|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 20

Ranch Houses of the Alberta Foothills

by L. G. Thomas

Ranch Houses of the Alberta Foothills

An increasing interest in the social history of the Canadian West

gives a significance to the domesticities of the region's early settlers

that might a generation earlier have been dismissed by the scholar

as totally irrelevant or at most merely amusing or picturesque. In

spite of diligent collecting by institutions, groups and individuals,

the number of adequately authenticated artifacts is comparatively small.

There has been little written on their provenance or their relationship

to one another in their daily use, and farm and ranch houses, even some

built as late as the early 1920s, have in many cases perished or, more

often, fallen into ruin or disuse. Even where there has been an

intelligent and careful attempt to recreate the setting of a pioneer

room, the product often seems to the observing eye, no matter how

sympathetic or perceptive, sadly unconvincing as a means of transmitting

historical knowledge to the beholder. It may be that the weakness of

the exhibit arises not from the use of the wrong materials, but from an

absence of information about the social history of the period and

locality portrayed. The contriver of the exhibit is certainly not to be

blamed it his tableau fails to come alive; the onus rests on the

historian who has failed to record and even more to interpret the past

in a way that conveys to his audience the kind of sensitivity to the

implications of a piece of china or the hang of a curtain that converts

an object into a visual, emotional and intellectual excursion into the

past.

Recent studies have begun to illuminate and indeed to reinterpret

the past of the ranching community in southern Alberta. They view it as

an experience that, although related to large-scale stock raising in

North America and indeed in the world at large, was at the same time

uniquely Canadian, significant not only for the locality but also for

the region and for the nation. The uniqueness of the ranching community

in terms of its economic and governmental relationships has been

convincingly demonstrated; the impact of these relationships upon the

social development of southern Alberta has been less fully

explored. In such an exploration, the houses in which the ranchers

lived, the way they were equipped and the way they functioned in

relation to the ranch buildings and to the world outside are all

relevant.

This paper, the reader should be warned, is very much the product of

the personal experience of the writer. He grew up in the Alberta

foothills in the years between the wars, in a district that lay on the

northern fringe of the ranching country not very far, even by team or on

horseback, from the urban influences of Calgary, which were felt in this

area as early as the 1880s. The nearest town was Okotoks (previously

known as Sheep Creek and, briefly, as Dewdney) on the north side of

Sheep Creek. Most of the families who settled along the north side of

the valley of Sheep Creek before 1914 called themselves ranchers though

they were really small stockmen. The overwhelming majority were of

United Kingdom origin though a few well-connected families from

continental Europe contributed a cosmopolitan note and fitted easily and

creatively into the life of the valley. An even more overwhelming

majority shared a passionate addiction to horses, and polo, racing and

the gymkhana lingered even after the war of 1914-18 dealt its shattering

blow to the polite society of the Alberta foothills, if such a society

ever existed. The majority of the prewar arrivals had at least a

sentimental attachment to the Millarville church. Christ Church,

uniquely built of vertical logs, survives as the most important

architectural relic of the community's past.

Cottonwoods, the house in which the author was born, was built in the

early 1890s by the Austins, one of the relatively few Eastern Canadian

families to settle as early as this and as far west of Okotoks. George

Frederick Austin, a retired surveyor, probably from the Ottawa valley,

came to homestead in 1885, accompanied by his much younger wife, the

intensely musical daughter of a clergyman, and his son, Edmund. The

house they built is reported to be the earliest frame house, as distinct

from a log house, to be built in this part of the foothills. The site of

the original log house, slightly to the west of the existing frame

house, may still be distinguished. It was burned about 1910 as a

sanitary precaution; it was infested by bedbugs. The site successfully

resisted the archaeological fumblings of a young boy inspired by the

exploits of Dr. Schliemann of Troy.

The frame house, originally consisting of two ground-floor rooms each

about 16 feet square, with bedrooms above, is T-shaped and each part has

a steeply sloping roof (Fig. 1). It is believed to have been built in

two stages, with the kitchen that forms the stem of the T added to the

original living room, now the dining room of the house. The stairs rise

steeply from the latter room, and the locations of the outside entrance

to the cellar and of a trap door, long unused, in the dining room floor

suggest that this room and the bedrooms above formed the dwelling unit

for the family at least for a short time. The difference in interior

finishing of the two bedrooms above the dining room and the two above

the kitchen also suggests that the house was built in two stages as the

latter (and presumably later) are almost entirely finished in

conventional lath and plaster and milled lumber like the two downstairs

rooms, while the inside walls of the former and the doors into them are

of wide plank. The two bedrooms over the kitchen (though not the door to

the fairly large linen closet that, except for a landing or corridor,

occupies the rest of this floor-space) have conventional doors and

locks rather than latches.

