Volume IV

by W.F. Lothian

Chapter 7

Preserving Canada's Wildlife

Introduction

Although Canada's first national park reservation was made in 1885 to ensure public ownership of the mineral hot springs which had been discovered near Banff Station, steps to preserve other features of the natural environment in the Canadian cordillera had already been taken. In 1883, the Dominion Lands Act had been incorporated in the Statutes of Canada in order to permit orderly and competent administration of the vast expanse of public land lying between the Ontario-Manitoba boundary and the Canadian Rockies. One year later, the Government of Canada made provision, by an amendment to the act, for the creation of "forest parks." The object of this legislation was 'the preservation of forest trees on the crests and slopes of the Rocky Mountains, and for the proper maintenance throughout the year of the volume of water in the rivers and streams which have their sources in the mountains and traverse the Northwest Territories'.1

Although the areas affected were then remote and practically inaccessible to the average Canadian, the legislators of the day undoubtedly were giving thought to the future, when the existing stretches of wilderness would be traversed first by railways, and later by highways. Improved access in turn would attract settlement and the development of natural resources, with consequent impairment of the landscape and unavoidable depletion of the water resources which today are so carefully guarded. A few years later, this clause of the Dominion Lands Act was employed to reserve as forest or mountain parks, areas which now are included within the boundaries of Glacier, Yoho, Jasper and Waterton Lakes National Parks.

Following the creation of the Hot Springs Reservation at Banff in 1885 under another section of the Dominion Lands Act, conservation measures were limited to preservation of the springs and the surrounding forests. However, by May, 1886, the Minister of the Interior, Thomas White, had approved a recommendation of George A. Stewart, Dominion Lands Surveyor, that the reservation be expanded west, north and east of the hot springs, and that the enlarged area be established as a national park. Stewart was instructed to extend his survey, and on completion, his plan incorporated an area of 260 square miles. As outlined in the first chapter of this history, Rocky Mountains Park came into being on June 23, 1887.

Michel Pablo and his cowboys who herded and corralled 716 buffalo for shipment to Canada. circa 1907

Some of Pablo's buffalo on the Flathead Reservation.

Jasper Park fish hatchery superintendent Bill Cable with visitors at a rearing pond.

Early Conservation Measures

Anticipating the establishment of an enlarged park, the Minister in 1886 had engaged the services of W.F. Whitcher, formerly Commissioner of Fisheries at Ottawa, to undertake an examination of the proposed area and submit recommendations for the protection of the wild game, birds and fish found there. Whitcher's report, dated December 1, 1886, was received in time to be included in the annual report of the department for that year.2 It reviewed the status of the game animals, fish and migratory birds in the proposed park, and included recommendations for increasing the numbers of species which had been depleted by uncontrolled hunting during the period of railway construction. The report also called for the strict control of hunting, shooting, trapping and fishing, and proposed means of restocking lakes and streams with suitable varieties of fish. Whitcher commented on the wasteful destruction of game fish by netting, dynamiting and improvident fishing in the immediate past.

Among the projects undertaken later by Superintendent Stewart was the planting of wild rice in the creeks, ponds and sloughs of the Banff area, including the Vermilion Lakes. A small tree nursery was established at the foot of Cascade Mountain, using a reservoir fed by the cascading waterfall for watering the nursery stock. The project however, failed miserably on the site selected, and a large number of young trees which had been purchased in the northwestern United States were replanted in the vicinity of the Spray River.

Whitcher had expressed concern over the need for fire protection in the vicinity of Banff. The Bow River Valley to the west had been ravaged by frequent fires, and many of them had burned unchecked during the period of railway construction. After the rail service was inaugurated, there still remained a constant danger from sparks thrown out of the locomotives. Whitcher's report proposed firebreaks, and the construction of dams and weirs along the Bow River which would flood adjoining marshes and sloughs and provide effective fire-breaks west of Banff Station.

Remedial Action Taken

In drafting the Rocky Mountains Park Act, the legal adviser of the department incorporated a number of the recommendations made by Whitcher. Provision was made for the enactment of regulations which would permit "the care, preservation and management of the park and of the water-courses, lakes, trees and shrubbery, minerals, curiosities and other matters therein contained". Also provided for was "the preservation and protection of game and fish, or of wild birds generally. . ." These sections of the Rocky Mountains Park Act were translated into park regulations in November, 1889. They required park residents and visitors to exercise care in the lighting and extinguishing of campfires; prohibited the defacement of natural rock formations or curiosities; outlawed the wounding, capturing or killing of wild animals and birds; and limited fishing to that possible by rod and line. The use of firearms within the park, except under permit from the park superintendent, also was prohibited.3

Although statutory authority for forest and wildlife protection now existed, a limited budget and a shortage of manpower hampered the efforts of the park superintendent and his staff. Fire breaks were cut through the woods near Banff in 1889, and in 1891, the road serving the Cave and Basin Springs was extended to Sun Dance Canyon, chiefly for its value as a fire break. The park superintendent had on his staff one officer designated "fire ranger" in the person of John Connor, who resided in Banff. Occasionally Connor had to double as an office assistant. He died in November, 1890, and no record of his replacement as forest ranger has been found. Firefighting became an emergent duty for all park employees and any one else who was available. In his report for 1891, the superintendent stated that a fire bearing down on the villa lot section of the embryo townsite was arrested only after all government staff turned out to repel it.

Game Protection Difficulties

The enlargement of the park area in 1902 from 260 square miles to about 4,400 square miles by an amendment to the Rocky Mountains Park Act, culminated an aggressive campaign carried on by Superintendent Howard Douglas for several years. The park extension, however, added substantially to his administrative problems. It also revealed that much of the wildlife it should have supported had been decimated. In his annual report for 1903, Douglas complained bitterly about the scarcity of game along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. This situation he attributed to hunting carried on by the Stoney Indians. His views on the matter were set out as follows:

"Twenty years ago, the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains from the Kicking Horse Pass to the boundary line (international), was filled with game. Moose were frequently seen, elk and black tail deer, white tail deer, bighorns and goats were plentiful; now some of these have totally disappeared and the remainder have been so thinned out as to make this hunting ground practically valueless."

"The Stoney Indians are primarily responsible for this condition of affairs. They are very keen hunters, and always have been, and they are the only Indians that hunt in this section of the mountains. For years, from their reserve, south to Chief Mountain, they have systematically driven the valleys and hills and slaughtered the game. ... In season and out, winter and summer, in lambing and fawning time, in fact as long as any game is in sight, they shoot. There is no stop; no rest for the hunted beasts. The old haunts are deserted and sheep runs are falling into disuse, and the greatest game country the sun ever shone on is fast becoming a thing of the past."4

The enlarged Rocky Mountains Park now incorporated much of the eastern slope of the Rockies. It took the form of a huge triangle having a northern boundary 90 miles in length, and tapered southerly to a point where Range 8, west of the 5th meridian, intersects the continental divide. It included a substantial portion of the game-denuded area for which Douglas had expressed concern. Effective control of the wildlife, including its protection, appears to have been impossible until 1909, when the first year round park warden service was established. This development is described later in this volume.

A Park Museum

During the early days of Rocky Mountains Park, the Department of the Interior employed various means of attracting visitors to the park and fostering interest in wildlife conservation. In 1895, a small museum was opened on a site south of the Bow River bridge and east of the Sanitarium Hotel. The building originally had been planned as a residence for the park superintendent, but during a visit to the park in 1890, the Minister of the Interior, Edgar Dewdney, indicated his interest in having it converted to the purposes of a park museum. Completion of the building was delayed for a few years, but in 1894 it was removed from its original location near the Banff Springs Hotel and re-sited on Villa Lot 1 in Block 2. It was opened for public use in July, 1895, and the exhibits, carefully assembled by the curator, Norman Sanson, gradually attracted an increasing number of visitors.

In 1903, the museum was moved to a new building on Banff Avenue which also provided accommodation for the park superintendent and his staff. The museum occupied space on the second storey, and its exhibits included well mounted specimens of larger mammals found in the park, together with mounted birds and waterfowl, and examples of rocks and minerals. Among the most striking exhibits were specimens of mountain sheep and mountain goat, elk, deer and buffalo.

