The Prince of Playgrounds

VICTORIA THE BEAUTIFUL.

"Serene, indifferent to Fate,

She sitteth at the western gate—

The warder of the continent."

This is the city which Edgar Wallace, the famous correspondent of the London Daily Mail, characterizes as "The Little-Johnny-Head-in-the-Air City of Canada." The atmosphere of Victoria is unique. The idle tourist, spending a summer week within her borders, carries the witchery of her charm with him where'er he wanders. What makes that charm? It is compounded of many simples—the sea has much to do with it, the multitudinous roses contribute, the gentle voices of the people play no small part, the breezes, soft with suggestiveness from the cane-groves of Honolulu and the gardens of Nippon.

The sun never sets with greater beauty than over the edge of the Sooke Hills, tipping the rough-hewn silver of the Olympics with a rosy glow and spilling itself in prodigality over the waters of the Fucan Straits. On the streets of this polyglot town the Indian clam-digger brushes the immaculate red tunic of Tommy Atkins, and the sailor from Esquimalt hobnobs with the Hindoo. The City of Victoria runs out in broom and buttercups to the country lanes, and the firs of the forest creep into the city streets.

One feature of Victoria commends itself to visitors: an active Tourists' Association, with centrally located headquarters and a permanent secretary. You should first make your way to these rooms, and register. The officials will take you in hand, find you a boarding-place, and plan so that you will get the maximum of enjoyment with the minimum of money and time. The one-day visitor should see the Park and Museum, take the tram to the Gorge and historic Esquimalt, and in the Tourist Tally-ho enjoy the delights of the world's grandest ocean-drive.

It is monstrous pity, though, to leave Victoria under a week's sojourn. Goldstream should he visited; go to Oak Bay and look across the water to historic San Juan Island which the wisdom of the German Emperor plucked from Britain's crown to sparkle in the neckerchief of Uncle Sam.

Get up early one morning and try the salmon-trawling; it will not be exceptional luck if you bring home half a dozen 10-pounders before breakfast. As evening lights close in, a walk through the Golf Links where the pheasants are calling in the long grass, and the meadow-lark announces to all and sundry that "God's in His Heaven, all's right with the world," will send you to bed sane and content.

VANCOUVER.

Then off to Vancouver, the Pacific terminal of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Princess Victoria carries you again, and it is another four hours' run. Start in the early morning, by all means. You pass through a wonder-archipelago without a duplicate in the world's scenic routes. What a riot of color as you pull out from Victoria Harbor and creep coastwise round Beacon Hill and the beaches of Shoal Bay! With a toot of recognition from the smokestack, you glide past Cadboro Bay, where the mile-long crescent of silver sand echoes back the holiday noises of half a hundred camps.

Out on the sunken ridges of that burnt-umber reef a pod of hair-seals whimpers in the morning sunshine, and far across are the lime-cliffs of Salt Spring. That dark ribbon of smoke marks the mid-channel passage of a tramp-steamer from No-Man's Land, and in the offing are the bellying sails of South American lumber-ships, and in front and behind and on either side lie the islands of the Gulf of Georgia. The Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence are small and puny in the light of these pine-crested and sea-washed submerged tips of buried mountains. See the Indian canoes stealing silent up the mid-island channels, and hark! the cry of the loon comes from some unknown quarter, and a band of heavy-bodied ducks trail their wings across the polished surface of the sea in clumsy flight at our approach.

And then the City of Vancouver. The City of the Couching Lions dips its feet into Burrard Inlet, and stretches its encircling arms across to the yellow sands of English Bay. At the sea-front here the world-end steamers wait; at the long docks we see them, craft from San Francisco, China, Japan, Australia, Honolulu, and far Fiji, and as the seagulls whistle in the rigging and the long combers sweep in from around Brockton Point, we half wish that we might listen to the siren voices that call us seaward. Truly, here "East is West, and West is East."

THE VALLEY OF THE FRASER.

But Eastward we go toward the snowy silences and cool alluring rest of the Rockies, into the far fastnesses in the heart of the ancient wood. Trout-fishing in endless variety, with deer-hunting and bear-shooting and an occasional mountain-goat in the hills along Burrard Inlet may well tempt the sportsman for a rare week. Every one interested in economics must take the electric tram across to New Westminster on the Fraser, and there inspect the salmon industry, full of compelling interest.

At Westminster Junction, turn your back to the sea, have your travelling bag and impedimenta tucked away in one of the parlor-cars of the Imperial Limited and lean back luxuriously in anticipation of the most pleasureable railroad trip you have ever enjoyed. The service on this line is unexcelled in the world to-day, the table is something you will remember with a backward thought of pleased contentment, and Nature opens up to you a panorama of magnificence which deepens in its generous lavishness as you travel eastward and upward from the sea's level.

