|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 26

Analysis of Animal Remains from the Old Fort Point Site, Northern Alberta

by Anne Meachem Rick

Discussion and Conclusions

Bones of most of the larger fish species occurring in Lake Athabasca

were found among the faunal remains. Walleye and pike were the most

abundant species, both in number of bones and MNI; these are fish of

fairly shallow water habitat and can be caught during most months of the

year. The whitefish, staple food of fur-trade wintering posts, here

ranks only third in numbers of individuals, but whitefish bones are

fragile and they may not have survived as well as those of walleye and

pike. Grayling. Thymallus arcticus, and goldeye, Hiodon

alosoides, were not found although both are good-sized, edible fish

occurring in the delta area at the west end of Lake Athabasca (Scott and

Crossman 1973: 302 map, 328 map).

The Peace-Athabasca delta, just a few miles west of Old Fort Point,

is an area extremely rich in waterfowl, particularly during spring and

fall when many species migrate through the area: thus it is interesting

that so few waterfowl bones were found at the site. If the site is

assumed to be Fort Wedderburn II, then this paucity becomes more

understandable, for the occupants would have been there after the major

flights of migrating birds had passed southward in fall and before

spring migration began in earnest. The presence of grouse and ptarmigan

in the faunal remains indicates that these edible birds were hunted as

well as the larger aquatic species. Probably all birds found at the site

were used for food although the trumpeter swan was valued for its skin

as well as its flesh and goose skins were also occasional trade items at

the fur posts.

Among the mammals, all three large ungulates which ranged through

this region — caribou, moose and bison — were found at this

site. Only two varying hares occur although this species was often a

major food item at posts. Four furbearers — beaver, Arctic fox, red

fox and otter — were definitely identified and as many as seven

(adding the unidentified mustelid, wolf and possibly coyote) might have

been present. Of this group only beaver and otter were valued highly for

meat as well as fur; however, during periods of food scarcity almost any

kind of meat was eaten. Thus the furbearers found here could have been

food items, animals trapped near the site and brought into camp to be

skinned, or both.

Of domestic animals, the dog was almost certainly present despite the

fact that no single canid fragment could be identified unequivocally as

this species. The dogs at Fort Wedderburn I were probably taken along in

the move to Fort Wedderburn II. No domestic ungulates such as horse,

cow, sheep or pig were recorded from the faunal material and this is in

keeping with the proposed 1817-18 date for the site. Perhaps the first

ungulate introduced to this area was the horse; one was known to have

been at Fort Wedderburn in 1820-21, after the fort had been moved back

to its original location (Krause 1976: 33), and Innis (1970: 295) notes

that the journal of 1823-24 mentions horses in use at Fort Chipewyan.

Few general conclusions can be made about butchering or cooking at

this site because of the small size of the sample. Fish, birds and some

mammals probably were brought to the site whole, since skeletal elements

from various parts of the body were present in many cases. Large mammals

could have been brought in as sections or entire animals. Beaver, Arctic

fox, red fox and otter are represented by major body bones indicating

that some furbearers arrived at the fort as whole animals rather than as

skins. Cut marks were found on bones of pike, swan, goose, hare, beaver,

moose, caribou and bison and seem to be primarily butchering marks,

although some of the cuts on bird bones may have been made during

removal of meat after cooking. The only clear example of a skinning cut

is a beaver distal tibia fragment showing marks where the pelt was cut

away. Not many bones were burned: several pike and walleye bones, a

single unidentified bird femur, a beaver tibia, three red fox bones and

some fragmentary unidentified mammal bones. Burning does not necessarily

indicate cooking; it could result from deliberate disposal of bones in a

fire or chance burning of bone refuse.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the site occupation was brief,

and this in itself could account for so few animal remains being found.

Another reason for the scarcity of bones at Old Fort Point may be the

presence there of dogs. Dogs are efficient bone destroyers and can chew

up some bones to the point where they leave no archaeological trace.

Many of the fish, bird and mammal bones from the site bore tooth marks

and other indications of gnawing by large carnivores, probably dogs.

