Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 5

Excavations at Lower Fort Garry, 1965-1967; A General Description of

Excavations and Preliminary Discussions

by James V. Chism

Excavations

Principal Residence

During the 1965 field season, tests were initiated

along the west wall and annex of the principal residence (Fig. 2; item

26; Fig. 4; item 1) or "Big House" at the request of the restoration

architect. The main structure had been built in 1831-32 and the annex in

1840. The structural and functional history of the house was complex

(Ingram 1970a). The most obvious changes to the outside of the house in

1965 were the addition of a kitchen at the north end of the main

structure and the building of a wide veranda, all by the Motor Country

Club in the 20th century.

4 Site plan of Lower Fort Garry.

(click on image for a PDF version).

1 Big House

2 Palisade

3 Barracks-Storehouse

4 Fur Loft-Retail Store

5 Troop Latrine

6 Southwest Bastion

7 Smokehouse-Oven Complex

B Troop Canteen

9 Blacksmith Shops

10 Farm Manager's Residence

11 Grain-Flailing Barn

12 Road

13 Loading Area of Road

14 Malt Barn-Grist Mill-Sawmill-Lathe Room

15 Malt Kiln

16 Distillery-Brewery-Storehouse

17 Storehouse

18 Beer Cellar

19 Lime Kilns

20 Storage Cellar

21 Boatyard-Boatshed Area

22 Miller's Residence

23 Stableman's Residence Area

24 Horse Stable

25 Ox Stable

26 South Cow Barn

27 North Cow Barn

28 Lime House Area

29 Prison Root House

30 Penitentiary

31 North-West Mounted Police Barracks

32 Museum and Bell Tower

33 Bake Ovens

34 Powder Magazine

35 Ice Houses

36 York Boat Shelter

37 Engineer's Cottage

38 Outbuilding of Cottage

39 Parking Lot

40 North-West Mounted Police Stables

41 Middens Tested

42 Outbuildings of Barracks

43 Outbuildings of Penitentiary

44 Reputed Well Location

45 Carpenter Shop-Hospital

46 Doctor's Office

47 Undocumented Building

48 Outbuildings for Big House

49 Meat Warehouse

50 Reputed Stable

51 Reputed Cemetery

|

5 Aerial photograph of Lower Fort Garry.

(Department of Mines and Technical Surveys) (click on image for a PDF version).

|

The house and annex were still standing structures

and archaeological research was requested to determine original ground

level and to investigate the possibility of basement window and stair

wells.

Tests carried out in 1965 and follow up excavations

in 1966 led to unanticipated results. An open areaway was discovered to

have paralleled the west wall of the Big House. This in turn was

paralleled by a driveway or apron with a dolomitic limestone rubble base

and a crushed brick and dolomitic limestone surface. The driveway also

paralleled the north wall of the annex. Salvage excavations were carried

out in 1966 when it was decided to place a steel-reinforced concrete

collar around the entire house and annex. This led to a brief and

largely inadequate investigation of earlier veranda alterations,

drainage systems, and the discovery of an outhouse built into the

veranda and against the house wall of the north end of the main

structure. Work directed by Peter Priess subsequent to that reported

here has added considerable detail to the nature of the open areaway,

the driveway, ground levels, fencing and another possible outhouse

associated with the Big House.

Areaway

Excavation along the west wall of the Big House

revealed a highly disturbed, stone-lined areaway paralleling and

contiguous with the west wall of the main structure (Fig. 6). It was

interrupted by the annex and an L-shaped retaining wall which may have

housed a stairwell into the link between the main structure and the

annex proper. The probability is very high that the open areaway ran the

entire length of the structure prior to the 1840 construction of the

annex. In apparent support of this, the arrangement of doors and windows

near the south end of the wall is similar to that at the north end.

6 Areaway along the west wall of the Big House.

|

The general configuration of the areaway was only

approximately apparent. It was roughly 14 ft. wide, as much as 6.5 ft.

below original surface and 7 ft. below 1966 surface. It was thought that

a slope led into a 4 ft. wide gravel walkway along the house wall. It

was further thought that construction of this slope had begun with an

unnecessarily elaborate mortared stone fill at the north end, and was

quickly abandoned for a more practical shallow rubble riprapping as work

proceeded south. Later work which will be reported by Priess showed this

to be in error, a fact attributable to the placement of our profile

trenches and to our fallacious attribution of all red crushed brick

scattered over the surface of the slope to the driveway parallel to and

contiguous with the areaway. Priess found that one concentration of red

brick rubble was associated with an oven which had been neatly missed by

our trenches. He also found that rather than a riprapped slope, the

original areaway probably consisted of a series of stepped retaining

walls. In all likelihood the end wall of the areaway consisted of a

single stone thick, steeply sloped retaining wall. No such stone wall

remained. Evidence of the end wall was only an earthen cut bank with an

80° slope which had a slight flare along its upper margin. This would

have been impossible to maintain as an earthen slope. This situation was

similar to retaining walls at the distillery, the L-shaped latrine

behind the fur loft-store and the store on the left bank of the creek.

In all instances, stone was laid against an almost perpendicular

slope.

The lowest layer of fill in the areaway was an

angular gravel and clay mixture. Its thickness and slope varied

according to the configuration of the underlying rubble bordering the

house. This fill was roughly level and approximately 0.1 ft. thick and 4

ft. wide. A ceramic drain 0.62 ft. in diameter covered loosely with

dolomitic limestone was found in this strip. A trench for this drain cut

through the ground outside the north end of the areaway. Drain tiles of

this style would probably not have been locally available until the last

quarter of the 19th century. The body of the tile is strikingly similar

to material recovered for the project by James Henderson at the site of

the 1879 to 1910 Doidge Pottery in East Selkirk, Manitoba some 8 miles

from Lower Fort Garry (Henderson 1970). The 1969 discovery of a

dolomitic limestone slab with a 0.1 ft. wide, 0.2 ft. deep cut channel

and another by Priess in 1968 indicate that an earlier and very

different drainage system was in use while the areaway was open. Priess

has been able to uncover more details of the earlier system and suggests

that it connected to a system which ran under the Big House itself. The

remainder of the fill consisted of patches of black and grey clays,

sometimes with angular and rounded gravels. The angular gravel was

crushed dolomitic limestone which was probably produced at the fort

quarries, and the rounded gravel probably came from the gravel ridge

north of the fort enclosure. Flower beds placed on the filled areaway

contained a mixture of fill and post-fill material to a depth of 1.5

ft.

One can presume on structural grounds that the

areaway was constructed in 1831 and 1832 at the same time as the Big

House. If the installation of a new drainage system was the first stage

of filling the areaway and if ceramic tile was not locally available

until 1879, then archaeological evidence indicated that the areaway was

filled after 1879. This has now been confirmed by Ingram, who has found

documentary evidence for the filling of the areaway soon after 1885.

Because of the mixed nature of the fill, artifacts found in it can only

be said to be pre-1885 material from unspecified areas of the site, some

possibly being from the gravel ridge north of the enclosure. The only

datable artifact from the fill below flower bed level was a single hard

paste earthenware sherd, datable in manufacture from 1867 to 1890.

Stairwell

The stairwell which led into the link between the

main structure and the annex had a 1.6 ft. thick, 6.0 ft. high mortared

rubble north wall with an exterior length of 16.7 ft. set on a 0.5 ft.

plank footing. There was a 0.6 ft. wide, 0.6 ft. high ledge running

along the interior base of this wall. The east end of this wall abutted

the main structure at a filled-in basement window. The west wall was 2.1

ft. wide, had an exterior length of 6 ft., had no shelf and its base no

plank footing, and abutted the north wall of the annex at a filled-in

basement window. The original height of these walls was not detectable

although a post-1885 photograph of this area indicates that they might

have stood two feet above the ground level of that time.