1 Cottonwoods circa 1911. My father had completed his additions, but

little had been done to the garden except for a rudimentary fence. The

horns, possibly antelope, were a popular form of ornament.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

The doors on the ground floor differ in style and though some of

these have been moved from their position of 1910 when the house passed

from the possession of the original owners to that of the writer's

family, this seems to confirm that the house was built in stages.

The chimney, most of its original brick still intact, is of a

yellowish-brown brick, quite unlike the red brick made not far away at

Sandstone, just west of Okotoks. (It reminds the writer of the brick of

old houses in Calgary and indeed, subject to confirmation, of the brick

used by W.R. Hull to build the substantial ranch house on Fish Creek,

east of Midnapore, which later passed into the possession of Patrick

Burns and was more recently extended and restored by the latter's

great-nephew, Richard Burns.) The chimney runs up the south wall of the

kitchen, the common wall between the two original rooms. If the kitchen

were built later than the dining room, the chimney, if built as part of

the first unit, must have been on an outside wall. This may seem

unlikely as the chimney is not brick-built to ground level, but rests on

a timber frame. The latter opens to the kitchen and, with a shelf

half-way up and just behind the kitchen stove, still forms a convenient

airing-cupboard. A door out of the kitchen into a small pantry under

the stairs presents a puzzle as it is of the same plank construction as

doors in the bedrooms above the dining room. In 1910 the cellar steps

were reached by a trap door in the middle of the kitchen floor. They

were moved to the pantry in the interests of safety. If the door to the

pantry were put in while the first section was in use as a dwelling, it

would have served little purpose and caused a draught formidable even to

hardier and more youthful pioneers than the original owners of

Cottonwoods.

The T-shaped floor plan, steeply pitched roof and frame construction

are common on the prairies not only of western Canada but also of the

United States and, for the late 19th and early 20th centuries, might

almost be called "typical." The house is also evocative of those built

in the later 19th century in the Ottawa valley, with which the Austin

family had associations, Its outlines are perhaps less grimly Gothic and

more comfortably Georgian than is characteristic of the style, but this

impression may be due to the setting in what has become a grove of tall

trees, most of them Russian poplar planted about 1930. Certainly the

earliest snapshots suggest a bleaker line.

The impression may also owe something to the later additions (Figs.

1-4). These, a sitting room (the term commonly used by most of the Sheep

Creek settlers, "drawing room" being too pretentious and "lounge" not

having achieved its later vogue in the United Kingdom), an adjoining sun

porch, an entrance porch, a verandah, at first open but later screened,

and a "toy house," now used for storage, on the north, were added to

provide additional amenities. Most of these assumed their present form

as the result of alterations in 1928-29 when the sitting room and sun

porch were added though the "toy house" and the porches at the front

(south) and back (east) doors were built in 1910 when the property

changed hands. Though the porches also served as cloakrooms and as

storage space for indoor and outdoor tools and for the tennis net and

racquets, their primary function was to protect the inner doors and

those who used them against the weather. The small verandah was added

about 1912 to provide a protected outdoor play-space.

2 Cottonwoods from the southeast, circa 1915. By this time the

verandah had been added and the hops had begun to assert

themselves.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

3 The verandah on the southeast of Cottonwoods, circa 1916. The

butter-making equipment is believed to have been brought by the

previous owners from Ontario in 1885.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

4 Siding and corner details of the southeast angle of Cottonwoods,

circa 1916. The plant is probably a Scarlet Lynchis, known to us

as "Mrs. Scott's plant."

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

The effect of these alterations and additions was to give Cottonwoods

a distinctive character (Figs. 6, 7). This arises, in the writer's view,

from the way in which the roof lines of the additions echo the line of

the roofs of the original T and the shed roof of the sun porch and

sitting room. This was, I am confident, a fortuitous rather than a

contrived effect. The basic pressure for the additions came from my

mother who knew what she wanted and undoubtedly, if the success of her

room arrangements is a criterion, had an eye for the relationship of

shapes as well as for colour and texture. Though she sketched in pen and

pencil and painted a little in watercolours and in oils, it would not

have occurred to her that her talents would extend to producing

builders' drawings. The work was executed wholly by my father and his

bachelor partner, both with some training in civil engineering in

England. The partner was much more interested in carpentry than my

father, who was essentially a horseman. Whatever the source of the

design, it may be properly designated as vernacular architecture. Indeed

it would be difficult to think of any foothills buildings of this period

that owe much to formal training in architectural theory or practice

though many were enriched by skilled craftsmanship. This is not to say

that the buildings, however simple in construction and primitive in

material, owed nothing to architectural tradition or to eyes insensibly

trained by looking at the architectural heritage of older societies.

