|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 6

A History of Rocky Mountain House

by Hugh A. Dempsey

Rocky Mountain House, 1866-75

The actual work of constructing the new Rocky Mountain House took

place during the summer of 1866, with Paquet and McCleod in charge of

the crews. The palisades and gates were in place by May; the factor's

house was roofed by June, and work was continued on the men's houses,

the Indian house and the interpreter's house throughout July. In August,

a shortage of food forced a curtailment of building operations while

everyone searched for food. The entry for 24 August, "hard work to keep

ourselves alive,"1 was typical of the month. In the autumn,

supplies were received from Edmonton, and the building work was resumed.

By November, much of the fort was erected and the men were engaged in

gathering stones for the chimneys.

The new Rocky Mountain House was an imposing structure with high

palisades and bastions at each corner. The front gates faced upon the

river while the two-storey factor's house was located against the back

wall. Flanking the square on both sides were long structures housing the

men's quarters, trading room and storage rooms. Scattered through the

compound were the blacksmith's shop and other small buildings, while

adjoining it to the southwest was an enclosure for the garden.

This fort was located "about fifty chains [1,100 yards] downstream

from the old one"2 and was about a mile above the mouth of

the Clearwater.

This was the Rocky Mountain House which became famous in the 20th

century when the chimneys from the chief factor's house were preserved

as a historic landmark. Over the years a romantic aura developed around

this site and many local people believed it to be the only fort site in

the area. The tradition was accepted that this was the fort used by

David Thompson during his explorations, and was visited by Paul Kane and

Captain Palliser. Even the cairn and plaque placed at the site in 1927

by the federal government implied that this was the "original" Rocky

Mountain House. The plaque stated that "David Thompson wintered here in

1800-01, 1801-02, 1806-07, and from here he set out in 1807 for the

discovery of the Columbia River." A plaque giving more accurate

information replaced the old one in 1967. In actual fact, this

particular fort was in active use for less than a decade during the

dying years of the fur trade.

These years were colourful ones, though, for the turbulent Blackfoot

still brought some of their robes and meat to the fort. During this

period, the population of Indians trading at Rocky Mountain House was

estimated to be 300 lodges of Blackfoot, 300 of Bloods, 40 of Peigans,

30 of Sarcees, and 109 of Stonies.3

Campbell Munroe, who lived at Rocky Mountain House during this

period, described a typical trading scene.

The Blackfeet came to the Fort twice a year. They sent two men

ahead to let the people at the Fort know that they were coming. On this

particular occasion, a Blackfoot named Hind Bull and a Blood named

Medicine Owl were the messengers who came a day early to tell the

traders that the Bloods, Blackfoot and Peigans were coming. Their chiefs

were Rainy Chief of the Bloods, Crowfoot of the Blackfoot, and Morning

Plume of the Peigans.

There were four or five families of the Stony Indians camped near

the Fort. John Munroe and the others hid [them] in the basement

of the Fort. On the next day the Blackfeet came, the three chiefs rode

ahead; there were thousands of them.

John Bunn and John Munroe met the chiefs. The first thing that was

asked of the chiefs is to provide four mad-dogs. The mad-dogs were

Indians sworn to protect the Fort. Four were picked out by Crowfoot.

They had war-clubs and circled the outside of the Fort night and day.

The other Indians were asked to camp away from the walls of the Fort,

about fifty yards away. . . .

The chiefs were taken inside and treated with tobacco and other

presents. All the gates were shut and locked, only one narrow door was

used to let the traders go in and out. The door was so narrow that only

one person could pass side ways.... The Hudson Bay men would present the

chiefs with rope tobacco and carrot tobacco; it was considered a great

honor for any Blackfoot to receive this carrot tobacco. The chiefs would

also receive hats with two plumes each, one at the back and one in the

front.

Trading was carried on for three days; when it was over the

mad-dogs escorted the Indians across the River. Then the chiefs departed

from the Fort, leaving behind their best horses as presents to the

Hudson Bay men.4

At other times small groups of Blackfoot came to trade and were

allowed inside the fort. Some were also permitted to stay overnight in

the Indian hall.

