|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 16

Table Glass from the Wreck of the Machault

by Paul McNally

The Glass

Table glass of French origin was restricted to one tumbler base,

badly crizzled and decomposed, and many hundreds of wine glasses of a

single type. There were in addition eight wine glasses of English

origin.

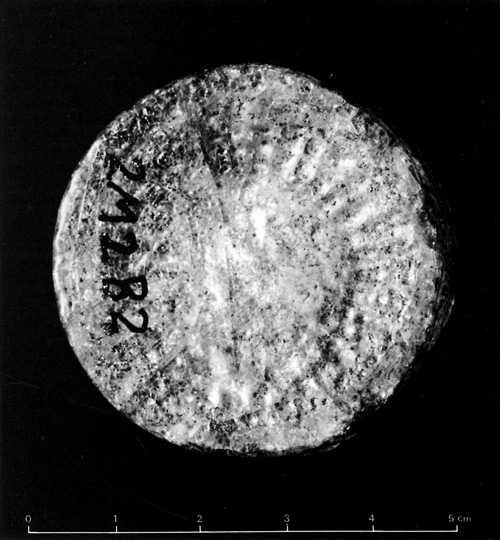

1 Base view of a small pattern-moulded French tumbler in crizzled

non-lead metal; mid-18th century.

(Photo by G. Lupien.)

|

The tumbler base (Fig. 1) is from a small pattern-moulded ribbed

non-lead tumbler typical of those manufactured in central and western

France in the middle of the 18th century (Charleston 1952: 18). The

crizzling is characteristic, and so is the tendency to turn brown or

pink in the course of decomposition. Similar tumblers are normal finds

at French sites in Canada with comparable occupation periods: the

Fortress of Louisbourg, Forts Beauséjour and Gaspereau, and Beaubassin

for instance.

No vessel count of the French stemware was undertaken because ice and

tidal action have reduced most of the examples to fragments and because

continuing excavations at the site produce more and more specimens. The

glasses so far probably number close to a thousand, with no significant

variation between examples except that stem height differs slightly.

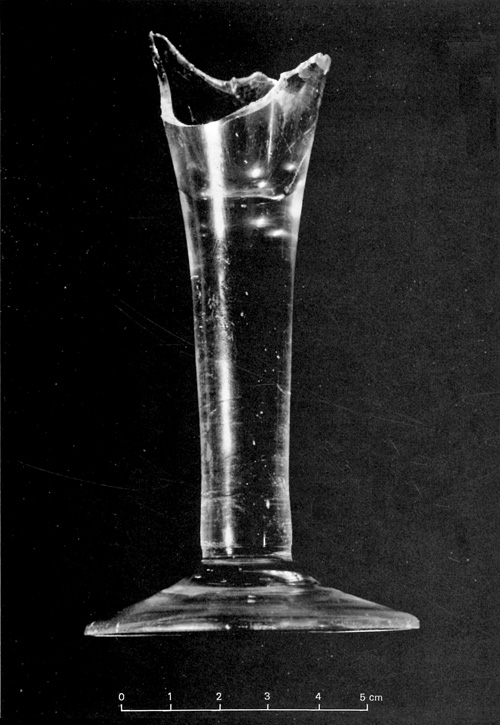

Capacity appears to be uniform. Shown in Figure 2 is the only wine glass

complete to a segment of the lip rim. The main feature is a hollow

six-sided moulded pedestal stem. The French called the form bouton

carré and evidently borrowed it from Bohemian glassmakers (Barrelet

1957: 114) though English collectors have long referred to such stems as

"Silesian." The glasses are of three-piece construction: the moulded

stem was welded to a round funnel bowl with a thick base, and a plain

conical foot was formed on the stem. In every case the foot has a folded

rim. In many cases the lower part of the stem is twisted slightly from

reheating the stem and attaching the foot; the variation in stem height

results from the same process. The glass has no lead content.

2 French wine glass with hollow six-sided moulded pedestal stem

(bouton carré) and round fennel bowl, non-lead metal; third

quarter 18th century.

(Photo by G. Lupien.)

|

Hollow pedestal stems were a normal French form of stemware in 1760.

They were common at the Fortress of Louisbourg, and some examples

recovered there were certainly deposited in the 1750s (Dunton: pers.

com.). Engraved examples illustrated by Barrelet (1957: Fig. 21) and

Haynes (1964: Pl. 62g) bear the dates 1758 and 1746 respectively.

Haynes remarks that it is not impossible that such glasses are English

(1964: 219). One might add that is it not probable either. While

engraved dates are not necessarily accurate, the size of the

Machault sample indicates the form's great popularity in the

third quarter of the 18th century.

The French wine glasses were scattered throughout the wreck, but were

concentrated on the port side, adjacent to the keelson and well forward.