The west wall of the main structure served as the

east wall of the stairwell and the 7.8 ft. of annex wall between the

outside of the west stairwell wall and the northeast corner of the annex

served as the only archaeologically detectable portion of the south wall

of the stairwell. An old partition line was found by the restoration

architect on the west wall of the main structure 9.3 ft. from the

abutment at the stairwell wall. A 2 ft. wide stone slab footing was

found centered on this wall line and extending 9 ft. to the east wall

of the annex. A 0.5 ft. footing corresponding to the 0.6 ft. shelf on

the north stairwell wall ran along the south stairwell wall and bridged

the 9 ft. gap to the main structure. Possibly, the stairwell had

north-south running floor boards and these shelves and footings acted as

joists. The slab footing possibly supported another wall linking the

annex to the main structure as well. This would mean that the floor plan

enclosed by the walls would have been L-shaped.

Portable artifacts recovered from within the

stairwell and link included several 20th-century pharmaceutical bottles

made by a post-1904 fully automatic process. There would have been

access to the link through the open areaway until the mid 1880s:

therefore the assumption is that the stairwell was probably made of

pirated areaway stone at the time of its filling.

Driveway and Fences

A 17-ft. wide dolomitic limestone and brick driveway

bordered the upper margin of the areaway. The surface of the roadway was

0.66 ft. to 0.83 ft. below present ground level and appeared to be

continuous with the upper edge of the slope, although a 20th-century

sidewalk constructed along the upper edge made the determination of this

condition difficult. At the corner of the annex, the limestone rubble

was continuous with that observed along the annex wall in 1965. This

suggests the possibility that an earlier brick driveway had a surface

which was below window level at the annex. Later, a more substantial

limestone rubble base may have been added and brick spread over this.

Since a profile has not been cut at a point more distant from the annex,

it is also possible that one may find the limestone rubble to have been

the earliest base but to have stopped short of the annex. Brick rubble

observed under limestone next to the annex in 1965 tests could have been

the tailings of the overcoat at the sides of the road, and the overlying

limestone rubble could have been a later levelling fill after the basement

windows of the annex had been blocked off. The driveway curved to

the west and paralleled the north wall of the annex and probably

extended to the west gate. The present driveway follows the annex wall

without paralleling the west wall of the main structure.

A photograph taken about 1881 (Fig. 7) showed the

west leg of the driveway. An 1871 drawing (Fig. 8) indicates the west

leg but not the north leg of the driveway. Instead, it shows around the

Big House a solid fence broken only by the front and back gates.

Additionally, it depicts a fence running from the north fence toward the

northwest corner of the Big House. Another drawing of 1873 (Fig. 9)

differs from Figure 9 only by showing no extra fence running toward the

corner of the Big House. The 1881 photo and another dating from sometime

shortly before 1920 (Fig. 10) both show a fence running north-south in

this approximate position, although by 1920, the style of fencing

appears to have changed from an elaborate open style to a simple picket

fence. The combined implication of these historical clues could be that

fencing divided the front and back yards of the Big House. It could also

mean that an extension of the fencing bordered the areaway along its

western margin either to prevent accidental falls or easy access, or

both. If a driveway was extended to the north, such a fence would have

bordered its eastern margin. Later work by Priess has hopefully

clarified some of these possibilities.

7 The interior of the fort before 1881 (Hudson's Bay Company,

Winnipeg).

|

8 Birdseye view of fort enclosure, 1871 (Public Archives of

Canada).

|

9 Birdseye view of fort enclosure, ca. 1873 (Ottawa Public

Library).

|

10 The Big House, ca. 1920 (Hudson's Bay Company Winnipeg).

|

The above-mentioned 1965 tests concerned with the

annex indicated that dressed stone at the northwest corner extended only

0.85 ft. below the extant surface. A 0.25 ft. layer of grey clay covered

the lower 0.16 ft. of this dressed stone and the base of a post extended

through this layer and the outer margin of a builder's trench and

penetrated 9.21 ft. into the underlying undisturbed yellowish grey clay.

This was interpreted as indicating a former ground level of 0.5 ft. to

0.61 ft. below the 1965 surface.

This level was approximately even with the top of the

sealed annex basement window sill. After the windows had been sealed

this level was overlain by a 0.33 ft. layer of limestone rubble mixed

with clay which extended outward from the annex wall for two to three

feet. Underlying the northern margins of the limestone rubble was a 0.16

ft. layer of bright orange brick rubble. A 0.5 ft. dark soil layer used

as a flower bed was over these layers in the test area.

The brick and limestone rubble did not extend further

west than the post near the corner of the annex. It may be that these

rubble layers were associated with the driveway and that a fence

associated with the post would shielded this spot from scatterings of

road surfacing. In 1965, there was no historical data available to the

archaeologist to confirm this. Photos showing the Big House in 1881

(Fig. 7), before 1911 (Fig. 11), and in the 1920s (Fig. 10) respectively

show this segment of fence. The 1881 photograph indicates that the fence

is made of approximately 6 ft. high pickets and probably

functioned as a screen for the privy. The same photograph

appears to confirm the ground level striking the basement window

sills.

11 Fort interior, ca. 1911 (Hudson's Bay Company Winnipeg).

|

Veranda

Explorations on the east, south and north sides of

the Big House revealed stone and wooden porch supports pre-dating the

veranda built by the Motor Country Club. All measurements along the east

wall were taken from a chalk line running the full length of the east

wall which had been set up to compensate for the concave nature of the

wall.

Five dressed and eight undressed stones, ranging in

distance from 5.4 ft. to 6.6 ft. east of the chalk line, interpreted as

part of a veranda support system, were found along the east wall. The

veranda represented would not have been narrower than the maximum

measurement. Some portions of the upper stone surfaces were showing

above the thin layer of rubble covering the area. A profile was cut from

the east wall of the Big House to six feet beyond the fourth stone from

the north. A layer of mixed fill and rubble overlying black earth

containing some limestone and wood chips from construction activity was

found to be 0.62 ft. thick at the stone and to dip toward the Big House

foundation. A sharp dip within 1.5 ft. of the foundation was interpreted

as the upper margin of the builders' excavation. A stone-bottomed trench

was found paralleling the east wall of the house three feet east of the

veranda stone. The walls of this trench did not appear to cut through

the fill, suggesting that the trench might have been contemporary with

house construction. The support stone appeared to have been set into the

fill. Either the stone was added as a later improvement to the veranda

or it was simply set into construction spoil when the veranda was added

after the main structure had been completed. The former alternative has

been favoured because of the discovery of 14 timbers 0.4 ft. by 0.8 ft.

set perpendicular to the east wall of the Big House and underlying the

fill. These timbers were also thought to be veranda supports. If so,

then the fill was clearly spread over the area after the veranda was

built and the stones would have been associated with a later

construction phase. The distributional patterns of the stones and timbers

have no direct relation to each other; however, they do both have

several instances of approximately 8-ft. spacings. This would suggest

that they represent an earlier and a later veranda with wooden and stone

supports respectively. Because an upright could be set anywhere on a

long timber footing, it is not safe to estimate veranda width from the

timber length.

Three timbers lying against the east house wall and

set into the uppermost level of fill may be associated with the stone

supports. The northernmost was a roofing collar 0.18 ft. by 0.55 ft. by

16.4 ft. The other two, along with several other timbers running

east-west, were discovered during new construction and exact dimensions

were not obtained.

A similar situation of stones and timbers was found

along the south wall of the Big House, where stones were recorded

ranging 5.70 ft. to 7.74 ft. from the wall. The veranda would have been

at least 7.74 ft. wide on this side. Seven timbers set at right angles

to the south wall were excavated from under the fill and two timbers

were found lying against the wall in the upper fill. Two timbers

parallel to the south wall were found below the fill at the southwest

corner of the Big House main structure where a link between it and the

1840 annex had been built. There were no timbers where early photographs

showed stairs.

Two timbers perpendicular to the north wall were

uncovered near the northeast corner. One measured 0.16 ft. by 0.4 ft.

and the other, 0.2 ft. by 0.6 ft. Both extended northward for an

indeterminate distance below surface rubble at a depth of 0.62 ft.