At Hammond, by the side of the mighty Fraser, you catch a view of Mt. Baker which you will long remember. Looking at it through the immense trees of Douglas fir you are reminded of some of the striking prints of Fusiyama. It is a very riot of color. Down at your feet the drying salmon of an Indian camp forms a vermilion dab on the landscape, the Fraser pours its clear-hued tribute ocean-ward, over all is the bluest of blue skies, and the piny air is a tonic.

With a last glance at the isolated cone of Mt. Baker, now rosy pink in the distance, losing itself in the clouds full 14,000 feet above the railway level, we pass Nicomen, and reach Agassiz, the station for the hot sulphur springs of Harrison Lake, five miles to the north. All way-weary travellers should spare a week-end off at Harrison Lake. Were its beauties known, this place would be besieged by pleasure-parties during half the year. As it is, the weary globe-trotter who by half-accident finds it out, with malice aforethought obeys the Scripture phrase, and "goes and tells no man." Harrison Lake has the largest salmon-hatchery in the world, to tempt the interest of the scientific; it has a St. Alice Hotel, whose management know how to minister to tired mortals, and it has above and beyond this when the evening lights lose themselves on the lake-edges, and the shadows fall slantingly across Mt. Cheam, a witchery which once felt haunts one to the last word of life's last chapter.

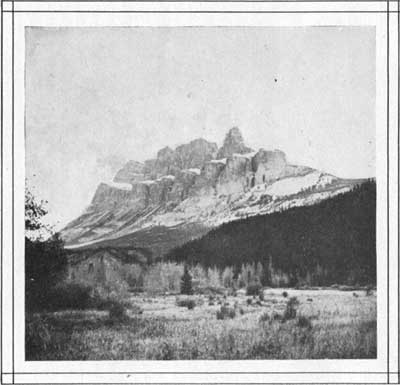

Castle Mountain, near Banff.

Castle Mountain, near Banff.

|

Government Bath House, Banff.

Government Bath House, Banff.

|

ON AND UP.

"O foolish ones, put by your care.

Where wants are many, joys are few;

And at the wilding springs of peace.

God keeps an open house for you.

But there be others, happier few,

The vagabondish sons of God

Who know the by-ways and the flowers,

And care not how the world may plod.

They loiter down the traffic lands,

And wander through the woods with spring;

To them the glory of the earth

Is but to hear a bluebird sing.

They, too, receive each one his Day;

But their wise heart knows many things

Beyond the sating of desire,

Above the dignity of kings."

At the little old-time mining town of Hope we look down into the bottomless Devil's Lake, comforting ourselves with the assurance that Hope is the higher, then on to Yale. Yale is the head of steamboat navigation on the Fraser and is set in a wondrous cul-de-sac in the mountains. Passing Spuzzum we reach North Bend, where if we are wise we break the journey and enjoy a dinner to be remembered. The Fraser Canyon deserves a closer inspection than is possible through the windows of the train. The noble river forced between upstanding black rocks churns its discontent in turmoil. Near Spuzzum the Government Road parallels the railroad, and one spares a backward thought to the rugged miners of the Cariboo days whose daring and dour endurance cast into pale shadow all experiences of the Klondike gold-seekers of a day nearer by. On farther is Lytton where the Canyon opens wide to admit the great river which comes to us here held between two great lines of hill-peaks, and whose yellow mane soon discolors the clear waters of the Thompson and destroys their identity. A few miles from Lytton we cross the river on a steel cantilever and down, far down below us catch a dizzy gleam of some Chinaman washing out the discarded gold-bars of the old river. His old-ivory smile is as non-committal now as in the day when Bret Harte discovered him, and you nor no one will ever discover how much pay-dirt he gets to his pan. Fifty yards below his feet his Red brother with dip-net scoops up in struggling salmon the communal breakfast for his tepee. The Red man hates the Yellow, and the Yellow hates the Red, but both equally are fed from the beneficent bosom of the Old Mother.

Taking the train again we continue our sinuous run along the side of the Thompson, and the river and its setting give us a color-feast ranging from one end to the other of the spectrum. No Dakota Bad-Lands can rival the prismatic hues here spilt out at our feet, red of earth, olivaceous green of tree-trunk and carpeting moss, ochre-yellow of the lichen, and the purple of great bunches of wild flowers. The Dakota coloring is that of sterile desert, at our feet the tints are those of a rich and abounding life.

Then on to Ashcroft where one still runs across the pack-mules with their merchandise, their great wains and tinkly bells, for Ashcroft is the portal to the great mining country of the Cariboo and Omineca, recently revivified and brought into the world's notice by the Guggenheims. And on we press to Kamloops where the North Fork of the Thompson joins the main stream. Kamloops for you if you fear tubercular trouble. It is a good place for you, too, if you are well. This is the centre of a rapidly growing industry in irrigated fruit-lands; and away to the southward stretches a ranching and mining country right into the Nicola Valley. Eastward we are carried on the smoothest of rails to Shuswap on the western extremity of the Shuswap Lakes, dropping down to Tappen and Salmon Arm, and then still following the south shore toward Sicamous Junction and Craigellachie. The first part of this stretch is pastoral mead land; grass, growing crops, and old-fashioned hayricks are a relief to the eye almost sated with the grand set-pieces of Nature; and instinctively one's mind harks back for a moment to the Lake Country of England.

