|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 2

Archaeological Research at the Fortress of Louisbourg, 1961-1965

by Edward McM. Larrabee

Introduction

History the Site

By the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713,

France lost her major western Atlantic base of Placentia on the island of

Newfoundland. She also lost Acadia (mainland Nova Scotia), and retained

only Ile Royale (Cape Breton Island) and Ile Saint-Jean (Prince Edward

Island). It was necessary to find a substitute port, which had to serve

a variety of functions. The substitute had to be in a location that was

close to the Grand Banks fisheries; that did not freeze; that was

affected as little as possible by spring drift-ice; that was accessible

to the important trade from the West Indies and Europe;

and that could serve as a point from which ships-of-war could patrol the

major approaches to the St. Lawrence River and the large French

holdings in the interior of the continent. Finally it had to be a

harbour which offered protection from storms and which afforded a safe

place for the drying of fish, the outfitting of ships, the storing of

goods, and the loading and unloading of merchant ships. Louisbourg (Fig.

1), near the eastern tip of Cape Breton Island, met these

requirements.

1 Map of eastern seaboard of Canada and New England.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

The harbour of Louisbourg is about two miles long from northeast to

southwest, with a mouth about one mile wide (Fig. 2).

The effective width of the channel into the harbour is no more than a

quarter of a mile, as islands and shoals close the southern part of it.

The French fortified the harbour by means of a battery on the island in

the centre of the harbour mouth; another battery faced the island and

the entrance from the mainland; and a third battery was in the town

itself. The latter was on the relatively low, flat peninsula, Rochefort

Point, at the southern end of the harbour. As events in two sieges

showed, the defences of the harbour were effective.

2 Fortress of Louisbourg and vicinity.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

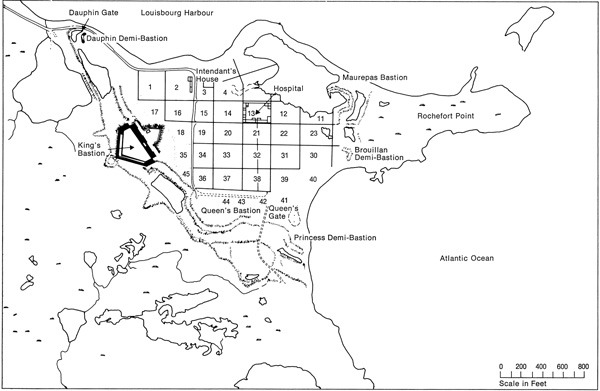

The landward defences of the town were not so successful because they

could be commanded by fire from hills to the west. These defences consisted of a

double-crowned work running on a line south and east from the harbour

to the sea (Figs. 3-4). Beyond these fortifications, which were founded

on low hills in the glaciated terrain, were broad marshes that were

expected to prevent any close approach of siege works. At a later date,

one bastion and a demi-bastion were added to the seaward defences of the

town at Rochefort Point. Enclosed within these walls was an area of

nearly 60 acres in which a town was laid out on a rectangular grid of

approximately 30 town blocks.

3 Fortress of Louisbourg.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

4 Vertical aerial photograph of the Fortress taken in the spring of 1961.

|

Effective construction began in 1720 and the major fortifications were

completed after two decades of hardships resulting from the effects of a

raw climate, salt air and poor materials on the masonry, difficulty in

obtaining pay and supplies, an inadequate labour force, and possibly

improper construction. The garrison of the fortress varied from about

1,000 to about 4,000 men. The normal civilian population of the town was

probably never more than 2,000, although refugees from the farming areas

to the north swelled the population in times of siege.

The first siege was conducted by New

England forces in 1745. The Royal Navy provided the blockading fleet,

but all other contributions were colonial. The besieging forces dragged

cannon across what had been considered impassable marshes to the hills

which commanded the main or west gate of the town at the Dauphin Demi-bastion.

This was the weakest point in the defences of this irregular

work. After a siege of seven weeks the walls were breached and an

assault was prepared. The defenders were almost out of munitions since

the siege had prevented any re-supply after the winter. At the pleading

of the townsfolk, the garrison surrendered.

