rescue.

Training in Atlantic Parks

Composite training for national park wardens was extended to staff of the Atlantic parks in the winter of 1954, when the first warden school in that region was held in Fundy National Park, New Brunswick. Frank A. Bryant, superintendent of Kootenay National Park, who for many years had been a park warden and a chief park warden, presided as officer in charge. The course, which extended from February 22 to March 3, covered a wide variety of subjects in addition to practical warden training. Talks, followed by question periods, on park history and administration, wildlife conservation, forestry and fire prevention practices were given by officers of the National Parks Branch from Ottawa. An officer of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police also lectured on the role of a park warden as a police officer. Altogether nine wardens from three Atlantic parks — Cape Breton Highlands, Prince Edward Island and Fundy — were in attendance.

Two years later, in September 1956, the second school for wardens in the Atlantic provinces also was held in Fundy Park, under the direction of D.J. Learmonth, national parks forester at Ottawa. Besides personnel from the Atlantic parks, the school was attended by three wardens from Gatineau Park near Ottawa, which is administered by the National Capital Commission. Later, following the establishment of an Atlantic regional office at Halifax, warden schools were held on an annual basis at various parks within the region.

Annual Warden Gymkhana

The ancient adage, "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" applies to park wardens as it does to everyone else. And this was reason enough for an annual horse gymkhana staged by the wardens of the mountain national parks for several years at Hillsdale, in Banff National Park. The gathering was conceived by warden Wally McPhee of the Banff park warden service, during the annual roundup of park horses and their transfer to winter grazing grounds at Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch northeast of Banff. During overnight stays with wardens along the route to the ranch, McPhee found that conversations usually led to talk on the abilities of their favorite horses. Bragging led to arguments, and arguments to challenges. McPhee entered a few private contests before realizing that a fair comparison of horses could be made only by simultaneous competition under uniform conditions.24 The basic concept was that the wardens should get together to demonstrate the ability of both men and horses in a spirit of friendly competition. Events staged should demonstrate skills and knowledge related to the duties and activities of a park warden.

A committee of wardens organized the first competition in 1963, held at Ya-Ha-Tinda Ranch. After a second gymkhana on the same site in 1964, interest was so great that a more central location was sought. A large natural clearing known as Hillsdale, 12 miles west of Banff, provided an ideal site for the annual event during the next seven years. The events involved the use of both riding and pack horses. Occasionally, wives or lady friends of the wardens took part in mounted versions of the egg-and-spoon race and other contests. These gatherings not only encouraged the wardens to take more interest in their horses, but also provided an opportunity for all park staff to engage in an annual get-together.

Hazards of Employment

Improved means of communication, better roads and trails, modern accommodation and an increased use of motor vehicles all have changed the day-to-day life of a park warden. Those employed on rescue missions, or detailed to perform one of many other hazardous tasks, run some risk of personal injury or even loss of life. Fortunately, casualties have been rare during the past few decades. Some 40 years ago, however, the hazards of employment encountered by wardens were more pronounced.

In September 1929 Percy Hamilton Goodair, a Jasper Park warden, was killed by a grizzly bear. Stationed in Tonquin Valley, some 16 miles by road and trail from Jasper towinsite, Warden Goodair had failed to make his usual report by field telephone to the chief park warden's office in Jasper. A search party organized by the park superintendent found Goodair lying dead under two feet of fresh snow not far from his district cabin. A detailed examination of the area around his cabin, suggested an unexpected confrontation with a female grizzly bear.

Goodair had maintained a woodpile down a path from his cabin. An inquest at Jasper concluded that on his way for fuel the warden had suddenly met a grizzly. The presence of a sow bear with two cubs in the valley that summer had been known, and it was presumed that during a snowfall, the warden had unknowingly come between the mother bear and its offspring. Apparently the bear had lashed out with deadly claws and severed an artery under Goodair's arm. The warden had made a vain effort to plug the wound with a coloured sash that he habitually wore, but had collapsed on the trail before he could reach the cabin and telephone for help.