Attempts to uncover any veranda foundations which

might be present on the north side of the Big House were largely

unsuccessful. A summer kitchen had been built by the Motor Country Club

on this location and the ground was heavily disturbed.

A post measuring 0.3 ft. by 0.3 ft. was found at the

intersection of lines paralleling the north and east walls at a

distance of six feet from these walls. It had been sunk 3.1 ft. into the

underlying clay. If this was a fence post, then either one of several

verandas was only six feet wide or else it pre-dated any veranda. The

same is true if it was a post for a horse rail. The width of the earlier

veranda on wooden supports could have been six feet wide or less. In

contrast to this figure, Ingram (1970a) has noted that in 1851 orders

for veranda timbers specified that no major timbers be cut shorter than

8.5 ft.

The accumulated evidence seems to indicate that a

narrower than six foot veranda with wooden supports was rebuilt to a no

less than 8.5 ft. wide veranda with stone supports in 1851. Portable

artifacts found had a dating range overlapping the entire period, and so

contribute nothing to the question.

Veranda Privy

A pit cribbed with tamarack was discovered against

the south wall by construction workmen in 1966. Three walls were of log

and the main structure of the Big House formed the fourth. The pit's

east wall was set flush against the east wall of a chimney and its

dimensions were approximately 8 ft. by 8 ft. by 6 ft. deep. The cribbing

displayed tenoned ends on horizontal members and mortising on vertical

members at the northeast and northwest corners. It was not possible to

determine whether construction had been post-on-sill or post-in-ground.

However, a concentration of artifacts near the bottom along with a lime

concentration and the presence of certain unmistakable signs made it

very easy to determine the pit's function as a privy. Its incorporation

into porch construction may have been unique. Certainly its proximity

to the open areaway to the immediate west and its abutment against the

house would have raised certain drainage problems. Of course, it is

possible that it post-dated the filling of the areaway.

Portable artifacts from the pit were numerous and at

least provide some clues for dating. Although most of the ceramic

material is datable in manufacture between 1847 and 1867, at least two

hard paste earthenware vessels were datable in manufacture to 1873. One

also presumes that tableware would be used as long as possible before

discarding it, limiting its usefulness for precise dating. Several

ceramic fragments were from dolls and toy tea sets suggesting that a

little girl was among the occupants of the house during the period

represented by the pit fill. Glass containers, the other major category

of artifact from the pit, suggested that not only was there a little

girl living in the house, but that a baby was there as well and that the

period represented by the fill was late despite the early clustering of

ceramic dates. Several Mellin's Food Company baby food bottles were

found, datable between 1884 and 1928. There is some confusion about

changes in the company name and it is possible that 1899 might have been

the earliest that the company used the "Mellin's" name. A "Conrad

Budweizer" (1877 to 1890) and a "Lee and Perrins" bottle with "JDS" on

the base (1877 to 1920) also supported a late terminal date for the pit.

Therefore, it cannot be assumed that the earlier ceramics mixed

throughout suggest an earlier use for the pit. The suggestion would be

that in the late 19th century one kept ceramics but threw away glass

containers much more readily as their manufacture had become

inexpensive.

Ingram (1970a) noted that there was considerable

alteration and construction around this general part of the house in

1874 anticipating the arrival of the Hamilton family. He noted that

Company officers from Winnipeg used the house as a summer residence for

their families in 1879, 1880, 1888, and throughout the 1890s, dates and

circumstances which fit the nature and dates of artifacts in the

fill.

One might argue that it would not be expected that

anyone would dig an outhouse so near an open areaway, and that it was

dug after 1885. The proximity of the post-1885 drainage tile suggests

that this was the anticipated drainage for the privy to keep moisture

away from the basement wall. Ingram noted that it had been recommended

that an "old lean-to and shed" at the north end of the Big House should

be torn down in 1911, but there is no record that this was done. The

fact that detailed records kept by the Motor Country Club did not

mention the destruction of this structure after 1911 might be viewed as

negative evidence for a 1911 filling of the privy.

Annex Basement Floor

Limited investigation was carried out to determine

the nature of the original flooring in the Big House annex basement.

When workmen removed the recent flagstone flooring, wood fragments

indicated the possibility of wooden floor joists. Careful clearing of this

surface near the southeast corner indicated that the fragments were

oriented north-south and were spaced 1.5 ft. apart. It was difficult to

judge joist width, but it appeared to be somewhere between 0.4 ft. and 0.6

ft. The south wall had been notched to accommodate these joists; these

notches were 0.5 ft. deep, were on a 2 ft. centre and were directly in line

with joists from the floor above. No portable artifacts were

recovered.

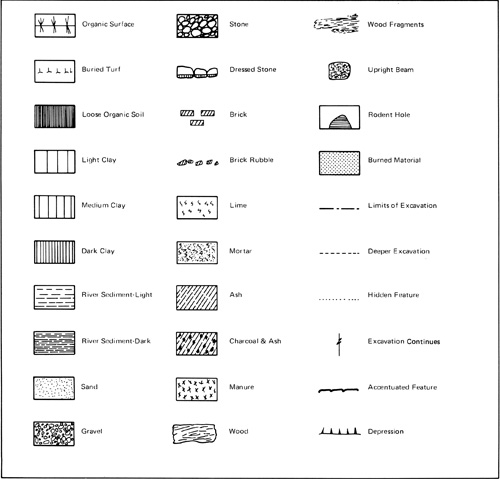

Symbols used in drawings. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Prison Yard and Palisade

A portion of the prison yard and palisade directly

east of the penitentiary was excavated in 1965 (Fig. 4; item 2). The

palisade was reportedly built after June, 1870, to enclose the exercise

yard when this stone storehouse was being used as Manitoba's first

provincial prison from 1871 to 1877 (Miquelon 1970). The palisade and

yard are listed on the Watson map (Fig. 2) as item 6. The excavation was

an attempt to determine the construction and state of preservation of

the palisade and to confirm its location. On the ground, a low ridge

could be seen in the approximate position indicated by Watson.

A trench and the below-ground portions of the pickets

were found as well as some evidence of the exercise yard enclosed by

the palisade (Fig. 12). The trench varied in width from 2 ft. to 5 ft.

and was 4 ft. to 4.4 ft. deep with slightly sloping sides and a flat

bottom. It had branches with no pickets and slightly shallower lobes

extending laterally from the main trench line at irregular intervals.

The trench cut through the lower portion of a dark top soil with

considerable limestone gravel near its base; a gravelly clay stratum

which contained lime and sand which was often but not always at its

bottom, and finally through a black undisturbed soil. The trench

contained mixed gravelly fill. Although one was sure that some of the

uppermost portions of the soil was a sod dressing, a clear delineation

could not be made. Because the trench cut through all except the

uppermost part of the dark top soil, all layers except the top one may

be interpreted as clearly pre-dating June, 1870.

12 Plan of the prison palisade. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

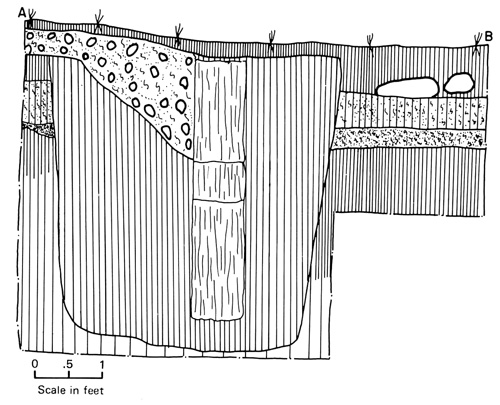

13 Profile of the prison palisade.

|

The second layer from the surface contained mixtures

of clay and mortar and may be interpreted as a mortar puddle. This

probably reflects the relative dating of nearby construction sites

pre-dating the palisade. The underlying undisturbed soil exhibited the

characteristic natural profile for the site.