5 Cottonwoods and grounds from the south, 1917. The limed line in the

foreground marks the eddge of the tennis court.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

6 Cottonwoods from the southeast, circa 1919. The hops are now

well-established. The water barrels provided a supply of rainwater as

the well water was very hard.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

7 Cottonwoods circa 1935. The sitting room and sun porch had been added

circa 1928-29 and the windbreaks planted at that time had made some

growth.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

The original house and the additions were all built not on stone or

concrete foundations, but on wooden sills resting on the rocks and

boulders plentiful so near a creekbed. The house, after as much as 80

years, still appears to be sound and is easily heated; it has long

enjoyed the reputation of being warm in winter and cool in summer.

Electric power and propane central heating were installed recently

without major alteration to the structure and the two original

cellar-holes are still in use for storage. On the hill behind the house,

excavations, presumably for root cellars, may still be seen, but these

have not existed within present memory though quite commonly used

elsewhere in the district and throughout the ranching country of the

foothills.

Water supply has never been a problem as, apart from Sheep Creek,

there are flowing springs in the vicinity and water is reached in the

gravel of the valley by digging a few feet from the surface. The gravel

also provides excellent drainage. Water has never been piped in for

domestic use, but for a time a pump in the kitchen provided water for

the sinks and for the washbasin and tub in the adjacent bathroom, made

in 1928 by partitioning off part of the kitchen. The water from the well

this pump served was slightly sulphurous to the taste, a not uncommon

phenomenon in a location so close to the pioneer oil field at Turner

Valley, and sweeter water is now pumped from a well outside the kitchen

door, not more than ten yards away. An earth-closet, not the original,

is still in service.

Little of the original siding has been replaced and a number of the

original window frames and four-paned sashes survive where least exposed

to the action of the weather and the fumes from Turner Valley. It is

said that the soundness and durability of the structure owed much to the

fact that the Austins had the materials on hand for at least a year

before they began construction and the wood was thus thoroughly

seasoned. The wood probably came from Okotoks, eight miles by road to

the east, where the Lineham lumbermill was the major pioneer

enterprise. The Linehams came to southern Alberta from Ontario and the

milled lumber, used to trim doors and windows, the balustrade that

protects the upper landing from the stair opening and the older hardware

have in their modest ornament a late Victorian flavour that perhaps

lingered longer in the colonial atmosphere of central Canada than in

the more sophisticated metropolis. Whatever the Austins' taste, and

Mrs. Austin's few surviving letters do not suggest an easy fit into the

stereotype of the pioneer woman, people building a house on Sheep Creek

in the early nineties would have little choice to exercise in terms of

the niceties of design unless a great deal of money was to be spent. By

the late twenties a broader choice was available, but in a household of

limited means was still restricted.

The same restrictions of variety and cost affected the interior

furnishings. Little can be said of the appearance of the rooms at

Cottonwoods before 1910 except that Mrs. Austin had both a piano and an

organ and it would be surprising if the rooms were not strewn with books

and magazines and sheet music. Apart from a taste for music, the Austins

were great readers; the attic when they left was filled with old numbers

of periodicals like Blackwood's and Etudes. Some of their

furniture remained in the house after they departed and an elm

double-drop-leaf kitchen table with turned legs and at least two chairs

with moulded backs and shaped seats, made of an extremely tough wood

also probably elm, painted black and exceedingly comfortable, are almost

certainly of Ontario workmanship. They are of a design still popular as

late as 1870. Whatever their virtue for today's admirer of Canadiana,

these pieces were not highly regarded as objects of beauty by my parents

and probably not particularly cherished by the previous owners who,

after all, left them behind.