The building, now a landmark in Banff, continues to provide a home for the museum. After a new park administration building was constructed and occupied in 1936, some of the space vacated by the park superintendent and his staff was made available to permit a more advantageous display of the museum's exhibits. Over the years, these have undergone periodical review and rearrangement during which outworn or superfluous items have been discarded or donated to other institutions, thus effecting a more selective and representative display.

Park Buffalo Herd

The role of Canada's national parks as sanctuaries for endangered species of wild life took form in 1897. In October of that year, the department received as a gift from a public-spirited citizen of Toronto, T.G. Blackstock, Q.C., three buffalo for display at Banff. This donation, which arrived from Texas, seems to have been unexpected. Superintendent Douglas had to provide make-shift accommodation for the bull and two cow buffalo in the former grounds of the Royal North West Mounted Police, which he enclosed with a strong fence. Some of the former police buildings, of log construction, were used for shelter, and a supply of hay was purchased for forage.

In June, 1898, this gift was supplemented by 13 head of buffalo from a small private herd maintained near Winnipeg by Lord Strathcona, one of the founders of the Canadian Pacific Railway. These animals had an interesting pedigree. In 1873, C.V. Alloway of Winnipeg and Hon. James MacKay, speaker of the Manitoba Legislature, joined a brigade of half-breed buffalo hunters and captured three buffalo calves southwest of Battleford, N.W.T. Two more calves were captured in 1874, near the International Boundary, and the five young buffalo were raised to maturity with the assistance of a domestic cow. By 1878, the small herd numbered 13 pure-bred and three cross-bred buffalo. MacKay died that year and Alloway sold the herd to Col. S.L. Bedson, warden of Stony Mountain penitentiary, for $1,000.5

Lord Strathcona is believed to have financed the deal, and nine years later received 27 buffalo in payment. Bedson sold the balance of his herd, 100 head, to C.J. "Buffalo" Jones of Garden City, Kansas.

Lord Strathcona's buffalo were maintained on an estate at Silver Heights near Winnipeg. In 1898, he disposed of the greater part of his small herd. Five head were donated to the City of Winnipeg, and 13 to the Government of Canada for its national park at Banff. Superintendent Douglas had been notified in November, 1897 of the proposed donation, and on their arrival at Banff, the buffalo were installed in a paddock located about a mile and a half east of the station. The paddock, consisting of about 500 acres, had been fenced earlier in the year, and contained adequate summer pasture and water. Winter shelter was provided by the construction of semi-enclosed sheds, and hay was purchased to supplement available forage. In 1904, Superintendent Douglas negotiated an exchange of two buffalo bulls from the herd at Banff for two from a herd owned by Austin Corbin of Newport, New Hampshire. Corbin's small herd had been developed from buffalo obtained from "Buffalo" Jones.

Under careful supervision, the buffalo at Banff gradually increased in numbers until it consisted of 107 head in March, 1909. In 1900, Douglas had placed five elk and 12 antelope in the buffalo paddock. The elk, later augmented by a few deer and moose, increased slowly, but the antelope experiment was a failure. The pronghorn antelope is a fleet creature of the western plains, and rarely thrives in any state of confinement.

Demise of Sir Donald

In his annual report for 1909, Parks Commissioner Douglas reported the death early in March of Sir Donald, the patriarch of the Banff buffalo herd. Apparently, he had been attacked by younger bulls, knocked off his feet, and gored and trampled almost beyond recognition. A large handsome bull, Sir Donald was believed to be one of the last specimens of the buffalo that had roamed the Canadian prairies in a wild state. He was one of the calves captured in 1873 by C.V. Alloway and James McKay, and later sold to S.L. Bedson. When Lord Strathcona started his small herd at Silver Heights, Manitoba, Sir Donald was one of 27 buffalo obtained from Bedson. In 1898, he was among those shipped from Silver Heights to Banff.

In reporting the incident, Commissioner Douglas explained that it had been the intention to extend special care to Sir Donald and preserve his life as long as possible as a matter of scientific interest, with a view of determining the longevity of the species. However, Sir Donald had probably by reason of age, been relegated to the status of an "outcast" bull, and his presence in the limited area of the paddock had inspired an attack from his younger rivals which he was unable to repel. Although the carcass was disfigured to an extent that forbad mounting, his head was preserved and mounted for posterity. The old bull buffalo was believed to have attained the age of 37 prior to his death. As Douglas concluded his report of the incident, ". . . His history during his 37 years of captivity had been one of romantic interest to thousands of people as the sole survivor of a noble type of animal, that in its wild state has become only a memory to the Indians, buffalo-hunters and oldtime white pioneers".6

When Howard Douglas made arrangements for the mounting of Sir Donald's head, he probably hoped that it would be preserved in perpetuity. The first destination of the mounted head was Government House, Ottawa, where it was on display for many years. In October, 1926, the Commissioner of National Parks wrote to the Controller, Government House, offering to furnish a newly mounted buffalo head in exchange for "one with a broken horn but of considerable historic interest" which was in his custody. The offer was accepted, the exchange made, and records indicate that Lord Willingdon, the Governor General, was "delighted".

On its return in December, 1926, Sir Donald's damaged head was held in the commissioner's office for several months, and then was presented to the National Museum of Canada. There it remained until February, 1942, when, owing to its fragile condition, it was dismounted. The entire skull, however was retained and, now more than 100 years old, it forms an interesting link with early days on the Canadian prairie.

The Banff Zoo

Another development undertaken by Superintendent Douglas at Banff during the early part of the 20th century was the creation of a zoo. Although this project could hardly be termed a conservation measure — since many of the early exhibits constituted exotic rather than native wildlife — it proved to be an outstanding visitor attraction throughout the years of its existence. In 1901, Douglas began to supplement species in the animal paddock east of the town with other animal and bird specimens. By 1904, these included several Persian sheep, three coyotes, a timber wolf, two cougars, a badger and two golden eagles.

Funds were made available in 1905 for the construction of a large rustic structure or aviary on the grounds at the rear of the Banff museum for the accommodation of birds.

Into this building, which contained nine cages or compartments, Douglas introduced two pairs of Japanese pheasants, the gift of William Whyte, a vice-president of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. To these were added seven pairs of other varieties of pheasant, a very handsome gamebird. In 1906, a new cage for two golden eagles was added, and that year all birds in the animal paddock were relocated in the aviary.

During 1907, the construction of additional cages for the accommodation of the smaller mammals in the paddock was undertaken, and by March 31, 1908, their transfer to the combined aviary and zoo on the museum grounds had been completed. The cages were modern and sanitary in design, having been constructed of iron, concrete and limestone rock. Each cage was supplied with water and sewer connections which permitted a constant flow of water through each unit.

On its inception, the new zoo contained, in addition to a number of birds, three specimens of the black bear family — black, brown and cinnamon; two mountain lions or cougars; three timber wolves; two coyotes; kit and red foxes; and specimens of lynx, raccoon, badger, marmot and porcupine. In 1911, Superintendent MacDonald obtained two grizzly bear cubs for the zoo, and in 1912, a polar bear cub in exchange for two moose from the paddock. A special cage, equipped with a plunge pool, was built for the polar bear, which remained an outstanding favourite with visitors for the next 25 years.

The zoo population varied throughout succeeding years, and probably reached its zenith in 1914 when it contained 50 mammals and 36 birds. Although losses in some species were replaced when possible, a decline in the number of caged birds was noticeable by 1935. Of the 24 birds in pens or cages, 12 were Canada geese. In 1937, the National Park administration at Ottawa decided the Banff zoo was no longer a desirable park feature. A number of animals in cages such as bear, Rocky Mountain sheep and mountain goat normally could be seen along many park highways and trails. Moreover, the spectacle of native wild mammal and bird species being maintained in captivity within a national park — itself a museum of nature — appeared both inconsistent and anomalous.