Pickets found in the main trench appeared to consist

primarily of round and quadrilateral timbers, but some appeared to be

planks. It was not always possible to be confident of measurements

reflecting original dimensions; however, the few "planks" were

approximately 0.1 ft. by 0.5 ft.; round pickets ranged between 0.3 ft.

and 0.75 ft. in diameter, and the quadrilateral pickets, while

irregular in shape, were in the same range of size. They extended to a

depth of 4 ft. where excavated. A sample of the wood was identified as

white oak.

The palisade line had a different configuration than

was expected. This can be seen by a comparison of Figures 2 and 14. Two

right angles exist which were not indicated by Watson in 1926. It is

interesting to note, however, that there was an empty trench in the

position indicated by Watson for that section of the palisade which he

misdrew.

In general, a heavy limestone gravel layer directly

under the sod abuts the palisade from the inside of its enclosure. This

may reflect (1) an attempt to make digging out difficult; (2) a desire

to minimize muddy conditions; (3) debris from a prisoners'

stone-breaking operation, or (4) all three.

Although recent historic evidence brought to light by

Ingram (1968) indicates that a palisade was erected (or repaired) for a

mental asylum in 1885, there was no indication of more than one

construction phase noted in excavations. "Empty" trench lines were

checked at their point of juncture in an attempt to find whether they

were dug at different times, but no indication of such was found.

Limestone slabs turned on edge near the penitentiary appeared to retain

gravel within the enclosure at that point. It was originally thought to

be the edge of a gravelled prison yard. Based on later observations of

gravel walkways this particular arrangement might suggest a walkway with

containment of the gravel by upturned slabs set into the ground. Such a

walkway may be seen at the west end of this same still-standing stone

building.

The palisade is shown in an 1873 drawing (Fig. 9) and

a photograph dated between 1871 and 1880 (Fig. 14). The height of the

palisade was clearly no less than 10 feet. The palisade has a gable-like

addition to offset the height of the north wall of the fort where the

two intersect northeast of the penitentiary.

14 Lower Fort Garry from the northeast, ca. 1871-80 (Public Archives

of Manitoba).

|

There were few portable artifacts found at this

location, and of the four datable ceramic fragments found, only one had

a manufacturing date range which fell within the prison or even later

asylum period. The other dated fragments had earlier date ranges. The

material does not assume much importance when one realizes that both the

trench fill and other fill was probably brought in from other areas.

Certainly the gravel in the fill suggests that these contexts are not to

be trusted, since gravel would have to be from outside the

enclosure.

Storehouse-Barracks

Watson (1928) suggests that the storehouse near the

east wall of the enclosure (Fig. 4; item 3) was used as a barracks by

troops of the 1870 Wolseley Expedition. Its use as a storehouse

(warehouse) was described by Robinson in 1879 (Miquelon 1970), and

Ingram (1970b) noted that Company correspondence refers to it as a

storehouse. Both Watson and Ingram indicate that it was moved to Colvile

Landing in 1881.

The date and technique of construction of this

building are a problem. It has been assumed that it was the structure

referred to in Miquelon as being built in 1870 for accommodation of

troops; however, the dimensions cited for that building were 24.5 ft. by

50 ft. and do not conform by any standard with findings described below.

Watson described the structure as "frame," but this was also of little

assistance since several techniques may be described by this term

including the so-called "Red River frame" which is a general term for

several varieties of post-on-sill log construction.

On the ground, the building was indicated by shallow

linear depressions forming a large rectangle bisected lengthwise by

another shallow linear depression. It was in the general area indicated

by Watson's 1928 map.

Photographs show the building clearly. A photograph

of 1871-80 vintage (Fig. 14) and another taken in 1880 (Fig. 15) show a

two and one half storey structure with weatherboard siding and

distinctive half windows under the eaves. Two drawings, one of 1871

(Fig. 8) and another of 1873 (Fig. 9), relate the same information.

15 Fort enclosure, 1880 (Geological Survey of Canada).

|

Excavations were oriented toward determination of

accurate location, dimensions, and construction details. It was also

hoped to recover artifacts, stratigraphic information, or both which

might help clarify its age.

The structural remains found (Fig. 16) were those of

the main building and a more lightly constructed porch-like structure at

the south end. In terms of location and dimensions, the Watson map was

in close agreement with the in-ground situation with regard to the main

building, which consisted of a 32 ft. by 72 ft. foundation with a stone

central footing bisecting the structure along its long axis. This

foundation varied in width from 2.2 ft. to 2.6 ft. and was constructed

with a 3.5 ft. deep trench.

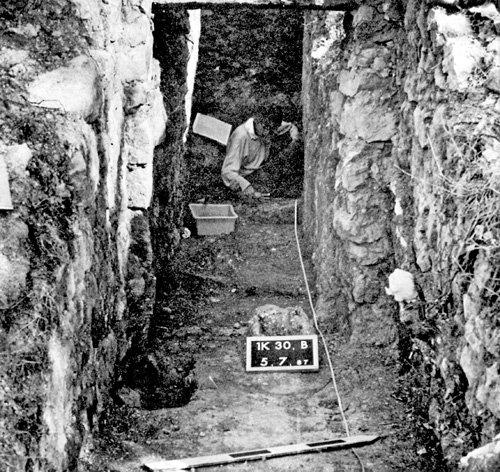

16 Storehouse-barracks as excavated looking north, with the prison

palisade in the background.

|

Physical stratigraphy was consistent throughout the

area. A thin sod with dark humus covered the operation to a depth of 0.2

ft. At the base of this level was a great deal of fragmented wood. The

grain of the wood fragments was primarily parallel to the long axis of

the building and was probably from flooring. Deteriorated mortar of the

foundation began directly beneath this flooring at an average depth of

0.2 ft. and cut through a thin layer of scattered mortar and gravel.

Beneath this appeared a level of dark loam which was 0.5 ft. thick mixed

with occasional sand. This was underlain by a second thin layer of

scattered mortar, which became thicker at the north end and indicated

that a mortar-mixing area was located north of the structure.

Signs of heat were noted near the north end of the

building on both sides of the central support foundation. The area noted

in the northeast quadrant was a circular grey discolouration 3 ft. in

diameter which began in the second layer and extended downward to the

bottom of the third layer. The area in the northwest quadrant was fired

red, but was below the lowermost mortar and must have pre-dated the

building. The final area of heat noted was another circular grey area

3.3 ft. in diameter occupying the same stratigraphic position as the

one in the northeast quadrant. The two grey areas probably indicate

stove positions. The red area was more likely the result of an open

fire.

The porch-like extension at the south end of the

building proper added another 12 ft. to the over-all length of the

structure. It consisted of a thin rubble and mortar footing which

overlapped the edges of the main foundation. The width of the footing

was the same as the foundation except along their common wall along the

south end of the main building foundation. Here the mortar and rubble

footing ranged in width from 1.0 ft. to 1.5 ft. In this small rectangle

were two heavy limestone blocks set into holes dug 1.7 ft. deep. The

1880 photograph and the two drawings discussed above indicate that

stairs might have gone from both ends of this porch to an upstairs

door.

A number of large limestone blocks was found near the

north end of the building apparently associated with the third layer.

Although this stone suggested a porch at this end of the building, no

clear indication of such a structure was found.

One of the empty trenches associated with the

neighboring prison palisade passed through the extreme northwest corner

of this excavation. It was outside the building and cut through the

mortar levels, as had the palisade trench, which would support the above

interpretation as to the relative ages of these features. A pre-June,

1871 date of construction for the barracks-storehouse was suggested by

relative dating.

While excavation demonstrated that the structure was

supported by a stone foundation with a central footing for supporting

floor joists, that a lighter structure existed at the south end, and

that floor joisting would probably have had an east-west orientation to

support north-south oriented floorboards, there was nothing in the

archaeological record which would have argued for a log superstructure

as opposed to a lighter form of frame construction. If the building was

approximately ten years old when it was moved away, it must have been

reasonably solid, and no traces of decomposed lower margins were left

behind to provide the needed clues.