The furnishings of the house after 1910 can be described in more

precise detail. The heavier pieces were generally of Canadian

manufacture and some were homemade, including a huge cupboard in the

kitchen, one of whose doors later became part of a built-in corner

cupboard which was among the many products of my mother's inventiveness

and my father's partner's addiction to joinery. Also in the kitchen was

something called "the bamboo cupboard," certainly not homemade though it

stood on a home made stand that concealed behind a discreet green

curtain my father's boots except for his best riding boots which,

because of the height of their wooden trees, were allowed a place in my

mother's wardrobe upstairs. "The bamboo cupboard" was perhaps not fully

appreciated as the elegant expression that it was of the first fruits of

the revolt against the overwrought elaboration of Victorian domestic

furnishings. Only its frame and those of the doors were decorated with

bamboo; its top, sides and doors were covered with carefully wrought

cane. It had a long career; for a time it served, on a more carefully

carpentered stand, as the sideboard in the dining room of the small

house in Okotoks which we occupied during the weekdays of the school

term, my parents having lost confidence in the one-room school nearly

three miles from Cottonwoods which my sisters had briefly attended.

Where "the bamboo cupboard" came from I do not know, but it may have

been from the same source as the chairs in the dining room which until

1928 was simply the eastern half of the sitting room. These chairs, a

set of six including two armchairs, had been purchased on a visit to

"the old country" at an auction sale of the effects of an invalid lady.

She must have furnished her house in North Wales under the influence of

William Morris for the chairs, of light oak with woven rush seats, had

the simple and slender lines of the movement he inspired. The dining

table, which could be extended to seat a crowded 12, was by contrast

dark and heavy, presumably made in eastern Canada. The finish was

probably described by the original vendor as "walnut." When not in use

it was covered by a fringed greenish-brown chenille cloth. The sideboard

was unashamed fumed oak, solid and simple in design and extremely

well-made. The date would be approximately 1910 as I believe it was

purchased new at a respectable Calgary furniture shop. It has — it

is still in the same room — a mirrored back and a plate rail which

displays some of the plates of a dessert service, certainly purchased at

a North Wales auction, I believe for half a crown for its 16 pieces, and

perhaps from the same invalid lady as her simple green and white Foley

(or Shelley) china was for a long time part of our daily life.

The dessert service, lavishly decorated in black, gold and deep

autumnal shades and with a curious crackled surface that suggests

earthenware rather than fine china, has never been identified as to

maker or period. Self-styled connoisseurs have both praised it as of

exceptional beauty and antiquity and dismissed it as the worst sort of

Art Nouveau, but no one has been able to interpret its obscure and

scarcely visible markings. Along with other odds and ends, the service

had been packed for export as "settlers effects" in a tin hipbath,

formerly the property of my Flintshire great-grandmother. So skilfully

was it packed that it survived the passage, all except the two-tiered

centre comport which broke at the join between the two parts. My mother

placed it in the rubbish bin where it was shortly observed by her

Scottish neighbour, a lady noted for her business acumen and her plain-speaking,

who did not hesitate to reprove this reckless discard of a

valuable object that could be easily and inconspicuously mended.

Perhaps tired by her exertions in putting her house in order and

possibly resenting this Scottish aspersion on her own West-Country

industry, thrift and appreciation of fine things, my mother rather

crisply offered the comport to its admirer. The gift was carried off;

what became of it was never revealed though I was a frequent and, I

think, observant visitor at the recipient's house. The episode, trivial

though it may be, indicates how casually household objects were often

treated even though their merits were appreciated. My mother was on

another occasion scolded by a male caller for using an oriental rug as a

hearth-mat. It had been a family relic, but had been tied across

great-grandmother's hipbath and the projecting handles had rubbed holes

in it. My mother mended it carefully, but stuck to her guns and the rug

ended its career at the back door.

The sitting room chairs included a gold-oak armchair with wide wooden

arms and an adjustable back, dedicated to the comfort of my father's

partner. Its two loose cushions were upholstered in a hideous but

durable velour, a kind of plaid in reddish-brown and black that recalled

Queen Victoria's worst excesses at Balmoral and Osborne. Such chairs are

commonly illustrated in Canadian newspaper advertisements and catalogues

from the 1890s to the 1920s; they are sometimes characterized as

"mission." A sturdy table stood beside this chair to support a lamp that

must have been the most commanding object in the room. The operative

part of the lamp was of glass, but this was set in a bowl supported on

an elaborately decorated column on claw feet, all silver-plated. This

formidable base was surmounted by an equally elaborate silk shade. Where

it came from I do not know; perhaps it was a wedding present, perhaps a

trophy of the auction room. When it was new it must have been most

expensive and I am quite sure my parents would not have thought of such

an extravagance. It may have been Edwardian, but I am inclined to think

of it as high Victorian at its most robust. As a lamp it was an early

casualty of childrens' play — the table on which it stood had, like

the dining table, a cover that reached almost to the floor and served

once too often as a safe refuge in a game of hide-and-seek — but as

a stand for many years it held a plant — wandering Jew or Irish

moss — until at last the silver-plate yielded to the many cleanings

dictated by the sulphur-laden air that was carried eastward from the oil

field across the creek at Turner Valley.

