The Prince of Playgrounds

GADDINGS AROUND GLACIER.

At our Hotel right here in the heart of the Selkirks we have every comfort afforded by the world's hostleries in the heart of things near the busy haunts of men. Moreover, a hard-to-describe feeling of rest and relaxation and letting down of tension came to us the moment we stepped within the portals of this ice-guarded haven of rest. We forget that there is a world of noise and clamor and competition beyond these hills, and gladly we cast our dolours down. With a soul-satisfied feeling of luxuriousness, we tuck our suitcases into a corner and say to each other, "Let the world and the train go by. Here for some days we rest." The wise man gives himself up to the spirit of the place, and he who is learned is bidden to forget it, and to become simply acceptive as a little child.

"See thou bring not to field or stone

The fancies found in books;

Leave authors' eyes, and fetch your own,

To brave the landscape's looks."

Each day we put knapsack on back, and fare forth along a new trail.

MONDAY. This morning we make an early start for The Caves of Cheops, a walk of seven miles by a good bridle-trail. If office work has made seven miles seem a long distance to tramp, staunch little pack-ponies are at your bidding. The Caves are above the snow-line and at the head of a smiling valley. The chief chamber lifts its roof two hundred feet from the floor-line, its sides scintillating with crystals of quartz. Cheops was brought to the ken of modern man by one Charles Deutschman, who tells us that the quaint caverns have been eaten out of solid rock by the water-action of centuries. The ceilings are polished layers of overlapping rock, the walls in places lifting themselves up the veritable chiselled rafters of some cathedral-dome. Great basins of water point to waterfalls of a past age, and we would fain let our fancy make of them the drinking-bowls of some Titan ancestors. The luncheons put up for us by the good people of Glacier House are put down by ourselves with gusto and without delay, and as we rattle over the stony path homeward little reck we whether stocks are up or down on the New York Exchange. We sleep the sleep of little children and are acquiescent in any plan made for the morrow.

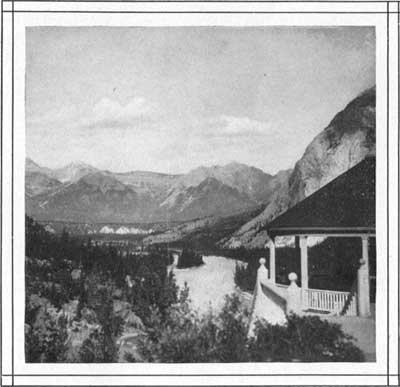

Bow Valley.

Bow Valley.

|

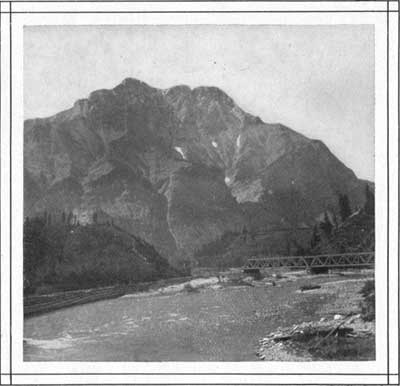

Cascade Mountain from Anthracite.

Cascade Mountain from Anthracite.

|

TUESDAY. To-day we take The Cascade Trail. We corkscrew our way up the mountain opposite the Hotel, and wind through some of the grandest fir growth in the whole of the Selkirks. Bending back on our trail, the Valley and the Hotel burst upon our view, and the lush green meads above. We get a splendid view of the long slanting escarpment of the Big Glacier, and a short drop down the slope lands one at the wee pavilion we saw from the Valley below. We need no guide for this climb, it is perfectly safe, and if we start at eight in the morning, we can complete our undertaking by noon. But it is not likely that we will be so satisfied. Everywhere around us the wild flowers are a great joy, and the party soon breaks into little groups hailing with the gladness of released children, the discovery of new friends in the flower world springing side by side in the same cleft with the old posies and nosegays that sweetened our childhood meadows. One seizes upon an Alpine Anemone, that rare white buttercup shaded off to pale blue, "And where a tear has dropt a wind-flower blows." Another brings as treasure-trove the big bright leaves of the hellebore, the largest and most splendid green-tinct flower which blows in the mountain. Stretched on the moss the finder quotes from Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy,

"Borage and Hellebore fill two scenes,

Sovereign plants to purge the veins

Of melancholy, and cheer the heart

Of those "black fumes which make it smart."

No need to sing, "Away, loathed Melancholy," on the Cascade Trail, "Away with hunger" is much more to the point, and a general scramble is made for the Hotel.

WEDNESDAY. The Asulkan Valley. It is horses this morning. A very decent pony-trail lands us about six miles up the Valley at a sputtering torrent. An hour's good climb and the culmination of the Pass gives a gorgeous panorama, Fish Creek Vale far below with five miles of glittering glacier to the right. It is truly Alp piled on Alp, a world of white to which we have won through forests of fir.