Details of trading activities inside the fort also were provided by

William Butler, who visited Rocky Mountain House in 1870.

Within the fort all the preparations have been completed,

communications cut off between the Indian room and the rest of the

buildings; guns placed up in the loft overhead; and men all get ready

for any thing that might turn up; then the outer gate is thrown open;

and a large throng enters the Indian room.

Three or four of the first-comers are now admitted through a

narrow passage into the trading-shop, from the shelves of which most of

the blankets, red cloth, and beads have been removed. . . . The first

Indians admitted hand in their peltries through a wooden grating; and

receive in exchange so many blankets, beads, or strouds. Out they go to

the large hall where their comrades are anxiously awaiting their turn,

and in rush another batch, and the doors are locked again. . . . So the

trade progresses, until at last all the peltries and provisions have

changed hands, and there is nothing more to be

traded.5

The first person to record visiting the new fort after its completion

was the Reverend John McDougall. He arrived there in February, 1869, and

found Chief Trader James Hackland in charge. He observed that the fort

"had been thoroughly rebuilt, and was now a large place in regular fort

style, with stockade, bastions and citadel."6

At this time the trade was brisk, largely because of the number of

skirmishes between the Blackfoot and Americans in Montana. As a result,

the factor at Edmonton House was able to report on 5 December 1869 that

"A great many Indians had been in on a Trade at the R[ocky] Mo[untain]

House. Most of the American Indians being at war on the other side, come

to this side to trade. Trade pretty good, but very expensive, Indians

troublesome & great beggars."7

But even the trade on the North Saskatchewan was no longer

exclusively that of the Hudson's Bay Company, for free traders were

beginning to come in from Red River. It was common knowledge that

negotiations were under way for the transfer of the western territories

from the jurisdiction of the Hudson's Bay Company to that of the

Canadian government. This left the Hudson's Bay Company without its

legal powers to control the trade, and freemen from Red River colony

were quick to take advantage of the situation.

In the fall of 1869, a small trading party led by two Red River men

settled near Edmonton House with a supply of goods. In February, 1870,

Thomas Bird and James Gibbons bought them out and took three dog teams

of goods to Rocky Mountain House. "My goods were rum, powder, shot, and

some dry goods and trinkets," recalled Gibbons.8 When they

arrived at the Hudson's Bay Company fort they were refused admittance,

but the rum provided them with a means of approaching a smallpox-ridden

Blackfoot camp in the area. By the time they finished trading, they had

obtained 108 buffalo robes and 9 horses for one keg of rum.

This was a prelude to the kind of trading tactics which the Blackfoot

could expect, for Americans were also beginning to take advantage of the

weak legal position of the Hudson's Bay Company. In December, 1869, a

small party of Montana traders led by Alfred Hamilton and John Healy

penetrated the heart of the Blackfoot hunting grounds in southern

Alberta and built Fort Whoop-Up near the present city of Lethbridge. As

whiskey was an important item of trade, they soon cut into the volume of

rum-free trade carried on at Rocky Mountain House.