The other furnishings were less substantial. My father occupied a

wicker armchair that had the same light and elegant lines as the invalid

lady's dining chairs; my mother, a tub-shaped chair with legs and back

trimmed with cane or rattan and upholstered in green. The latter chair

had, at first only on occasions when guests were invited, a slipcover

made of a heavy cretonne or chintz closely patterned in blue and white

which matched the slipcover my mother tailored to fit the Winnipeg

couch, called "the sofa," whose rather drab green-covered mattress with

its pendant frill did not greatly please her eye. There were a number of

cushions on "the sofa," whose covers changed with the years. One, very

much her "best," was a floral chintz, predominantly rose, with a corded

edge. I can remember removing it from under the feet of a visitor in

1920; I noticed it not long ago still doing duty as part of the bed of a

much-cherished cat. An upright piano and stool were not part of the

original furniture but were added about 1918. The only other piece of

furniture I recall was a small fumed oak desk with two bookshelves

below; the lid dropped forward to form a writing-surface and though it

was really intended as a lady's desk, it was in its pigeonholes that my

father kept his papers and there he wrote his letters, including his

weekly letter to his mother. The desk, very simple in its lines and

extremely well-made, was probably purchased in North Wales in 1910 as

it was a gift from my father's sister and seems to me to reflect her

advanced and somewhat austere taste (Figs. 8, 10).

8 The west end of the sitting room at Cottonwoods, circa 1912. At

the upper extreme left may be seen part of the shade of the lamp to

which reference is made in the text.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

9 The sitting room, Christmas, circa 1913, showing may father's

wicker chair.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

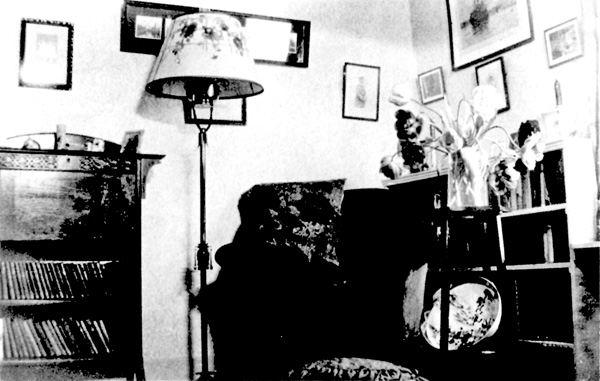

10 The southeast corner of the sitting room added to the Cottonwoods

circa 1929.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

The carpet was an Axminster of bold design, richly floral and

predominantly red. It covered most of the sitting room side; the floor

of the dining room part had a brown linoleum intended to imitate parquet

and requiring at least as frequent waxing and polishing. The illusion

of wood was scarcely sustained by the brass tape

that covered the joins. The kitchen linoleum, a green "inlaid," was

prone to lose bits of its inlay not by any inherent defect or for any

lack of care, but because of the roughness of the wooden floor

beneath.

The curtains of the four windows did not match. In the sitting room

the two windows had delicate lace curtains, net with a pattern

appliquéed over it in a heavier thread. They were floor length and tied

back to allow the view to be seen. There were no side drapes, though a

heavy red one was pulled over the outside door to minimize draughts.

Instead, cream-coloured blinds on rollers with a spring action gave

protection against the sun and were pulled down in the evening more for

cosiness than for privacy which was adequately assured by the mile of

uncertain trail that led to the nearest public road. For the two dining

room windows my mother made simple straight curtains, of cream-coloured

casement cloth, whose brass rings pulled back and forth on thin brass

rods. At a later date the faithful carpenter made window boxes that held

houseplants and which, on the coldest nights, could be conveniently

removed to a place of safety.

This room, like all other rooms in the house, was calcimined

annually. Pink and green were the common colours, but my mother was quick

to take advantage of other shades when these became available. She was

also soon experimenting with wallpaper and became adept at hanging it

with the assistance of anyone tall enough to be useful. The doors, the

wooden trim around them and the windows, and the skirting-boards were

varnished though it was not far into the twenties when the possibilities

of light-coloured paint were discovered and one by one the rooms

transformed.