All dated ceramics found pre-dated the period of the

building unless it was built considerably before 1870. An 1849 to 1877

Lee and Perrins bottle with "ACB" on its base was the only dated glass

noted. Again, it appears that the glass container might be a more

sensitive time indicator than ceramics.

A preliminary nail count has indicated that of a

total of 1,213 nails, 4.95 per cent were wire, 75.10 per cent were cut

and 19.95 per cent were wrought. As other structures are discussed, the

reader will see that these are generally consistent percentages for a

building put up in the late 1860s and taken down in 1881.

Fur Loft-Retail Store

In 1967, testing and excavation was carried out in

the area surrounding the extant fur loft-retail store located inside the

fort enclosure and near the south defense wall (Fig. 4; item 4). Work

here pre-dated the planned restoration of that stone structure. The

structure was believed by Ingram to have been built in 1832 while

Governor Simpson was still living on the site.

Basement Stairwell

An 1871 drawing (Fig. 9) and a sketch of 1857 or 1858

(Fig. 17) show an off-centre basement entrance in the east end of the

loft-store which could be seen as a partially filled door from inside

the basement of the structure in 1967.

17 Portion of a sketch showing basement

entranceway at east end of fur loft-retail store (left), 1857-58

(John Ross Robertson Collection, Metropolitan Toronto Public

Library).

|

A stone-lined stairwell of dolomitic limestone was

found 7.8 ft. south of the northwest corner of the fur loft-retail

store. In plan view, the outside dimensions were 7.3 ft. north-south by

10 ft. east-west. The lateral retaining walls were 2 ft. wide, 3.2 ft.

deep at its maximum depth at the base of its steps, and consisted of

mortared, split-faced stone and rubble set in a random pattern and

resting on the underlying steps and on the stone landing at the bottom

of the steps. Height of the remaining walls was 3.2 ft.

The 1857-58 drawing shows an inclined entranceway

cover sloping upward toward the building, standing well above ground

level. Clearly, then, much of the lateral wall had been removed.

The landing was a 4.5 ft. square area immediately

outside of and centered on the filled doorway. It was paved with a

double thickness of limestone slabs, each being 0.4 ft. thick. As

indicated above, the slabs extended under the lateral retaining walls,

and under at least the lowermost of three stone-based steps descending

into the entranceway from the east. It also extended into the stone

filled doorway for an indeterminable distance.

The outside opening for the doorway was 5.2 ft. from

the surface of the stone floor to the bottom of the outside lintel. The

inside opening was 6 ft. from the bottom of the doorway to the bottom of

the inside lintel. The outside lintel was 0.22 ft. lower than the inside

lintel, making the bottom of the inside doorway opening 0.58 ft. below

the bottom of the outside doorway opening. This suggested that a step

was involved within the doorway fill. No dressed stonework was found in

either the interior or exterior faces of the opening.

The entranceway steps were represented by two

reasonably discernible mortared stone step bases and one badly disturbed

base for the head step. The stones extended under the lateral walls. The

lower two steps had a rise of 0.9 ft. including the stone base, a layer

of levelling mortar and a wooden tread. The wooden tread would not have

been more than 0.19 ft. thick. Tread width was more of a problem. Lowest

base was 0.7 ft. and the middle was 1.5 ft. while no meaningful

measurement could be made on the top step. Horizontal pressures

including frost action might have affected tread width.

A 2.2 ft. wide by 4.5 ft. deep rubble-bottomed

drainage trench running east toward the river bank had been cut by the

construction of the entranceway or was in use at the same time.

Immediately datable portable artifacts were not

recovered from deposits below a flower bed at this location.

Covered Winter Entrance

Ingram reported verbally that his researches

indicated a covered entrance door to the main floor at the west end. The

door was still extant in 1967 and paint traces on the wall indicating

the height and width of a covered storm entrance were recorded in an

architectural survey of the structure by Mr. Richard Fairweather of the

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

A test at the doorway revealed no archaeological

evidence of the covered storm or winter entrance.

Troop Latrine

The Dominion Survey of 1874 (Fig. 3), a sketch of

1871 (Fig. 8) and a sketch of 1873 (Fig. 9) show a small building

directly south of the fur loft-retail store which was not present in

1967 (Fig. 4; item 5).

Negative photographic evidence can at least add one

detail about the structure itself; it did not stand any higher, and

probably not as high as the defense wall, since it does not show over

the wall in photographs of the fort taken from the south in 1858 (Fig.

18) or 1880 (Fig. 15).

18 The fort enclosure from the south, as photographed by H.L. Hime in

1858 (Public Archives of Canada).

|

A slight depression in this area between the building

and the south defense wall indicated the presence of a filled and

settled pit. The depression was found to have been a narrow L-shaped

dolomitic limestone lined pit (Fig. 19). The early illustrations gave no

indication of an L-shape, suggesting that the stone-lined pit was

enclosed within a rectangular structure. The long leg of the pit ran

parallel to the south defense wall and the short leg was at right angles

to and abutting the defense wall. Evidence of the building's

superstructure was missing. However, the pit had two major structural

subdivisions. The first was a heavily built section occupying the

western end of the long leg. The second and more lightly built section

occupied the remainder of the long leg and the entire length of the

short leg.

19 Plan of troop latrine. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The western section of the structure had outside

dimensions of 10 ft. by 16.5 ft. The foundation was 2.2 ft. to 2.7 ft.

thick, and was composed of rubble, split faced and squared stone set in

uneven coursing but with considerable inbowing due to horizontal

pressure. At a point 4 ft. from the inside margin of the west wall, a

row of pickets formed a partition wall. Brown and black fill with heavy

building stones near its bottom extended downward to a depth of 2 ft. to

3.5 ft. Underlying this was a layer of ash and general refuse to a depth

of 5.5 ft. This was in turn underlain by a 0.3 ft. to 0.6 ft. brown

layer, a 0.4 ft. to 0.8 ft. layer of lime, and a 0.45 ft. to 1.15 ft.

brown organic layer for a total depth of 7.35 ft. A builder's trench

along the foundation went down to a total foundation depth of 8.2 ft.

below the present surface. The pickets had been driven into the bottom

three layers of fill but not into undisturbed clay below the pit. The

picket partition was clearly an addition made sometime during the

deposition of the thick ash-refuse layer.

The eastern section consisted of the remaining

portion, of the long leg and the entire short leg. The north foundation

was 11 ft. to the turn and the south foundation was 5.5 ft. long to

where it turned. The east foundation was then 15.5 ft. and the west

foundation 9.1 ft. The nature of stonework changed from the wide and

mortared vertical wall of the western section to an unmortared or

perhaps lightly mortared retaining wall with an 85° slope and a fine

rubble fill between the stone facing and the earth behind. The facing

consisted of a single thickness of squared and splint-faced limestone

set in uneven coursing which approached random coursing when large or

small inclusions were made. The rubble placed behind this facing was to

bring unlike-sized facing stones into line. Also unlike the other

section, slump from horizontal pressures was practically non-existent.

Seepage of groundwater limited excavation into the

fill; however, the same layer of brown fill that was found in the top of

the western section was traced to a depth of 5.5 ft. next to the defense

wall before excavation was discontinued. The bottom 1.5 ft. to 2 ft. of

this stratum contained a mixture of wood fragments, granite boulders and

limestone blocks.

It was found that the defense wall was only 4 ft.

deep where it was abutted by the pit. Park staff reported that the wall

was normally 6 ft. deep. In addition, it was found that the retaining

walls had wedge-shaped openings beginning at a depth of 4 ft. where they

abutted the defense wall. Presumably these continued to the bottom of

the walls and may have been for drainage.

A 0.2 ft. to 0.5 ft. thick layer of mortar and rubble

was found under the sod in the area between the long leg and the defense

wall. This would have been the area included in the structure if it was

rectangular.