Consequently, the zoo was discontinued at the close of the 1937 visitor season, and the mammals and birds were either liberated or donated to other zoos.7 The Calgary zoo was the recipient of one of the prized exhibits — the polar bear, together with the four-horned sheep, yak, timber wolves, coyotes and several other species. Donations were also made to zoological gardens at Quebec City, Toronto, Winnipeg and Rome, Italy. The cages, ponds and stone animal dens were dismantled and the site cleared. The former attraction was replaced in 1939 by a picnic area and playground for day visitors. A large parking area for automobiles also was constructed adjoining Buffalo Street.

The disappearance of the zoo brought some protests from the citizens of Banff, particularly from "old-timers" who had witnessed its development. In general, however, both residents and visitors accepted the concept that Banff National Park, containing an area of more than 2,500 square miles, offered adequate opportunity for viewing numerous wildlife species in their natural surroundings.

Game Fish Propagation

Of the numerous recommendations contained in the 1886 report of W.F. Whitcher for the development of Banff National Park, probably the last to be implemented was the construction of a fish hatchery at Banff. This action, long overdue, had been urged consistently by former Superintendent Howard Douglas. Little stocking of streams in the park had been done, and most of what was accomplished had been carried on by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. One notable distribution was the deposit in 1904 of 800 adult Nipigon brook trout in the Bow River west of Banff Townsite.

The Banff Hatchery

The Banff fish hatchery was erected in 1913 by the Department of Marine and Fisheries, which also carried on its operation for the next 18 years. Located in a small park between Glen and River avenues near Bow Falls, the two-storey building was fitted out with 30 hatching troughs in clusters of five. During its first year of operation, one million lake (salmon) trout fry were produced and most of these were distributed in Lake Minnewanka.8 Two large outdoor ponds constructed on the hatchery grounds in 1914 functioned as rearing pools during the summer season. The establishment was complemented by a dwelling occupied by the hatchery superintendent. The hatchery and pools formed an outstanding visitor attraction for many years, until it was found necessary to discontinue their operation.

In 1931, the management of the Banff hatchery was turned over to the Department of the Interior, and the hatchery staff subsequently carried on their duties under the park superintendent. An extensive program of restocking waters in the mountain national parks was carried on, using rainbow, cutthroat, brook trout and lake trout. Although 154,000 Atlantic salmon fry were introduced to Lake Minnewanka in 1919, lake trout continued to provide the principal catch in this popular lake. The Cascade River system, however, was stocked in 1959 and 1960 with eyed eggs of Atlantic salmon imported from eastern Canada.

Normal operation of the Banff hatchery was disrupted in 1947, following the chlorination of the town's water supply. The chemically-treated water had a disastrous effect on the fish fry, and after unsuccessful attempts had been made to carry on fish culture by using sulphur water from the Banff mineral springs, and filtered water from Bow River, the original hatchery was closed in 1956. Fish culture operations then were transferred to a small building at Duthill east of the townsite, and some auxiliary hatching troughs were set up below Johnston Lake at Anthracite. Later, in 1960, when the fish culture activity of rearing rainbow, brook and lake trout in the mountain national parks was consolidated at the Maligne River hatchery in Jasper National Park, the Duthill hatchery operation in Banff Park was reduced to an annual three-month operation for rearing cutthroat trout only. Operations at this site were continued on a seasonal basis until 1969, when the facility was closed permanently.

Development of Splake

Despite the difficulties experienced by the fish hatchery staff at Banff with the water supply, an experiment undertaken by Park Warden J.E. "Ernie" Stenton of the Minnewanka Warden District resulted in the development of a hybrid trout. Warden Stenton's artificial cross was first attempted in 1946, utilizing lake trout and eastern brook trout. Although exposure to chlorinated water resulted in the death of the eggs before complete development, the cross was successfully completed by Warden Stenton during the following year. Later, crosses made by members of both the Banff and Jasper park hatchery staffs were successful, and offspring obtained.9

The cross between female lake trout and male brook trout was successful with low mortality during incubation. Strangely, a reverse cross between female brook trout and male lake trout resulted in heavy losses and deformed fish. The hybrid fish resulting from the successful crosses was designated as 'splake' trout by the biologists of the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests, and as 'moulac' by those of the Quebec Department of Fish and Game. Later, a third name, 'Wendigo', was given to the hybrid following publication of a photo of the hybrid in the magazine Forest and Outdoors.

A shipment of the hybrid trout eggs was made to the Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory at Maple, Ontario in 1950. Later crosses of trout were carried on by biologists of both the Ontario and Quebec Governments, and by the Wyoming Fish and Game Commission. Plantings of hybrid trout were made in a number of lakes in Banff and Jasper National Parks and after planting, the growth of the hybrid fish was reported to be most satisfactory.

In general appearance, the adult hybrid is midway between the lake and brook trout. The body is not as slender as the lake trout, the tail is forked, and the profile of the head is that of the lake trout. Colouration is variable. The back is usually vermiculated like the brook trout, fins sometimes are banded with white, and the belly is white.

Eventually the planting of splake in park waters was discontinued, particularly after water supply problems prompted the temporary termination of hatchery propagation of fish stocks and the purchase of fry from sources outside the parks.

Operations at Waterton Lakes

Sport fishing in Waterton Lakes National Park was vastly improved and extended following the decision of the Department of Marine and Fisheries in 1927 to erect and operate a fish hatchery there. Since the days of Kootenai Brown, the first settler on land now contained in the park, Upper Waterton Lake had yielded good catches of lake trout. The potential for sport fishing in other park waters, however, had not been exploited. Prior to the advent of the hatchery, the park superintendent relied on the Banff hatchery for most of the fry introduced to the lakes and streams of the park. Donations also were received for several years from a hatchery operated by the United States National Park Service in Glacier National Park, Montana.

The Waterton Lakes fish hatchery was built on a site adjoining the Pincher Creek entrance road about six miles north of Waterton Park townsite. It was served by a good supply of spring water. Completed in 1927, the hatchery was complemented by a dwelling built for the use of the hatchery superintendent, and a combined garage and workshop.10. According to park records, the total outlay for the hatchery and accessory buildings was $8,500. Fry and adult fish reared at the hatchery were distributed not only within the park but also in provincial waters throughout southern Alberta, which received the major share.

In 1931, the operation of the hatchery was transferred by the Department of Marine and Fisheries to the Department of the Interior, and subsequently the rearing facilities were enlarged. In 1937, construction of a group of rearing ponds was undertaken by the park superintendent on a site in Block 35 of the townsite, just south of Cameron Falls. The ponds, together with a supervisor's cabin, were completed and opened for use in the summer of 1938.

The Waterton Lakes hatchery was used until 1960, when the consolidation of fish hatchery operations with those at Jasper Park was effected. Although the hatchery buildings were converted to other uses, the rearing ponds were retained for a few years for holding parent fish stocks which were captured for egg collection purposes. After the fish were spawned, they were returned to the lakes from which they were taken. The townsite ponds also were retained, although in later years they functioned mainly for display purposes and as retention areas for fish intended for planting.

A program of stocking or restocking streams and lakes in the park which was carried on after the opening of the hatchery, provided visitors with excellent opportunities for angling. The most widely distributed varieties of fish were rainbow, cutthroat and brook trout. A number of small lakes at high altitude such as Crypt, Lone and Lost Lakes, Lineham Lakes and Rowe Lakes, were stocked primarily with rainbow and cutthroat trout. Although difficult of access, they usually rewarded the angler for his effort. The main Waterton Lakes, one of which has a maximum depth of 405 feet, for many years offered exceptional trolling for lake trout. The largest game fish recorded by an angler in the park was taken from Upper Waterton Lake in July, 1920, by Mrs. C. Hunter of Lethbridge. It was a lake trout weighing 51 pounds.11

Fish Culture at Jasper

Although Jasper was the largest of the Rocky Mountain national parks, opportunities for sport fishing in its waters during the early 1920's were poor. Many of its lakes and streams were barren of fish, and a growing tourist industry, stimulated by the construction of Jasper Park Lodge, indicated the need for an extensive fish-stocking program. With the assistance of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, the Commissioner of Parks arranged for an investigation of park waters by the Biological Board of Canada. Studies were carried out by a group of scientists from the University of Manitoba in 1925 and 1926 to determine the volume and variety of natural food available for the propagation of fish, as well as the most suitable species that various waters would sustain. Areas investigated included the Maligne-Medicine lake system, and also lakes and streams in the vicinity of Jasper Townsite, in the Yellowhead Pass area, and in the upper Athabasca River Valley.