There were many ornaments, though fewer than was perhaps the general

fashion. Two of my English uncles had a taste for carving and fretwork

and contributed a clock-case, a rather unstable plant table, whose lower

shelf displayed a Japanese bowl in the Imari style, and a small hanging

corner cupboard which had a lock and key and served as a medicine chest.

All three were painstakingly carved and stained black. A large oak tray,

left in its natural colour, was carved in a representation of the arms

of the City of Gloucester. Bits of china which varied from a Chelsea

piece, badly chipped but of some rarity, to souvenir plates of the

coronation of George V, small silver boxes and mugs, a small brass

dinner gong on a stand, vases of flowers when flowers were available and

framed photographs all found a place somewhere. The pictures on the

walls were a heterogeneous lot reflecting, among other things, my

father's interest in horses and my mother's hobbies of painting in oils

and watercolours and of photography. The only picture of more than

sentimental value was a sketch in oils of an old man's head and

shoulders by George Morland, one of the many he is said to have done to

pay for a drink. It had caught my father's eye at an auction and he had

bought it for the proverbial half-crown. The large photograph of race

horses belonging to King Edward VII, showing the owner as well as the

trainer and jockey, did duty for the portraits of royalty so widely

popular throughout the empire. Several colour prints of the works of the

cowboy artist, C.M. Russell, recalled my father's early experience in

South Dakota and Montana.

The room was heated by a stove, the only source of heat, except for

the kitchen range, for the whole house. Its stovepipe disappeared

through the ceiling and reappeared in my parents' bedroom, whence it

crossed the upstairs landing to the single chimney which also served the

kitchen stove. Perhaps the earlier occupants, ageing central Canadians

that they were, had a stove upstairs. There was space for one on the

landing and an opening for another stovepipe, but there was never a

stove there after 1910. Instead the space was enclosed to accommodate a

chemical toilet which could be served by the convenient vent.

The first sitting room stove that I recall was a gigantic "base-burner"

which could, with suitable attention, be kept going for 24

hours. Its place was taken, when the chimney and stovepipes were cleaned

in the spring, by a small air-tight stove. Then the briquets which fed

the voracious appetite of the base-burner ceased to be available or

perhaps became too expensive and it was relegated to the granary and

replaced by a Quebec heater, splendidly black and much ornamented by

gleaming steel, an excellent and economical source of heat but incapable

of maintaining a fire through the winter night. Cutting wood for the two

stoves was a time-consuming task especially as it was all done by hand

using axe and saw. Willow was plentiful on Sheep Creek and its quick and

intense heat made it the wood preferred for cooking.

The four bedrooms allowed even more scope for improvisation than the

downstairs rooms. The beds had enamelled iron frames, some with

ornamental brass rods, and were severely practical. There was one

feather mattress but it was regarded with some suspicion as possibly

unhealthy and its contents were gradually transferred to make pillows,

cushions and the quilted "eider-downs" that supplemented a supply of

blankets that never-seemed quite adequate. Each bedroom had its

washstand, all but one made of packing cases of one size or another,

suitably padded, lined and draped. Dressing tables and bedside tables

were similarly contrived. Only two rooms had a chest of drawers; these

were of eastern Canadian manufacture as was my mother's dressing table.

The narrow boards of the walls in two bedrooms were later painted or

papered over, but for a time those in the

room my sisters shared were covered with pictures cut from every

available source and pasted to the boards.

I cannot begin to describe in equal detail the other Sheep Creek

houses that I knew well in the years between the wars and can offer

little more than impressions. Out of the composite of those impressions

emerges a sense that they had more than a little in common, yet they

were of great variety and individuality and all reflected the

backgrounds and characters of their owners. It is sad that so few have

survived, as Cottonwoods has survived, as crystallizations of nearly a

century of foothills living.

Many of them were of log, of great variety in size and design, and

almost without exception built in successive stages. One of particular

interest, the Gate Ranch house (Fig. 11), lay far to the west with a

long view up the meadows of the north fork through the foothills' ridges

to the splendour of the Rockies. Like many of the earliest houses, it

seemed to have been sited with regard to the outlook and its dependent

buildings and corrals were, as was generally the case, so placed that

they did not obstruct the prospect from the main rooms of the house.

From the first the house was seen not merely as an adjunct to the work

of the ranch, but as the foundation of the owner's private life and the

setting for his social life.

11 Detail from a painting of the Gate Ranch house. The original log

structure was built in 1885, the additions were made later.