At Salmon Arm we are in the heart of the sportsman's country, to the south of us are deer, and within a day's journey to the north we find the caribou. The next station eastward from Salmon Arm is Sicamous, and a branch line to the south here will take us to Kelowna, where Lord Aberdeen has many thousand acres of apple-lands. Here is the land of oil and wine and fat things, a paradise for the fruit-grower, that "Earthly Paradise" that the poet writes of.

And now we reach Revelstoke in the foothills. If it had been our intent to go east by the Crow's Nest this is our point of divergence, but the mountains invite us, and our course is east by the main line. At Glacier we reach the first of our three great mountain playgrounds. We are eager to forget all the wise and exact and mathematical lore that we gathered at the great Coastal Exposition. "For this is no common earth, water or wood or air, but Merlin's Isle of Gramarye where you and I will fare."

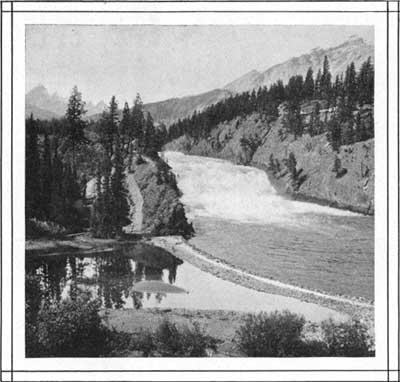

Bow Falls.

Bow Falls.

|

Sulphur Mountain.

Sulphur Mountain.

|

GLAMOUR AND THE GLACIER.

"They said the fairies tript no more,

And long ago that Pan was dead;

'Twas but that fools preferred to born

Earth's rind inch-deep for truth instead.

Pan leaps and pipes all summer long,

The fairies dance each full-mooned night,

Would we but doff our lenses strong,

And trust our wiser eyes' delight."

At Glacier we have not yet reached the Rockies, we find ourselves near the summit of the Selkirks, a range wholly different in structure to the great Rockies and separated from them by the deep valley of the Columbia. Very near Glacier House is Mt. Selwyn, the highest peak of the range, pushing up its white crest into the air a full 11,000 feet. Are you interested in mountains? You may now feed your very soul. Without being trivial we may quote Wackford Squeers, "Wot richness!" Make up your mind to rest for a week at Glacier House. You will store your being and your brain with remembrances of uplift that will neither dim nor cease to thrill while you are still, to use the phrase of the stage driver who waits for us, "above dirt." In the midst of some hot day's hard work in the after time will come like a whiff of edelweiss the remembrance of a day at Glacier photographed without your intent and scarcely with your knowledge upon "that inner eye which is the bliss of solitude."

Glacier House has been insinuated into a lateral valley of the Illecillewaet with the Great Illecillewaet Glacier and Mt. Sir Donald a glorious giant background. Both of these are easy of access. There also invites you the Asulkan Valley, with its rich woods, wondrous waterfalls and grand entourage of peak and glacier. The Valley got its name from the mountain goats which once haunted its silent solitudes.

For mountain-climbing, Mt. Sir Donald, named after the present Lord Strathcona, is the most popular peak of the Selkirks. Messrs. Sulzer and Huber made the first ascent in 1890, and next year an Englishwoman, Mrs. Berens, reached the top. Any ambitious amateur eager to explore the marvels of the ice-world can make this peak, and the climb gives experience of every variety of rock-and-ice work, the rewarding view being scenic payment in full for the sustained scramble.

Off to our left are other peaks second in grandeur only to the abrupt pyramid of Sir Donald—Macdonald, Avalanche, Uto, and Eagle; and in full view are the snowy Hermit Range and Rogers Pass. Far off in the forest the crystal line of the Illecillewaet cuts the valley. We are in a very plethora of peaks, the Rampart, the Dome, the sharp apex of Afton, and Castor and Pollox.

Three thousand six hundred feet above Glacier House on Mt. Abbott a look-out has been built directly above the mountain-torrent that throws itself down from Avalanche Peak. The summits of these hills afford coigns of vantage for the bear and the mountain-goat. Those responsible for the Glacier Hotel have shown the rare wisdom of restraint, a glacier-fed stream has been caught, and made to feed fountains in the foreground, but the simplicity and grandeur of Nature has not been spoiled by any man-made tawdry trappings. Near the Annex of the Hotel a tower has been built in which is ensconced a large telescope, which gives a wonder-sweep to all the uplifted glories of hillcrest and high glacier.

From Sir Donald's summit one may see a hundred individual glaciers. Between two giant peaks is Mt. Bonney Glacier; at the right is the Cougar Range, and away to the west the pyramid of Cheops uplifts. The great glacier could engulf in its bulk every Swiss icefield, and is the nucleus of a glacial bed covering more than 200 square miles.