The recommendations of the investigators, who included Dr. A. Bajkov, Ferris Neave, A. Mozley and Miss R. Bere, later were implemented. Small aquatic plants were placed in several lakes in the vicinity of Jasper Park Lodge in 1927. Brown trout fry also were distributed in Mildred, Edith, Annette and Big Trefoil lakes, by officers of the Banff hatchery. These lakes then were closed to fishing for two years to facilitate the growth of fish.12

The stocking of Maligne and Medicine lakes, and the connecting Maligne River, had been strongly recommended by the Biological Board of Canada. However, the task of transporting fry from the Banff hatchery to Jasper, and from there to Maligne Lake over a rough mountain trail presented a formidable obstacle to the proposed program. After an on-the-ground review of the problem by the park superintendent and the dominion inspector of fisheries of Alberta, it was decided to convert a vacant construction cabin in the vicinity of the townsite water reservoir near Cabin Lake into a temporary hatchery.13 This temporary facility at the townsite reservoir was closed down sometime in the early 1930's. Concurrently, the hatchery operation was moved to the basement of the park administration building, and continued at this site until a new hatchery at Maligne River was brought into service.

Another decision made was the selection of eastern brook trout — an exotic species — for introduction in the Maligne River system. During the winter of 1927-28, 250,000 brook trout eggs were obtained from a commercial hatchery at Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. In July, 1928, 190,000 fry were transported by pack-horse to Maligne Lake. Of these, 178,000 were placed in Maligne Lake, and the balance in a creek linking Beaver Lake with Medicine Lake. A second planting of 208,000 fry was made in 1929 and a final planting of 179,000 fry in 1931.14

Spectacular Success

The stocking of the previously-barren Maligne River system with brook trout was very successful. The fish grew rapidly. In September, 1929, 16 months after planting, some trout specimens taken for observation were reported to measure from 14 to 18 inches in length and to weigh from one and one-half to two pounds. In September, 1931, fish four pounds in weight were taken and in December that year, one of six pounds was captured. Maligne Lake and tributary waters were opened for fishing on June 1, 1932, and many anglers had little difficulty in obtaining their daily limit — then 15 fish — in Maligne and Beaver lakes. In 1932, catches continued to be heavy, and consequently the daily limit was reduced in 1933 to 10 fish per day with a season limit of 200 pounds.

Maligne Lake, 14 miles in length, not only was the largest glacial-fed lake in the Canadian Rockies, but also one of the most scenically spectacular areas in Jasper Park. Published reports of the successful introduction of trout in a previously-barren lake induced very heavy fishing, and during the seasons of 1933, 1934 and 1935, 5,616 trout having an average weight of 23 ounces were taken by anglers. From 1936 to 1940, both the numbers of fish caught and the average weight declined. Although the average weight levelled off to between one and two pounds, Dean Tweedle of Jasper caught a 10-1/2 pound trout in Beaver lake in 1943. The disparity of early and late catches was explained by the Director of Fish Culture, Department of Fisheries as follows:

"The system has apparently gone through the usual phases that occur when barren lakes are stocked and it would seem reasonable to assume that the system is now producing its normal weight of fish in relation to the crops of natural fish food that it produces annually. In other words, the annual crops of fish have reached a normal level".15

Other Waters Stocked

Following the completion of additional biological studies of lakes and streams in Jasper Park, the program of stocking various waters with suitable species of fish was accelerated. By 1940, the limitations of the park fish-rearing facilities were realized, and in 1941, construction of a hatchery was commenced on the Maligne River about half a mile above its junction with the Athabasca River. The new building was completed in 1942, and placed in charge of a hatchery superintendent, William Cable. In 1947, a residence for the use of the hatchery superintendent was erected, and in 1948 a utility building incorporating staff quarters was added to the hatchery complex. The original development included a group of 10 outdoor circular rearing ponds and four rectangular ponds. In the early 1950's, an auxiliary facility was established at the townsite water reservoir near Cabin Lake. The building was used as a sub-hatchery each year from June to September until 1962, when it was dismantled and re-erected at the Maligne River hatchery site.

In 1959, a new source of water supply for the hatchery was brought into use. It came from springs located on the east side of Maligne River, and the water was conveyed to the hatchery by pipe. The use of water from the river was continued, except during brief periods when it was heavily laden with silt. Other improvements made at the hatchery were the installation of concrete raceways, and the construction of a brood pond.

Parks Fisheries Investigations

Before 1940, when the first limnologist was appointed to the Wildlife Division of National Parks Branch, scientific advice on fisheries management was provided by officers of the Biological Board of Canada, the Department of Fisheries, or by private consultants. Mainly, they were concerned with having park waters stocked with suitable varieties of game fish, or alternatively, the removal from park lakes and streams of coarse or objectionable species of non-game fish. Prominent among the early consultants was Dr. Donald Rawson of the Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon. Dr. Rawson pioneered game fish studies in Prince Albert and Riding Mountain national parks, and over a period of nearly 15 years, also carried on consultant duties in the Rocky Mountain national parks.

The first national park limnologist, Dr. Harold Rogers, served for a little over a year before he enlisted in Canada's armed forces, and lost his life in war service overseas. He was succeeded in 1945 as limnologist by Dr. V.E.F. Solman. The promotion of Dr. Solman in 1949 to chief biologist in the Wildlife Division led to the appointment as limnologist of Jean-Paul Cuerrier, formerly associate professor of biology at the University of Montreal. Cuerrier subsequently provided consultant services for the national park limnological program for the ensuing 25 years, as chief limnologist in the Wildlife Division and later in the Canadian Wildlife Service. In 1951, J. Clifford Ward, limnologist of the Canadian Wildlife Service was appointed district fishery biologist for the western national parks, with headquarters at Banff, Alberta. When eastern and western regions of the Canadian Wildlife Service were created in 1962, Ward's headquarters were transferred to Edmonton. During his term of office, Ward was called upon for technical advice on many problems associated with game fish management including those at park fish hatcheries.

Angling Pressures Develop

Prior to and following Great War II, the federal and provincial governments, as well as the two Canadian Railway companies, gave considerable prominence in their promotional advertising to game fishing opportunities in Canada. The success attending the stocking of the Maligne-Medicine Lake system in Jasper park had helped focus attention on the national parks game fish possibilities, and gradually park authorities were under pressure to increase the fish population in national park waters. Fish and game associations also became active in calling attention to what they believed to be deficiencies in programs that would satisfy the ever increasing numbers of anglers.

Superintendents of the national parks in western Canada relied mainly on the production of the three hatcheries at Banff, Jasper and Waterton Lakes parks for fry and fingerlings utilized in the annual stocking operations. These supplies were supplemented by donations from provincial sources, mainly on an exchange basis. The lack of a suitable supply of water forced the closure of the main Banff hatchery in 1956, and the Waterton hatchery had a limited capacity. In 1954, Jean-Paul Cuerrier, chief limnologist of the Canadian Wildlife Service, was requested to undertake a review of all hatchery operations in the mountain parks in order to assess their productive capacity. Following his investigation, Cuerrier recommended that the Waterton Park hatchery be abandoned for fish culture purposes, and that the townsite ponds be retained during the summer months for display purposes and for holding fish intended for distribution in local waters. He also recommended that the Banff hatchery be reduced to a six-month operation each year using existing facilities for display and rearing purposes under supervision of the district fisheries biologist.16 His most drastic recommendation involved the recognition of the Jasper Park hatchery as the main establishment supplying the mountain parks with fish. An expansion of the existing Jasper hatchery was urged, together with the provision of an additional water supply during the annual run of silt in the Maligne River. An additional study completed by Cuerrier in 1955 reviewed the costs of operation of the three park hatcheries involved, and the estimated cost of operating a single hatchery at which all fish culture operations might be concentrated.