At the angle between the defense wall and the east

edge of the east retaining wall, it could be seen that the two walls

shared a common builder's trench, indicating that the L-shaped trench

was dug at the time of defense wall construction. This would have been

sometime about 1845 (Miquelon 1970).

The structure most probably functioned as a latrine

and refuse pit. The nature of the organic layer in the western section

indicated the latrine function most unmistakably. The shallowness of the

defense wall at this point and the wedge-shaped openings also speak for

drainage systems. No immediate and necessary rationale occurs to the

author for the two construction types involved in the two separate

sections of the pit. Possibly the thick mortared rectangle replaced a

collapsed section of earlier wall. It may have been necessary to build

the wall separating the two sections simply to add strength to the

construction.

The size and nature of the superstructure was only

generally indicated in the early drawings. A rectangular single-storied

building of uncertain height with gable ends was indicated, but clear

evidence reflecting on superstructure was not noted in the

archaeological record, although the presence of considerable mortar and

rubble in the angle between the pit and the defense wall would suggest

that a stone or "half-timbered" building may have been involved. Seemingly,

however, if that were the case, a foundation beyond the pit would

also be expected. A light stone footing with a rubble-filled,

post-on-sill superstructure might explain the presence of the stone

detritus without the additional requirement of a foundation. Such a

footing could have been removed, although a slight rubble-filled

depression would then have been expected. Such a depression was not

noted but its absence would be less disturbing than the absence of a

stone foundation from an all stone structure.

A large number of portable artifacts were recovered

from excavations of this "latrine." Mr. H.S. Sprong of Selkirk

recollected placing at least portions of the dark top layer into a

depression in this area when he was employed by the Motor Club as a

gardener, and 20th-century material was expected in that layer.

The dated ceramic objects from layers below the dark

upper layer were all of patterns and companies with manufacturing date

ranges which could be consistent with almost any period of the fort's

history, with dates clustering in the 1846 to 1867 period and no known

20th-century marks or patterns which could not also have been earlier.

However, glass containers were often clearly 20th century, including a

bottle made by Dominion Glass with April, 1931, registration date on it

from the brown layer beneath the thick ash-refuse layer. It was only in

the bottommost brown organic layer, which was not fully excavated, that

no machine-made bottles were found; however, glass from that layer may

still have only dated back to the 1880s or 1890s. Glass was less

plentiful from outside the pit and did not present a basis for dating

the rubble found in the angle of the "L." Logic would suggest that a

prestigious organization such as a country club would not have an

uncovered outhouse pit on its grounds. Since there is material deeply

deposited in this pit dating around 1930, some 16 years after the club

was established, it follows that this structure or a later structure

over the same pit was still standing in 1930. Because it was an

elaborate stone-lined pit, it would have been cleaned out whenever it

was full rather than being abandoned for a slightly new location, a

pattern which is still considered standard today for more simple

facilities. Earlier material from this elaborate pit is probably lining

the river bottom.

Southwest Bastion and Adjacent Features

In 1967, excavations were conducted within and around

the extant southwest bastion (Fig. 4; items 6, 7) preparatory to planned

restoration of this structure.

The bastion was built about 1845 (Miquelon 1970). A

drawing of 1846 (Fig. 20) showed the bastion to have three chimneys.

Standing to the north of the bastion in the same drawing was a complex

of three small structures. The largest appeared to have been a

rectangular, single-storied, gabled wooden building. Next to it was a small

rounded structure and an equally small square or rectangular stone

structure. Each of the two small structures had a chimney. It appeared

that the rounded one was an oven while the square or rectangular one had

the appearance of a small smokehouse although it might have been a

second oven. There was no documentary evidence bearing on these three

buildings. Research by Ingram indicated that a large oven was inside the

bastion (Ingram: personal communication). Excavation was oriented toward

investigation of the interior oven and the nearby buildings with general

testing of the area likely to be disturbed in restoration

activities.

20 Southwest bastion, 1847 (Glenbow Alberta Institute).

|

Smokehouse-Oven Complex

The area within the angle of the southwest corner of

the defense walls was excavated (Fig. 4; item 7). The stone foundation

of a 12.8 ft. by 7.8 ft. structure with a north-south long axis was

located 46.7 ft. north of the bastion (Fig. 21). The west and south foundations

were 1.4 ft. wide by 0.1 ft. deep and the east and north were 2

ft. wide by 1.0 ft. deep. A layer of yellow clay had been packed into

the area enclosed by the foundations. No other evidence of flooring was

found. This was probably the small stone "square or rectangular"

structure in the 1846 drawing.

21 Area north of the southwest bastion with the smokehouse-oven

foundations as viewed from the bastion.

|

Immediately to the east of the foundation was a

concentration of rubble and mortar. This may have been destruction

rubble from the stone building, from the chimneys, or even from the

ovenlike structure in the drawing. Scattered patches of mortar, rock and

wood fragments could have been debris from the larger building;

however, no clear pattern emerged.

Bastion Interior

The recent flooring placed inside the bastion by the

Department of Indian Affairs was partially removed in the west room, in

the location of two chimneys in the 1846 drawing. No evidence beyond a

single, loose, blackened stone was found which might have related to an

oven or chimney. However, highly decomposed joists of an earlier floor

were found 1.2 ft. below the surface of the recent floor. Traces of six

east-west running, 0.7 ft. wide joists set on 3.3 ft. centres were

resting in irregularly shallow 0.7 ft. wide notches on a 3 ft. wide

stone apron ringing the inside of the circular bastion wall. The apron

was only one stone or 0.4 ft. thick as found, although it might have

been disturbed when the new floor was put in.

Datable portable artifacts were not observed in a

brief survey of the small collection from either the bastion or the

small complex of buildings: however, in a universe of 1,016 nails from

the location where the complex of buildings should have been, 55.20 per

cent were cut, 30.90 per cent were wrought and 13.90 were wire. This

sample would be more consistent with construction in the 1850s rather

than the pre-1846 date shown by the drawing. The shallowness of material

in what was probably a heavily travelled area may account for this

inconsistent impression.

Troop Canteen

A building south of the fort enclosure thought to

have been a troop canteen (Fig. 4; item 8) was partially excavated in

1965 and 1967. Watson identified it on his 1928 map (Fig. 2; item 122)

as a log men's house and canteen which was torn down around 1884. Ingram

(1965) reflected Watson's opinion, but discovered data in 1968 which

suggested that the log structure might have been built for the Canadian

government in 1870 (Ingram 1968). The same data referred to a building

built for the government being sold and moved in 1877 but might not have

been this specific one.

No illustrative material was available which clearly

related to this structure.

On the ground, a long, narrow, raised outline with

undulations perpendicular to the long axis could be seen in the location

indicated by Watson.

Excavation uncovered a very fragmentary situation

(Fig. 22). The north and south walls were missing and a 22 ft. to 23 ft.

portion of the west wall was also gone. Measurements taken on the remaining

wood gave a length of 82.5 ft. for the east wall and 60.3 ft. for the

west wall. The building was 15 ft. wide. The oak sills were 0.7 ft. to

0.9 ft. square. As was so often the case, these figures represented the

logs' deteriorated and compressed dimensions rather than original

size.

22 Plan of the troop canteen. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The northern end of the structure had been built on a

layer of fill composed for the most part of a mixed clay. Variations in

thickness of this fill suggested that the northern part of the building

was built over what had been a natural depression running toward the

river. This depression had been filled with clay to provide a level

construction surface. Thickness of the fill was greatest at the

northeast corner: it decreased to the west and eventually disappeared

toward the south.

The sills and sub-sill supports had been laid on this

levelled floor. Notches were cut in the inside edge of the sills apparently

to hold the floor joists, which were set on 3.3 ft. to 10 ft.

centres. They were fastened by clasp-headed wrought nails. The notches

were 0.38 ft. to 0.4 ft. wide and 0.2 ft. to 0.3 ft. deep. The joists

were probably larger than the above dimensions which might represent

only the size of the tenon. No joists were found. The sills had been

packed with clay to hold them in place. This clay appeared in profile as

a distinct yellowish layer easily separated from other layers.