Among Goodair's effects was found a note expressing the wish that, should any unforeseen calamity befall him, he might be buried in the wilderness he loved. His wish received the approval of the Commissioner of Parks in Ottawa, and Goodair lies buried on a site near the now-vanished cabin which overlooked the spectacular Amethyst Lakes. A commemorative stone, set in a chained-off enclosure, records his name, his life-span (1877-1929) and the epitaph, "We cherish his memory in our hearts."25

Murder at Riding Mountain

Another fatality which occurred in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, on July 13, 1932, has remained an unsolved crime. Park warden Lawrence Lee, stationed at the Russell (now Deep Lake) station, was shot dead through a kitchen window while eating his evening meal. His wife, a bride for only five days, also was gunned down by the unknown assailant but survived the ordeal.

Earlier that day, Lee was visited by a friend, Bob Hand, who later became a park warden. During their discussion they heard the sound of a gunshot in the vicinity of the park boundary to the southwest. Lee left to investigate, while Hand rode north towards Birdtail Valley, where he was checking cattle grazing under permit. After his return, Lee completed a few chores and sat down to dinner in the kitchen. While eating he was shot dead through a window that looked out over a woodpile four feet high.26

Mrs. Lee ran to the telephone connected with park headquarters and managed to complete a call for help before she too was shot in the jaw through another open window. As recalled later by Mrs. Lee, the murderer then entered the room through the window, stepped over the prostrate body of the injured woman, and entered the warden's office. There he tore three pages from the warden's diary and disappeared. Mrs. Lee survived the shooting, and was able to assist Superintendent Smart and officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the intensive investigation that followed. She was able to describe the intruder as he appeared from the waist down as she lay on the floor, but his identification and apprehension proved impossible. While no clues to a motive for the crime were found, it is quite possible that the assailant was a resident of a settled area south of the park boundary, from which game-poaching activities were frequently launched. After recovery Mrs. Lee moved to Winnipeg, and engaged in newspaper work with the Free Press Prairie Farmer.

Hunting the Hunted

In October 1935 a park warden became a member of a posse organized to hunt for the murderers of two policemen in Banff National Park. Three young Doukhobors named Posnikoff, Voiken and Kalmanoff, suspected of shopbreaking, were picked up by two RCMP officers at Benito, Manitoba, in the early hours of Saturday, October 5. On the way to Pelly, Saskatchewan, for questioning, the suspects disarmed and killed their escorts, Constables Shaw and Wainwright, and drove off in the blood-spattered car after dumping their bodies in a ditch.

By nightfall a description of the missing officers and their car had been broadcast. On Monday the bodies of the missing police officers were discovered. The trail of the fugitives was traced to Exshaw, Alberta, when they had purchased gasoline. Police at Canmore and Banff were advised that men answering the descriptions of those wanted were in the neighborhood. A road block was set up on the main highway between the two towns, and the missing car and men were intercepted. In a shoot-out that followed, an RCMP sergeant was killed and a constable fatally wounded. The ringleader of the group, Posnikoff, also was killed by gunfire, but the other two took to the woods.

The day following, a band of armed citizens from Banff set out in a whirling snowstorm, intent on capturing the murderers alive. Park warden Bill Neish, stationed at Mosquito Creek on the Banff-Jasper Highway, heard of the impending manhunt on the radio and determined to take part. Without obtaining permission from the chief park warden, he left for Banff that night. On the following morning he saw two men crossing a clearing and called on them to stop. Neither paid any heed to the command, and Neish brought one man down with his first shot. The other fugitive opened fire on Neish from the cover of a fallen tree. Neish responded with a shot through the tree that disabled his antagonist. Both wounded men were brought into Banff, where they died in hospital. According to Dan McCowan, a noted author and lecturer who lived at Banff for years, Neish's monthly diary for October, 1935, aroused considerable interest when it reached the National Parks Branch at Ottawa for review. Opposite the date of October 8 was the entry "killed two bandits". Not being familiar with the events of that day in faraway Banff National Park, the officer responsible for a review of the diaries requested additional information. Back came a terse supplement, "Snowing to beat Hell."27

Dangers Still Remain

The foregoing examples of the risks, dangers and misfortunes that may confront park wardens are unusual or extreme. But they demonstrate that the nature of their work entails exposure to hazards of many kinds. In December 1972 wardens Marak and Brink lost their lives in a highway accident while on routine patrol in Banff National Park west of Lake Louise. A coroner's inquest blamed ice on the highway for the accident.