Central Hatchery Designated

Action on these reports was deferred while the various recommendations were exhaustively discussed both at Ottawa and in the field. Eventually, a consensus favoured a solution that would solve fish rearing problems and reduce staff and expenditures by concentrating all future activities at the Jasper Park hatchery. In February, 1960, chief limnologist Jean-Paul Cuerrier recommended by memorandum to the Chief, National Park Service, that (1) the Waterton Lakes Park hatchery be closed, although retaining the display ponds at Cameron Falls; (2) that the Banff Park operations be confined to retention of the limited troughs at Duthill for the part-time rearing of trout; and (3) that the main hatchery operations be concentrated at the Jasper Park hatchery. A few days later, these recommendations were forwarded to the deputy minister for consideration and approval, with the advice that water supply was a main factor and that only at Jasper could a satisfactory flow be obtained.17 Departmental approval for the new plan of operation was granted, effective May 1, 1960.

Consolidated Program Begun

Following the consolidation of national park fish rearing operations in the summer of 1960, the Jasper Park hatchery embarked on the task of supplying trout fry and fingerlings for all national parks in Alberta, British Columbia, and Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba. A.C. Colbeck, officer in charge of the Waterton Lakes Park hatchery, was transferred to Jasper to supervise the consolidated fish culture operations at the hatchery there. Assistance was received from the park warden service in collecting fish eggs from various park waters for incubation. The balance of requirements was obtained from sources outside the parks, including hatcheries operated by provincial and federal governments and by private enterprise. During the year 1962, more than 66,000 fingerlings were distributed in Jasper National Park and approximately 400,000 more in five other western national parks.18

Losses from Diseases

The rearing of fish from eggs to fingerlings or even to adults is a delicate operation. The temperature and clarity of available water are important factors in hatchery operations as are diet and the risk or presence of viral or bacterial infection. Contamination of water resulting from the use of insect or pest controls such as DDT is also possible. Mortality in hatcheries is also known to have been caused by dissolved copper and zinc from pipes and valves. Losses in national park hatcheries also have occurred from ailments such as "cold-water", "gill", and "kidney" diseases, and from infectious pancreatic necrosis, better known as IPN.

In November, 1955, the officer in charge of the Waterton Lake Park hatchery reported to the park superintendent that heavy mortality had been experienced in the rearing of rainbow and cutthroat trout.19 Early symptoms had included loss of appetite, extended gill covers and twirling, before ending belly up on the bottom of the trough. Specimens were submitted to the microbiological laboratory of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service at Kearneysville, Virginia, for examination. In December, 1955, the park superintendent received a report from the microbiologist, Dr. K.E. Wolf, that the fish were suspected of having died from acute pancreatic necrosis, a new description for a disease previously described as acute catarrhal enteritis. Both the cause and control of the disease were then reported to be unknown.20 Later in October, 1964, Dr. Wolf confirmed the diagnosis of 1955, and stated that the infection then known by its earlier name had been reported in 1940 from the "Maritime provinces of Canada".21

Rearing Problems at Jasper

By the early 1960's, large quantities of fish eggs were being obtained from federal government fish hatcheries in causing concern. After bacteriological and virological examinations of some of the affected hatchery-reared trout were made, the losses were attributed to a viral disease, infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN). That year, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development entered into a contract with a consultant in Seattle, Washington — Kramer, Chin and Mayo — for a study of the Maligne River trout hatchery, which it was hoped would determine deficiencies in its operation and develop a long range plan for its improvement. The consultant's report, submitted later that year, found the hatchery water supply inadequate in quality and the hatchery obsolete. The report also recommended that a new hatchery be constructed and that the existing hatchery, after improvement, be used as a visitor facility.22

In April, 1972, further study of fish diseases at the Jasper Park hatchery was undertaken by Dr. T. Yamamoto of the Department of Microbiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, in association with A.H. Kooyman, limnologist of the Canadian Wildlife Service and D. Valin, superintendent of the hatchery. Dr. Yamamoto's report, completed in November, 1972, also confirmed that a high incidence of IPN existed in all adult, two-year-old, and yearling brook trout stocks. It also confirmed the presence of other diseases, including gill and kidney maladies. The report recommended the development of a new hatchery, dependent on the availability of a sufficient and sanitary supply of underground well water. Also disclosed was the fact that if an adequate supply of pure water could not be obtained, a continuation of disease problems at the Jasper hatchery could be expected.23

Also in 1972, a bacteriological examination of fish at the Jasper hatchery was undertaken by members of the Pacific Biological Station of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, located at Nanaimo, British Columbia. The examination also confirmed the presence of bacteriological kidney disease and IPN at the hatchery. The examining officers, G.R. Bell, T.P.T. Evelyn and G.E. Hoskins, recommended that the hatchery be placed under quarantine until a firm policy respecting its future operation was reached. They also suggested that consideration be given to the elimination of the hatchery and the purchase of certified stocks of fish eggs from other sources.24

Early action followed the receipt of this report. The hatchery was placed under quarantine in September, 1972, and a large number of diseased fish were destroyed. The hatchery grounds also were closed to visitors. During the autumn of 1972 and spring of 1973, the hatchery and grounds were disinfected in an effort to eradicate IPN. However, in May, 1973, the presence of IPN again was detected in a group of 5,600 two-year-old rainbow trout which had been free of disease in 1972. These fish also were destroyed. The remaining stock of rainbow trout found free of disease were utilized in stocking park waters.25

Hatchery is Closed

Following consideration of various factors disclosed by investigational reports, and bearing in mind the cost of replacing the existing hatchery establishment, the permanent closing of the Jasper Park hatchery, effective June 30, 1973, was announced by the Director, Western Region of Parks Canada at Calgary, Alberta. The press release confirming the decision stated that discontinuation of the hatchery was due to the obsolescence of the existing plant and the presence of fish diseases. It also was disclosed that other sources for continuing the stocking of park waters at a desirable level were available.

The decision to close the park hatchery was followed by protests from anglers and other groups. A formal protest by the Jasper Park Chamber of Commerce and the local fish and game association resulted in a meeting of representatives of these groups with senior officers of the Western Region, Parks Canada, and limnologists of the Canadian Wildlife Service. The problems experienced by the park hatchery staffs in trying to provide adequate fish stocks over a ten-year period were reviewed, and future park policy respecting the stocking of park waters with game fish was explained. It was revealed that the incidence of disease in the hatchery could be attributed to the purchase of trout eggs from eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. These purchases had been made to produce fish for stocking purposes, in the light of an ever-increasing demand for better sport-fishing in the national parks.

Public concern and that of national park administrators about impairment of the aquatic environment necessitated a change in management procedures and guide lines respecting sport fishing in the national parks. To correct these conditions, sport fishing has been maintained and managed since 1973 in waters designated for fishing by (a) reliance on wild self-sustaining populations of fish through natural reproduction at the individual lake productivity level, and (b) by stocking waters where game fish already existed and such waters would support a fishery without seriously disturbing the natural balance or causing undue impairment of park values.26

The decision to discontinue the propagation of game fish in national park hatcheries probably was logical. However, it evoked feelings of regret not only among the perennial anglers, but also among park officers and technicians who, over the years, had produced millions of fish fry and fingerlings. Many had been retired, and those remaining had been assigned to other duties. They will no doubt recall with nostalgia, the unfailing services of their associates, including hatchery superintendents Jack Martin, Gerry Bailey, Art Colbeck and Bill Cable. Also to be remembered were the technicians, among whom were Ken Goble, Bob Capel, Jim Stringer and Joe Kilistoff. Not forgotten either, were members of the park warden service who transported live fish stocks up the valleys, over the hills, and across the lakes to their final destinations.

Meanwhile, resource conservation policy will continue to be reviewed with the object of ensuring that sport fishing may continue to be part of a "park experience" for visitors in years to come.