THURSDAY. Mt. Abbott. We start early to-day for a whole day's ascent. First we reach Marion Lake, a mountain mere tucked away in a cleft on the hillside. A good blazed trail takes us to the mountain summit and a breath-catching view of forty live glaciers. Winding seventy yards above Marion and trending in toward the foot of the Rampart is a trail which wins the hearty encomium of all who tread it. This day, too, is rich in flowers. We turn a sharp corner to greet an old friend somehow seeming strangely out of place in this moist swain so high above its usual habitat. But there is no doubt about the identity of this childhood friend,

"The graceful columbine, all blushing red,

Bends to the earth her crown

Of honey-laden bells."

Much more in its proper setting appears the Moss Campion, which in the Canadian Rockies has been discovered full 3,000 yards above sea level. Here, the last vedette of the flower-legion, close-clinging to the earth,

"Cleaving to the ground, it lies

With multitude of purple eyes

Spangling a cushion green like moss."

FRIDAY. Disdaining superstition, we choose Mt. Sir Donald for this day. High above his fellows, 10,600 feet uplifted beyond sea-level, his peak has been a silent challenge to us all week. It takes about sixteen hours to make the ascent, and every one is warned against being foolhardy enough to attempt the climb without guides. Even with these experienced Swiss climbers to show the easy way across crevasse and glacier, the climb is difficult enough to satisfy the most ambitious. But every one who takes it is richly repaid, and comes to a downy bed with a feeling of blended exaltation and sane weariness, "Something attempted, something done, has earned a night's repose."

But the Yoho and Banff call us on, and with a sigh of half-regretfulness we pay our score to the landlord and step once more into our luxurious Limited with faces turned eastward.

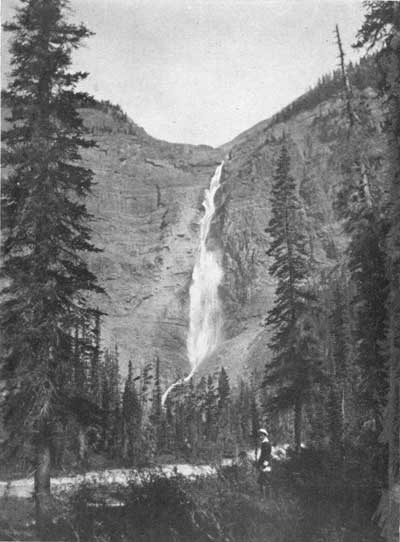

Takakkaw Falls, Yoho Valley. 1347 ft. high.

Takakkaw Falls, Yoho Valley. 1347 ft. high.

|

YO! HO! FOR THE YOHO!

There are really three courts in this Rocky Mountain Prince of Playgrounds. First, Glacier where the Selkirks impinge on the Rockies as we approach from the Pacific; second, Yoho, reached from Field at the very summit of the Rockies; and, lastly, Banff, where we drop from the Rocky Range to the foothills that creep away to the wheat-plains of Golden Alberta. It was the late Jean Habel, a veteran climber of Berlin who opened up to the world the wonders of the Yoho Valley. To reach the Yoho we leave the train at Field, and here, too, Emerald Lake is in pleasing proximity. At Field we are but ten miles beyond the Great Divide whence streams pour their diverging tribute eastward to Hudson Bay, westward to the Pacific. The first spectacle to challenge our vision as we alight at Field is massive Mt. Stephen lifting itself up 10,500 feet above the level of the ocean, and here, as at Glacier, a splendid C. P. R. Hotel, Mt. Stephen House, invites to leiusre and pleasure. At Field we open the doorway of a valley more majestic than any yet explored by man, the Yoho far surpassing the Yosemite. As the years go on, this valley must prove a lodestone most magnetic to those who wander the earth seeking pleasure. Guarded by giant peaks, stupendous glaciers, and a wonder-waterfall, the Yoho Valley was a rare revelation to the hunters of mountain-sheep who first stumbled upon its hidden beauties. The Indian name for the waterfall of the Yoho, "Takakkaw!" (It is beautifull), still clings. The fall is over 1,000 feet in height, and is shot from the shoulder of a glacier direct into the Valley of the Yoho.

Swiss guides at Mt. Stephen House make assured the safety of all ascents. The wise tourist will spend a week at Field, and if he is an outdoor man and can afford the time, another week under canvas in the Yoho. Remembering the delights of Glacier, the challenge of new scenes is strong upon us as is also the lure of that mystical vale beyond. We are all strangely quiet this still white night standing at the door of this cosy caravansery of the hills and watching the last shaft of the sun shimmer into neutral tint.

"And the landscape, chill and wan,

Softer aspect taketh on;

Something mystical, magical,

Hovers, glamors over all;

Then a film drapes the skies,

And the night hath softer eyes;

Something in the heaven aglow,

Something in the earth below,

Toward glad dreaming turns the brain,

And the heart grows young again."

A WEEK OF WIZARDRY.

With Mt. Stephen House as a base, we are going to add another week's treasures to memory's casket.

MONDAY we will explore the fossil-beds. These occur in the lower reaches of the route leading to the peak of Mt. Stephen, about two miles from Field. The trail over glacial moraines is good, and leads us to not the least interesting point in the whole range of the Rockies. A wide-extended deposit of trilobite fossils is here exposed nearly at timber-line on the flank of the mountain; millions of specimens are ours for the taking. We can't help crushing hundreds of them as we walk, and, sitting down we gather them as one gathers blueberries in a blueberry swamp. Pushing its soft way through these fossils that are older than history is "the little speedwell's darling blue." What Alpine climber does not love the small azure-blue blooms, the last blossoms growing where kindly soil gives place to glacier ice and crevasses of the moraine!