(Painting by Robert Basilici; Elizabeth Rummel Collection, photo by A. Harmon.)

|

The first dwelling here proved to be too close to the creek and this

may explain why the first unit of the house that developed was more

carefully constructed than many of its contemporaries. The builder and

owner, Joseph T. Waite, had a knowledge of carpentry acquired in

northern England and in the oldest part of the house the logs were

squared and the corners painstakingly dove-tailed. This part of the

house, the bar to the future T, was almost square, divided into two

rooms, one much wider than the other, and with a steep stairs between to

an attic which was high enough to provide sleeping quarters. The second

stage, the stem of the T, was much more ambitious and reflected the

tastes of a new owner, a former British officer. It consisted of two

very large rooms, a sitting room and a kitchen-dining room. These rooms

were both lined with narrow tongue-and-groove which darkened with age.

The two two-paned sashes of the windows were set to move horizontally

rather than vertically; these were called "lazy windows" and their

effect was to heighten the impact of the view and to emphasize the

horizontal lines of the house as a whole. The logs of this and other

parts of the house and of the outbuildings were left in the round with

the saddle-back corners characteristic of much foothills log building

(Fig. 12). At right angles to the kitchen was the bunkhouse, itself a

building of considerable size. The roof of the bunkhouse projected to

join that of the kitchen and thus gave a sheltered passage which had a

door at its north end and at once gave communication between and separated the

bunkhouse and the kitchen. The passage at its south end was open to the

verandah that stretched along the east wall of the sitting room and, in

the years between the wars, looked over a flower garden which was thus

well-protected on the north and west from wind and frost. Another range

of buildings was destroyed by a fire from which the house narrowly

escaped and the working buildings and the corrals were, when I knew the

place best, all to the northeast of the house. They were admirably

maintained and kept meticulously tidy. Some of the outbuildings, all of

log, were stained or allowed to weather to a silvery grey, but the

roofs, like that of the house, were painted red. The logs of the house

were regularly whitewashed and the trim painted black. The house was

banked with earth; it had been banked so often that by 1930 the grass

grew almost at the level of the windows and the whole house appeared to

grow out of its surroundings. It no longer exists but I am sure that the

scene of which it was the focus was for many others, as it was for me,

the epitome of the log house of the southern Alberta foothills.

12 This log house was built circa 1932 at Kew, Alberta, its owner had

grown up at and greatly loved the Gate Ranch and the houses in many

ways resembled one another.

(L. G. Thomas Collection.)

|

Like the other houses of Sheep Creek, the furnishings of this house

were a miscellany gathered over the years, some passed down from earlier

occupants, many improvised, and some made by a handy craftsman who could

easily manage a shelf, a bench or a cupboard even though he certainly

would not have considered himself a cabinetmaker. One of the things

that distinguished this house in the years between the wars was the bold

use of colour, in paint and in materials, in a way that recalled the

vernacular decorative arts of south Germany. The family then occupying

it were indeed from Munich though with connections reaching into almost

every European country. The house was full of books; though well-filled

bookshelves were no rarity in the Sheep Creek houses, one did not often

find a library in four languages, German, French and Italian as well as

English. Nowhere was the synthesis of the exotic and the local more

gracefully and unselfconsciously accomplished. It never for a moment

seemed odd that at one end of the sitting room there should hang a

portrait painted by one of Europe's most fashionable artists while in

the corral nearby the subject demonstrated her notable ability to shoe a

horse.

Though sandstone was locally available and much used in southern

Alberta prior to 1914, Sheep Creek had only one house, the Viewfield

Ranch house (Fig. 13), wholly of this material, though another nearby,

now derelict, had a basement and ground floor of stone and a charming

adjoining garden walled on two sides with blocks from the same quarry.

The Viewfield Ranch house, which like many others commanded a handsome

prospect of the valley and the mountains, was built by a well-off Englishman.

It was of a very simple design; a long, low rectangle with a wooden

verandah placed asymmetrically to shelter the front door. The huge

attic, lit by a dormer window, was not used. The plan was very English.

The front door opened into a square sitting room, almost a hall in the

English sense (Figs. 14, 15). It had a brick open fireplace in one

corner; the chimney served the stove in the adjoining dining room, a

somewhat larger room to the left, and the range in the kitchen behind

the dining room. What seemed a long passage led off to the bedrooms to

the right of the sitting room. The upper sashes of the windows had a

number of small panes; the thickness of the stone walls gave the windows

very deep ledges. The house must have been expensive to build; apart

from the skilled craftsmanship needed to work with the local stone, the

plasterwork of the walls and ceilings and the tiled bathroom were

exceptional in this period and this setting. The date when the house was

built is not known; the other house where stone was used was built about

1906, perhaps a little earlier. Both had furnaces, though these were not

notably efficient, and one had "waterworks" and, by about 1920, a

somewhat tempermental electric lighting system.