Preserving the Buffalo

One of the most ambitious experiments in wildlife conservation ever undertaken in Canada involved the purchase by the Department of the Interior, of the largest herd of buffalo remaining in private ownership on the North American continent. The object of this investment was to ensure the perpetuation of a species which had once ranged over much of western Canada and the United States in millions, only to be reduced by hunting almost to the point of extinction.

The American bison, better known as the buffalo, had the distinction of being the largest and most abundant big game animal on the continent. Its amazing size, enormous head, and splendid chest and shoulders covered with a magnificent coat of shaggy brown hair, combined to provide a description by a well known naturalist as "the grandest ruminant that ever trod the earth". During the period in which exploration of the North American continent began, no other large game species exceeded it in numbers, and few have equalled it in value to mankind. It provided the native Indian tribes and early settlers with food, clothing and materials for shelter. Its meat was nutritious and well-flavoured; its thick robe was valued for protection against bitter cold; its hide was used for tepees and boats; and even its hair, horns and hoofs were used for various articles of personal use and adornment.

When exploration and settlement of the great central plains of North America began, the buffalo population was incredibly large. It roamed in great herds, some of which were recorded as moving forward on a front of not less than two miles in width and 25 miles in depth.27 Its range, according to Dr. W.T. Hornaday, an authority on the species, extended from tidewater on the Atlantic coast westward across the Allegheny Mountains to the prairies along the Mississippi River and southward to the delta of that great stream. The buffalo also were found west of the Rocky Mountains in New Mexico, Utah and Idaho, and northeast of the Rockies to Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories.

Slaughter followed Settlement

The buffalo provided the Indian tribes of the great western plains of America with much of their subsistence, and although these aborigines showed little inclination to abstain from killing more animals than actually were needed, their destruction had, for many years, little effect on the annual increase of the herds. However, following the opening up of the American west by railway construction and the arrival of settlers and others who brought more efficient weapons, a disastrous inroad on the species began. By 1820, systematic slaughter of the buffalo was under way. A commercial demand for buffalo robes made the hunting of buffalo a lucrative undertaking, and many adopted it as a means of livelihood. Organized expeditions numbering hundreds of hunters accounted for an increasing number of animals killed. By 1840, buffalo were very scarce in the vicinity of the Red River settlement, where settlers and Indians had virtually extinguished the formerly numerous buffalo. The construction of the Union Pacific Railway between 1865 and 1869 divided the buffalo in the United States into two great herds — northern and southern. Easier access to the great plains area brought additional hunters, and the slaughter of the buffalo reached its peak in 1873. By the end of the following year, the extinction of the southern herd had virtually been completed. Hornaday estimated that 3,158,730 buffalo were killed by hunters in the three-year period of 1872-1874.28

Concurrently, the slaughter of the northern herd, whose range extended northerly from the Platte River into Canada, was hastened by the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway. The rails of this line were laid to Bismarck, Dakota, in 1876, and from that date onward it received for transportation to eastern markets, all the buffalo robes and hides that came down the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. Most of the wild herds, other than scattered bands had disappeared from western Canada by 1879, and consequently, the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway across the prairies during 1882 and 1883 had no effect on the buffalo population.29 The Metis or half-breeds of Manitoba, the Plains Crees of Qu'Appelle, and the Blackfeet of the South Saskatchewan country had swept bare of buffalo, the great belt stretching from Manitoba to the Rocky Mountains. By the end of the 19th century, the only wild buffalo remaining in any quantity in Canada comprised the small herd of "wood bison", a sub-species of the plains bison, which occupied a range in the Northwest Territories bounded by the Slave, Peace and Hay rivers, and the southern shores of Great Slave Lake. These animals enjoyed police protection under Canadian law after 1890, and in 1922 much of their range was incorporated in a national park.

The eventual disappearance of such a large grazing animal dependent on vast grazing areas was inevitable. History has confirmed that the indigenous game of any country must disappear or suffer drastic reductions with the advance of settlement. In western North America, the feeding grounds of the buffalo were supplanted by farms, ranches, towns and even cities. To later generations, made more sensitive to the loss of native wildlife by modern conservation practices and education, the rapid and reckless destruction of such a magnificent mammal seemed lamentable. No doubt the public conscience, in the closing years of the 19th century, influenced the development of small exhibition herds of buffalo from surviving specimens, including that established at Banff in 1897.

Privately-owned Herds

By 1900, the buffalo population in North America had reached its lowest ebb. Two existing wild herds, one located northwest of Lake Athabasca in the Northwest Territories of Canada, and the other in Yellowstone National Park, Montana, had quasi-legal protection.

A number of privately-owned herds maintained in captivity or semi-captivity had been developed by ranchers and others, and these in future would form a nucleus for the preservation of the species. Mention has been made earlier in this chapter of the herd developed at Stony Mountain, Manitoba, by S.L. Bedson. Other privately-owned herds of the period were those owned by the Canadian Department of the Interior at Banff in Rocky Mountains Park; by Colonel Charles Goodnight in Texas; by C.J. "Buffalo" Jones at Garden City, Kansas; and by Arthur Corbin of the Blue Mountain Forest Park near Newport, New Hampshire. Other small herds included the W.C. Whitney herd near Lenox, Massachusetts, and the Trexler herd near Allentown, Pennsylvania.30

The Pablo-Allard Herd

The largest privately-owned buffalo herd in the United States — believed to contain 300 head — was owned by Michel Pablo of Ronan, Montana. The origin of this herd provides an interesting story. In 1873, a Pend d'Oreille Indian known as Walking Coyote, was fortunate in capturing four buffalo calves — two bulls and two heifers. Accompanied by his squaw and his stepson, the Indian had been wintering on the Milk River near the present site of Buffalo, Montana. During a hunting expedition, of which Walking Coyote was a member, the four calves were cut out of a large herd, and in accordance with a characteristic peculiar to the buffalo, the calves followed the horses of the hunters who had killed or separated them from their mothers.31

The following spring, Walking Coyote took his four buffalo calves to the St. Ignatius Mission, located in the centre of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Here the calves, by now tame, became pets and objects of interest at the mission. As the calves matured, they began to breed, and by 1884 the group had increased to 13 head. Walking Coyote found the cost of their maintenance beyond his means and he decided to dispose of them. Charles A. Allard, who was carrying on ranching operations on the reservation, learned of the proposed sale. Impressed with the possibility of developing a profitable venture in this group of almost extinct animals, Allard managed to interest a fellow rancher, Michel Pablo, in their purchase. The two formed a partnership and bought 10 of the buffalo for $2,500. Under careful supervision their herd increased, particularly after the infusion of 26 more pure-bred buffalo which were purchased from the "Buffalo" Jones herd in 1893 together with 18 hybrids. These buffalo were part of the group obtained by Jones from S.L. Bedson of Stony Mountain, Manitoba — also the source of the buffalo donated by Lord Strathcona to the Canadian Government for the exhibition herd at Banff.

The partnership was dissolved following the death of Allard in 1896. The buffalo herd, then numbering about 300 head, was divided equally between Michel Pablo and Allard's estate. The heirs sold their individual shares of the herd, and that of Mrs. Allard was purchased by Charles Conrad of Kalispell, Montana. Other buyers included Howard Eaton of Wolf, Wyoming, a noted hunter, who acquired the shares of the Misses Allard and their brother Charles, Jr. Later, Eaton's small herd was bought by Buffalo Jones for inclusion in a new herd established at Yellowstone National Park in 1902. Buffalo owned by Joseph Allard, the remaining heir, were purchased by Judge Woodrow of Missoula, Montana, and later were turned over to the 101 Ranch.

Pablo's Herd Threatened

Now the sole owner of a pure-bred herd of buffalo, Michel Pablo disposed of a number of his stock in small consignments shipped to various destinations. Many of his choicest specimens later were found in zoological gardens and private preserves in the eastern United States. Under ideal range conditions prevailing along the banks of the Pend d'Oreille River, his buffalo gradually increased. His hopes for a very large herd, however, were dashed when he learned in 1905 that his grazing privileges in the Flathead Reservation would be terminated shortly, when the land would be opened up for settlement.