The New England troops occupied the town and were eventually replaced

by troops from Great Britain. The year after the Treaty of

Aix-la-Chapelle, 1748, Ile Royale was returned to the French, who

strengthened the fortifications of Louisbourg and stood a second siege

in the summer of 1758. General Amherst was in charge of British forces,

but the systematic and energetic attack was under the direct command of

General Wolfe. Again the same weak points in the fortifications were

battered. Again the French were caught short of supplies at the end of

the winter, and the fortress surrendered. The main British base at

Halifax had an excellent harbour and so the British had little need of

Louisbourg. Fearing that at the forthcoming peace negotiations

Louisbourg might again be returned to the French, the British

systematically destroyed the fortifications (see Fig. 4 for craters

resulting from the British demolition). The French occupants had

already been sent back to France and the town was in a ruinous condition

as a result of the siege. A small British garrison remained until 1768,

when it was withdrawn to New England. The inhabitants of the town

comprised a few ex-soldiers and settlers, chiefly from Ireland. The

19th-century occupation of the site consisted of a few families who

fished and who farmed the now vacant space within the shattered walls,

or grazed sheep on all that remained of the French town and its

defences.

Disturbances of Area in the 20th Century

Before the present restoration project started, there had been some

excavation of one sort or another at the Fortress of Louisbourg. This

has affected all the subsequent work, and should be taken into

consideration. During the first decade of this century, D. J. Kennelly

"cleared the accumulation of the centuries" from several of the large

casemates on the right and left flanks of the King's Bastion, and

repaired the arches of these casemates (see Fig. 5 for terminology). He

also did work on the outside of the left flank. In 1904, road

construction crossed the ruins of the Chateau St. Louis and a monument

was placed inside the King's Bastion in 1926. Other commemorative

markers were also placed in this area which had been transferred to the

Department of the Interior in 1928 from the Department of National

Defence with the intention of eventually creating a National Historic

Park in Louisbourg. Between 1928 and 1931, the dozen or so late 19th- or

early 20th-century houses which were scattered over the fortress area

were removed. The last of these were taken down when the Museum and

Museum House were built in Block 34 in the mid-1930s. In 1940,

Louisbourg was formally established as a National Historic Park.

5 Fortress of Louisbourg; the citadel.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

During the 1930s there was major disturbance of the Chateau, a large

amount of the upper level of earth was removed, and the entire outline

of the Chateau foundation was stabilized above ground level. More

stabilization and clearing, along the line of Kennelly's earlier work,

was carried out in the casemates of the King's Bastion. Similar work was

done also in the south row of rooms in the hospital in Block 13 and at

the Intendant's house at the northeast corner of Block 2. While a

number of "relics" were saved from this work and were put into the

museum which was constructed on the site in the mid-1930s, there was no

controlled excavation.

Similar haphazard work continued during the 1940s and into the

mid-1950s. The entire perimeter of Block 13, enclosing the courtyard of

the hospital, was stabilized, and the fill in the centre of the

courtyard was bulldozed away. There was some additional stabilization

and repair at the Chateau. A road was cut through the Queen's Gate, and

the cut stones found there were used to build revetments. The road also

extended in front of the gate across the demilune and on to the glacis

by the Princess Demi-bastion.

Thus by the end of the 1950s, many of the most important parts of the

fortress had been affected by some sort of "development" or

ruins-stabilization. None of this had been accompanied by archaeological

investigation. In the summer of 1959, J. Russell Harper was sent to

Louisbourg by the National Historic Sites Service to do the exploratory

excavations which were to serve as an archaeological feasibility study.

His work identified excavation conditions, several types of structures

and artifacts, and the physical condition of buildings and objects in

all important areas of the Fortress. Although his work was not intensive

in any one area, it was useful for guiding later detailed investigation

(Harper 1959).

In the summer of 1961, a group from Acadia University did a

preliminary underwater archaeological survey of limited scope in the

harbour of Louisbourg, and located a number of wrecks (Hansen and

Bleakney 1962).

The Restoration Project

In the summer of 1961, the Government of Canada announced plans for

the reconstruction of a substantial portion of the Fortress of

Louisbourg. The project was to last for a number of years, to employ and

retrain men, to put money into the area, and to build a worthwhile

attraction for the tourist industry — all of which affects the

archaeology. Work began that summer on the clearing of an area for

administration buildings, laboratories and workshops. After the project

started, a recruiting program was carried out to find the historians

and archaeologists needed for research. This paper describes the

extensive archaeological program carried out to provide a basis for

accurate reconstruction.

|