The very number of glasses is sufficient to indicate that they were

cargo, and additional evidence is the fact that the feet show no wear,

which would have been the case had they been used to any extent. Why

they were included in the cargo is unclear. Documentary research has not

disclosed them among items requested from the crown by threatened

Montreal, nor among items actually shipped although wine of several

varieties does figure in both lists (Beattie 1968). The enterprise was

mounted by the crown, but evidently merchants and ships' officers could

speculate privately in commodities such as glass.

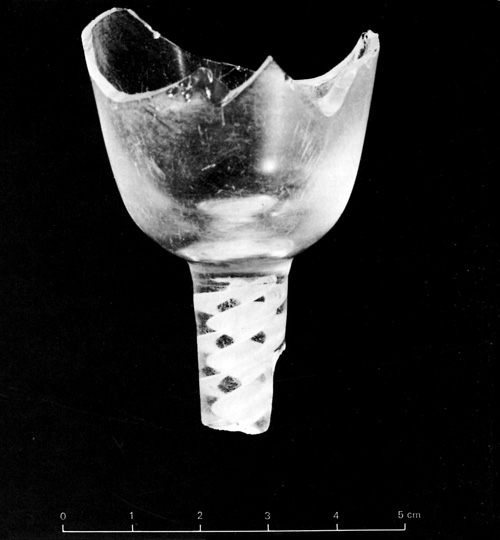

English stemware is represented by seven drawn plain stems with

trumpet bowls and a fragment from a glass with an opaque-twist stem. All

are of lead metal.

The tall plain-stemmed glasses were a fashionable style from about

1735 until the early 1760s in England (Hughes 1956: 88-9).

Rudimentary plain-stemmed wine glasses were in use as common ware

throughout the century and later, but there is a clear distinction

between these short-stemmed and usually clumsily made glasses, and those

made during the period in which the style was fashionable. Of the latter

it has been remarked: "Some would say that this [is] one of the most

beautiful English glasses ever designed" (Lloyd 1969: 60). The

Restigouche examples (Fig. 3), though they have lost most of their bowls,

show some of the gracefulness implied. They are drawn, or two piece,

glasses.

3 English wine glass with drawn plain stem, lead metal; fashionable

about 1735-65.

(Photo by G. Lupien.)

|

Opaque-twist stems enjoyed popularity in England from 1750 until 1780

(Thorpe 1969: 213-4). The stems were formed separately: cylinders of

glass in which enamel rods were imbedded were enclosed by an extra

gather of metal, then drawn and twisted to form long canes subsequently

broken into appropriate lengths. The Restigouche example has a round

funnel bowl and a double-series twist formed of a central and a

surrounding corkscrew, both in white (Fig. 4).

4 English wine glass with round funnel bowl, opaque double-series twist

stem, lead metal; 1750-80.

(Photo by G. Lupien.)

|

The presence of English glass in the French wreck requires some

explanation. Before embarking on a lengthy discussion, and lest it be

argued that too much is made of a chance occurrence, it should be

pointed out that the presence of English table glass at sites with

mid-18th century French contexts is a continuing phenomenon, witnessed

with certainty at the Fortress of Louisbourg and again at Fort

Beauséjour (McNally 1971:123). The converse is not true, or at least has

not shown itself to date.

In general, English glass deposited in French contexts probably came

from several sources. The French writer Paul Bosc d'Antic wrote in 1760:

"L'étranger consomme les quatres cinquièmes des glaces angloises . . .

aujourd'hui ils nous fournissent des lustres, des lanternes, des verres

à boire, des verres d'optique de toute grandeur, &c." (1780: 59).

This is evidence enough of a thriving if one-sided trade in glass

between France and England, and glass so obtained might easily be

forwarded from France to her possessions. Doubtless at least some glass

was brought to Acadia by New England traders (Clark 1968:180-2). Still

more could have been booty.

The most famous contemporary French observations on English table

glass come once again from Bosc d'Antic in 1760. They form as poor a

notice as a patriot might fashion against pernicious foreign

manufactures.

Les Anglois ne doivent point se flatter. . . . Leur cristal n'est

pas d'une belle couleur; il tire sur le jaune ou sur le brun, pour peu

que la couleur rouge de la manganèse domine. Il est si mal cuit, qu'il

ressue le sel, se crassit, se rouille promptement, est rempli de points

et nébuleux. . . . Il a encore un autre défaut capital, c'est d'étre

extrèment tendre. Ils vendent cher leurs ouvrages (1780: 60).

To be fair, the physical defects outlined had troubled English

crystal some decades earlier, but certainly no longer applied after

1750. Unless the English made a habit of sending inferior glass to

foreign markets, the criticism was unjustified, and might indeed be

turned against much French table glass at the time — witness the

tumbler base found at the Restigouche wreck, the primary identifying

feature of which is its tendency to deteriorate and discolour in a

certain manner. And certainly the faults and expense had little effect

on appetite for the product, as Bosc d'Antic himself indicates: "Il

n'est point de pays où les Anglois ne trouvent moyen d'introduire leurs

ouvrages de cristal et de verre" (1780: 59).