Faced with the loss of his range, and with it the possibility of retaining his buffalo herd intact, Pablo sought help in disposing of his prized possessions. Howard Eaton tried unsuccessfully to influence the United States government in their purchase, and the recently formed American Bison Society was unable to help. Pablo visited Washington and aroused the interest of President "Teddy" Roosevelt, who recommended to the 60th Congress that the animals be purchased for a national herd, but failed to win support and an appropriation. Pablo is reported to have received an offer of $75 per head for his buffalo from a local speculator, but it was rejected.

Canadian Aid Sought

After his return from Washington late in 1905, Pablo was visited by Alexander Ayotte, an assistant immigration agent for Canada who was stationed at Great Falls, Montana. A native of St. Boniface, Manitoba, Ayotte had, on his appointment to a post south of the border, mastered Spanish and Indian dialects, and had become friendly with Pablo, a halfbreed of Mexican descent. Pablo explained his predicament to Ayotte. On his return to Great Falls, Ayotte brought the matter to the attention of J. Obed Smith, then Commissioner of Immigration at Winnipeg. On November 20, 1905, Smith wrote to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration at Ottawa as follows:

"I have been advised by Mr. Ayotte that during his travel in Montana in the interests of emigration, he met Michel Papleau (Pablo), whose post office address is Missoula, Montana, and he was told by Mr. Papleau that he was anxious to move his herd of buffalo, consisting of 360 head, from Montana to Western Canada. It occurred to me, however, that perhaps some of the Departments of Government are desirous of acquiring some of these animals for the Banff National Park, and as this appears to be a valuable herd and has been brought up in a district very similar to what we have in our own West, it affords an opportunity to secure a desirable bunch of these animals from the one owner."32

Scott sent a copy of Smith's letter to the Secretary of the Interior, P.D. Keyes, who in turn referred the matter to the Deputy Minister, W.W. Cory. Keyes' memorandum added the information that "the herd of buffalo now at Banff is as large as the Park can comfortably accommodate". The file indicates that the proposal was referred to the Minister, Frank Oliver, and on its return it bore a single word, "No"! On January 8, 1906, Cory advised Keyes that he had brought the matter to the Minister's attention and it had been decided that the government could not entertain the proposal. Smith was notified accordingly.

Pablo's need for assistance, however, was not allowed to remain unnoticed. On March 6, 1906, Benjamin Davies, the Canadian Emigration Agent at Great Falls, Montana, wrote directly to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration at Ottawa, stating that his assistant, Alex Ayotte, had been approached for assistance by Michel Pablo of Ronan, Montana. Pablo had explained that he was being forced to find a new pasture for his buffalo, as the Flathead Indian Reservation was being opened for settlement. Pablo wanted to know if the Canadian Government would grant him a grazing lease in southern Alberta and permit him to drive his herd across the international border, duty free. Davies concluded his letter with the information that "If the Government prefer to purchase the 300 head, he is open to sell at a reasonable figure."33

This communication was referred in turn to the Timber and Grazing Branch, the Forestry Branch, and the Deputy Minister of the Interior. Mr. Cory advised Mr. Scott on March 24 that

"I would be glad if you would find out from Mr. Davies at what figure Mr. Pablo would be willing to dispose of his buffalo to us."

Available records indicate a gap in the correspondence, but apparently on May 22, 1906, Howard Douglas, superintendent of Rocky Mountains (Banff) Park was instructed to proceed to Great Falls, contact Davies, and then inspect and report on Pablo's herd. Although not recorded in official reports to Ottawa, Howard Douglas consulted Norman Luxton, a Banff newspaper publisher, on the purchase of the Pablo buffalo herd. Luxton later accompanied Douglas to Montana where he witnessed the early round-up and shipment of part of the herd. In 1908, Luxton published a brief history of the Pablo buffalo, its purchase and shipment to Canada, in the illustrated booklet The Last of the Buffalo.

Douglas Reports on the Herd

On June 15, Douglas submitted a long report to Deputy Minister Cory from Banff. After leaving Great Falls, he proceeded to Missoula where he picked up Ayotte. They hired a team and drove 80 miles to the Flathead Reservation where he met Pablo and saw part of the buffalo herd, believed by the owner to contain 300 head. Douglas stated that his own estimate was 350. The negotiations, carried on with the help of Ayotte as interpreter, revealed that Pablo wanted to sell all his buffalo. Douglas obtained an option, valid to July 17, 1906, for the entire herd at $200 per head, subject to a down payment of $10,000 and the balance on delivery. Douglas strongly recommended the purchase as the animals were pure-bred, and stressed the importance of closing a deal before the United States Government learned of the proposed departure of the animals from Montana. In closing, Douglas commented:

"In my opinion the scheme is quite feasible and could be carried out successfully. It would certainly be a great advertisement for Canada, as, with the wild herd in the North and this bunch, Canada would own 8/10 of all the buffalo living, and including the herd here, there should be a thousand head in five years with ordinary luck."34

Existing departmental files covering the period from late June, 1906 to January, 1907, are devoid of any correspondence on the proposed purchase of buffalo. However, undoubtedly there was some unrecorded activity, for it developed later that an item of $100,000 was included in the department's estimates for 1906-07. In passing, it might be recalled that the fiscal year for departmental business then commenced on July 1, and any delay in negotiations probably was due to budget uncertainty.

This assumption is given credence by the contents of a memorandum forwarded many years later by Commissioner Harkin of the National Parks Branch to the Deputy Minister of the Interior on April 20, 1929. This communication dealt with the early history of the buffalo purchase and included the information that "The matter appears to have stood pending the passage of a vote by the House of Commons of $100,000 for the purchase of the herd".35

The inclusion of funds in the estimates for any fiscal year usually required the approval not only of the Minister of the department concerned but also that of the Cabinet. The writer was informed years later in August, 1969 by Mabel B. Williams that "We owe the Pablo herd to the Honourable Frank Oliver, who persuaded Sir Wilfred (Laurier) to buy it". Laurier was Prime Minister from 1896 to 1911. Miss Williams had served with J.B. Harkin on the Minister's secretariat from 1901 to 1911, and on the formation of the National Parks Branch in 1911, became one of the original members of Commissioner Harkin's staff.

There seems no doubt that Howard Douglas, while superintendent of Rocky Mountains Park, strongly advocated the purchase of Pablo's herd of buffalo and urged his Minister, Frank Oliver to obtain the concurrence of the Prime Minister and his cabinet. An article which appeared in the Edmonton Journal following Douglas' demise in 1929 strengthened this supposition, and stated that W.S. Fielding, then Minister of Finance, and Arthur Sifton, Chief Justice of Alberta, had extended their support.36

Buffalo Purchase Approved

By early 1907, Ayotte's repeated representations, Davies's letters and Douglas's persistence, all had paid off. On January 9, Deputy Minister Cory advised Douglas by letter that it had been decided to buy the Pablo herd at $200 per head, provided the buffalo were pure bred. Cory asked Douglas to obtain more information on the quality of the herd, and if satisfied, to make the necessary arrangements for the transaction, based on delivery at Elk Island Park. This request was passed on to Alex Ayotte through Ben Davies. Negotiations, however, were accelerated after Cory received a letter from Douglas dated January 17, with a clipping from an unidentified newspaper, which stated that the American Bison Society at Washington had undertaken to buy all buffalo herds in the United States. Douglas suggested that if the department was at all anxious to buy the Pablo herd, a deal must be arranged at once and a deposit made.

This letter brought immediate results. The Deputy Minister referred the letter to Frank Oliver, the Minister, and recommended that a telegram be sent to Douglas "to close a bargain for the herd". Oliver concurred, and after being notified, Douglas arranged to meet Ayotte at Great Falls and proceed with him to Missoula. On February 4, Douglas was able to report to Cory that he had obtained a new option expiring on March 1, 1907, covering the purchase of the buffalo at a cost of $200 each, together with the sum of $18,000 for the delivery of the animals in sound condition at Edmonton, Alberta. A deposit of $10,000 in Pablo's bank at Missoula also would be required.