13 The Viewfield Ranch house, probably taken soon after it was

built.

(S. Sinclair-Smith Collection.)

|

14 The sitting room fireplace at Viewfield Ranch, probably taken

in the 1920s.

(S. Sinclair-Smith Collection.)

|

15 Another view of the sitting room at Viewfield Ranch, probably

taken in the 1920s.

(S. Sinclair-Smith Collection.)

|

Everyone had a kitchen garden and almost everyone a flower garden

though the latter were not always as faithfully maintained or as

ambitious as that at Cottonwoods. Again the gardens reflected the

transatlantic heritage of most of the gardeners. They were not

elaborate; few attempted more than the cottage garden of England. Plants

and seeds were exchanged and the hardiest flourished. Scarlet lychnis or

Maltese Cross, perhaps one of the first "exotics" attempted on Sheep

Creek, flourished everywhere, notably at the Millarville church. The

humble hop and the annual cucumber vine were popular creepers; Virgina

creeper was not considered hardy enough to withstand the late and early

frost of the foothills. Though the cottonwoods attained a respectable

height along the creek, other than native trees grew slowly though

gardeners were soon planting Russian poplar, Manitoba maple and caragana

to give shelter not only from the wind but also from unseasonable

frosts. The gardens and indeed the whole landscape of Sheep Creek by

1930 gave a feeling of sheltered lushness very unlike the stereotype of

the prairie, but photographs dating from the eighties and nineties

suggest a much more open and less wooded view and indeed these were the

years when prairie fires were still a menace. The present garden at

Cottonwoods dates only from 1910 and it was much enlarged to accommodate

the sheltering trees at the end of the twenties. Dating the gardens is

even more difficult than dating the houses and their furnishings, but I

am inclined to think that Cottonwoods was exceptional in the absence of

a garden in its early years. I am inclined to think that by 1890, and

more certainly by 1895, almost all the early settlers had attempted

something like an ornamental garden, however modest.

An extraordinary number of Sheep Creek houses had tennis courts; I

can think of at least 16. They were grass courts though it is possible

that the tennis club courts, near Ardmore, were clay courts, as the

second Mrs. Welsh was a player of near championship quality. The vogue

for lawn tennis seems to have spread to Sheep Creek almost as soon as

the game was invented in North Wales and its popularity survived the war

of 1914-18 though by the end of the thirties few of the courts were

still maintained. "Maintained" is a relative word for the courts

reflected the same talent for improvisation as the furnishing of the

houses. The one at Cottonwoods was largely my mother's work. There was a

piece of more or less level turf directly south of the garden and

approximately the size laid down by Pears' Encyclopaedia, a

much-thumbed work of reference. The lines, determined by the same

authority, were laid out with lime and an old broom. The net had to be

taken down between times as stock roamed at large; indeed to make the

court my mother cut turf to fill a cow path that bisected diagonally her

chosen site. The court ran east and west, which gave a certain advantage

to the players with the sun at their backs. There were no backstops and

balls had frequently to be retrieved from the little creek that in wet

seasons ran only a few feet beyond the court's southerly limit. Our

equipment was modest; balls were used year after year, surviving

frequent total immersion, and one of the racquets was of such antiquity

that, judging from its curiously unbalanced shape, it must have been

made before any nonsense about standardization.

The Sheep Creek houses that I remember had great individuality yet

they reflected certain common concerns that grew out of a diversity of

backgrounds. Their mood was to a degree nostalgic, a harking back to a

past that was remembered with affection, if not always, or even often,

with regret. Their mistresses showed remarkable adaptability and in the

interest of comfort and convenience they did not hesitate to

compromise. Thus they drew their furnishings from a variety of sources.

In one house a fine pair of early Wedgewood vases might sit on a

carpenter-made cupboard or a Chippendale dressing-mirror on a golden-oak

chest of drawers from Lindsay, Ontario. Family portraits from the 18th

century might hang side by side with a carefully tanned coyote-skin. No

one furnished a house with antiques, but if they had cherished

possessions from another age and another way of life they used

them and enjoyed them. On these extraordinary juxtapositions the

patina of a generation's living imposed a congruity of their own.

|

|

|

|