Rescue work for wardens usually begins when some member of the public has failed to exercise, care, judgment or plain common sense. Undue familiarity with wild animals, although forbidden, still occurs with regrettable results. Weather, carelessness or ignorance of park regulations can also contribute to accidents. Misfortune in various forms may visit even a warden, and if negligent, his pride suffers accordingly. Nevertheless the hazards of employment are a challenge that bring individual wardens together as a team.

Combatting Forest Fires

An ever-present threat to our national parks is forest fires which, from the earliest days of exploration, have ravaged these areas. Conflagrations which marred the landscape and despoiled the habitat of native wildlife have been attributed to various causes. Some have been caused, perhaps unwittingly, by the hand of man. Untended camp fires, the careless use of matches and tobacco products, and, in earlier days, sparks from locomotives, have touched off untold numbers of blazes. Other fires have been the result of deliberate incendiarism. On the other hand, many of the most hard-fought fires had their origin in lightning strikes, especially in periods of extreme drought and heat, when even a spark might touch off a bonfire. Whatever their origin, all fires in national parks are of particular concern to the warden service.

For years, one of the most conspicuous landmarks at Banff in Banff National Park was a fire burn on the north slope of Sulphur Mountain. It occurred late in the 19th century, and even today the outline of the burned-over area, stretching more than a mile up the wooded slope above the townsite, is visible in a lighter shade of green where newer growth has regenerated the devastated area. The sites of many other fires have also recovered their verdure, but one of the latest, which occurred in the vicinity of Vermilion Pass in 1968, will take years to heal.

Kootenay Park Holocaust

During the half-century since its establishment, Kootenay National Park in British Columbia has experienced two memorable fires. The first, long known as the "great fire", started on July 6, 1926, on the Upper Kootenay River, about four miles northwest of Kootenay Crossing on the Banff-Windermere Highway. This fire was the tenth outbreak to occur in a hot dry summer in that park, and it raged for nearly six weeks during which no rain fell. Early efforts of an emergency crew to control the fire were nullified by a 30-mile an hour wind. After crowning, the fire swept south to the Banff-Windermere Highway, which follows the valleys of the Vermilion and Kootenay Rivers. Fanned by a prevailing wind, the fire then roared north and east into the Vermilion River valley. It also jumped the Kootenay River and burned south along both banks. Before it was checked, the fire had swept up the Vermilion River for several miles, and south along the Kootenay River for another four.

Altogether, a timbered area of approximately 15,000 acres was burned before the fire was brought under control. More than 200 men were recruited from all ranks of the National Park Service as fire-fighters. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company contributed the services of 30 men, together with trucks and hose, who were joined by volunteers from the Columbia River valley and from points as far east as Calgary. Operations were directed by park superintendent Howard Sibbald and chief engineer J.M. Wardle. In the course of the fire, the Banff-Windermere Highway was closed for a short period. Through the efforts of the firefighters, all bridges, park warden stations and other buildings in the area were saved from destruction.

On the seventh day of the fire, July 13, a tragedy occurred. A four-door automobile driven by L.I. Watt of Edmonton, containing his wife, two children and Mr. and Mrs. Clifford Nesbitt, entered the fire zone en route from Vancouver to Edmonton, by way of the Banff-Windermere Highway. They had been warned that driving was hazardous, and after crossing the Kootenay River bridge the party encountered heavy smoke. They decided to turn back and eventually pulled up against a cut-bank where heavy windfall bordered the highway. According to a report forwarded to Ottawa by chief engineer Wardle from Banff, the women did not wish to leave the car, but the two men set out to find a small lake or pond that would offer shelter. Later the two men were rescued by members of the fire crew, but the women and children died from burns, shock and suffocation. Subsequent investigation disclosed that, had the party driven on a short distance from where they had turned back, they could have taken shelter in either a highway culvert or a small pond.28

Drought and high winds continued for the duration of the fire, which was fought almost exclusively by muscle power, portable fire-fighting units and other equipment developed by the National Parks Service. In his annual report for 1926-27, Commissioner of Parks J.B. Harkin called attention to the devotion to duty by parks personnel during the fire, and observed that "the superintendent was in charge of the operation and for six weeks was never in bed."29 The fireswept area, over a period of 30 years, was completely regenerated by a heavy growth of lodgepole pine. Only the lighter tone of the new forest cover revealed the location and extent of one of the biggest fires in Canada's national parks.