Alternative Agreements Drawn

An Ottawa legal firm, McGivern and Haydon, was engaged to draft a suitable form of agreement with Pablo. This was reviewed by the department's legal adviser, T.G. Rothwell, who recorded his misgivings over the desirability of paying over to Pablo, prior to the delivery of any buffalo, a deposit of $10,000. Accordingly, duplicate copies of two separate agreements, signed under the seal of the department by W.W. Cory, the Deputy Minister and, witnessed by J.A. Cote, his assistant, were forwarded to Howard Douglas for completion by Pablo. Agreement 'A' provided for payment of $10,000 to Pablo on delivery of the buffalo at Edmonton, whereas Agreement 'B' entitled Pablo to receive $10,000 on execution of the document. Both forms of agreement called for the delivery of not less than 300 and not more than 400 head of buffalo; guaranteed the animals to be pure bred; and provided for payment of $200 per head in addition to the sum of $18,000 for delivery to Edmonton. The latter amount was subject to a deduction prorata for each buffalo that was found on inspection to lack pure bred qualities. Under either agreement, the deposit of $10,000 was to be applied to the overall cost of the buffalo delivered.37

New Agreement Completed

On arrival at Pablo's ranch with the agreements — already completed on behalf of the department — Douglas found himself dealing with a shrewd but honest vendor. Pablo had two main objections to the terms of the agreements, and refused to sign either of them. First of all, he did not want to undertake delivery of his buffalo beyond the nearest rail shipping point at Ravalli, Montana. He also would not commit himself to the delivery of more than 150 head. As Douglas explained, Pablo agreed that he had admitted ownership of 350 buffalo the previous autumn, but had not seen them since. Consequently, a number of them might have died during the current winter, a very hard one on wildlife, and he thought the Canadian government might insist on the delivery of 300 head whether or not he had them.

Douglas solved his problem by taking Pablo back to Missoula where the latter had a trusted adviser in the local bank manager. With the aid of this official and Alex Ayotte, who sat in as interpreter, a new agreement was drawn, signed by Pablo, and witnessed by the bank manager on February 25, 1907. Patterned after original Agreement 'B', it called for the delivery at Edmonton of 150 buffalo, subject to the provision that the sale covered the entire herd, with the exception of 10 heifer calves and two bulls which Pablo wished to retain. Other changes included a clause providing for the examination of the buffalo for quality of breed before shipment, and finally, if less than 300 head were delivered by the vendor, a deduction of $60 for each animal under that number would be made from the shipping allowance of $18,000.

The agreement in duplicate, after approval by the department's legal adviser, was completed by the Deputy Minister. One copy, together with a draft for $10,000 in gold, was forwarded to the manager of the First National Bank in Missoula for delivery to Pablo. The department's copy of the agreement was turned over to the chief accountant of the Department of the Interior for safe keeping. Its eventual fate is unknown, for it cannot be found on the files dealing with the buffalo purchase. One copy of the uncompleted Agreement A' and two copies of the uncompleted Agreement 'B' were returned to the department by Douglas. Although the return of the second copy of Agreement 'A' was requested by the Deputy Minister, it is not on file.38 It must have been retained by Douglas as a souvenir. Its possession by Thomas Douglas, a son of Howard, was disclosed in an article which appeared in the Edmonton Journal on September 1, 1955.

Temporary Destination Selected

Meanwhile, consideration had been given to the selection of a suitable area for establishment as a buffalo park. Howard Douglas had suggested a site in either of the Sarcee or the Stoney Indian Reserves east of Banff, but another plan was adopted. An examination of Dominion Lands records at Ottawa revealed that a large area of relatively vacant land was available east of Battle River in Alberta, between the Wetaskiwin branch of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the main line of the Grand Trunk Pacific railway then under construction. This area was examined by J.A. Bannerman of the Dominion Lands office at Edmonton and pronounced suitable for buffalo range. On August 6, 1907, Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, signed a memorandum to the Commissioner of Dominion Lands ordering the reservation from settlement of about 160 square miles of public land.39 A few sections within the proposed reserve had been granted to the Hudson's Bay Company and to the Canadian Pacific Railway and arrangements were made for the surrender of these holdings in return for vacant land to be selected elsewhere.

As some time would be required to adjust land titles, fence the new park, and erect administrative quarters and housing for the park staff, plans were made to deliver the 1907 shipments of buffalo to Elk Island Park east of Edmonton. This area of 16 square miles had been reserved in 1904 for the preservation of elk, and a contract had been awarded in 1906 for its enclosure by a strong wire fence. One of the group which had been instrumental in having the elk park established was F.A. Walker of Fort Saskatchewan, who, in 1905, was elected a member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. Walker was requested by Deputy Minister Cory to use his influence in having the fence completed by the contractor not later than the end of May, 1907.

In March, 1907, Howard Douglas had informed the Deputy Minister that he had undertaken to make the necessary shipping arrangements for Pablo, which would involve the use of the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Canadian Pacific Railway lines. The buffalo would be loaded in cars at Ravalli, Montana, south of Pablo's ranch, and it was hoped to make the run to Edmonton in not over 36 hours. On arrival at Edmonton, it was planned to switch the cars to the Canadian Northern line, which would permit unloading at Lamont, a short distance from the north boundary of Elk Island Park.

The Buffalo Roundup

The roundup and shipment of the herd began in May, 1907. Pablo's buffalo had never been herded, and were as wild as the original animals of the plains. Although Pablo secured the services of the most experienced cowboys he could assemble, and bought the fastest horses obtainable, the task of rounding up and loading his buffalo took more than four years. During the first year, some 75 riders, including Charles Allard, Jr., a son of his former partner, took part. Norman Luxton, described the roundup as follows:

"Day after day these untiring men and horses surrounded the wild herds of buffalo in the Flathead Reservation, and three times in only six weeks of daily drives were they successful in getting any of the buffalo to the corrals. The buffalo, when they found themselves being urged from their native pastures, would turn on the riders and in the wildest fury, charge for the line, scattering to all parts of this cactus-grown country the dare-devil cowboys."40

On reaching the corral at Pablo's ranch, the buffalo lost some of their spirit. The drive down the Mission Valley to the railway was accomplished without too much difficulty, and not until they reached the loading corrals was any serious trouble encountered. This is how the Daily Missoulan described the loading in its May 29, 1907 issue:

"But at the sight of these loading pens the big beasts attempted to back away. Their speed, however has been checked, and they cannot run over the line of horsemen that is drawn close around them. Gradually they are worked into the big pens as they are wanted for loading, and when they are once in the corrals the real trouble of loading begins. The pens are built as strongly as they can be made. . . . Once in the pen, the animals are cut out, one by one, and run into the loading pen. They are wild and by this time angry. A few pawings at the earth, a toss of the mighty head, and the imprisoned bull looks around him. A narrow gate is open and it seems to him to lead to liberty. Through the opening he dashes, the gate swings behind him, and he is in the chute that leads to the car."

"Perched on a running board along the chute is a big Indian with his lariat loop swung wide open. As the buffalo lunges forward below him, he drops the noose over the angry head. A turn around a snubbing post and the noose is tightened and the animal is held fast. Bars are thrust behind his back so he cannot back out; then he is under control and is eased into the car. . .

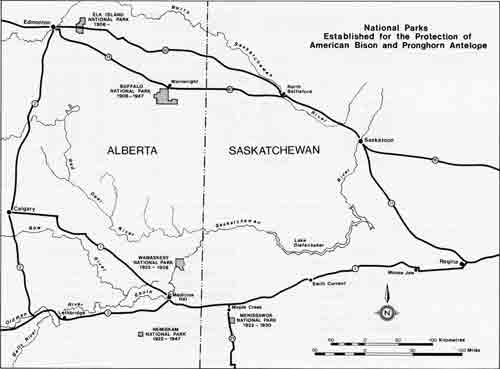

"The loading has been accomplished with but one serious accident. One bull so injured himself that it was necessary to kill him. In an incredibly short time the carcass was skinned, the meat distributed among the Indians, and the head and robe packed away for presentation."41