In February, 1870, Father Lacombe paid a return visit to Rocky

Mountain House and then came again in November to spend the winter. On

the latter trip he was accompanied by Father Constantine Scollen, and

the two men spent fruitful weeks collecting and revising notes for a

Cree grammar and dictionary.9 While the priests were there,

Captain William Butler arrived for a brief visit. Butler noted that the

fort "is perhaps the most singular specimen of an Indian trading post to

be found in the wide territory of the Hudson's Bay Company. Every

precaution known to the traders has been put in force to prevent the

possibility of surprise during 'a trade'. Bars and bolts and places to

fire down at the Indians who are trading abound in every direction; so

dreaded is the name borne by the Blackfeet, that it is thus their

trading post has been constructed."10

The warlike reputation of the Blackfoot figured prominently in a

number of deputations given in Montana in 1870 during an investigation

of horse-stealing activities. According to a prospector, John Newbert he

was at Rocky Mountain House in 1869 when a party of Blackfoot brought in

horses bearing Montana and United States military brands. "I also saw an

Indian, a Blackfoot," he swore, "who bragged that he had killed twelve

white men. . . . The Indians invariably stated and bragged to me that

they had stolen [horses] from U.S. citizens."11

The statement of Newbert, as well as those of other miners who had

visited Rocky Mountain House, soon created an international issue that

was the subject of correspondence between the United States, Great

Britain and Canada. The Americans claimed that Rocky Mountain House was

a source of ammunition for the Blackfoot tribes and was a centre for

trading off horses stolen in the United States. The Hudson's Bay

Company, on the other hand, claimed that American weapons had turned the

Blackfoot into dangerous customers. "Every other Blackfoot who trades at

the Rocky Mountain House now has a revolver in his belt," stated

Christie, "and in our trade with them our Lives are often in great

danger. They generally visit our Fort in large bands, and are very

troublesome."12 He also added that Hackland, the clerk,

"would not encourage or ask these Indians to bring American horses to

him, or trade them knowing them to be the property of the American

Government or American Citizens."13 Then he concluded with

the innocent comment that "Rocky Mountain House was established for the

benefit of the Assiniboine or Stone Indians, peaceable and harmless

Indians, who hunt along the mountains, also with the view to keep the

Blackfeet away from Edmonton House (the Head Quarters of the

Saskatchewan District)."14

By early in 1872, John Bunn was in charge of Rocky Mountain House and

although some Blackfoot parties came in, the trade was not brisk. His

returns for the 1871-72 season included only 437 buffalo robes, 490

beaver, 95 marten, 70 bear, and lesser numbers of other

skins.15 Much of this trade had come from the local Stony

Indians while the Americans, who were operating illicit forts on the

Belly, Highwood and Bow rivers, were cornering most of the Blackfoot

trade.

In an effort to get more business, the Company kept Rocky Mountain

House open throughout 1872, but by August, Bunn reported that "no

Indians have been in worth talking about all Summer, so that the folks

up here have had nothing to do but to eat up the fruits of last year's

trade."16

By this time, the lawlessness accompanying the illicit trade in

southern Alberta had reached government circles in Ottawa. Accordingly,

Colonel P. Robertson-Ross, Adjutant-General of the Militia of Canada,

was sent out to study the need for military protection. He arrived at

Rocky Mountain House in September, 1872, just as a few Blackfoot parties

were beginning to arrive. A French Canadian named Jean l'Heureux who

lived with these Indians had prepared a map and census of the tribes and

this was shown to the government official.17 This l'Heureux

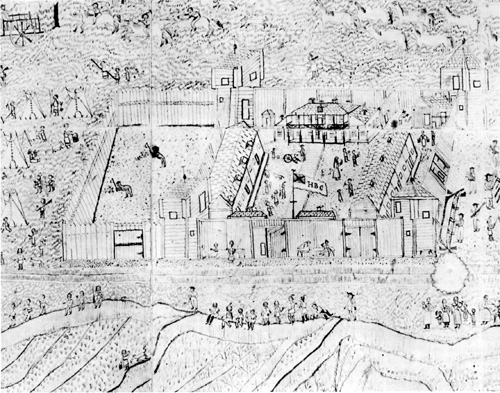

was the same man who, a year later, made a remarkable drawing of Rocky

Mountain House. Authenticated by the results of the 1966 archaeological

excavation, the sketch shows the precise location of buildings, as well

as activities around the fort. L'Heureux gave the drawing to Sir Sanford

Fleming, a Canadian Pacific Railway surveyor, in 1874, and it eventually

was deposited in a library in Pittsburg.18

Robertson-Ross obtained some useful information at the fort,

including the location of American whiskey forts on Canadian soil.

Largely on the basis of the colonels findings, the North-West Mounted

Police was formed a year later.