Twin Falls, Yoho. 750 ft. high.

Twin Falls, Yoho. 750 ft. high.

|

TUESDAY. To-day we essay the Natural Bridge, an easy walk of three miles, with the objective point of our tramp set in an exquisite framework with Mt. Stephen a superb background. The Natural Bridge surmounts a narrow archway worn by the water-attrition of ages through a massive rock-wall. Through the narrow orifice the great volume of the Kicking Horse forces its way with a noise that drowns our voices. A quarter of a mile farther on the troubled river drops into a narrow canyon and carries its tortured course by thundering cascades under sheer cliffs, giving a succession of moving pictures tempting to every slave of the camera. And above us and around us are the mountains. Every country of the Old World cherished a sacred peak; for the Japanese there was Fusiyama, the Cingalese had their Samanala, Greece its Olympus, and Armenia its Ararat. In a world of change the mountains are immutable. Mt. Stephen might well stand the titular peak of the Canadian. One needs but introduce the prefix "Saint," and the trick is done. Saint Stephen has not proved himself a monetary mountain, he is not inhabited, nor paintable, and scarcely describable, but to look upon his face is a clear joy, and we are so replete with soul-satisfied rest, that willingly would we build at his base one, two, or twenty tabernacles of praise.

WEDNESDAY and THURSDAY we spend at Emerald Lake, a rest-resort six or eight miles from Field, reached by a splendid road along the bank of the Kicking Horse and then skirting the foot of Mt. Burgess. A superb chalet awaits us at the Lake; it is the joys of the Alps joined to the urban comforts of a Waldorf-Astoria.

The coloring of the Lake is rich and wondrously vivid, and the Chalet gives us a splendid vantage-point from which to study it. Emerald Lake is enclosed by pointed pinnacles and uplifted slopes, the clear-cut face of President Mountain in front, with the sheer precipices of Mt. Burgess and Wapta's rough ramparts. Lake Emerald borrows only to repay, in her pellucid face she gives back every pencilling of towering cliff and tree-girt shore.

The snow-tipped peak of Mt. Vaux, one of the Otter-tail group, is a conspicuously magnificent and to-be-remembered object as seen from Emerald Lake on a soft evening of summer. The gold-red of the setting sun, the roseate tints on the mountain top, the clear lake water framed by sombre firs and dank rocks, is a set-piece that memory cherishes, and which comes back across the years, a joyous retrospect.

FRIDAY we push on to the famed Yoho Valley; a splendid trail carries us from Emerald Lake up and ever up to Lake Yoho. Passing round the lower end of Yoho Lake, we cross the rivulet that debouches from it, and continue our pathway through the pines.

Soon there bursts upon our hearing the reverberating thunder of some giant waterfall, and thirty minutes' tramping brings us out sharply from the trees to a magnificent view of Takakkaw Falls, a mile away as the crow flies, on the far side of the Valley. The glorious torrent, spurting out from its icy cave, tumbles like tempests down a twisted chasm till, making the verge of a sheer cliff, it leaps out from the rocky escarpment 150 feet, to descend in broken jets and spill itself a thousand feet below.

SATURDAY has come, and we climb no more. To-day we sit upon the grass and look up into the trees. Both have music to offer us if we will but tune our ears to hear.

"In the summer of the summer,

When the hazy air is sweet

With the breath of crimson clover,

And the day's a-shine with heat,

When the sky is blue and burning,

And the clouds a downy mass,

When the breeze is idly dawdling,

There is music in the grass.

Five species of trees make up the forest family in the Summit Range. The Douglas fir clusters in the foothills and the mountain valleys; it is the largest conifer and in favorable corners points its mast-top two hundred feet into the air. The black pine also cannot endure high altitudes, while the spruce presents itself everywhere from the lowest clefts of the low hills to the utmost limit of tree-growth. The four hundred concentric rings of some of these old spruce stumps would point back to a baby seed-sprouting in some moist springtime when this old world of ours was six hundred years younger, and York and Lancaster fought under their rival banners of red and white.

The balsam-fir is the friend of the camper, it makes his bed and his watch-fire. He who smells "wood-smoke at twilight" sniffs the smoke of balsam-fir. But most beautiful of the conifers is Lyall's larch, the southern limits of whose growth have not yet been determined, but lie probably in Montana. The heavy branches, green-tufted needles and irregular gray bark of Lyall's larch combine to make of it a beautiful whole. Clinging to the northern limit of the tree-line, it bears every evidence of being a good fighter. Its ancestral enemies are the blizzard and the snowstorm which have it at a disadvantage in its clinging habitat on the high ridges and exposed uplands. Scars, gnarled trunks and snapped branches give a dignity to every Rocky Mountain member of this family. Lyall's larch has no more need than the devout Highlander had to pray for "the saving grace of continuance."