The sills had been provided with support in the form

of either a short piece of timber or a block of limestone. Toward the

northern half of the structure, these two were alternated with the first

one on the north end being of wood. Location of these supports was near

but never under the notches for the joists. Toward the south end of the

structure, there was a breakdown in the alteration between wood and

stone and a decrease in spacing between them.

The sills were mounded over with a combination of

mortar and grey clay, which overlaid the yellowish clay. This sill

covering may have been chinking or mud plastering left behind when the

logs of the superstructure were removed, or some of it may have been

banked against the sill to help seal the building against severe winter

temperatures. These mounds aided in approximating the ends of the

building. Perpendicular to the long axis of the building at about 10 ft.

intervals was a series of six ridges of this same destruction debris

which probably represented partitions since they overlaid the

artifact-littered surface of the yellowish clay.

A wooden stoop was found along the exterior of the

east wall. It consisted of north-south running plank fragments laid on

two 0.22 ft. wide by 0.2 ft. thick and 3.5 ft. long east-west running

joists spaced 3.2 ft. apart.

Details of construction gleaned from the

archaeological investigations were few. The orientation of the

structure's long axis was north-south and thus the floor joists would

have been east-west. The sub-sill timber and stone supports suggested a

post-on-sill type of construction with each support being under an

upright post. The lack of mortar and stone detritus further suggested a

structure largely of wood. The building may have been divided by a

series of seven 10 ft. x 15 ft. rooms, if the ridges inside the building

represent partitions. Entrance to the structure was on the east side

where the stoop was uncovered. Other stoops may have existed but did not

survive; or only one entrance may have been used in order to conserve

heat in the winter.

If the building was post-on-sill, then there was

probably a series of windows associated with the uprights, but

indicative glass concentrations were absent from the archaeological

record.

A heavy concentration of artifacts, mostly of a

highly miscellaneous nature was found under the destruction debris.

Again, the dated ceramics predated the suspected period of occupation. A

"Davis Painkiller" bottle with a high mould line to the "finish" may

date to the 1880s plus or minus a few years. This might support the

original Watson and Ingram proposal that the structure was removed in

the 1880s. Datable clay smoking pipes included two "Dixon-Montreal"

(1877 to 1894) pipes which would indicate that the deposition of

material was at least as late as 1877 but most probably later. If this

building was built in the same year as the troop barracks-storehouse,

then one might expect the two buildings to have similar nail

percentages. This suggestion is apparently borne out, for a total of

1,811 nails from the canteen was made up of 1.05 per cent wire, 23.52

per cent wrought and 75.43 per cent cut while the barracks-storehouse

had 4.95 per cent wire, 19.95 per cent wrought and 75.10 per cent cut

nails.

Blacksmith Shops

An excavation was oriented toward recovery of

structural, functional and dating information at the location of the

blacksmith shop south of the fort enclosure (Fig. 4; item 9; Fig. 23).

Work was begun here in 1965 and continued in 1966.

23 Blacksmith shops looking south.

|

Miquelon (1970) and Ingram (1970b) both repeatedly

discuss activities at Lower Fort Garry which would require a blacksmith.

Nevertheless, Ingram (1968) reported that little new structural

evidence of a blacksmith shop beyond window pane size (7-1/4 in. by

8-1/4 in.) had been found to extend the data gathered from local

informants by Watson (1928). Watson reported the position of the

blacksmith shop (Fig. 2; item 123) and recollected that it was log. He

also noted an explosion at (accounts do not say in) the

blacksmith shop in 1877, which has been interpreted by both Watson and

Ingram (1970b) as indicating that the shop was destroyed at that time.

Ingram was more cautious and allowed for the possibility of it having

been rebuilt.

On the ground observations indicated a low mound in

the approximate position indicated by Watson.

Excavation revealed two shops, a small earlier shop

separated by a layer of rubble from a larger, later shop and annex. The

earlier shop has been designated blacksmith shop I and the later shop,

blacksmith shop II.

Blacksmith Shop I

Excavation clearly indicated that blacksmith shop I

was an 18 ft. by 20 ft. log structure (Fig. 24). There was no direct

historical evidence found by Ingram which bears on the beginning or end

date of this earlier structure. Certainly, the activity at the fort of

the middle 1840s would have been impossible without the aid of a

blacksmith: however, it also seems likely that there would have been a

blacksmith shop from the earliest period of the fort.

24 Plan of blacksmith shop I. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Disaster or rotting of the lower logs would have been

necessary to have forced the razing of blacksmith shop I before the

construction of blacksmith shop II, for had it been a simple matter of

needing more room, the Company could have accomplished this without

dismantling the old shop. The sleepers and joists of shop I were below

ground level and had clay banked against the outside. So a combination

of rot and expanded activity at the fort might have been the factors

leading to its end. On the basis of activity at the fort, a date of

between 1857 and 1865 is suggested for its replacement. This was when

large-scale farming, ship building and steam equipment were introduced.

This is also the period in which Ingram (1970b) notes that work was

being done in the shop for the upper fort as well.

The west or back wall sill was approximately one

foot below the original ground surface. A contour drop of between 0.6

ft. and 0.8 ft. occurs from the back to the front or east wall. This

meant that as a levelling device, the front sill was probably set into

the ground less than 0.5 ft. The sills were squared-off oak timbers.

They displayed an excavated width of 0.85 ft. but decomposition and

compression made the thickness difficult to measure. One presumes that

an original size would have approximated one foot. The sills were lapped

at the corners, right over left. It could not be determined whether the

sills were fitted into each other with square saddles although

comparative architecture would suggest this to be the case.

Underlying the corners were diagonally oriented

planks 0.7 ft. wide, 0.2 ft. thick and 5 ft. long. They did not appear to

be rounded on the underside. Again, one should suggest that compression

and decomposition would have reduced the thickness of these corner

supports.

Fragments of planking underlaid the east and south

sills at irregular intervals.

Floor joists ran north and south, or the long way of

the building which was not the case with larger or more rectangular

structures on the site. The joists had excavated dimensions of 0.5 ft.

to 0.6 ft. wide and 0.1 ft. to 0.2 ft. thick. The easternmost joist would

apparently have been long enough to span the building and was set on a

2.8 ft. centre with the east sill. The second joist line required two

sections to span the structure, the south section being at least 11.5

ft. long, its centre 4 ft. from the centre of the easternmost joist, and

the north section being 12 ft. long and on a 3.2 ft. centre with the

easternmost joist. The third joist line was similar to the second in

requiring two sections to make a complete span. The south section was at

least 10.4 ft. long and centred 3.8 ft. with the south section of the

second joist line. The north section of the third joist line was on a

4.2 ft. centre with the north section of the second joist line. The

fourth joist line was interrupted by the forge. The south span must have

been a 6 ft. board running between the south wall and the southern edge

of the forge. The north board was completely missing. Logically, there

would have been a 4.8 ft. long board running between the north wall and

the northern edge of the forge. A thin layer of crushed brick was found

under and particularly between these thin joists.

Two limestone slabs measuring roughly 2 ft. by 1 ft.

by 0.5 ft. were found approximately 2 ft. south of the north wall and on

either side of the north section of the second joist line. These have

been interpreted as anvil supports. They were probably not used as such

for the later shop as they were overlain by rubble which would have

created instability in a later anvil. Also, the westernmost of the two

stones was partially overlaid by a joist of the later shop.

Flooring consisted of east-west running planks of

from 0.5 ft. to 0.6 ft. in width with the bottom rounded in cross

section. Such planks reached a thickness of 0.1 ft. to 0.15 ft. and

could be the by-product of squaring timbers by sawing. Rosehead and

clasp head wrought nails secured them in place with a pattern of two

nails per board at a joist.

A stone forge was built against the west wall of the

shop, its intended size clearly 8 ft. by 6 ft. A 3.25 ft. deep ash box

was built into it one foot off centre to the north. The base was 0.5 ft

below and 1.5 ft. above the floor level of blacksmith shop I. In

general, masonry was random coursed from carefully cut but irregularly

sized squared and faced limestone with a rubble-filled interior.