Rocky Mountain House was open during the winter of 1872-73, but the

new clerk in charge, John Sinclair, felt it was a losing business. He

became exasperated with the local Stony tribes and thought they were

"the damest of Indians ever I came across. The Mountain Fort is just

kept up to feed the Stonies with."19 He observed that there

were "Americans within two days Ride from this place with Licquor, so I

think their will be no trade at all at this place."20 He

concluded his report with an appeal for books "to pass away dull times,

for this place was not meant for me, its only fit for an Animal. It

appears that the Indians wants this place to be shifted to the Porcupine

Tail21 or some place at the Red Deers

River."22

As the winter progressed, his predictions were confirmed and by the

end of 1872, only 242 buffalo robes had been traded from the Blackfoot;

of these, 52 had to be given away to destitute Stony Indians. The

remainder of the half-yearly trade was equally as bad, with only 382

beaver, 72 bear and 26 marten being obtained.23

The west had been changing rapidly since it had been taken over by

the Canadian government in 1870. Under a provision of the transfer

agreement, even the Hudson's Bay Company's legal claims to its trading

posts had to be established. Accordingly, in January, 1873, a surveyor

named W.S. Gore arrived to measure the Rocky Mountain House claims. His

survey included "500 acres fronting on the North bank of the

Saskatchewan River, valueless for farming purposes, being a mossy swamp

covered with Spruce and Tamarac. However. . .a few acres surrounding the

Fort are good."24

4 Detail of fort from sketch by Jean l'Heureux, 1873

(Photo in

Glenbow-Alberta Institute).

|

He did not show the fort in detail in his plans, but merely indicated

a structure about 175 feet square with bastions on each corner and a

garden on the southwest side. He commented that the fort "is new and

substantially built but there is very little trading done there now, the

'Blackfeet' finding a market nearer their hunting

grounds."25

During the remainder of the winter of 1872-73, the trade continued to

deteriorate, with even the faithful Stony Indians going to the

Americans.26 However, the post was kept open for another

summer, with Angus Fraser being left in charge. By fall, he had taken in

248 buffalo robes, 136 beaver, and a few other pelts.27

In September, 1873, Alfred R.C. Selwyn of the Geological Survey of

Canada visited the fort and noted that "barley, potatoes, turnips, and

onions were being grown successfully."28 He had come overland

from Edmonton and in order to reach the fort he had to go about a

quarter of a mile above the mouth of the Clearwater River. There he

probably used the old crossing which had been associated with the

earlier forts.

The trade did not improve during the winter of 1873-74 so, in

desperation, John Sinclair led an expedition out to the plains in March,

1874, in search of food and to trade with the Indians. He came back with

only 40 buffalo robes and commented that there were "too many free

Traders out amongst them and all well supplied with goods &

Liquor."29 He also had visited Dave McDougall, brother of the

Methodist missionary, who was trading on the Bow River, and noted that

he had "no person to oppose him; they have all the trade to

themselves."30 Not far away, he met a whiskey trader who had

taken 6,000 buffalo robes during the winter.

The diminishing returns, combined with McDougall's proof that the

plains were no longer a dangerous territory, sealed the fate of Rocky

Mountain House. At a meeting of the Northern Council of the Hudson's Bay

Company in July, 1874, a resolution was approved "that in consequence of

the Indians having ceased to frequent the country in the vicinity of the

Rocky Mountain House, the establishment at that post be reduced to 2

men, for the purpose of looking after it, and that a small supply of

goods be furnished them for Trade, in the event of any Indians visiting

the fort."31 Angus Fraser was sent back to the fort in the

fall while plans were made to re-enter the Bow River country for the

first time since the abandonment of Peagan Post in 1834. Early in

October, John Bunn was transferred from his post near Victoria Mission

and set out for the new Methodist mission station of the Reverend John

McDougall near the confluence of the Bow and Ghost rivers. As soon as he

had set up a temporary trading camp there, he reported that "A few

Blackfeet have been in who report that most of them have gone to Belly

river to trade but that a good many intend coming in

here."32

At the time Bunn was writing his report, the North-West Mounted

Police had marched across the western plains and were building Fort

Macleod on the Oldman River. Within a matter of weeks most of the

illicit whiskey trade was stopped and any danger of Blackfoot aggression

was past.