The English table glass on board the Machault might have been

purchased in France, or taken from one of the nine small British ships

captured by the French fleet in the Gulf of St. Lawrence before they

arrived at Chaleur Bay (Beattie 1968). If it had been obtained in

France, either for speculative purposes or for the personal wants of an

officer, it was certainly purchased in preference to the domestic

alternative; the large number of French wine glasses aboard the ship

attest to their availability. Such preference is emphasized by the

observation that English table glass was apparently available in France

only at specialized English shops (Barrelet 1953: 107). If the glasses

were taken from one of the captured English ships, more wine glasses

were not strictly needed on the French ship, though the stemware may

have served as souvenirs. In either case, their occurrence is the

product of preference rather than necessity.

The reason for French preference for English glass was at least

partly aesthetic. The French glass industry was at something of an

impasse. Supplies of wood fuel were dwindling, as they had in Britain

much earlier. Britain, of necessity using coal, had hotter and more

efficient furnaces. Having to cover their melting pots to exclude coal

fumes, British glassmakers found they could make glass freer of

impurities. These improvements, along with the development of lead

glass, were the foundation for an independent British commercial and

stylistic tradition. While the French were beginning to form their own

tradition, there was considerable distraction in the ease and short-run

inexpense of importation, as well as the influence on styles which such

imports inevitably had. In 1760, l'Académie des Sciences offered

financial rewards for ideas to boost the flagging industry (Wilkinson

1968: 182). The uniform nature of the French glass on the

Machault may be indicative of the restricted repertoire of

domestic glassmakers.

The heavy styles of English table glass in the first half of the 18th

century had never made much impression on the continental market which

largely fell to Bohemian and German glass; however, in 1745 an excise

tax, levied by weight, was enacted upon English glass manufacture. The

succeeding styles, already inherent in the grandeur and delicate

trumpeting of the English plain stem (Fig. 3), are epitomized in twist

stems (Fig. 4) and in cut glass. The tax caused a reduction in size and

thickness of the vessels and forced the use of ornamentation to make up

for the absence of lustre. Curiously, the result, rarely less than

elegant, was a delightful expression of rococo and the new styles caught

the fancy of continental consumers on a grand scale as Bosc d'Antic's

remarks rather ruefully indicate. An elastic commercial spirit caused

English glassmakers to capitalize on apparently ruinous taxation by

allowing it to force them to meet foreign taste. "All foreign

commissions to be executed to the utmost care and perfection" read a

1757 advertisement in the Whitehall Evening Post (Thorpe

1961: 209).

It is very doubtful that English table glass was less expensive than

French — Bosc d'Antic remarked on its dearness, the lead oxide flux

used was costly, and French stemware far outnumbers English on the

wreck (that is, if English table glass were cheaper as well as

desirable, more of it could be expected). In addition to its

attractiveness, one further attribute may have increased the popularity

of English glass. Lead glass was more durable than thinner and more

brittle non-lead glass, as shown by the relatively better condition of

English glass artifacts after two centuries in the ice and tides of the

Restigouche.

Perhaps as striking as the presence of English table glass is the

presence of a large quantity of stemware of any kind. This is

emphasized by the fact that the Machault was on an emergency mission

to embattled New France, and also by contrast with the yield of table

glass from at least three French forts dating to the 1750s. At Forts

Gaspéreau and Beauséjour, New Brunswick, dating to the first half of

the decade, and at Fort Michilimackinac, Michigan, which was French

until 1761, French table glass was restricted to tumblers, which in most

cases were the pinkish crizzled non-lead glasses (Fig. 1: Thompson 1971:

McNally 1971; Brown 1971).

That a supply of wine glasses was en route to Montreal in 1760 may

point to one or both of two social and economic phenomena. The

availability of table glass to classes other than the very rich was

increasing rapidly in the middle of the 18th century. The few years

between 1760 and the early 1750s may have seen a marked decrease in the

cost of glass, along with an increase in the output of glass factories,

while the middle class was growing. More probably, however, the number

of relatively wealthy individuals in Montreal was very large in

comparison to that in more isolated posts. Excavations at the Fortress

of Louisbourg and at Place Royale in Quebec City recovered considerably

more French table glass than a few tumblers, and included stemware

identical to that found at the Machault wreck (Lafrenière: pers.

com.). Thus a tentative picture of widely disparate economic fortunes

in New France is indicated by preliminary evidence in table glass

research. Such a picture, of course, will surprise no one.

The presence on the Machault of a rather large consignment of

French table glass, not essential for the relief of New France and, for

that period, nearly luxury goods, may also lead to the conclusion that

as late as the spring of 1760 — a time when Quebec City had fallen

and all New France was threatened — there existed a certain amount

of French confidence in the maintenance of French colonies in North

America, either through an improvement in French military fortunes or

diplomatic bargaining at the treaty table (John P. Heisler: pers.

com.).

|