Fire Again Strikes Kootenay

From 1956 to 1965 several fires were kindled by lightning strikes in Kootenay Park, but the only significant one was that which burned over an area of about 22 acres on the slopes of Storm Mountain southeast of the Banff-Windermere Highway in July 1961. It was brought under control after two days of hard work by the park wardens. Seven years later this popular park was visited by a second holocaust which, in intensity and in rapidity of advance, rivalled that of 1926.

On the afternoon of July 9, 1968, thunderheads and lightning, but no rain, were observed at Marble Canyon campground, four miles south of the park boundary at Vermilion Pass. John Royko, a campground attendant, recalled a clap of thunder and a flash of lightning a few minutes before he saw a fire burning up on the lower slope of Mount Whymper northwest of the campground. Almost simultaneously, park warden Ron Morrison spotted the fire from the Marble Canyon warden station. After reporting the fire to Warden Hanley at Kootenay Crossing, Morrison loaded hand tools into his truck, picked up Royko and an assistant, and headed for the fire. Meanwhile park headquarters at Radium Hot Springs had been alerted, and by late afternoon a fire crew of 13 men in charge of Warden Winkler from Sinclair Canyon had arrived at the fire.30

Fire Advances Rapidly

By early evening the fire had spread to an area of 600 acres, in spite of the efforts of Morrison, Hanley and three assistants. Prevailing wind and heat precluded any hope of getting in front of the fire, and efforts were made to head off the blaze on northwest and southeast flanks. More fire pumps were brought into action, but with little success in an area filled with dead timber. Meanwhile Winkler had requested help from Banff National Park in the form of men and tractors. Later about 35 men in charge of Chief Park Warden Corrigal arrived from Banff, and the combined fire crews and equipment were brought into action.

On the morning of the second day of the fire, July 10, a crew of 68 men, three tractors and numerous power pumps and hand tools were used to fight the fire. Additional fire fighters were obtained from Banff and from Cranbrook, British Columbia. The possibility of using water bombers from a temporary base on the Trans-Canada Highway also was investigated. By afternoon, the fire had advanced up Vermilion River Valley and crossed into Banff National Park. By this time three aircraft equipped for water bombing and two observation planes had arrived at a temporary landing strip on the Trans-Canada near Taylor Creek.

Hikers Rescued

That same day a hiker and two children were rescued from an area near Stanley Glacier in the northeast section of Kootenay Park. The presence of the party in what was considered a hazardous area was reported to the fire crew by the man's wife, who was parked in an automobile beside the highway near the start of a walking trail to the glacier. After the fire jumped the highway to the northeast side, a helicopter was flown in to evacuate the man and his children.

On the fourth day of the fire, July 12, fire crews were augmented by 125 men from Canada's armed forces, who manned water tankers operating along the Banff-Windermere Highway and the Storm Mountain fire line east of Vermilion Pass. That day, too, all fire control operations were merged under Steve Kun, superintendent of Banff Park, who was a professional forester. Kun assumed control of the allocation of supplies, manpower and equipment between the Banff and Kootenay fronts of the fire, and was responsible for reports to regional headquarters. By this time Nature was lending a helping hand; cloudy and cooler weather combined with falling rain to clear much of the smoke and reduce the overall effort required.

Fire Contained

On Saturday, July 13, the fire was largely in check, although occasional water bombing and helicopter water drops were being made where flare-ups occurred. The Canadian army personnel were released on Monday, July 15, and three days later fire crew personnel had been reduced to 30 men with six held in reserve. By Saturday, July 20, all aircraft had been released and the operation had been shifted from fire-fighting to cleanup. Transient workers were dispersed the following day, and most of the park personnel returned to normal duties. Altogether, the fire had consumed about 6,500 acres of timbered land. Of this area, about 70 percent lay within Kootenay Park and the rest in Banff Park.