In the meantime, Fraser continued to maintain Rocky Mountain House

during the winter of 1874-75. Shortly after his small supply of trade

goods was received in October, 1874, a party of Sarcees arrived with

2,500 pounds of dried meat, 200 pounds of pounded meat, and 78 buffalo

robes. He also had promises from the Stony Indians that they would trade

with him,33 but by spring, he needed only a small

bateau to bring the returns downstream to Edmonton.

By this time, plans for the abandonment of Rocky Mountain House had

been completed. During the winter, Hudson's Bay Company Commissioner

J.A. Grahame observed that "the Post at the Rocky Mountain House has

been a grevous expense to us & as you acknowledge, its Returns are

of no importance. If no improvement is exhibited this winter you will at

once close it up, endeavouring to find some one you can depend upon to

take charge of it. . . . The question of the removal of the Rocky

Mountain House Buildings to Fort Pitt has been discussed but I have not

yet had your final opinion upon the expense thereby likely to be

incurred and have to request you to furnish it by first

opportunity."34

In accordance with the commissioner's instructions to find someone to

look after the buildings, Hardisty offered to advance food and trade

goods to Angus Fraser in the spring of 1875 if he would stay at the fort

at his own expense. Fraser accepted and the arrangements were approved

by the commissioner "provided you are certain of recovering the advances

you have made [and] I presume your agreement with him gives you the

control of any Furs he may collect."35

Although Fraser was now a free trader, he reported to Hardisty on the

situation there in November, 1875. "Some of the Stonees Broke open one

of the Store Windows this summer and stold grease, Robes and leather,"

he stated. "And they left the window open and the dogs got In and eate

up all the grease, Robes, leather and old Harness about the

place."36 By this time, the fort was only a pitiful reminder

of its glorious past and Fraser sadly observed that "I have three of the

old dogs Here, all the rest are stolen or dead."37

A few Stony Indians came to the fort and Fraser succeeded in getting

78 beaver skins, 46 marten, one fisher, 3 lynx, one mink, 8 muskrats,

142 antelope skins, 15 buffalo robes, 26 buffalo skins, 28 moose skins,

and 7 bear skins.38

Fraser may have stayed at the fort during the next winter of 1875-76,

to act as caretaker while the dismantling of the buildings was being

considered; however, by the fall of 1876 he was in charge of a small

post on the Ghost River for the Hudson's Bay Company.

The fate of the buildings at Rocky Mountain House cannot be

determined from available records. In January, 1876, Hardisty was told

that "If the cost of taking down to Fort Pitt one of the Buildings at

the Rocky Mountain House would not exceed $200.00, I think it would be

advisable to make the attempt, leaving the others for the

present."39

Although there is no evidence that any action was taken, the fact

that these instructions came from the commissioner makes it seem likely

that the building was moved. The only other official mention of the

buildings came in June, 1877, when Lawrence Clarke wrote to Hardisty,

saying "I am instructed by the Chief Commissioner to ask you to be

prepared at the meeting of ensuing Council at Carlton to lay before him

an estimate of cost of removing store at Rocky Mountain House and

rafting same to Carlton."40 Again, there is no direct

evidence to indicate whether the move was ever made.

In the summer of 1882, A.D. Patton and J. Murphy visited Rocky

Mountain House and said it was "still in a good state of

preservation."41 They also observed that "A large amount of

lumber is piled on the bank as if intended for transportation down the

river,"42 but did not say that the lumber was actually from

the fort itself.

In 1886, J.B. Tyrrell of the Geological Survey of Canada took a

photograph of the site; it showed only two bastions, a small cabin and

four chimneys still standing. In his report, Tyrrell noted simply that

"Rocky Mountain House, the ruins of an old fort of the Hudson's Bay

Company, is situated in an alluvial grassy flat bounded on the south and

east by the river and on the north and west by dense forests and

swamps."43

And so ended Rocky Mountain House. Built when the transmountain

country was still unkown and closed during the dying years of the fur

trade, it had 76 precarious years of existence. As a Kootenay post it

was a failure; as a Blackfoot post it was a success; and as a historic

site it figured prominently in many events relating to the development

of western Canada.

|