|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 9

Table Glass Excavated at Fort Amherst, Prince Edward Island

by Paul McNally

Interpretation

Ivor Noël Home has pointed out (1969: 27) that glass on American

domestic-colonial sites tends to lag markedly behind the dates commonly

given to styles by collectors and analysts of English glass, but this

argument has never seemed to hold true for 18th-century military sites

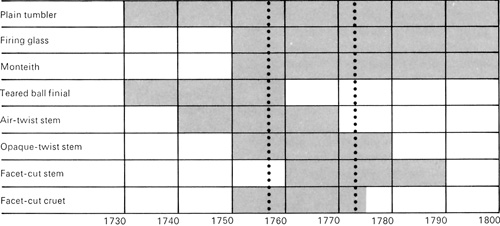

in Canada. Table 1 demonstrates the periods of popularity for each

identified style of table glass found at Fort Amherst, with dates based

largely on standard authorities of English glass. The limits of

occupation at Fort Amherst are indicated by vertical dotted lines.

Clearly, glass styles were in use at Fort Amherst in the period of their

vogue in England.

Table 1. Periods of Popularity for the Identified Styles of Table Glass

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

In addition, the glass found at Fort Amherst must be considered

nothing less than fancy. During the 1760s, English glassmakers were

making undecorated or plain glass, and glass of the sort which has been

discussed was necessarily more expensive. For example, an air-twist

glass cost about 25 per cent more than its plain counterpart, an

opaque-twist glass 40 per cent more than an air-twist, and a facet-cut

glass still more by a quarter than the opaque-twist (Hughes 1956: 99,

111; Elville 1951: 104). The occurrence of such glass is not in itself

surprising since there are precedents on other sites such as Fort

Beauséjour (McNally 1971); however, the table glass from Fort Amherst

seems to present a different view of the use of table glass during this

period than does that from Fort Beauséjour.

The Fort Amherst collection is remarkable, in contrast to the Fort

Beauséjour collection, for the relative frequency of fine tablewares.

Using decorative features, either intrinsic or extrinsic, to make a

categorical distinction between plain and fine wares, it is evident that

at least nine of 16 table glass artifacts represent fine

wares—English filigree and cut glass of some fashionability and

high cost. Without asserting this ratio to be statistically reliable in

so small a sample, it is reasonable to acknowledge a tendency in the

collection toward elegant rather than simple functional wares. In

studying a much larger collection from Fort Beauséjour and applying a

similar distinction between elegant and utilitarian wares on the basis

of decorative attributes, it was found that 77 per cent of the Fort

Beauséjour collection was plain or utilitarian (McNally 1971: 37).

Coupled with the apparently close parallel between deposition dates

of artifacts and dating of styles in England, the elegance of the Fort

Amherst table glass appears to profile a site population who had close

metropolitan ties and who are readily divided into those possessing

little glass and those possessing fine glass; that is, the small

collection suggests that not very much glass was used and, given the

expensiveness of the glass recovered, one is led to the

not-revolutionary conclusion that officers alone used table glass. It is

also possible that some of the table glass was deposited during Duport's

short stay at the site.

Checking these observations with the ceramics found at Fort Amherst

reveals a similar profile of ceramic wares in use — a high

proportion of decorated and expensive pieces including creamware with

over-glaze transfer prints or with low-fired enamel decoration, and high

quality oriental porcelain. Once more, there is considerable contrast

with Fort Beauséjour in terms of the fineness of wares, especially when

the fine wares are represented as a portion of the total ceramics

collection from each site.

The extremity of this contrast is mitigated when the Fortress of

Louisbourg collections of table glass and ceramics are considered. Both

the quality of the fine pieces from Fort Amherst and their relative

quantity approximately duplicate the quality and relative quantity of

fine table glass and ceramics recovered from the Fortress of Louisbourg,

of which the Prince Edward Island fort was an outpost. Fort Beauséjour, during

its first period of British occupation (1755 to 1768), was no less an

outpost of the fortress, but Fort Beauséjour was considerably less

bucolic than Fort Amherst. While the early history of Fort Beauséjour

under British control is characterized by the animosity of Acadian

subjects in the Chignecto region and operations against the French and

Indians, Fort Amherst's history is characterized by nothing so much as

dull routine, broken only by the arrival of provisions in the fall and a

relief garrison in the spring, and by a brief mutiny in 1762 (Hornby

1965). Fort Amherst may also have been easier to supply because there

was a direct sea link between the Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort

Amherst.

It is difficult to conceive that such historical differentiation of

the two forts fully accounts for a rather dramatic contrast between

their table furnishings. Even if Fort Amherst afforded a relatively more

retiring existence than did Fort Beauséjour, it is doubtful that it

afforded greater opportunities for conviviality — there were only

five officers at the fort and they had little contact, social or

otherwise, with other forts. Therefore, a marked difference between

lifestyles at the two forts is not supportable as an explanation for

difference in table glass collections.

As mentioned above, Ivor Noël Hume's observation of anachronisms in

glass styles in use in the colonies does not apply to sites such as

those which have been mentioned in this report. Glass styles on these

sites quite accurately reflect styles in England in the mid-18th

century. They are enlightening, moreover, in that they help to

reconstruct the economic availability and social use of table

furnishings through the period. The contrast drawn between table glass

at Fort Amherst and at Fort Beauséjour, for instance, points up much

more widespread use of glass for utilitarian purposes at the latter site

than at the former, a disparity for which lifestyles at the two forts in

the 1760s can hardly account. The contrast devolves especially from the

occurrence of tumblers at Fort Beauséjour in immense quantities along

with very ordinary stemware. Since plain tumblers, on the basis of

style, must be taken as nearly ubiquitous in time and space through the

second half of the 18th century, it is impossible to establish from

external evidence that they were more used at one time than at another.

But since Fort Beauséjour was re-occupied by the British in 1776 and

again in 1809, while Fort Amherst and the Fortress of Louisbourg

remained essentially unoccupied after 1768, it is possible to conclude,

from the contrast in proportionate representation of fine and

utilitarian wares on the sites, that the availability and use of glass

had expanded greatly by the fourth quarter of the century and had

probably extended much lower on the social scale. Such a conclusion

suggests that the burgeoning of common table glass wares was a

relatively sudden and comprehensive phenomenon during the 1770s and

1780s.

It is argued, then, that the table glass (and, presumably, ceramics)

in use at Fort Beauséjour and Fort Amherst in their concurrent

occupations — up until 1768 — may have been roughly equivalent

at each fort; not numerous and tending toward decorative and elegant

pieces. At Fort Beauséjour the occurrence of plain wares, which are

difficult to date out of archaeological context, apparently sharply

increases during subsequent occupation periods, presenting a

misrepresentative picture of table glass in use during the 1760s. The

Fort Amherst collection, much more discrete in time, may reveal more

truly the nature and quantity of table glass to be found on relatively

unimportant British forts in North America during the Seven Years' War

and immediately after.

|