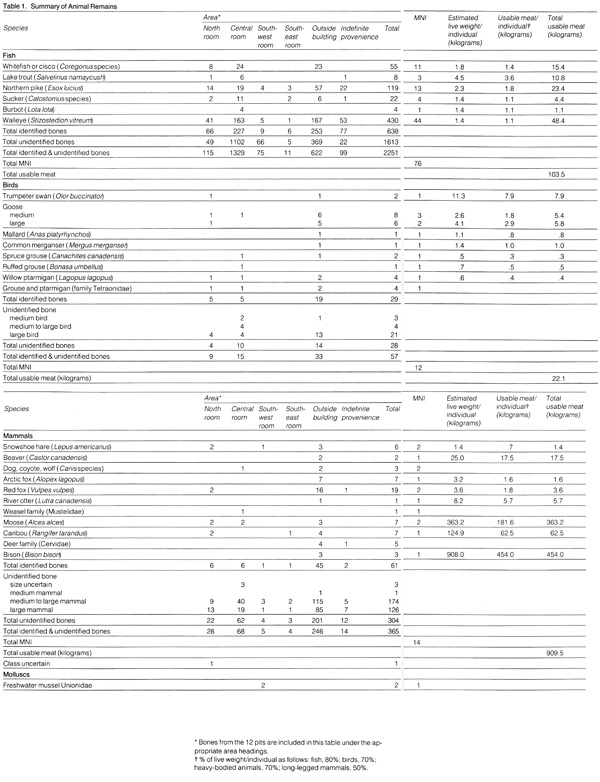

Calculations of usable meat (based on MNI) provided by species which

may have served as food are useful at localities where large numbers of

individuals have been identified but are of doubtful value at a small

site such as Old Fort Point where the presence of one or a few large

animals can distort the results. Nevertheless, these calculations have

been made and are included in Table 1. A total of 1035.1 kg of edible

meat is estimated from the faunal remains, divided among the vertebrate

classes as follows: fish, 103.5 kg (10%); birds, 22.1 kg (2%), and

mammals, 909.5 kg (88%). The single bison accounts for nearly half of

the total usable meat at this site and mammals seem to have provided a

much larger proportion of meat than did fish. However, keeping in mind

that many fish bones were discarded by the archaeologists because of

their poor condition and that perhaps only part of a bison might have

been brought back to the fort rather than an entire animal, fish may

actually have played a much larger part in the economy than indicated by

the bone remains analyzed. In addition, the figures for kilograms of

usable meat per individual are averages which do not take into account

large individuals, particularly important in the case of fish where the

adult size range is extensive. Birds provided only a small amount of

meat in comparison with fish and mammals.

Note that no weight and usable meat estimates are given in Table 1

for the two individuals classed as Tetraonidae and Mustelidae or the two

Canis individuals. Since these animals cannot be accurately

identified, one can only guess at their average weights. However, the

bird would have supplied less than .5 kg of meat, the mustelid probably

less than 1 kg and each Canis probably somewhere between 25 and 50 kg.

Percentages of edible meat provided by the three classes would change

only slightly if these figures were added to the totals in Table 1.

(click on image for PDF version.

Table 2 gives bone numbers and weights for the different vertebrate

classes and is included to aid comparison of these data with those from

other sites in which bone numbers and weights have been stressed as

analytic tools. While both these types of information are useful, many

adjustments must be made to raw data before they can be compared, in

order to reflect natural differences between classes in number of

skeletal elements and skeletal weight.

|

| Table 2. Bone Numbers, Weights and Percentages by Class |

|

| Class | Number |

Percentage

of total

number |

Weight

(grams) |

Percentage

of total

weight |

|

| Mammal | 365 | 13.6 | 5410.8 | 86.7 |

|

| Bird | 57 | 2.1 | 121.8 | 1.9 |

|

| Fish | 2251 | 84.1 | 707.5 | 11.3 |

|

| Class uncertain | 1 | <0.1 | 0.1 | <0.1 |

|

| 2674 | 99.8 | 6240.2 | 99.9 |

|

Depositional patterns in the faunal material are unclear. Many bones

could have been thrown over the nearby scarp and thus lost to

archaeologists. Site erosion caused movement of artifacts downslope

toward the northwest. Although an attempt was made to fit together

broken bones, only one crossmend could be made, and that between two

fragments of a large goose humerus found in the sub-floor pit in the

north room and in the northwest pit. This seems to indicate that bones,

too, eroded out in a northwesterly direction. In general, bones occur

inside the building and outside to the north and west (the direction of

the down-slope). The north and central rooms contained moderate amounts

of fish, bird and mammal bones, while the southeast and southwest rooms

contained lesser amounts of fish bone, no bird bones and only a few

mammal bones. Even when the two south rooms are considered together

(each is only one-half the size of the other rooms) they contain little

bone compared to the north and central rooms.