Dressed stone was used occasionally as general

building stone in the forge base. This was first thought to have

indicated the re-use of stone from another building, but it is also

possible that a mason dressing stone on the spot for trimming the forge

openings would have been likely to utilize a reject in the base.

A number of manually mixed, wire-cut burned clay

bricks of slightly different sizes centreing around 0.73 ft. by 6.37 ft.

by 0.21 ft. were found. Their location near the forge suggested that

they had been used in the construction of the forge. Their presence

could be taken to suggest a brick chimney; however, due to the small

number found, it is possible that they only lined the breast of the

forge.

The detection of the area of greatest heat for the

forge allowed us to make several conclusions. Although the ash box was

off-centre, the fire was centred on the forge, and so, also, must have

been the breast. The proximity of the forge to the west wall also

suggested that a stone backing probably separated the fire from the log

wall, meaning that this was an all-purpose rather than a farrier's

forge.

A 5 ft. wide door at the approximate centre of the

east wall may have been indicated by three closely spaced supports under

that sill. These supports and those under the corners suggested that the

superstructure may have been post-on-sill construction.

As one would expect, there were many portable

artifacts reflecting the general function of the structure as a

blacksmith shop: however, we will reserve further specific comment on

the functional aspect of the material for the artifact reports. The

ceramic range of manufacture fell within or included the predicted

period for the structure. The presence of one hard paste earthenware

object with a registration date of 1865 strongly supports the hypothesis

that shop I was used until the great increase in industrial and

agricultural activity in the mid 1860s. Glass containers were not

plentiful; however, one champagne bottle appears to have been mould

turned suggesting that it could be dated to the latter part of the

1880s or even in the 1870s. In a collection of 233 nails, a surprisingly

small sample, wrought nails were 80.70 per cent of the total and cut

nails were 19.30 per cent. There were no wire nails.

Blacksmith Shop II

Blacksmith shop II was a log structure and must have

been the shop referred to by Watson in 1928. This later shop (Fig. 25)

was clearly an expanded facility built over the rubble of the earlier

shop and utilizing the same forge for its operation. The later

structure, measuring 26 ft. by 18 ft. lay directly over the west, south

and east walls of the earlier shop, but was 6 ft. longer on the north

side. It also included a 21 ft. by 14 ft. annex, its east wall being

flush with the east wall of the main structure.

25 Plan of blacksmith shop II. (click on image for a PDF version)

|

As in the case of the earlier shop, there is no

direct historical evidence of construction details for blacksmith shop

II.

The explosion at the blacksmith shop in 1877 might

have spelled the end of the later shop, but there is no way of

determining this satisfactorily. Certainly excavation provided no

convincing signs of such a disaster. From documentary evidence we can

only say that there was a shop which lasted until at least 1877.

As with the earlier shop, the sills of the main

structure were lapped at the corners, with extra planking reinforcing

the corners as well as the walls at regular intervals. The joists also

ran under the sills to act as bearing supports.

It appeared that after levelling the rubble of shop

I, the first stage of construction for the new shop was to set the

joists and plank supports into trenches and set the sills over them. A

similar "entrenched" effect might have been gained by settlement into the

unstable rubble construction surface. The joists ranged in size from 0.5

ft. to 0.65 ft. wide and from 0.09 ft. to 0.15 ft. thick. In a few

instances, the original outside surface of the tree could be detected,

suggesting that untrimmed logs have been sawn into planks.

The orientation of shop II floor joists and flooring

was at right angles to that of shop I. Also in contrast to the earlier

shop, the entire distance between the east and west sills was spanned by

a single plank for each joist.

Spacing of the joists was irregular. From north to

south the relation of joists to sills and to each other may be expressed

as the approximate distance from centre to centre. The first joist had a

2 ft. centre with the north sill. The second joist had a centre of 3 ft.

with the first joist The third joist had a centre of 3 ft. with the

second joist. The fourth had a centre of 2.5 ft. with the third. The

fifth had a 2.5 ft. centre, with the fourth. The sixth had a centre of

2.5 ft. with the fifth. The seventh had a 4.5 ft. centre with the sixth,

and the eighth a 4 ft. centre with the seventh, leaving a centre of less

than 2 ft. between the south wall sill and the eighth joist. There were

only the slightest hints that additional joists might possibly have

existed between the sixth, seventh and eighth joists. Extra supports ran

under the fifth and sixth joists where they ended in front of the

forge.

The sub-sill supports ranged in size from 2.5 ft. to

4.5 ft. in length, 0.5 ft. to 0.8 ft. in width, and 0.2 ft. to 0.5 ft.

in thickness. The corner supports bisected the angle formed by the

lapped sills. From north to south, the east and west wall sill supports

were set at a 7 ft. centre to the north sill; the second set of supports

was at a 9.5 ft. centre to the first set of supports, leaving a measurement

of 9.5 ft. to the centre of the south wall sill. The supports under

the north and south wall sills were in the approximate centre of those

sills, the north one being less than 0.5 ft. west of centre and the

south one being directly centred. The sills were depressed over these

sub-sill supports, suggesting that upright structural members bearing

weight were resting on them.

Sill dimensions as found ranged from 0.75 ft. to 0.95

ft. in width and 0.5 ft. in thickness. Ignoring the thinness of the

decomposed sills, reconstructed dimensions clustering around the one

foot mark would not be unreasonable for the sills. The sills extended

beyond the corners for an estimated distance of 1.5 ft. to 3 ft.

This overlap, also present at other excavated log

structures at Lower Fort Garry, is somewhat puzzling. The most simple

explanation would be that clay banked against the outside wall for

weatherproofing might have covered such an otherwise awkward protrusion.

If these long ends were protruding above ground at the corners, then

they were not only a constant hazard to walking but were also unusual.

To the author's knowledge, no standing structures of the period in the

Red River area display such unusual corners. Archaeologically, there

was no clear indication that the bottom sills were set below ground

level and that the overlapped corners were concealed. However, it would

be difficult to support the proposition that blacksmith shop II was of

simple lapped-corner construction because of the upright mortise and

tenon found protected by its proximity to the forge. The author has seen

log structures using combinations of post-on-sill and dovetail corners,

and while a combination of post-on-sill and lapped-corner construction

is not impossible, the remains of what might have been a mortise in the

southwest corner would mitigate against such a combination. It is also

possible that the original thicknesses of the sills were nearer to their

present 0.5 ft., thereby presenting less of a stumbling block, but this

seems unlikely too. In such an event, the mortise would have gone

completely through both sill members at the corner and such a hole would

have been archaeologically apparent. It is possible that the extensions

themselves were thinned, leaving the sills thick, but there is no

evidence to back this proposal.

The north-south oriented flooring of the main

structure was 0.5 ft. to 0.8 ft. wide and had a found thickness of 0.05

ft. to 0.09 ft. Floorboards were nailed to the joists with two nails at

each joist using chisel-pointed rosehead and clasp head wrought nails.

Only the sixth joist was noted to have four nails holding single boards

to the joist. There was no sign of extra wood at the north and south

ends of the floor for nailing, nor was there any indication that the

floor did any more than abut the north and south sills. There appeared

to have been some patching between the first and second joists from the

north.

Although there was a heavy concentration of iron

oxide scales southeast of the forge, there was no clear indication as to

the location of the anvil or anvils of blacksmith shop II. Possibly a

stone base was present, but the fallen stone from the destroyed forge

might have concealed its presence so it was inadvertently removed as

rubble. There might not have been a base except a tree stump as often

noted in comparative blacksmith shops. Although hinges, locks, and

other metal artifacts occurred in the ruins, their numbers indicated

that many were being made or repaired, so it is not practical to

comment on what ones might have been used in this building.

The annex to blacksmith shop II appeared to have

been much more lightly constructed than the main shop structure. The