Twelve pits (Fig. 1, Table 3) are present, five within the building

in the north, central and southeast rooms and seven outside to the east,

north and west. The three pits east of the building are devoid of animal

bones and four of the inside pits (in the central and southeast rooms)

have no bones or only a very few. Of all the inside pits, only the

sub-floor pit in the north room contained a significant quantity of

faunal remains. Eighty-six fragments representing five fish species

(whitefish, lake trout, pike, sucker and walleye), swan, medium and

large goose, hare, unidentified large bird and mammal and a bone of

uncertain class were found there. The southernmost of the southwest pits

held three moose vertebrae but no other bones. The north pit outside the

building contained 103 bones among which were whitefish, pike, walleye,

ptarmigan, Tetraonidae, hare, red fox and unidentified medium to large

and large mammal bones. The northwest exterior pit held 119 bones

including whitefish, pike, walleye, merganser, Tetraonidae, medium and

large goose, Canis sp. (wolf?), otter, Arctic fox and some

unidentifiable medium to large and large mammal pieces. The northernmost

of the southwest pits contained 435 fragments, mostly fish (whitefish,

pike, sucker and walleye), as well as one ptarmigan bone, medium and

large bird fragments, a bison vertebral spine and numerous fragments

from medium to large mammals. Fish, bird and mammal bones are

represented in the pits in approximately the same proportions in which

they occur over the whole site, although the sub-floor pit in the north

room contains nearly as many bird as mammal bones. While some pits may

contain bones secondarily deposited by erosion, the relatively large

quantities of bone in four pits may indicate that those pits served some

sort of storage or disposal function.

|

| Table 3. Animal Remains from Pits |

|

| Pit designation | Fish |

Bird | Mammal |

Class

uncertain | Total |

|

| Outside pits |

|

| North | 73 | 2 | 28 | 0 | 103 |

|

| Northwest | 80 | 8 | 31 | 0 | 119 |

|

| North-southwest | 340 | 3 | 92 | 0 | 435 |

|

| South-southwest | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

|

| Northeast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| North-southeast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| South-southeast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| Inside sub-floor pits |

|

| North room | 74 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 86 |

|

| Central room |

| Eastend | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Centre | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Southwest corner | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Information on the season during which this site was occupied was

important in determining its identity. Historical and archaeological

evidence pointed toward the site being Fort Wedderburn II, but was not

conclusive. The faunal analysis, while not proving that this is indeed

the fort site, is in accord with this identification. The fish at the

site could have been caught in most seasons; fish were taken throughout

the year at Lake Athabasca outposts although fishing was poor in summer

and the major part of the catch was collected in late fall and early

winter. Most of the mammals yield no information on seasonality since

they could be caught year-round; however, furbearers were more likely to

have been taken during winter when their fur was prime. No bones of

young birds or mammals were found, thus providing no evidence for summer

occupation although not denying it. In contrast, the presence of Arctic

fox and willow ptarmigan remains indicates occupation during the cold

season. The Arctic fox's range is usually farther north than Lake

Athabasca but some animals occasionally wander south during fall and

winter. Willow ptarmigan breed on the tundra, migrating south to the

forest in October and November and returning north in April. Both these

species would have had to be taken during the period October to April,

the approximate time during which Fort Wedderburn II existed. Spruce and

ruffed grouse are resident in the area all year. Swans, geese and ducks

would have been in the region during spring, summer and fall; the large

goose bones may represent migrant forms occurring in the area during

spring and fall or perhaps late summer and fall only. Possibly the

scarcity of bird bones is an indication that the site was not in use

during the late spring, summer or early fall when waterfowl would have

been abundant and easily obtained.

|

|

|

|